Erudite Waffles (1/14/23)

Another week, another whatever the fuck this is.

What I’ve Been Up To

Well, let’s start with the bad news: a communications disaster with the copyeditor on TARDIS Eruditorum Volume 8 means that I currently have a freshly edited manuscript for the already published TARDIS Eruditorum Volume 7, no edits whatsoever on Volume 8, and a several month delay to that book. This is obviously very frustrating, and I apologize to everyone who’s looking forward to it.

Right. Onto better news. I finished reading Sandman: Book of Dreams, the 1996 short story collection co-edited by Neil Gaiman and some guy named Ed Kramer that I’ll need to Google in a second, but who I’m sure will turn out to be a perfectly upstanding gentleman whose involvement in the project doesn’t instantly derail all other conversation about it. Except, of course, the essay went out for Patrons yesterday, and you can read all about it yourself. Queuing this up on Friday morning, but I expect today will be spent looking at Storm Constantine’s Wraeththu or possibly reading some G.K. Chesterton. Or maybe REDACTED (because I want to keep that surprise for Patrons).

I approved Penn’s pencils on the next four pages of Britain a Prophecy #5, and he’s at work on inks. I also have a few annotations written for How to be an Egg in the Age of the Lilith Fair, so the odds on that happening continue to increase.

I also got some very promising news about a possible work for hire gig.

The Obligatory Rant About AI Art

I saw a tweet the other day from someone talking about how one of their regular writing gigs had informed them that their services wouldn’t be needed anymore, as the website would be using AI to write articles in the future, though they could be offered a reduced rate editing and cleaning up the AI articles. This was presented as some grave existential horror about the threat of AI, whereas I admit my reaction was “well, that website will be out of business soon.”

Which is to say that I’ve found myself very unimpressed with the discourse over AI art. Obviously the AI art utopians, with their idiot speeches about making art accessible to anyone (working class art famously taking until the 21st century to exist) can simply be fired into the sun without further comment. But I also have precious little time for the “but copyright” crowd, being as I’m a middle aged Internet grump who has been arguing against the basic idea of copyright for literally more than half my life. (Here’s Neoreaction a Basilisk on libgen, btw!)

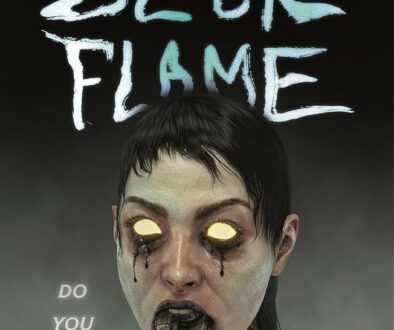

Anyway, all of this seems to me to spectacularly miss the actual problem with AI art, which is that it represents the accelerating replacement of art with content. Because the plain fact of the matter is that AI art sucks, and it sucks in ways that come down to extremely persistent hard problems in artificial intelligence that absolutely nobody has made any meaningful progress on in decades, the crux of these being that they blatantly lack any intentionality. Whereas art, on a fundamental level, requires the notion of intentionality to be art. I mean, this is an old Stanley Fish argument. Fundamentally, the breath of life that elevates a series of glyphs or an overlapping set of lines and colors into art is the knowledge that there was some entity that ordered these things into an effort to communicate. Absent that, you just have ink-smudged tree pulp.

And this is the thing that AI fundamentally cannot replicate. It might, at its best moments, create momentarily convincing illusions, but these are little more than an effective matte painting. Stare for a moment, or let your perspective shift, and the illusion crumbles. Their famous inability to handle hands as a concept is indicative, and not for the reason you might think. The problem with AI hands is not simply that they are weird bulbous masses with fingers protruding off the wrong bits; it’s that this problem makes clear that AIs do not have any real concept of what a hand is. They do not understand the context in which hands exist. More to the point, they do not understand context at all. It feels strange to stress such an elementary point in the face of both doe-eyed tech evangelists and apocalyptic doom mongers, but having a notion of context is actually very important to the creation of art.

On the one hand this sounds comforting. AI is never going to create art that matters. It might generate a pretty landscape or some generic sci-fi art, but it’s not going to write Gideon the Ninth. Human artists are and likely will continue to be able to curate AI art in interesting ways—although virtually all interesting art along those lines that I’ve seen is commenting on the fundamental failures of AI art in ways that, while clever, probably don’t actually have legs. But for the most part, if an artist’s work is capable of being done by AI, it’s an indictment of the artist. Except, of course, that marketing works, and the current age of content is making it abundantly clear that if you put enough money behind it, you don’t have to write Gideon the Ninth. You can just make an endless procession of vapid spinoffs of fifty year old sci-fi franchise that offer nothing more than masturbatory fanservice.

Ultimately I’m still not alarmist about that. In one of my few remaining beliefs that can broadly be described as optimistic, I don’t actually think art is under any long term threat from, well… anything save human extinction. Much like fucking, people are just going to keep doing it, and even reasonably competent people will remain better than AIs at it for a very long time. Moneyed interests will continue pumping addictive stupidity into the culture for as long as capitalism exists, and it will be destructive as hell, but it’s never actually going to pose a threat to art.

But that doesn’t make AI art less horrifying. And it certainly doesn’t make the people who genuinely don’t see a difference between it and actual art less so.

The Name of the Doctor Deadwoofing

Cause the opposite of a tweeter is a woofer, see? It’s a speakers pun.

This is very much part of Moffat’s “start with the volume at 11” era, but definitely shows itself at its most manic and not entirely functional—all rush and no weight.

River is specifically where it tips over out of control—the point where its reach blatantly exceeds its grasp.

Jenny getting killed is actually quite upsetting, though. Pity they have to undo it just so that, um, they can do it again later.

There’s also something legitimately to holding the Doctor back for fully 25% of the story.

The point where the Doctor breaks down in tears, on the other hand, at least clearly flags a breakdown of the rules. Better, frankly, than all the ratcheting up of scale before it.

There’s something profoundly funny about Moffat, at more or less his personal nadir writing Doctor Who, finally giving up and nicking the plot of Alien Bodies.

You can see Moffat’s most indicative tick here—the unearned ratcheting of stakes through things like “potentially the most dangerous place in the universe” and spooky rhymes that just aren’t.

This arc’s inability to decide if the Great Intelligence is actually a threat or just an absurd joke from the 60s becomes a problem here.

The jump from the Doctor and Clara talking about her memories to the villain confrontation feels like there’s episode missing.

Astonishing that Moffat could think this nothing of a use of River could end her arc.

Love the Paternoster Gang just standing there like wet noodles through the climax.

It doesn’t help the Impossible Girl arc that Clara doesn’t actually get any good scenes in its finale.

That souffle line is twaddle even for Moffat twaddle.

This episode really is just a massive amount of infrastructure to set up the reveal for Day of the Doctor, and no actual content. So much weaker than I remembered, honestly.

Although Moffat’s notion of the Doctor as performance remains one of his best character conceits. Amidst an appallingly overwritten final scene with an unearned title drop, there’s still a truly stellar concept in here. But for the most part, this is The Timeless Children done right, and still not very good.

Tumblr Ask-O-Rama

As always, my Tumblr asks are open to all, including anons.

Do you get any joy out of Randall Munroe’s ‘What If?’ blog entries? I think enjoying this kind of pure speculation is why I largely enjoyed Project Hail Mary but not Kill the Moon. I love your writing on Kill the Moon because it’s cool to see a lens through which the episode is fantastic, but I do think it (unintentionally) invites the audience to engage with it in terms of “what would the literal consequences of this choice be?” then delivers a deeply disappointing ending in that context.

The first one, with the near lightspeed baseball pitch incinerating a city, was quite fun. I remember reading the next few with a slight disappointment that they were never quite as fun as the opening salvo. And eventually, I remember feeling like I’d largely cracked the joke, which amounts to “within the vast ranges of things that can happen within theoretical physics the conditions remotely hospitable to human life are present only in a vanishingly small range.” And so every time you make something exceedingly big, exceedingly heavy, exceedingly fast, the result is massive catastrophe.

I think this ends up being a pretty good demonstration of why hard SF bores me. Because for many of the questions there’s great imaginative potential in the idea, and then the answer is just several paragraphs of being a killjoy for no reason other than to tell the same joke you told in literally dozens of other versions of being a tedious killjoy. “Billion Story Building” is perhaps most painfully indicative because it is literally a four year old coming up with a great image that you could do countless interesting stories around and being told by multiple adults why it’s impossible for extremely boring reasons like “it would fall down.”

Since you want to take this to Kill the Moon, a hill that I accept it is my fate to angrily haunt for all eternity, what I would ask is where, exactly, this invitation to think about the story in a literal way comes in. I don’t think it comes from anywhere in the story, which is too busy zooming about its concepts to every suggest that sitting down and doing math is worthwhile. So where does this instinct come from, and why would we want to pursue it given that its primary purpose appears to be shutting down the play of imagination into a kind of stultifying mantra of “but that wouldn’t work”?

A Terrible Idea

So, that thing Grant Morrison and Genesis P-Orridge have both done where they call upon the spirits of dead rock stars like Brian Jones or John Lennon and then credit songs to them, right? Alex did a variation on it with “If I Were You,” which was written by John Balance of Coil in a dream. And, obviously, all my Blake seances.

So you do an entire rock album with that basic approach. Lots of sparkling, deeply retro riffs, and you very seriously claim the songs were dictated by the bound spirits of major rock stars. But the lyrics are all just awful stuff about being trapped and bound into eternal servitude. So you have a nice jangly bit of 60s pop that sounds like a serviceable Beatles imitation, and then the lyrics are about eternal torment and cruel tyrant wizards. And you just release it, entirely straight-faced, absolutely refusing to entertain the idea that this is a joke.

Interview quote: I mean, I think it’s only natural for a writer’s interests and themes to change over time, and this is just what he’s into these days. I’ll admit, thought about redoing the lyrics to be less upsetting, but at the end of the day, who am I to rewrite John Lennon, y’know?

The Part Where She Leaves You With a Song

I’m working on Last War in Albion this week, so let’s go with a highlight off the sprawling Volume 4 playlist that I write to, The October Project’s 1993 “Bury My Lovely,” which looks and sounds more or less exactly like I imagine reading Sandman in 1993 felt.

See you Monday for, imho, one of the best LWIA sections of Volume 3.

January 14, 2023 @ 1:27 pm

I’m contemplating writing an essay on the ways in which AI Art might accidentally have shown the flaws in Deconstructivism and related critical theory. Because it created something that works like supposedly all human communication for Derrida, or its created a dead, contextless author for art for a Barthesian critic, and shown that actually, these theories do not describe art or people’s interactions with art.

We might still be able to use these theories as part of a toolbox, but AI art certainly feels like an end point of a certain set of theoretical tools by themselves.

January 23, 2023 @ 6:09 pm

The prompt was “an ordinary human hand with the normal number of fingers.”

The result reminded me of the bit late in Lucy where Scarlett Johansson demonstrates what neuro-genetic turn-on can achieve. (I don’t remember if the places I’ve said it include this one, but although Besson uses the “100% of brainpower” bullshit, the actual siddhis Lucy Miller attains, and even most of the order in which she unlocks them, call to my mind the “futique brain circuits” theorized by Timothy Leary and invoked in so much of Robert Anton Wilson’s writing.)

April 8, 2023 @ 6:39 pm

this is a late comment I realize but wrt to:

I’d be interested in a good book/essay/article/whatever on the subject of these hard problems that exist in AI. (I’d google but don’t know where to start googling, doubt I’d find useful results, and prefer the filter of a human that knows what she’s talking about.)