Gandalf’s Crap Understudy (Book Three, Part 51: Ennis’s Judge Dredd)

Previously in Last War in Albion: Judge Dredd in the late 80s and early 90s did an extensive arc concerning Mega-City One contemplating the restoration of Democratic rights. Late in that arc came another 2000 AD featured called The Dead Man, revealed in a late twist to be a secret Judge Dredd story, featuring the eponymous Judge walking the Cursed Earth aroudn Mega-City One.

“I notice bein’ Gandalf’s crap understudy doesnae stop you bein’ a condescending prick ’n’ all.” – Simon Spurrier, John Constantine: Hellblazer

At this point the main strip began depicting the backstory of how Dredd came to be a badly burnt body out in the Cursed Earth. This began with “A Letter to Judge Dredd,” a thematic sequel to “Letter From a Democrat” written in the form of a missive from a young boy questioning the efficacy of the Judge system. The boy dies horribly at the end of the strip just before his letter is delivered to Dredd, and this confluence prompts Dredd’s resignation. In an attempt to hide this fact a clone of Judge Dredd is given his badge and put on the streets in his place, which precipitated another epic, the twenty-six part Necropolis, which featured the return of the Brian Bolland co-created Judge Death. The story culminated, of course, with Dredd returning and saving the day, but still resulted in a massive death toll in Mega-City One as Judge Death and his Dark Judges spent months ruling the city. In the fallout of this, Dredd, his faith in the Judge system restored, concludes that the only way to reestablish order is to allow a referendum on the judge system and the restoration of democracy, setting up the culmination of the years-long arc.

This took place in a pair of short arcs towards the end of 1991, beginning in issue #750. The first of these, “The Devil You Know,” was penned by John Wagner and took place on the eve of the referendum, with Dredd arguing passionately against the restoration of Democracy (“When some creep’s holding a knife to your throat, who do you want to see riding up… me—or your elected representative?”) as the ordinary citizens struggle to even understand how to vote in the first place. The plot concerns a conspiracy by a group of judges to assassinate Dredd and prevent the referendum, which they (along with the rest of the city) are convinced will spell the end of the judge system.

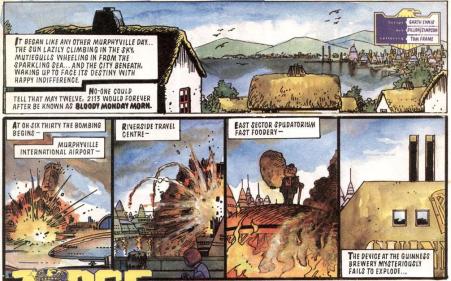

The second arc, meanwhile, depicted the referendum itself. Called “Twilight’s Last Gleaming,” it was unexpectedly written not by Wagner, who had written virtually the entirety of the Democracy arc, but rather by the incoming regular writer of the Judge Dredd feature in 2000 AD, Garth Ennis. As Ennis explains the handoff, “at that point John had enough American commitments and was writing the lion’s share of the Megazine. He had enough outside commitments that handling the Dredd strip in 2000 was too much work.” And so the opportunity passed to Ennis, who was of the up and comers the one with the deepest affection for Dredd, and, with his clear love of transgressive and boyish humor, one of the two most obvious fits for the property. (The other would get his turn soon enough.)

Ennis landed the beast that was the Democracy arc with aplomb, although by and large it was a foregone conclusion—the strip would end if the referendum passed, after all, and Wagner had clearly sown the seeds for why it would fail. In many ways his first story showed the techniques that had served him on Hellblazer. The bulk of the first story is taken up by narration, although Ennis, yielding to Dredd’s fundamental remoteness as a character, opts for third person limited perspective narration instead of the first person he used in Dangerous Habits. But the underlying noir influence shone through. “From that high up the city looked beautiful, like a huge jewel on the east coast—sun dancing on the glasseen towers, the Mega-Ways criss-crossing in a blur of movement, and a muted neon glow winking from the constant twilight of the lowest levels. He couldn’t see the cancer from that distance, the bloated evil rot that touched everyone below and cut a flaw in the jewel like a gangrenous wound. But Dredd looked out over the city—his city—and he knew. ‘Mega-City One… eight hundred million people and everyone of them a potential criminal. The most violent, evil city on Earth… but God help me, I love it.’”

Ultimately, the overwhelming majority of voters fail to vote at all; many of those who do spoil their ballots. Of the remainder, only nine percent voted for democracy, with the Judge system surviving by an overwhelming margin. This leads to an immediate march by the democrats, who assume the result is a fix, climaxing in a faceoff between Dredd and Dupre, one of the activists from way back in “Revolution,” in which Dredd hands over his gun and approaches the march alone and unarmed, declaring that he can “kill any last thoughts of democracy ten times as dead as an assault unit could.” There he calmly explains why the referendum failed: “Democracy’s not for the people—not because we say so, but because they don’t want it.” And so a broken Dupre is left to tearfully tell Dredd, “You are the law,” and John Wagner’s greatest and most incisive Judge Dredd arc came to a conclusion at the hands of another man.

Ennis’s run on Judge Dredd, structurally speaking, is much like those that came before, in that it is dominated by short one-off pieces, many broadly parodic. An early and indicative piece was “Emerald Isle,” a six-parter with Steve Dillon that saw Dredd sent to Ireland. It’s a witty satire, taking aim at the idea of Ireland descending into a self-parody for the sake of pleasing tourists while also having some commentary on the Troubles, but there’s a strange lack of discipline to it—it comes off as a formless list of satirical points rather than a story. Considering that he was doing the immaculately tight and well-constructed Dangerous Habits at the same time, this is a surprising failure mode indeed.

Other satires offered a sort of gormless light comedy. Ennis did several in the old “parody a piece of pop culture” mould—“Twin Blocks,” for instance, was a parody of Twin Peaks, but it was ultimately only able to get at some of the most superficial trappings of David Lynch and Mark Frost’s surrealist masterpiece: “damn fine coffee,” the “Mop Lady,” and the overly flirtatious Tawdrey Thorne all make appearances, but nowhere can Ennis even begin to approach the bizarre dream sequences and haunting supernatural touches that defined the show. “Teddy Choppermitz,” his take on Tim Burton’s Edward Scissorhands, does somewhat better by at least finding room to laugh at the underlying silliness of the premise, but by and large these are little nothings that feel as though they were dashed out in a hurry.

Certainly Ennis has little good to say about his Judge Dredd run, declaring, “I would say about 10% of them are good. Some others – bits of stories are good. And a lot of it’s rap, to be quite honest with you.” He cites a few stories—including “Teddy Choppermitz”—as ones he likes, particularly “A Man Called Greener,” about a competitive spitting tournament gone badly wrong, which Ennis identifies as “capturing that insane feeling that all the great Dredds had. The ones from 1980 to 1986.” He names a few others here and there, including his opening arc “Death Aid,” but it’s clear that by and large Ennis considers his Judge Dredd run a failure.

Ennis proposes a number of reasons for this inadequacy. He bluntly cites, for instance, the “bad editing at the time. The comic was in the hands of Richard Burton and Alan McKenzie who were not up to the job,” further describing how “He made a number of bd decisions, a number of decisions that I just frankly did not understand, alienated a lot of people, and seemed to be more interested in establishing his own position of power than in editing a good comic… He never liked the idea of writers and artists communicating. He didn’t have the aptitude for that kind of authority.” But the larger failure, as Ennis sees it, was him. To some extent Ennis is, ironically, unconvincing on this point—his claim that he was “too young, just not ready for that level of work. I was writing all sorts of stuff as well as Dredd and still trying to write a weekly strip. I just wasn’t up to it, I wasn’t ready” is hard to credit given that he was simultaneously establishing himself as a standout talent within a generation of standout talents over at DC. But he is much sounder on his larger point, when he notes that “ I can’t do Dredd right because I’m too close to it, too reverential. I like it too much. The instinct that allows me to go in and piss all over American superheroes and end up writing quite entertaining stories about them – where Batman and Green Lantern turn up in Hitman and are thoroughly pilloried or where Wolverine and Spiderman and Daredevil appear in Punisher and have a terrible time – that instinct to go in and tear characters apart and come up with entertaining if controversial stories, that just isn’t there for me when it comes to Dredd.”

This tendency to be overly reverential is perhaps clearest in Judgment Day, Ennis’s take on the extended epic in the vein of The Cursed Earth or The Apocalypse War. Spanning both 2000 AD and the Megazine, this was a massive story that saw a powerful magus raise an army of zombies to try to destroy the world, with Mega-City One particularly affected because of the massive number of dead from Necropolis buried just outside the city. The story is certainly not bad—it’s got Judge Dredd versus an army of zombies, after all, and further spices things up by having him team up with Johnny Alpha, the lead character of Strontium Dog, another one of 2000 AD’s most popular features. (Alpha had died two years earlier, but time travel allowed Ennis to use him anyway.) With so much thunder it would have been difficult for a writer of Ennis’s basic skill to turn in an actively bad story. But equally, it’s difficult to argue with Ennis’s critique that “ I recycled too much material that had appeared in other epics. There’s bite of Apocalypse War all over that story,” although he’s right that the final page, which sees Dredd and Alpha saunter off to cross the desert with Dredd confidently noting, “who the hell’s gonna mess with us?” is a fun beat.

Ennis’s Judge Dredd run has its highlights, to be sure—a smattering of short stories in which he applies his noir-influenced sensibilities to the satirical setting to create something appreciably new. “A Rough Guide to Suicide,” in Prog 761, sees the proliferation of an eponymously titled pirate video that encourages and offers a guide to committing suicide. This sparks a wave of suicides (“the latest craze,” Dredd grimly notes), overwhelming the Judges. And so they set out to arrest the writer of the video and force him to denounce his work, only to find him hanging in his closet with a note declaring that “An author should always have the courage of his own convictions. Besides, I’ve been feeling a bit depressed lately.” As Dredd and Judge Hershey watch a roof jumper sail past the window, Dredd grimily notes that “it’s gonna be a long night,” and the story ends with oblique and effective nihilism.

Another piece, “Last Night Out,” towards the end of Ennis’s run, sees him hone the style with a piece about Judge Cahill, a veteran judge with cancer from a zombie bite who, with six hours left to live, goes on a last patrol with Dredd, is similarly bleak, this time taking a more directly noir style, an approach Ennis had previously honed on the five-part “Raider,” which saw Dredd confront a vigilante ex-judge. “Unwelcome Guests,” published a few weeks later, offers a flatly nihilistic take on PTSD, violence, and police abuse that gives a real sense that Ennis was, late in his run, starting to figure out a clear voice to use on Judge Dredd—one that favored eliptical amorality plays that lingered uncomfortably in the satire and fascism of the strip. And it’s notable that his beloved “A Man Called Greener” came from this late period as well. It took a more juvenile approach to be sure, but it had a similar elipticism and inclination to go for an unsettled lack of resolution.

Equally, many of Ennis’s other strips in this period were still tired and lifeless. He flickered into form here and there, yes, but it would be a dramatic overstatement to say that the tail end of his run was good. Perhaps he would have further evolved and grown. Perhaps, as he suggests, nobody but John Wagner can actually write a decent Judge Dredd story. Ultimately it’s impossible to tell; Ennis, for his part, frustrated by the bad editorial decisions and concluding both that “I was always goign to be much happier writing my own characters, doing my own material” and that “the treatment of creators in American comics was at that time so much better. In terms of the relationship you have with the editorial staff, the way you’re rewarded financially for your work. Really, they’re streets ahead. The situation at Marvel and DC isn’t ideal, it’s still on an editorial level streets ahead of how things were on 2000 AD – at least, when I was there.” Ennis’s last Judge Dredd came in Prog 839, in the June of 1993, and by this time he was already alternating stories with his replacement, Mark Millar. And just three issues later, with Prog 842, 2000 AD would begin one of its strangest ever experiments: the Summer Offensive. [continued on July 25th]