Glassy-Assed Jokers (The Last War in Albion Part 12: Roscoe Moscow, The Underground)

This is the second of seven installments of Chapter Three of The Last War in Albion, covering Alan Moore’s work for Sounds Magazine (Roscoe Moscow and The Stars My Degradation) and his comic stripMaxwell the Magic Cat. An omnibus of the entire chapter, sans images, is available in ebook form fromAmazon, Amazon UK, and Smashwords. It is equivalently priced at all stores because Amazon turns out to have rules about selling things cheaper anywhere but there, so I had to give in and just price it at $2.99. Sorry about that. In any case, your support of this project helps make it possible, so if you are enjoying it, please consider buying a copy.

PREVIOUSLY IN THE LAST WAR IN ALBION: Alan Moore began his professional comics career in the pages of Sounds under the nom de plume “Curt Vile,” debuting Roscoe Moscow: Who Killed Rock ‘n Roll.

“Hawdy haw! You glassy-assed jokers are a pushover!” – Alan Moore, Astounding Weird Penises

Much of this is due to the nature of Sounds as a magazine. It is, of course, primarily a music magazine, which means that its comics section was largely an afterthought. It was also, in many ways, the third rate music magazine of the late 1970s. The big two magazines were NME – the New Musical Express, to which Moore made his first professional sale: a drawing of Elvis Costello – and Melody Maker. These magazines were not meaningfully competitors – both were published by IPC, publishers of 2000 A.D., and presented a reasonable dichotomy. Those with traditional and more conservative taste could go to Melody Maker, edited by Ray Coleman, which was still embracing prog rock while getting very excited about Bruce Springsteen. Those favoring a more progressive, avant garde approach had NME, which was openly political and had a bevy of music writers who went on to become the sorts of elder statesmen that The Guardian likes to hire.

|

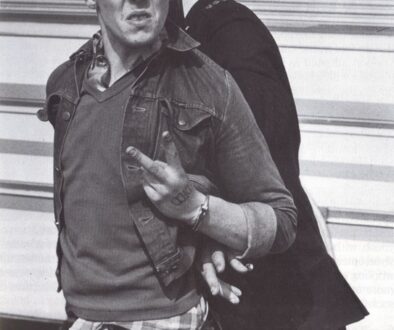

| Figure 91: Nicky Crane on the cover of Strength Through Oi! |

So when Jack Hutton and Peter Wilkinson left Melody Maker in 1970 to start their own company, this was the closed system they confronted. The approach they eventually settled on was straightforward: they were the magazine that would embrace brash, new music. Sounds was the first of the three music magazines to embrace punk, and eventually spun off a heavy metal magazine called Kerrang! that, unlike Sounds, continues to be published today. Sounds was originally conceived of as a left-wing magazine, but by the late 1970s had become something of a mishmash – Sounds covered the Oi! subgenre of punk extensively, to the point of, in 1981, releasing a compilation called Strength Through Oi!, a subversion of the slogan “strength through joy,” the cover of which featured gay neo-Nazi Nicky Crane on the cover. Crane was, at the time, serving a prison sentence for having violently attacked more black people than was socially acceptable. (Sounds and the album’s compiler, writer Garry Bushell, insisted that this was just a misunderstanding, and that they were unaware of the identity of the skinhead chosen for the cover. The incident was not, in any case, sufficient to drive the usually reliably leftist Moore away from the magazine – he kept working for Sounds for two years after Strength Through Oi!.)

On the other hand, Sounds still had enough of a leftist following that, in the May 3rd, 1980 issue it ran a letter from reader Derek Hitchcock savaging Roscoe Moscow for being “insulting to anyone with a minimum of intelligence because of their cheapness and because of their blatant mocking prisoner,” specifically calling the strip out for a series of jokes in the 50th installment in which Moore bemoans being trapped “down a sewer with a hommerseckshul space-monster,” complete with crude puns about being “willing to bend over backwards in order to help you.” Moore responded two issues later with characteristic vehemence, pointing out that Moscow is “not meant to be a very nice character. He’s terrified of women, he’s terrified of homosexuals, he has a deep and xenophobic loathing of foreigners, he’s a card carrying Republican who campaigned for Nixon, he’s an alcoholic, sexually inadequate neurotic who can’t hold down a job and dresses up like a private eye as part of a pathetic attempt at self-respect,” and blasts Hitchcock for his “arse-backwards conclusions delivered in a more-liberal-than-thou tone of righteous indignation,” while, equally characteristic of Moore, self-deprecatingly disclaiming that he was “not claiming that Roscoe Moscow is a good comic strip, or even a mildly funny one.”

|

| Figure 92: Roscoe Moscow is institutionalized shortly after Derek Hitchcock’s complaints (Alan Moore, 1980, as Curt Vile) |

For all Moore’s adamance that he had enough respect for the readership of Sounds not to run a disclaimer to this effect, it is perhaps telling that he wound down the strip soon after, replacing it with the sci-fi themed The Stars My Degradation. Perhaps more telling than the mere fact that he ended it, however, is the emphatic anger with which he did. Not long after his exchange with Hitchcock, Moore has Roscoe Moscow suffer a complete nervous breakdown and be carted away to an asylum, where he’s shown as a broken figure, restrained in a straitjacket and drooling helplessly on himself. The final strip features a flash forward of Roscoe Moscow’s rehabilitation into the stifling banality of an ordinary life working at the chicken fat canning company juxtaposed with photos of Alan Moore telling a lame joke to enliven a strip he admits is “not that funny… I mean, none of them have been that funny, but this one’s really grim.” It’s difficult to escape the sense that Moore is on the one hand trying to conclusively demonstrate how wrong Hitchcock is, and on the other suddenly finding the strip just as unpleasant as its detractors did.

That Moore’s strip should get caught in accusations of right-wing bigotry is not only fitting given the later travails of Sounds, it is fitting given the obvious influences on Moore’s work for them. For all that Roscoe Moscow delighted in its stylistic imitations of other material, its basic style was drawn from the underground comix scene – a scene with its own complex history of being accused of bigotry.

|

| Figure 93: Gershon Legman described the “horror-squinky” tendency in American comics as early as 1940. |

The figure most associated with the underground comix scene is Robert Crumb, often credited simply as R. Crumb, and the movement is generally treated to have started with his publication of Zap Comix #1 in 1968. As with most things, the truth is more complicated. Zap was certainly revelatory, and its brand of confessionalism and obscenity filtered through the meticulous draftsmanship of R. Crumb. So central is Crumb’s artistic abilities and style to Zap’s success that it is not difficult to see why he’s treated as the visionary founder of the style. On the one hand, Crumb is an immaculately talented artist who combines expressive naturalism with a fluid, cartoonish elasticity that lets him move seamlessly from the intensely human to the perversely grotesque. Combined with the iconoclastic obscenity that was perfectly in step with the times in 1968, putting Crumb at the crest of the same wave that had J.G. Ballard writing “Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan” in the same year. In many ways it was a matter of being in the right place in the right time; Zap was published in San Francisco in the autumn of 1968, while it was still at the forefront of hippy culture.

In practice its publication owed much to the countercultural infrastructure already in place from San Francisco’s embrace of the Beat scene a decade earlier. Zap was printed by Apex Novelties, owned by Don Donahue, who got Beat poet Charles Plymell to print the comic by giving him his hi-fi tape player. It was thoroughly enmeshed in the hippy scene – Zap was preceded by Crumb’s work in a paper called Yarrowstalks, which Crumb describes as “corny hippy spiritual stuff,” and the shift between Zap and Crumb credits the transformation between his late 60s work and his earlier works to his taking LSD in 1966.

But Zap isn’t even the point where these countercultural movements and comics intersected for the first time. Crumb got his start in comics on Harvey Kurtzman’s Help in 1964. Kurtzman, for his part, pioneered a satirical style of comedy in the 1950s with a particular focus on ornate sight gags via MAD, which he oversaw for the first several years of its publication. MAD lacked the over the top obscenity of Crumb’s work (which is for the best – its publisher, William Gaines’s EC, had enough problems and was made the scapegoat for a moral panic in the American comics industry following the 1954 publication of Fredric Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent), but it shared the madcap sensibility and aesthetic of the grotesque. Certainly MAD’s basic format of satirical parodies of pop culture subjects is a visible inspiration for Roscoe Moscow.

|

| Figure 95: Alan Moore’s S. Clay Wilson homage (Alan Moore, 1979, as Curt Vile) |

Although the first issue of Zap consisted entirely of Crumb’s work, by the time of Zap #2 Crumb was accompanied by other cartoonists in the same spirit. Of particular note in Zap #2 was the debut of the scenes second leading light, S. Clay Wilson. Crumb describes his initial impression of Wilson’s work as “something I’d never seen before, anywhere, the level of mayhem, violence, dismemberment, naked women, loose body parts, huge, obscene sex organs, a nightmare vision of hell-on-earth never so graphically illustrated before in the history of art,” going on to admit that “suddenly my own work seemed insipid.” Crumb was not to be outdone, and his own work became increasingly more viscerally depraved in accordance. Wilson’s style favored intricate tableaus of demons engaged in staggeringly depraved acts of sex and violence, and was the subject of a direct homage within Roscoe Moscow.

|

| Figure 96: Art Spiegelman’s Ace Hole: Midget Detective was an explicit influence on Roscoe Moscow |

But the underground artist most straightforwardly linked to Roscoe Moscow was Art Spiegelman, whose collection of the first few installments of Maus is typically grouped with Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns and Moore and Dave Gibbons’s Watchmen in arguing for the idea that 1986 was the annus mirabilis of comics. Spiegelman’s story “Ace Hole: Midget Detective” is a straightforward and admitted inspiration for Roscoe Moscow. Like Roscoe, Ace was a Mickey Spillane-style noir investigator who winds his way through a formulaic narrative decorated, not by the deformed detritus of the music industry, but by the world of modern art, particularly the work of Pablo Picasso.

That a single movement should incorporate both the aggressive obscenity of S. Clay Wilson and the literate erudition of Art Spiegelman demonstrates that the scene had considerable breadth. Indeed, for all that it’s associated with San Francisco, the underground movement at large had far broader reach. In the UK, at least, the vanguards of this were the counterculture publications Oz and the International Times. Oz, in particular, pushed the underground scene, launching Cozmic Comics in 1972 to reprint classic American underground work alongside British comics. Cozmic Comics provided early bylines for artists like Brian Bolland and Bryan Talbot. (Moore, in fact, enthused about working with Talbot on an aborted serial for Warrior because Talbot’s “background is as solidly rooted in the underground” as Moore’s.) Indeed, it was the cover of Oz #18 that provided Moore his first glimpse of Crumb’s work in the form of an illustration of Crumb’s recurring Angelfood McSpade character.

But Moore’s most sustained engagement with Crumb came in the form of Arcade, a late entry in the underground comix scene. By the time of its 1975 debut the countercultural claims of the underground were firmly on the retreat. Between the 1973 Miller v. California Supreme Court ruling that allowed local communities to set their own standards for obscenity and a crackdown on the head shops in which underground comix were distributed, the distribution networks that had allowed the comics to thrive were withering. Meanwhile, the mainstream was already starting to recuperate the subversive energy of the underground. Marvel, in 1974, launched Comix Book, which featured artists like Art Spiegelman and S. Clay Wilson doing anodyne iterations of their usual work. Comix Book floundered, but in 1976 Marvel tried again with Howard the Duck, which featured Steve Gerber and (after a few issues) Gene Colan doing funny animal satire in a decidedly post-underground vein.

|

| Figure 98: Bill Griffith’s Zippy the Pinhead continues to be syndicated in newspapers today. |

Arcade, spearheaded by Art Spiegelman and Bill Griffiths, was, as Crumb put it, “an attempt to pull together the rapidly disintegrating ‘underground movement.’” This sense of decline in the movement was explicitly shared by Spiegelman, who said that in the 70s “what had seemed like a revolution simply deflated into a lifestyle. Underground comics were stereotyped as dealing only with Sex, Dope and Cheap Thrills. They got stuffed back into the closet, along with bong pipes and love beads, as Things Started To Get Uglier.” Arcade, then, was his effort to move past that. It’s important to note that both Spiegelman and Griffiths had careers that went beyond the underground. Spiegelman, on the back of Maus, transformed himself into an icon of literary respectability, while Griffiths transitioned from the underground to a widely syndicated newspaper strip, taking his Zippy the Pinhead character from the pages of underground publications like Real Pulp Comix to King Features Syndicates, who send daily installments to mainstream newspapers alongside pinnacles of counterculutral subversion like Blondie, Rex Morgan M.D., and Family Circus.

Arcade, in other words, was an ambitious publication.As Moore put it in his appreciation of the magazine, “Too Avant Garde for the Mafia” (the title comes from Griffiths’s reply to a letter Moore sent the magazine), “Arcade served as a rallying point for those cartoonists who were more concerned with their art than their bank balances,” although in the case of both Griffiths and Spiegelman (and for that matter Moore), it’s perhaps more accurate to say that they were concerned with the idea that the two might be interrelated. [continued]

October 3, 2013 @ 7:15 am

What, no comments? Not even about Moore's Oz #18 cover?

October 3, 2013 @ 7:20 am

“Arcade served as a rallying point for those cartoonists who were more concerned with their art than their bank balances,” although in the case of both Griffiths and Spiegelman (and for that matter Moore), it’s perhaps more accurate to say that they were concerned with the idea that the two might be interrelated.

Or, to put it another way: "By necessity we must be self supporting. Popular media are bigger than fine art media. Aesthetic mediums must infiltrate popular mediums." (Gary Panter, item 10 of THE ROZZ TOX MANIFESTO)

October 3, 2013 @ 8:05 am

I hope my lack of comment doesn't suggest lack of interest. I'm loving Last War in Albion and am blown away by the amount of research and detail Phil is including; for example his two or three paragraphs detailing the baroque history of the UK music weeklies suggested a man who, like me, in the 1970s ran to the newsagent every wednesday for his weekly fix of anarchic muso gossip, tour news and scandalous lies rather than the contemporary young American phd and Doctor Who nerd we know and love . By the way the 'comic strip section' of the 'inkies'* hardly took up an eighth of one page (usually under the letters column), it was hardly the Sunday funnies, so for Moore to get any kind of gig in that tiny space is impressive.

*So called because of the cheap newsprint which left one's hands as black as a coal miner's after few minutes reading.

October 3, 2013 @ 8:32 am

Bill Griffith doesn't get enough credit for introducing the underground to the "straight" world. I recall when the Hartford Courant started carrying "Zippy" around 1985: they would run days' worth of letters of complaint, about it being weird, unfunny, creepy, etc. and the strip really bothered me at first, too, but then something clicked and I began to love it—so I dug around to find out about Griffith and that led to Crumb and Spiegelman.

October 3, 2013 @ 10:18 am

Yup, reading and learning at this point — don't have much to say.

October 3, 2013 @ 10:19 am

To be fair, I spent four days trying to figure out what the hell to say about that cover. (Next post I get to Crumb and race.)

October 3, 2013 @ 11:28 am

I remember reading Zippy as a kid when the Washington Post printed it. Definite anomalous, when Berke Breathed is about the most subversive person you've read. Which is a very interesting thing, looking at something as overtly weird as Ziggy as someone who's totally unaware of the cultural space it came from, when for me (generationally at least) the 70s counterculture is something typically experienced in a historical or archival frame.

Hell, might be related to my political differences from what seems to be the most common position among commenters here (leftism via subversion, postmodern liberalism, etc.) The other day a professor and I had a discussion about how many people born between the mid-80s and now haven't really seen the possibility of reforming or transcending capitalism as we know it. Most of the achievements of the 60s and 70s were rolled back or torn down before we can remember (and even the basic stuff laid down in the New Deal etc. is tenuous). So where my professor stopped waiting for the revolution, I've stopped waiting for meaningful reform.

October 3, 2013 @ 4:39 pm

Have your talents for redemptive readings finally hit a wall? 🙂

October 3, 2013 @ 4:39 pm

Hey, my captcha was singeek!

October 4, 2013 @ 1:51 pm

Thank you. In truth those paragraphs were the product of me asking Andrew Hickey for a primer, and then adding a bit of Wikipedia research. So I'm heartened to know the illusion held. 🙂

October 4, 2013 @ 1:52 pm

No, actually – the redemptive reading is easy. Alan Moore makes it himself. I'm just not sold, and more to the point, am kind of flummoxed that Moore is, since it's so unlike him.

April 12, 2016 @ 7:34 pm

Yeah, once again having actually lived and grown up within the culture under anthropological scrutiny, I don’t really recognise certain aspects of the stuff which is stated herein with such apparent confidence. Sounds was neither particularly rightist nor ‘leftist’ but was principally a metal/rock publication (and as such conservative with a small c) with a few oddballs who managed to keep it interesting, mainly Bushell (albeit for the wrong reasons, excuses made for the 4Skins at Southall etc.), Daves McCullough and Henderson who covered all the sort of left-field stuff that the shitty NME wouldn’t have touched with a barge pole, NWW, DIY tapes, Some Bizarre etc. Sorry – NME was always wank at the best of times, and the suggestion of Sounds as something which wasn’t quite as good may make for a nice pattern but doesn’t really reflect anything of the time under examination. See also Blue Peter in something else you wrote. Sorry – but it really was chess club shite. Most of us watched it because there wasn’t anything else on and so we could join in with the piss-taking at school next day.