Homecoming

You know, before you start reading this, I have a favor to ask. Go get a glass of water before you settle in. If you haven’t already? It can be cold or warm, with ice or bubbles or neat. Place it anywhere within arm’s reach — next to your keyboard, or on the coffee table, even in your lap if you want. But it has to be water – not coffee, not beer, not a soda. Just water.

You know, before you start reading this, I have a favor to ask. Go get a glass of water before you settle in. If you haven’t already? It can be cold or warm, with ice or bubbles or neat. Place it anywhere within arm’s reach — next to your keyboard, or on the coffee table, even in your lap if you want. But it has to be water – not coffee, not beer, not a soda. Just water.

I mean it. I’m serious. Go ahead, I’ll wait.

Thank you. You know who you are.

Bridge

Let’s start with something that might seem very subtle at first, and yet upon reflection is blatantly obvious – the Bridge. The very first scene of The_OA begins on a bridge, where we see OA jump off the side. She’s not to trying to kill herself, she later says; rather, she’s trying to go back and find Homer, someone she left behind. This is apparently to be accomplished by falling into the Mississippi River.

This jump off a bridge is bookended by the great scene at the end of “Homecoming,” where a van full of children catapults off the side of another bridge and plunges into icy waters. It’s here that OA, known as Nina at that point in her life, has her first Near Death Experience. Where she has an experience of The Other Side.

So of course The Bridge is a symbol, or a metaphor, for “crossing over” from the realm of the living to the realm of those who’ve passed on. This makes sense. Bridges are liminal spaces – they are the place “in between” two different distinct places that are otherwise separated by an impassible boundary which we traverse – like a gorge, or a river, or a channel, often at a great height. But no one really spends time on the bridge itself – it’s a means to an end, not a destination in of itself, generally speaking. (Nor do we usually consider the waters rushing below as being a destination – that’s generally what we’re trying to avoid in the first place, but we’ll get to that.)

The conversations that take place on the bridges, by the way, are rather telling of The_OA‘s sensibilities. In the opening scene, a boy is recording on his phone, through which we see OA run across the bridge, practically bouncing off the cars.

BOY: Mom, Mom! That lady—

MOM: She’s fine. See? She’s okay.

OA cuts across the oncoming traffic to the side of the bridge.

BOY: She’s going to the other side.

MOM: No, no—don’t! Oh God—Don’t look!

BOY: She let go.

And she falls. Which is very surprising, of course, but it should make at least basic sense now to anyone who’s seen the whole series. So let’s pay attention to the conversation instead, because that is something that I believe has been overlooked.

Two distinctly different experiences are occurring here. First, there’s the Mother, who doesn’t want to pay attention at first, she’s trying to ignore what she probably thinks is a homeless person. Mother is a bit anesthetized, perhaps willfully, and this is how a lot of people in the show are depicted. (Funny, she uses the word “See?” as a gloss.) Even when OA jumps, and Mother can’t help but watch, her instinct is still to teach her boy to not look… to not see. She’s in a position of power, of authority over him, and when confronted with something beyond her ken—of course she doesn’t want to face it.

The Boy, on the other hand, has rather poignant lines. He’s the one to point out that there’s a woman running in traffic; he still cares. He can still see, he isn’t blind, willfully or otherwise. But the next line, wow, “She’s going to the other side,” I love it. Because yes, she’s going to the other side of the bridge, but considering that “The Oher Side” has completely different connotations, it’s worth considering, even this early in show, given the climax of this chapter.

Now, I’m not advocating jumping off bridges. Rather, this is a metaphor—specifically, a metaphor for what some might call a “spiritual” practice, or even “The Great Work,” and the point of all this work is “ego death,” which is tantamout to “letting go.” This has the power to confer an experience of oneness with the Universe, of communion and connection with others and the world around us. Again, the Boy points this out, however obliquely: “She let go.”

Let’s compare to the other bridge scene—Nina is riding along with a strong sense of dread, the eggs in her belly feeling stuck and unbroken, and then one of the other girls breaks into this reverie with a most peculiar conversation about some show or movie they just saw:

Let’s compare to the other bridge scene—Nina is riding along with a strong sense of dread, the eggs in her belly feeling stuck and unbroken, and then one of the other girls breaks into this reverie with a most peculiar conversation about some show or movie they just saw:

GIRL: Yeah, but I didn’t like it. It made you think too much about death.

BOY: Like when the boy shoots himself.

GIRL: Yeah, like one day you are here, and then suddenly you aren’t here. You aren’t anywhere. Did you see it, Ninny?

NINA: I think you are always somewhere.

GIRL: What’s wrong with your nose?

NINA: Oh, it’s nothing.

And then all hell breaks loose, as an explosion on the bridge sends the van careening off the side, sending all of its occupants to a watery grave.

Unlike the opening scene, the conversation here is kind of on the nose (heh); it’s not subtle at all. They’re talking about death, and then there’s an experience of death. Nina says you’re always somewhere, and sure enough she has an experience of “somewhere” when she dies. But there’s an important difference between this bridge scene and the first – the first bridge scene is “recorded” by passers-by in a car on a smart phone, while the second one is narrated by OA herself, and is presumably being “imagined” by the people sitting in attendance, or, more likely, herself. The POV here what we’d call “third person limited,” it’s presumably limited to what OA knows and really what she’s saying to the five people she’s gathered around her. So we have to ask, and we might as well given this is an issue we’ll be returning to again and again… is the on-the-nose dialogue possibly being supplied by OA? Is the narration itself unreliable? And if so, what kind of unreliability are we talking about? Are the scenes we’re seeing representative of what the Five are imagining, or what OA is imagining as she tells the story? We’ll have to wait and see. I mean, it’s not that much different than the opening scene, but the references there are a bit more oblique. Still, this could all simply be an aesthetic of the show. (Well, it is an aesthetic of the show, which has other consequences we’ll cover in later entries.)

Speaking of on-the-nose, there’s the matter of the nosebleeds that Nina has upon waking from her prophetic dreams, and the nosebleed she has just before her dreams came true. Some have said this has a Stranger Things sort of vibe to it, but to me it very much invokes LOST, where our heroes who’ve had a bit too much time-travel start having nosebleeds before they die. We’ll go back to LOST and nosebleeds (and other bleeding, for that matter) when it’s time. For now, though, it should be pretty clear that just from these Bridge pieces that there’s a connection to death, both mundane and esoteric. Which becomes abundantly clear in Nina’s near-death experience.

The Big House

The Big House

Nina’s curled up in the fetal position, in periwinkle-blue water (I remember that color!) when a mysterious woman in tattered red robes reaches out her hand and pulls Nina up, now fully awake and dry. The Woman in Red is definitely not Nina’s mother; she looks completely different from the picture on the wall in Nina’s house, and she speaks Arabic, not Russian.

The woman’s name is Khatun, an interesting name. It means “queen regnant” or “empress,” referring generally to the wife of “the ruler” within the Turkish Khaganate of the Mongol Empire, but suggestive of having actual dominance or power. In modern usage in languages like Urdu, it simply means “woman.” But the context here is everything – in what is presumably the Afterlife, the “wife of the ruler” would be The Goddess, which is a rather striking departure from the Abrahamic religions. So I find this all very appealing. The etymology of the word appears to come from the Persian elements of “kata” and “bânu” – the latter means “wife” but the former can mean either “king, lord” or “house, city” – and Khatun sure looks like the queen of the Big House that comprises the “somewhere” of Nina’s near-death experience.

As mentioned before, Khatun’s robes are predominantly red, which in Alchemy suggests the final rubedo stage of The Great Work; Khatun is thus someone with advanced spiritual knowledge. The other notable aspect of her visage, though, is that she has braille on her face. The braille is apparently in German, and includes words like “hints” and “angel” though it’s hard to be sure. More telling, however, is that Nina isn’t blind yet, though she soon will be, suggesting either that Khatun already knows what will happen, that she has future knowledge… or, OA has already back-filled this information into her telling of the story, using her own future knowledge.

So, about this place – I’m calling it The Big House. Not a phrase that derives particularly from NDE literature, just my own personal shorthand. We see what looks like floating lights, perhaps pollen or stars or galaxies against a deep black background, but we also see them through a myriad of “panels” or walls, clear and yet reflective,  suggesting a mansion that goes on forever (or a certain Library for that matter). And this suggestion of a “big house” is buttressed by other “house” images in the chapter – the Dollhouse, for example, in OA’s childhood room with the Johnsons, which she uses in her video cry for help. They appear in Nina’s childhood – “The snow was seven feet high, but you could still make out many big houses behind the big gates lost in the white.” Nina actually grew up in a “big lonely house.” And, then, of course, there’s the “abandoned house” in which this storytelling takes place.

suggesting a mansion that goes on forever (or a certain Library for that matter). And this suggestion of a “big house” is buttressed by other “house” images in the chapter – the Dollhouse, for example, in OA’s childhood room with the Johnsons, which she uses in her video cry for help. They appear in Nina’s childhood – “The snow was seven feet high, but you could still make out many big houses behind the big gates lost in the white.” Nina actually grew up in a “big lonely house.” And, then, of course, there’s the “abandoned house” in which this storytelling takes place.

With such repetition (especially in juxtaposition to the emphasis on “home” in this episode as well, and don’t worry, imma take you there) I think we’re encouraged to consider the “house” as a metaphor or at least having some symbolic value. The big lonely house Nina grew up in with her father is reflective of their psychology – they are kept apart from the rest of society (I’ll return to this again in the next essay) as the nouveau rich, living in a “secret enclave” outside of Moscow. And lonely, because the mother died in childbirth (another metaphor that may resonate later). The abandoned house, on the other hand, is unfinished, much like the people OA has gathered to hear her tale, and perhaps even reflective of OA herself, whose work is unfinished. She tells the story on the top floor, the attic perhaps, the place where dreams occur, where we imagine.

This is also related to OA’s command that the people listening to her story in the unfinished house leave their front doors open. Your house is a metaphor for you – by ritualizing the front door open, one has proved to the subconscious that one believes, or at the very least that one trusts, this woman. It’s a common phrase, “leaving the door open” for future possibilities; here it is literalized as ritual because it’s very easy to say we’ll be open minded about something all while not being open minded about it at all… but enacted ritual, that gets processed by the subconscious regardless of conscious beliefs.

“Now my aim is clear: I must show that the house is one of the greatest powers of integration for the thoughts, memories and dreams of mankind. The binding principle in the integration is the daydream. Past, present and future give the house different dynamisms, which often interfere, at times opposing, at others, stimulating one another. In the life of man, the house thrusts aside contingencies, its councils of continuity are unceasing. Without it, man would be a dispersed being. It maintains him through the storms of the heavens and through those of life. It is a body and soul. It is the human being’s first world.”

— Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

One is tempted to say that a House has a psychogeography to it.

So the Big House of the near-death experience is also reflective of the psychology of that experience. As such, I would hesitate to consider it literally. However, just because something isn’t literally true doesn’t mean it isn’t true – for when it comes to matters of the Divine, or the invisible self for that matter, we have to learn to see beyond appearances to grasp what truly matters. Literalism, as such, is so very limited as an approach.

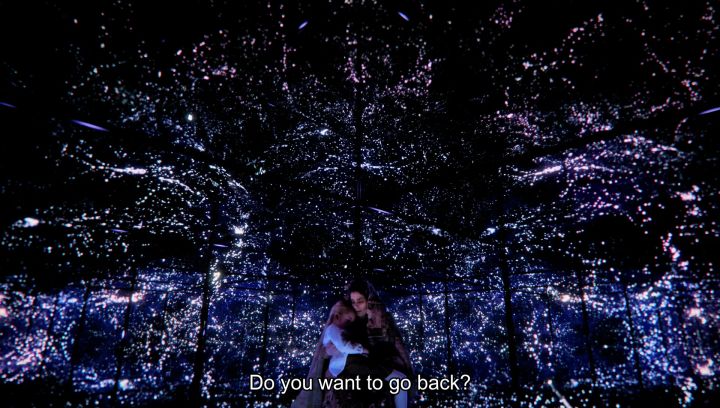

“I couldn’t tell if I was inside the earth or above it,” the OA says. “Why was the dark so dazzling?” These two lines suggest a union of opposites. So the Big House reflects an alchemical principle – “As above, so below.” As such it represents an axis mundi, a place that connects the worlds Above and Below, Past and Future, to the Here and Now.

“I couldn’t tell if I was inside the earth or above it,” the OA says. “Why was the dark so dazzling?” These two lines suggest a union of opposites. So the Big House reflects an alchemical principle – “As above, so below.” As such it represents an axis mundi, a place that connects the worlds Above and Below, Past and Future, to the Here and Now.

Within the Big House, Nina is given a vision of the future, and she’s given a choice. Khatun asks her point blank, “Do you want to go back?” And again, the hairs on my neck stand up – for as a devotee of LOST, the phase “go back” is poignant and resonant with meaning, for in my interpretation it very much suggests death and rebirth – in LOST, to “go back” is to die and have one’s consciousness travel back in time, creating a loop of eternal return. Remember this when we get to Homer.

Khatun then says that Nina will know great love, but also great suffering; when Nina says “back,” Khatun takes her sight from her, rendering the child blind.

There is always a price to pay for future knowledge.

I Was Blind, but Now I See

Another strong metaphor in The_OA, and in many spiritual traditions, is the use of “sight” and “blindness” to refer not to the physicality of eyesight, but to the ability to see the invisible self, one’s spiritual condition, and the divine nature of the Universe. In John 9, for example, Jesus heals a blind beggar, one with a reputation for living in sin. “I was blind, but now I see,” the beggar testifies. To take it literally is an impossible miracle, of course, but to take the story metaphorically, on the other hand, is entirely within the realm of possibility – the man previously did not see his own invisible self, and as such lived in the “sin” of not recognizing his divine nature, but now he’s been enlightened and can live a better life. By the same metaphor do we get idioms like “having the sight” in reference to having the ability to see the future; “clairvoyant” literally means “clear sighted.”

In this light, OA’s reactions of faint disgust at all the questions of “How did you get your sight?” make a lot of sense – it betrays those people as being more blind than she ever was. The “sight” she has isn’t just her physical eyes working – no, she can see into people’s souls, be it the teacher who’s lost her way to the wayward boy whom everyone thinks is a violent empty hooligan but who she recognizes as being too sensitive to the travesties of the world around him. It’s this same kind of sensitivity to the suffering of the world that Khatun refers to just before she takes Nina’s eyes, ostensibly to protect her – and yet, ironically, it is her blindness that actually helps her to see, for it forces her to listen, to pay more attention, and to understand that her internal resources were far greater than anyone else could see in her – what leads people to “underestimate” her as she puts it.

There’s a great scene in the clothing store where she talks about this with Steve while she’s trying on clothes (for OA, the outer self is simply like a set of clothes). “Maybe try closing your eyes,” she says, and so he tries it—but he lacks much in the way of concentration, and it’s barely a second later that he mouths the word “Boring,” which OA picks up on immediately, though he’s got his back turned to her while she’s in her dressing room. “Yeah, it’s boring at first,” she says, and this shocks him. He looks at her through a crack between the dressing room doors, and only his eye is visible through the seam; he is now looking at her with a different understanding than he had before, he’s starting to see her invisible self. (Now, how did she know he said “boring” at that moment? Maybe she’s psychic, but we don’t have to go there; maybe she’s got very acute hearing, and could pick up on Steve’s mouthed word… or maybe she’s just so in tune with the experience and has read Steve so well she could accurately predict his reaction. We don’t have to resort to the supernatural to explain this, but even within the realm of the realistically possible it’s still pretty amazing how perceptive she can be.)

There’s a great scene in the clothing store where she talks about this with Steve while she’s trying on clothes (for OA, the outer self is simply like a set of clothes). “Maybe try closing your eyes,” she says, and so he tries it—but he lacks much in the way of concentration, and it’s barely a second later that he mouths the word “Boring,” which OA picks up on immediately, though he’s got his back turned to her while she’s in her dressing room. “Yeah, it’s boring at first,” she says, and this shocks him. He looks at her through a crack between the dressing room doors, and only his eye is visible through the seam; he is now looking at her with a different understanding than he had before, he’s starting to see her invisible self. (Now, how did she know he said “boring” at that moment? Maybe she’s psychic, but we don’t have to go there; maybe she’s got very acute hearing, and could pick up on Steve’s mouthed word… or maybe she’s just so in tune with the experience and has read Steve so well she could accurately predict his reaction. We don’t have to resort to the supernatural to explain this, but even within the realm of the realistically possible it’s still pretty amazing how perceptive she can be.)

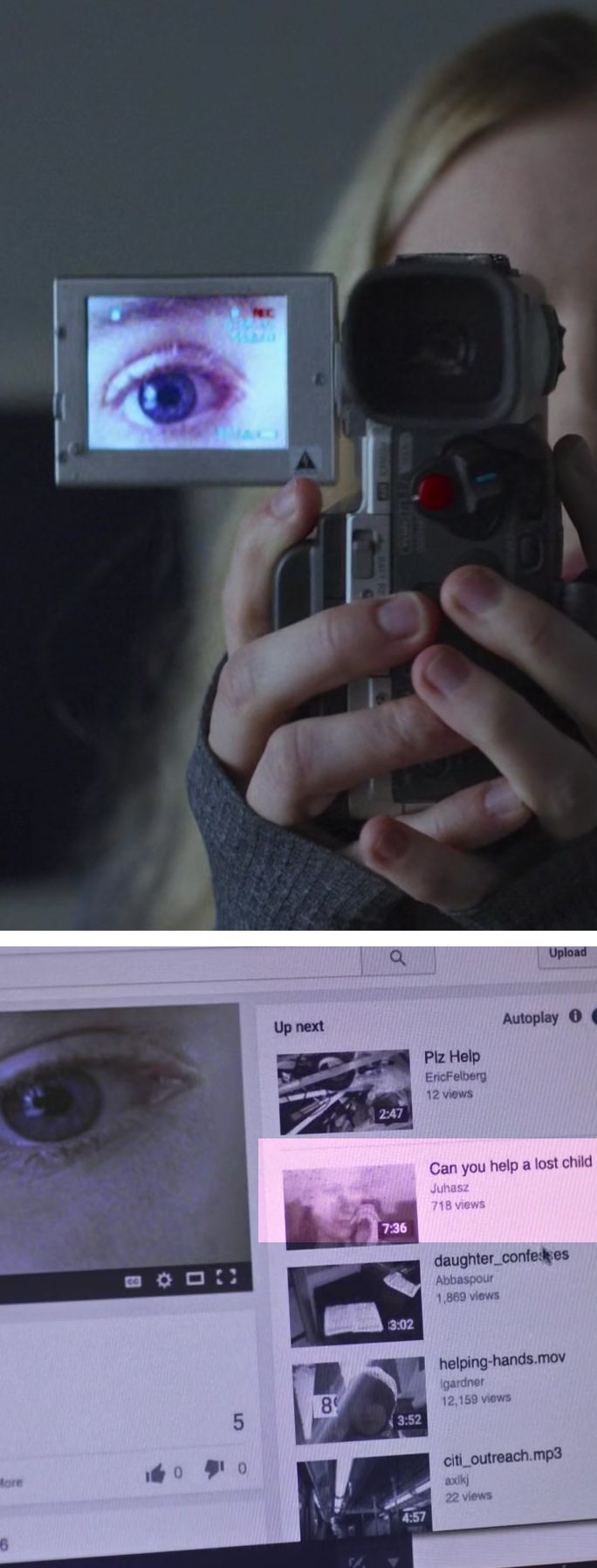

The other important “eye shot” of this chapter is the close-up of OA’s eye in the video she makes asking for help. Which, as it turns out, is the first thing Betty Broderick-Allen, the schoolteacher, sees when her curiosity gets the better of her and she starts googling “the oa” – and this is what she finds after telling the principal on the phone that OA was obviously “disturbed” because of “those eyes.”

By the way, when OA told the Five to close their eyes at the beginning of her tale, did any of you listen and do what she asked? I did… and it actually provided a somewhat different experience, because of something I didn’t see the first time around.

Anyways, it’s amidst the clamoring to “see Prairie’s eyes” when Nancy and Abel bring her back from Saint Louis to Michigan–

(Interesting choices for locations, by the way. Saint Louis, where I lived for over ten years, is called the “Gateway to the West” by the locals, sitting on the west bank of the Mississippi River, a river that’s incredibly huge and dangerous even in this day and age. Between the Poplar Street Bridge and the Eads Bridge stands The Arch, which is kind of like a Silver Rainbow in effect, gleaming metal that reflects all kinds of light. So OA basically passes through a gateway to return to mundane reality.

And Michigan is that reality – my home state, and where I recently discovered some new aspects to myself, or rather uncovered some things that were long dormant, but that’s another story entirely.

Michigan is comprised of two peninsulas, the Upper and the Lower, which Michiganders usually depict using their hands, as the Lower Peninsula in particular is shaped like a mitten. It’s called The Great Lakes State, because this shape is created by how it sits between four of the five Great Lakes of North America. The largest football stadium in the country belongs to the state’s titular university — and LOST fans should look up the stadium’s nickname to gain an understanding of why Karen and Gerald DeGroot were based in Ann Arbor, at least according to my personal mythology. Most recently, Michigan was a tipping point state for the recent US elections, as it has been ravaged by job losses… and then there’s Flint, where thousands of people have been poisoned by lead-contaminated water. Michigan has a kind of “backwoods” character to it, despite the presence of the somewhat cosmopolitan Detroit and its surrounding suburbs.)

–that another interesting shot occurs, when Abel shuffles his daughter through the gathered crowd to their relatively modest house. OA pulls a blanket over her head, and this has several implications (besides somewhat resembling a similar image in Doctor Who’s Listen) – first, it demonstrates that OA isn’t ready to be “seen” yet, which is congruent with her general unwillingness to share her story to the world. Second, though, we get a view of the world around her as seen through a “veil,” which makes everything seem hazy and gauzy and a bit unreal, and which highly suggests that this is how the mundane world “looks” at itself; there’s an element of blindness here. Even the flowers that have been sent to the Johnsons’ are all covered in plastic, veiled from actual life.

Likewise, the world may not be ready to really see OA, either. The nurse at Saint Louis Hospital says that the scars on her back are “really difficult to look at.” As we mentioned earlier, the woman in the car on the bridge who saw OA let go didn’t really want to look. And those who do want to see OA aren’t really looking at the invisible self, they’re too preoccupied with her eyes, or her scars, or her whereabouts… or their memories of the young woman who disappeared 7 years ago.

The Johnsons

Nancy and Abel certainly aren’t ready to see, despite being so liberal in their outlook. How can you see someone if you don’t fully trust her?

We don’t get much from Abel in this chapter, other than being reminded that he’s betrayed Nancy’s sense of privacy and decorum by sharing sensitive information with the insensitive Winchells – namely that “the doctors” wanted OA committed. Interesting name, Abel, very biblical. Despite being the second son born to Eve, he’s taken as an allegory to “hunter gatherers” seeing that he’s a herdsman, with the old shepherds being supplanted by the new agriculturalists (represented by Cain).

Nancy is given rather more depth. We really get a sense of her ambivalence regarding her daughter. On the one hand, she’s willing to eschew “hospital guidelines” and keep the doors unlocked. On the other hand, she’s collected up all the knives in the house and tucked them away in her desk drawer. Interestingly, she refuses to give up the password for the household’s internet. (When the computer says “Prairie, failure to authenticate,” in response to OA’s feeble hacking attempt, it’s like it’s saying OA herself has failed to “authenticate” as “Prairie” in the eyes of her adoptive parents.)

But it’s not that Nancy doesn’t want to know, doesn’t want to see. She very much wants to know her daughter’s secrets. But it’s the nature of the secrets that she wants to know that ultimately creates distance between her and OA. She wants to know how OA can see. She wants to know about the scars. She wants to touch her body. She isn’t looking for the invisible self, she’s still focused on the surface. So she is shut off from her daughter’s spirit like pretty much everyone else.

There’s an interesting resonance in the Johnson house, by the way – they take the doors off of OA’s room, a mirror to OA’s request that the Five leave their doors open as a gesture of faith to “invite” OA into their lives. But as is the case with many reversals, in this instance the Johnsons don’t give OA a choice; they exercise power over her, removing the door by force.

In this respect they’re not much better than the Winchells, who practically force their way into the Johnsons’ home, though at least they have the courtesy to take off their shoes; unlike OA, whose feet are bare (and terribly bruised, another sort of religious reference), they keep their socks on, still maintaining a metaphorical barrier to the touch of the “sole.” Instead of trying to connect to the Johnsons, Mrs Winchell accuses OA of “identity theft,” and implies sexual impropriety; on one count, though, she’s inadvertently right – OA has pretty much stolen away the identity of “Prairie Johnson,” or at least the Prairie that the Johnsons thought they knew.

Steve

Steve

Another synchronicity – their Winchell’s son, Steve, with whom OA develops the beginning of a friendship, says that the change in his teacher, Mrs Broderick-Allen, is like “Invasion of the Body Snatchers.” Steve is actually a source of all kinds of intertextual references in this chapter, so maybe we’ll take something of an Exegesis-style intermission at this point. Informally, of course.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers was a 1956 film ostensibly about alien “pod people” who, like doppelgangers, take over other people’s live, with all the physical features and memories of their hosts, but without any emotion. Dr Miles Bennell, a psychologist, starts getting clients who complain that their loved ones have been swapped by identical imposters. This is actually a medical condition, but here it becomes literalized – the alienation and dissociation of people becomes buried as metaphor within an extraterrestrial alien invasion.

MILES: In my practice, I’ve seen how people have allowed their humanity to drain away. Only it happened slowly instead of all at once. They didn’t seem to mind.

BECKY: Just some people, Miles.

MILES: All of us — a little bit — we harden our hearts, grow callous.

The people who’ve been lost, it’s like they’ve been brainwashed by a cult, or at least the post-war fevered imaginings of a cult. But this is exactly how the Johnsons have to feel about their daughter, just as Steve recognizes that Betty Broderick-Allen is not the same person he knew the day before. Her consciousness has shifted, and that’s very disorienting to other people who assume a continuity of self. (There’s also a character named Miles in this chapter of The_OA: he’s the boy who “sings like an angel.”)

So here we have a movie that stands as a metaphor, not so much for the era of McCarthyism as some critics have posited, but for some profound changes in human society, and especially the loss of connection or “communitas”.

We might call the Body Snatchers “qlippothic” in their lack of emotion, their motivation so rooted entirely in survival that they have become mere shells (of course they emerge from pods). But then we’d have to call humanity somewhat qlippothic, too, or at least Western culture and its dire aversion and lack of acceptance of death itself. Finally, I just have to point out the eventual conversion of Becky in a mine – OA’s father was in the mine business. This has some interesting symbolic implications, which we will certainly return to at a later date. For now, let’s just reflect on the proper ending of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, where Miles runs from car to car, knowing the truth yet being seen as a crazy person, as a mirror to the beginning The_OA.

Next we have Strangers on a Train, a Hitchcock movie that Steve invokes as a way of “trading crimes” with OA, which no one would figure out because “strangers on a train” don’t have a discernible connection at all. This suggests that he doesn’t think he has a connection with OA, but he’d be mistaken, because he doesn’t understand the point of the movie, let alone his relationship with OA. In Strangers, playboy Bruno Anthony befriends tennis pro Guy Haines, and proposes a “perfect” set of murders – two people could murder for each other, thereby saving each other from their own motives, as well as providing each other opportunities for ironclad alibis. “I’ve got a theory you should do everything before you die,” Bruno says, proposing the murder swap.

Next we have Strangers on a Train, a Hitchcock movie that Steve invokes as a way of “trading crimes” with OA, which no one would figure out because “strangers on a train” don’t have a discernible connection at all. This suggests that he doesn’t think he has a connection with OA, but he’d be mistaken, because he doesn’t understand the point of the movie, let alone his relationship with OA. In Strangers, playboy Bruno Anthony befriends tennis pro Guy Haines, and proposes a “perfect” set of murders – two people could murder for each other, thereby saving each other from their own motives, as well as providing each other opportunities for ironclad alibis. “I’ve got a theory you should do everything before you die,” Bruno says, proposing the murder swap.

But in truth, he doesn’t run into Guy by accident – he knows so much about Guy and Guy’s relationships that it’s implicitly clear that Bruno ran into Guy on purpose. There’s a connection here already, and Bruno’s the one who made it. This fits neatly with OA’s suggestion that she “picked” Steve and that her run in with him at the abandoned house, asking for internet and passwords and stirring up their interest was part of her plan all along (even if she hadn’t known going into the big house that she’d need to convert a dog to do it). A plan made up on the fly, in all likelihood, but she first saw Steve doing back flips on the roof of the house, at night, while another boy, Jesse, filmed it on his phone. She says she needs “strong, brave, flexible” people, and that’s what she saw when she first saw Steve. She then made her own impression, and now Steve is doing what she’s asked for while thinking it’s his plan all along.

Another pop reference which not invoked by Steve, but rather witnessed by him, is the choir singing Pearl Jam’s “Better Man.” The song is about a woman who’s in an abusive relationship, but doesn’t get out because she doesn’t believe she can find a “better man” than the one she has. “Better Man” was originally an angry song, but in the past decade or so it’s been treated as a sad song – and here, I don’t think it actually refers to Steve’s girlfriend Jaye. For while Steve is admittedly an asshole, he actually wants to have a relationship with Jaye, but she’s just using him to get better at sex. Steve reacts with anger in the face of this failure to connect and the abandonment it applies, but this is ultimately rooted in sadness.

Finally, there’s a reference to Starbuck’s, and I couldn’t help but think of the rebooted Battlestar Galactica, and Starbuck’s actual fate at the end. “All of this has happened before and will happen again.” Eternal return. Don’t forget…

Finally, there’s a reference to Starbuck’s, and I couldn’t help but think of the rebooted Battlestar Galactica, and Starbuck’s actual fate at the end. “All of this has happened before and will happen again.” Eternal return. Don’t forget…

Anyways, the thing about Steve and media references is that he has a thing about mediating his own image. This is all “outer self” stuff – like how he sculpts his body. How he likes having his “skills” on camera, but doesn’t want his other side to be seen by anyone (hence the fight at the Abandoned House over OA’s camera). He has a YouTube channel, and imagines being a personal trainer to celebrities – to media stars. Steve is “mediated” in a sense. But what actually starts to bring him out of his shell is OA’s faith in him, that she’s actually interested in his interiority rather than his exteriority.

Funny, but this is actually quite intimate. Not sexual, but intimate nonetheless. OA doesn’t extend this intimacy to Nancy, for example. But, as she pointed out to Betty Broderick-Allen, you’re not really teaching if you’re not reaching out to those who are most in need, as opposed to those who’ll be okay whether you’re there or not. And Nancy, despite her shortcomings, is still seems very much a woman in need. However, Nancy won’t extend the same trust to OA that she’s wanting from her daughter. The street goes both ways. I’m tempted to call this a “mirroring.”

Homer Roberts

If there’s anyone OA is intimate with, though, it’s Homer Roberts. And he’s not even in the story yet! OA speaks to him via her camera. As if by recording herself, she can communicate with him. It’s somewhat inscrutable, and yet this is the moment when she’s the most open, and the least calculating:

“OA: Do you remember the night we pretended we were in real beds and we described them to each other? I’m in a real bed but I haven’t slept a single night apart from you. I’m scared, Homer. There are moments when I think I made you up. That’s why I need to see you. To be sure you’re real. I didn’t leave you behind. I would never. I am coming for you.”

There’s a lot of compelling stuff in this passage. Something about “remembering,” which we’ll get to shortly—but also a lovely union of opposites about “pretending” they were in “real” beds, which implies they were “really” in “fake” beds. We also get an actual expressed fear—specifically, a fear that she’s “made him up,” another play on what is fictional and what is real; she needs to see in order to be sure.

And then there’s the kicker—“I didn’t leave you behind.” Suggesting that what he might have imagined isn’t real. But that phrase “leave you behind,” ouch, reminds me of the religious concept of being “left behind” in terms of The Rapture. What must it be like  to be left behind? Abandoned in such divine fashion? Or to the be the one who can’t take others with you? This is coupled, then, with the motivation that will eventually make sense of all of OA’s choices in this episode—she’s coming for Homer.

to be left behind? Abandoned in such divine fashion? Or to the be the one who can’t take others with you? This is coupled, then, with the motivation that will eventually make sense of all of OA’s choices in this episode—she’s coming for Homer.

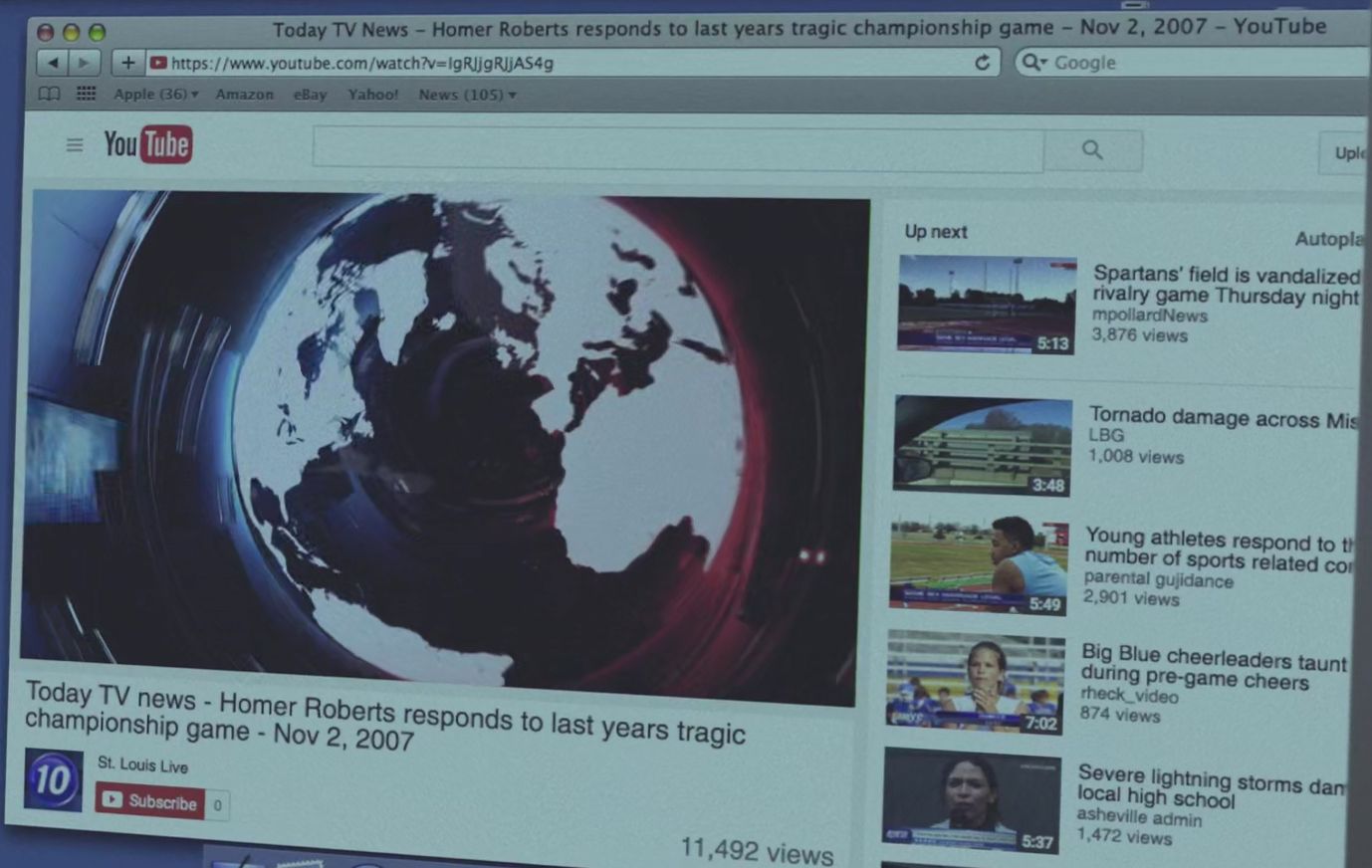

As it turns out, she’s not imagining him. OA eventually finds a YouTube clip of Homer Roberts shortly after his own near-death experience on a football field (and playing for a national championship, at that.) So many of the YouTube clips in the sidebar next to this have interesting little details surrounding them, lots of references to school violence:

— Spartans’ field is vandalized [before] rivalry game

— Young athletes respond to the number of sports related con[cussions]

— Big Blue cheerleaders taunt during pre-game cheers

— Severe lightning storm damages local school

In this context, one could paint Homer’s death as a result of school violence too, albeit the sanctioned school violence of college sports. And this is eventually mirrored by the attack on the school bus in OA’s early recounting of her tale.

Finally, though, in this video Homer does something very interesting. He’s being questioned about his near-death experience, about whether her knows what it’s like to die, but he deflects:

HOMER: Yes, I guess I do. But I’m back now. And I’m not I’m not leaving the championship game on a stretcher this year. I’m leaving with that ring.

Remember when I told you to remember about how the phrase “go back” in LOST refers to a kind of death and rebirth, wrapped up in a conceit of Eternal Return? Which is kind of a similar theme to Battlestar Galactica and Starbuck? Well, here it is again, Homer saying that he is “back” and he’s only leaving the “championship” with a “ring,” another symbol for eternity.

As he does this, he breaks the fourth wall and looks directly into the camera. Which is exactly how OA has tried to communicate with him.

Home

All this talk of Homer brings us to the title of this episode, “Homecoming.” Within the Near Death Experience community, a fairly commonly reported experience about the Other Side is that of a reunion with people who have gone before. Friends, family members, loved ones. This reunion is called a Homecoming.

The opening chapter of The_OA makes a rather big deal about coming home – and, of course, near death experiences. Let’s focus on the “home” bit. It’s a word invoked 11 times throughout the episode. A lot of it is when Nancy and Abel bring OA back to Crestwood (huh, my parents now live on Crestwood…) and everyone’s clamoring things like, “Welcome home, Prairie!” and proclaiming that she’s “home safe.” (Funny, Abel says, as they’re driving down the street towards the rush, that they “can’t reverse” at that point – they can’t go back.) Or when Nancy tells the Winchells that their daughter “needs to be home with us” and not committed. There’s even a blurb on the loudspeaker at the clothing store imploring shoppers to “take advantage of our home sale” – and all of these instances don’t even include OA’s search for a young man named Homer.

But Nancy is wrong (as she is about a lot of things) when she tells the neighbors that they “were here for Prairie’s homecoming.” Because in truth, OA isn’t Prairie anymore. Maybe she really wasn’t in the first place? Anyways, this house isn’t her home, not anymore at least. Most of all, though, OA didn’t have a homecoming because in her Near Death Experience she did not have reunion with loved ones who’d gone before.

And I could relate to that, because I didn’t have a homecoming either.

So there’s a profound irony to this episode, that it’s just as much about what OA didn’t have. What she lost out on. Not only did she not have a homecoming, everyone around her misunderstands what a homecoming can be in that deeply poignant sense, and they continually fail to realize that even in the conventional sense this really isn’t a homecoming for her. She’s still a stranger in a strange land. “Homeless Woman Jumps Off Bridge.”

Homecoming. It’s a word and a concept I actually started exploring thanks to LOST. (The word “lost” is spoken 8 times in this episode.) The 15th episode of Lost’s first season is called “Homecoming” and features Claire’s return to the people from the plane crash after being kidnapped and held captive by The Others who live on the Island. But Claire is suffering from amnesia… she doesn’t remember. When Claire opens her eyes, she screams and distances herself from the group at the Caves:

JACK: Claire? It’s okay. It’s okay.

CHARLIE: Claire. You’re safe.

CLAIRE: Who are you? Who are you?! Who are you people?!

Claire didn’t really have a homecoming, then, come to think of it. She ended up deposited among a bunch of strangers.

Remember

And then that episode of LOST gets into another theme (besides Charlie’s ostensible need to take care of people), that of memory and forgetting and remembering. And this, believe it or not, goes back to NDE experiences as well. “We have all forgotten that we were the one original being. So we live out our lives in the illusion of separateness,” says one Near-Death Experiencer. It’s not uncommon to have the feeling that “I remember everything” when dying, be that the knowledge of one’s life, now flashing before your eyes, or of a deeper understanding of the Universe. Even in traditional esoteric circles, there’s the idea of “anamnesis”—the idea that what knowing really is isn’t accruing new facts and figures, but more like remembering what we have previously forgotten. But we can’t remember everything, because that would be, well, like an experience of obliteration.

HAYTER: I’m a scientist, Doctor. The chance of inheriting the wisdom of all the Universe is an opportunity I cannot ignore.

DOCTOR: It will destroy you. You don’t understand what you’re doing.

HAYTER: Precisely, Doctor. But soon I shall know everything.(Doctor Who, Time Flight, Episode Three)

So remembering has to be gentle, easy, slow. Take it easy.

In this opening chapter of The_OA, the word “remember” appears 11 times, most frequently in the scene where the FBI first interrogates OA about her experience and whether she can remember any of it, to which she says, “I remember everything.” Mmmm. And, likewise, there’s a scene at the very beginning that suggests the same kind of amnesia that Claire demonstrates at the beginning of LOST’s “Homecoming.” Nancy and Abel enter OA’s room at St Louis Hospital wanting to see their daughter, but OA’s response is flabbergasting:

OA: Who are these people?

Only by touching Nancy’s face does OA remember who Nancy is.

But the most poignant scene about remembering is when OA visits Betty Broderick-Allen, while pretending to be the Outer Self of Steve’s step-mother. She can’t help but see Betty’s invisible self, shut off from the world around her. It’s in this conversation that “lost” gets constantly invoked – first, it’s in regard to someone that Betty lost, a sibling, followed quickly by reference to OA’s  friend Homer as well, presumably. Then it becomes a descriptor of Steve, who is both spiritually lost as well as the boy that Betty has lost as a teacher.

friend Homer as well, presumably. Then it becomes a descriptor of Steve, who is both spiritually lost as well as the boy that Betty has lost as a teacher.

When OA entered the room, she was positioned under an Emergency sign. So this scene is basically an emergency for her. She has to respond. But for her to respond authentically, from her interior or spiritual self, which is what’s ultimately motivating her all along, her outer self literally starts to crumble, as one of her fake nails falls off.

But this is what precedes OA actually starting to shine. We see her general philosophy emerge—she describes the interaction between teacher and student as, “It’s about you and Steve and the play, cast of two; setting, classroom; over many dimensions through time.” The world is a stage, life is an act (or perhaps a ritual), but it resonates in many places. This may sound dissociative, though as she points out, “It’s not really a measure of mental health to be well-adjusted in a society that’s very sick,” which is not actually an original sentiment.

She then says that she can help Betty “remember.” Betty has lost her way, has forgotten her first principles, and sure enough, simply through sharp empathy and a good cold reading of Betty (OA doesn’t pick up immediately that Betty lost a sibling, she just keeps prompting important relationships until she nails one) she helps Betty to remember. And Betty changes.

“Lost” is also the word used to describe to the FBI all the people OA saw at a “place” after a woman in a dusty car picked her up after she walked for days from a place she calls “nowhere,” and “nowhere” is also a description of The Island in LOST. “And the snow was seven feet high, but you could still make out many big houses behind big gates lost in the white. You asked me how I got my sight. The better story is how I lost it in the first place.” This, right after the show makes the striking decision to wait 57 minutes before starting the opening credits, where frozen water falls as snow upon the Moskva River winding its way through Moscow like a giant snake.

THE_OA Exegesis: Chapter 1

THE_OA Exegesis: Chapter 1

The_OA was released on Netflix in mid-December last year, and it was quite a hullabaloo – it dropped with very little advance notice, let alone much description of what it was about, and it quickly became a bit of a cult hit. More like something that a lot of people found intriguing, or infuriating; moving, or hokey; brilliant, or an abject failure. Mostly on the basis of its plot and especially its ending, combined with the ambiguity of the final shot and of course the question of whether OA’s narration is unreliable or not.

I get that. But all the criticism I’ve seen so far has been… so… literal in its take on this show.

Everyone’s more concerned with what “really happened” as if this were gossip or something. It makes sense, though, in a culture like ours, that something that’s so blatantly metaphorical would elicit such a reaction. For to be sure, The_OA is blatantly symbolic and metaphorical, and yet there’s almost no discussion I can find about this aspect of the work.

So that’s what I aim to do – to look at the underbelly of this show. Not only will seeing it in this light bring forth some other dimensions to the work, it will actually help clarify what (I think) is actually going on, or at least on what side of the great divide the show stands given its apparent ambiguity.

One place where it definitely stands, all mysticism aside, is as a critique of society. Consider the reactions of so many people – the woman in the car on the bridge, who doesn’t want to look at OA. The Winchells, who want to castigate OA for daring to challenge their narrative of their noncompliant son. The gawking curiosity of not just neighbors, but medics and media and even family – how did you get those scars, how did you get your sight, can we look at your eyes? The society of spectacle.

And then there’s the reactions of institutional power – the doctors wants OA committed because she doesn’t comply with their requests for information. The school wanting to expel Steve, who rebels against their authority; his parents threaten to send him to military school. OA’s parents try to box her up by forcing open her doors; they seek to limit her freedom. Even Steve himself doesn’t know how to respond to OA when she first confronts him at the Abandoned House asking for internet; only when she subdues his attack dog does he realize that the tactics of “power over” that have been used to manipulate him won’t work on her.

This is how power deals with non-compliance: with threats of imprisonment, violence, or abandonment. So how do we deal with power? And just as importantly, how do we not?

Maybe Pearl Jam has something to say about this.

Over Troubled Water

Over Troubled Water

In The Time Traveler’s Wife there’s quite a lot of symbolism involving fish and birds. Fish imagery, or anything that lives in the water, is invoked over and over again in reference to Clare’s parts, the wife who, weary traveler, must always take the slower path of ordinary linear time. Henry’s parts as the time-traveler, on the other hand, are typically decorated with bird imagery. They’re very different experiences, swimming and flying.

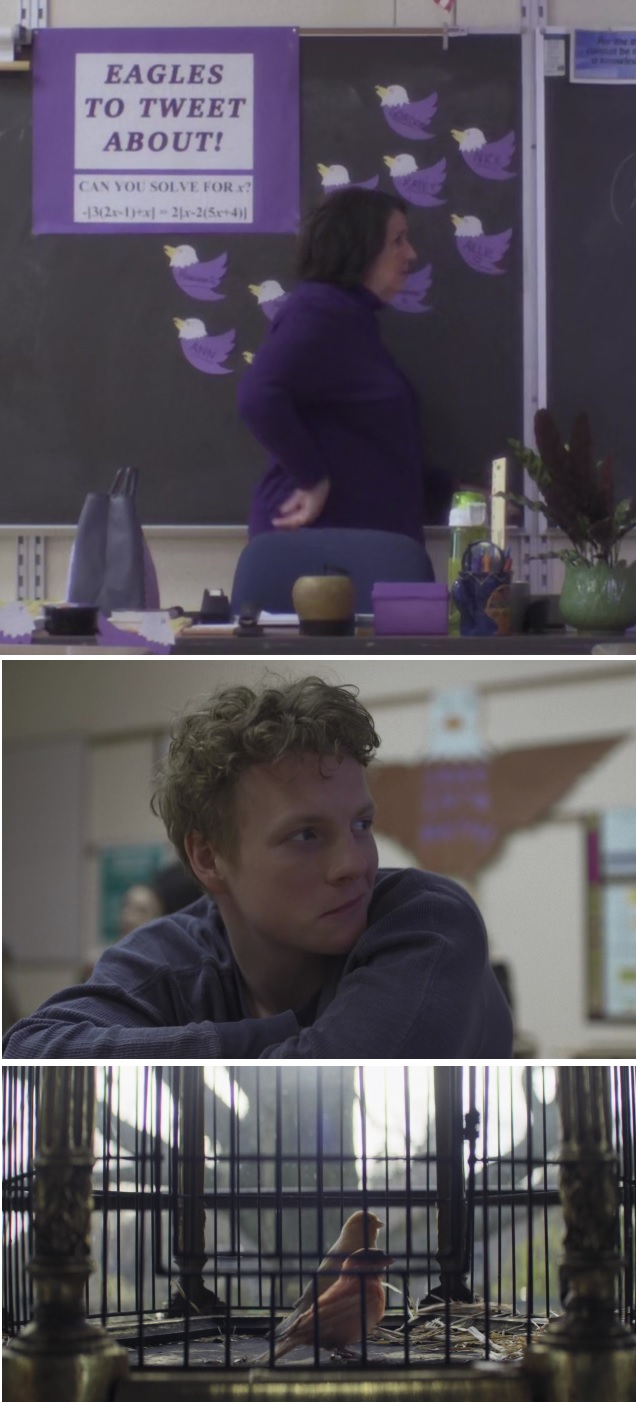

I kind of get a similar vibe with The_OA, not so much with the time-traveler angle, but just with all the bird imagery and water imagery that’s presented here. I mean, there’s just so much of it! Let’s start with the birds. When we first meet Betty, Steve’s math teacher, she’s putting “Eagles to Tweet” on the blackboard, and they linger over her shoulder during the conversation with OA; at one point Betty challenged OA to “talk turkey.” Betty is quick to change. (Buck’s father, on the other hand, has pictures of fish above his bed, and he misgenders his son by calling him Michelle; this father is definitely not flying.)

In the very next scene, when Steve has discovered that Betty’s attitude has flipped, we see him in a shot with a giant eagle on the wall behind him, wings outstretched. Steve is also someone who does backflips on the roof of the Abandoned House, and it’s standing on the back of his bicycle that OA smiles and closes her eyes; it’s as if she were flying. No wonder the scars on her back remind me of the leftovers of clipped wings.

When OA’s video posts on YouTube, Buck messages Alphonso. The messages chime with “chirp” sounds on his laptop.

And then there’s the scene with Nina as a child eating breakfast with her father. She eats birds eggs – not ordinary hens’ eggs, but small light blue eggs the same shade as her blouse. There’s a birdcage behind them with delicate edible birds inside. When she’s on the schoolbus later that morning, she complains about a feeling in the pit of her stomach, “like the eggs were sitting there stuck, unbroken.” This immediately precedes her childhood near-death experience.

The name “Nina” is suggestive, by the way. Well, in some ways, and not in bird ways – here’s where we transition to fish. There’s much to the etymology of “Nina.” It’s a feminine diminutive suffix to other names, especially in Russian; even on its own it can mean “little girl.” But consider that her near-death experience is with a woman who speaks Arabic – so perhaps another etymology is called for: Nina is also the name of a Babylonian/Assyrian fertility goddess on par with Ishtar and Inanna, the patron goddess of the city of Ninevah, and her name was written using glyphs representing a fish surrounded by a house. And there was a Saint Nina who introduced Christianity to Georgia in the 4th Century; Christians often identify themselves with the ichthys, a fish symbol.

The name “Nina” is suggestive, by the way. Well, in some ways, and not in bird ways – here’s where we transition to fish. There’s much to the etymology of “Nina.” It’s a feminine diminutive suffix to other names, especially in Russian; even on its own it can mean “little girl.” But consider that her near-death experience is with a woman who speaks Arabic – so perhaps another etymology is called for: Nina is also the name of a Babylonian/Assyrian fertility goddess on par with Ishtar and Inanna, the patron goddess of the city of Ninevah, and her name was written using glyphs representing a fish surrounded by a house. And there was a Saint Nina who introduced Christianity to Georgia in the 4th Century; Christians often identify themselves with the ichthys, a fish symbol.

I like the goddess reading the best.

Anyways, as a little girl, Nina is also marked by an awful lot of water symbolism. She calls her premonitions a recurring dream of being “trapped in an aquarium,” as if she were a fish, in other words. Her father’s response to that dream is submersion in a pool of ice water, to be colder than the cold. (Nancy is told by Abel not to let her food get cold; when OA recovers from her jump into the Mississippi, she’s told she had hypothermia. Yeah, we’ll be covering the “cold” in future entries.)

The one time that OA even approaches intimacy with Nancy, it’s when she’s sitting in a bathtub. This scene is marked by the question of whether OA is “still hearing voices” to which she says, “I’m not hearing anything.” (Neither am I.) But it’s here that Nancy tell a tale of empathy of when OA was young and just learning to cane, and when she smacked into a wall and split her forehead opening (suggestive of opening the Third Eye), Nancy felt it, and knew OA was her daughter. OA then confesses to Nancy that she can’t bear to tell her story to her yet, not because she doesn’t want to, but because it would hurt Nancy, and she can’t bear the thought of hurting her. (To be fair, though, her eyes dart at the end of this confession, so she might be lying.)

It’s the actual drowning, though, that’s just laden with symbolism. Because she’s had dreams of this, Nina can actually respond to the situation – she dives under the water and examines her surroundings. “There’s a light beneath us. Maybe one of the windows is broken. If we swim deep, maybe we could make it out.” Which is very much a metaphor in tune with the oft-reported “tunnel of light” of so many near-death experiences. When Nina finally gets out, but fails to reach the surface, we see her in a shaft of light, suspended practically in the middle of the water as if she were suspended in mid-air, as if she were both a fish and a bird.

“We were a message, see?” Yeah, and more than one kind of message at that. I love dialogue that can accrue extra meanings.

She dies, and then we see her curled up in the fetal position in a pool of water, ready for rebirth in the Big House. This water is what connects her between the Ordinary World and the Other Side. The water, which is a place of death, is actually revealed to be a bridge.

You know who you are. Drink up.

February 14, 2017 @ 1:53 pm

Welcome Back Jane! And what a way to come back with (though, I suppose in hindsight there was really only one way (well, not really, but still, of course you were going to talk about this show)). I look forward to seeing what comes next.

February 15, 2017 @ 3:21 pm

Thank you, Sean, it’s good to be back. 🙂

October 23, 2019 @ 11:30 pm

You did not try to look in google.com?

Rather amusing phrase russian nude women, russian women singer, [url=http://alovingwife.com]Home Page[/url] hot women russian

November 8, 2019 @ 10:00 am

This message, is matchless))), it is interesting to me 🙂

In my opinion you are not right. Let’s discuss it. Write to me in PM. валюта bitcoin, bitcoin создатель, [url=https://paynote.eu]valor actual del bitcoin[/url] bitcoin fund

December 20, 2019 @ 12:04 pm

Excuse, I have removed this message

I consider, that you are not right. Let’s discuss. Write to me in PM, we will communicate. you buy steroids in, to buy steroids on the, anabolic pills [url=https://anabolicos-naturales.info/oral-steroids.html]page[/url] buy steroids from a

February 15, 2017 @ 8:59 am

I’m very glad you’re writing about this, as it’s the most Eruditorum thing I’ve seen in a while. When the opening credits appeared, I couldn’t help but burst into awe-struck laughter. Whatever its flaws, I’ve been flawed by the audacity of this show. And I think it has definitely earned the kind of deep reading you’re giving it. I’d like, at some point, to address some of my reactions to your reading, and I’m sorry to be engaging with it indirectly in in this comment.

But I wanted to take an opportunity, since I don’t yet have a home, to talk about something very specific, an Earthly aspect of this show which has, to my mind, gone largely unexamined. As a blind person, I absolutely dreaded this, based on the blurb. I do not like the lost/restored sight trope, partly because it casts blindness as being an inferior state, which doesn’t fit with my worldview, but also because it associates sight with identity. If someone has lost their sight, its return completes/restores them.

I also have issues with mysticism around blindness, because that suggests it might be a superior state. It’s not part of my identity. Like birth, death and marriage, it’s something I’ve reacted to, and every blind person’s reaction to being blind is different.

So why did I not hate this show? I’ll talk only about the first episode for the moment. A few mundane things pleased me, e.g. She used a real screen reader, and I cheered. But what was more interesting was the fact that neither blindness nor sight were treated as superior states. It was clear that the OA was a person with superior insight, but it wasn’t implied that she gained this from either losing or regaining her sight. When she’s overwhelmed, she retreats into blindness, which in that moment feels like a place of safety. She also retains some of the habits of a blind person. But she also uses sight to her advantage throughout the episode, and also recognizes the advantages of her sight when she needs it. She’s always watching people carefully, and observing a lot about them very quickly. In this way, her temporary blindness, which could have been a terrible plot device, is treated as an experience, with some good and bad aspects, which she reacts to differently depending on how she feels. The restoration of her sight didn’t complete, or break her character. She didn’t go back.

When Nina loses her sight, it seems like the cruel and brutal act of a higher power. But it’s done out of a desire to protect her, and so despite its Old Testament vibe, it’s neither punishment nor reward, in a way which strongly speaks to my own personal experience. There’s a lot more to unpack about this which I didn’t anticipate when I started writing. The politics aren’t perfect, and there are many I’m sure who would disagree with me. But personally, I mostly respect the way blindness is treated here, and I honestly think it’s a uniquely nuanced engagement with an issue which is frequently treated very badly.

Thanks for reading, if anyone did. Look forward to the next entry.

February 15, 2017 @ 3:39 pm

Thank you for this insight, JDX. I’ve never been blind, though I’m definitely myopic and I have lost hearing in one ear. (Some point soon I really have to learn how to sign.)

I lived with a blind man for several years, though, and there were touches in this episode I really appreciated — like the same computer voice software, for example, that he used. The keyboard with braille on the keys.

But I really like your point about how there can be an Old Testament vibe to stories of blindness — it’s one thing to apply this experience as a metaphor, it’s quite another to literalize it as indication of divine favor or otherwise. And in this show, the people who take the restoration of sight as a “miracle” and who focus on that aspect of OA’s journey, rather than her interiority, are treated with disdain. The show is aware of this dynamic, and something to say about it.

Anyways, I’ll be looking forward to your future comments, and don’t feel like you have to hold back your reactions to my essays — you don’t have to wait until the end. I’m happy to incorporate other lines of thought into these pieces, but of course it’s your choice. Forking paths, and all that.

Yours,

Jane

February 15, 2017 @ 12:09 pm

Oh yes! Welcome back Jane. I’m so glad you’ve chosen to unpack (of course it’s what you do when you come home) the OA. I’ve yet to complete it. I put it on hiatus after the fourth episode. I’m not sure if I was enjoying it or even understanding it. Of course its metaphorical metatextual, unreIiable narration and open ended attitude to plot development immediately conjured LOST to me too, and the more interesting corners of Moffat’s writing it has to be said. I will return to it now guided through the murkiness by the light of your exegesis.

I was struck by your analysis of the open door thing. The opening of the front door by the ‘woman of the house’ during the meal is an important part of the Seder or Passover ritual in Jewish tradition. It symbolises the ‘openness’ of the house to strangers (anyone outside should be invited in to partake of the meal) and the fearlessness of the family in observing the ritual (there are many stories in my family and I’m sure others regarding the bravery of following this edict in Nazi Germany or Tzarist Russia for instance).

It is also a ‘just in case’ action, tradition has it that the angel Yeshua will appear at Passover to herald the coming of the Messiah or, in some versions, the Messianic age. So any mysterious stranger should be welcomed lest you miss out on ‘entertaining angels unawares’. This possibility used to fascinate me as a kid.

Thanks for the water.

February 15, 2017 @ 3:48 pm

Oooh, this gives me chills, Anton. Obviously I’m not Jewish, nor are the rituals of Judaism something I’ve studied, so thank you so much for your perspective on this, and please let us know when you realize any other similarities. 🙂

As to entertaining angels unawares, it’s a funny thing. I mean, if you treat every stranger as a potential angel, that really changes the kind of interactions you have with other people. When I studied LOST back when it was airing, I often had the feeling that some of the people I was talking to on the Internet were people who were actually behind the scenes in the production of the show, or friends thereof. There was a rumor that the writers, for example, had recruited their allies to play on various forums to encourage elaborate theory-building and delve into some of the more interesting… implications of the show.

Talking to someone with the idea that they know way more than me, which for me is contradictory to my natural arrogance, was a humbling experience; I think it made for better relationship-building as well as being more open minded and flexible to my own approach to the show.

Of course, there are other possibilities to be aware of when we think along these lines, as the next chapter of The_OA aptly demonstrates…

February 16, 2017 @ 10:26 am

The aspect of your writing that I most enjoy Jane is the connections you construct which I wouldn’t necessarily have seen and the paths they lead us down. So it’s cool that I was able to reciprocate with a path of my own.

Despite my ethnicity I’m no expert on Judaic lore. My knowledge comes mostly from childhood memories and subsequent dabbling in kabbalistic imagery, tarot, magick etc.

I talk a little about that on the podcast ‘But…That’s Impossible’ which my friend Amy and I host.

https://www.podbean.com/media/player/939cn-6754d7?from=yiiadmin&skin=2&share=1&fonts=Helvetica&auto=0&download=0

Please give it a listen if you have time and let us know what you think.

I’m certainly looking forward to seeing what paths your OA Exegesis takes us on.

February 15, 2017 @ 2:22 pm

You’re covering this! Yay!

I absolutely love this show, and have served as a vector to assist its spread as a sleeper hit (everyone I’ve talked to about it has loved it, and other viewers seem to be doing the same). Yes, you could call the thing self-consciously esoteric (like another flawed work I deeply love, Grant Morrison’s ‘The Invisibles’), but so what? The thematic and motif depth is real.

(My wife, who is an intelligent viewer but demands a clear narrative or character through-line, likes this even more than I do, and prompted us to watch it twice, which is nice and says something about why the show works.)

February 15, 2017 @ 3:58 pm

Patman, I’ve tried getting my Mom to watch this, but I haven’t had any luck. She’s someone who appreciates questions of narrative reliability, but she’s so damn skeptical and disdainful of anything that even remotely smacks of mythology… so I’ve had no luck. I’m glad, though, that you’ve had more success. 🙂

And sure, The_OA has its flaws, but isn’t this the way of the Universe? What with all the entropy and suffering, and how all the people of the world… we all have our failings. Or, maybe this idea of “flaws” is itself flawed, for things are what they are — “it is what it is” seems to be gaining cultural currency as a phrase the last few years — and maybe it’s only our own ideas of what “should be” that make other things and other people seem flawed. In other words, I can’t help but wonder if “flaws” actually exist only in our heads, a derivative of our “maps” not matching the “territory” (which is always going to be the case, necessarily, as no map can fully capture the territory without being a duplicate of the territory, and then we need another map to capture the existence of two territories, omg its turtles all the way down) and that as such “error” is itself a fiction.

Um, that last sentence, it got away from me, yeah.

February 15, 2017 @ 5:54 pm

re: Flaws = Good

Oh, absolutely. If I wanted mechanical precision and a lack of sharp edges, I’d watch, I don’t know, the latest Marvel movie again. Or something. Something with as much sheer ambition and bravado as The OA (as you point out, leaving the title credits for the last two thirds of the first episode, and not really laying down the premise of the work until…the third…one?) is bound to have all kinds of squiggly bits. It is, as you say, what it is.

February 16, 2017 @ 8:52 pm

Hurried over here as soon as I knew this was up, and you didn’t disappoint. I love how you’re integrating the themes and ideas with your LOST exegesis (a comparison which struck my to a certain degree but I hadn’t fully articulated in my own head). Looking forward to the rest!

February 18, 2017 @ 6:22 pm

So glad you’re here, Kat, and that you enjoyed the first entry!

November 26, 2019 @ 6:44 am

Very interesting, good job and thanks for sharing such a good blog. Your article is so convincing that I never stop myself to say something about it. You’re doing a great job. Keep it up and look at the link my bio to know How to Download & Save Facebook Videos on PC, Mac, iPhone & Android