I Never Liked This Planet (Invasion of the Dinosaurs)

It’s January 12th, 1974. Between now and February 16th, twelve people will die in an IRA bmombing of a coach bus on the M62, and a hundred and seventy three people will die in a fire in Sāo Paulo. The implementation of the three-day week will cause massive economic strain on the United Kingdom, which does not directly kill anybody, but is linked to large spikes in crime and mental illness. In addition, Batman creator Bill Finger will die of a heart attack and movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn will die of old age. Beyond that, the world moves ever closer to the eschaton and Invasion of the Dinosaurs airs on the BBC.

It’s January 12th, 1974. Between now and February 16th, twelve people will die in an IRA bmombing of a coach bus on the M62, and a hundred and seventy three people will die in a fire in Sāo Paulo. The implementation of the three-day week will cause massive economic strain on the United Kingdom, which does not directly kill anybody, but is linked to large spikes in crime and mental illness. In addition, Batman creator Bill Finger will die of a heart attack and movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn will die of old age. Beyond that, the world moves ever closer to the eschaton and Invasion of the Dinosaurs airs on the BBC.

There are two key strands of thought in Invasion of the Dinosaurs, both of which come filtered through the oddities of Malcolm Hulke’s politics. The first, as noted by Tat Wood in About Time, sees Hulke responding to The Green Death by offering his own take on the conspiracy-minded thriller within Doctor Who. Wood proceeds to suggest several antecedents for this, making a selective but nevertheless fairly broad accounting of the genre to show where Hulke might have been pulling in contrast to Sloman and Letts, whose work Wood frames primarily in terms of monster movies.

The real place to look for the change, however, is in the two stories’ treatment of the left. In The Green Death, Professor Jones and the nuthutch are presented as an idyllic alternative to Global Chemicals and indeed to modernity in general. They are without fail good people who do the right thing—people into whom our trust can and should be placed. In Invasion of the Dinosaurs, meanwhile, the left are the bad guys. Brilliant visionaries with noble and respectable priorities consistently turn out to be antagonists, whether they’re plotting the wholesale slaughter of most of the world or angrily crushing all dissent and rejecting any threats to their worldview. Lip service is constantly given to the importance of environmentalism, but actual environmentalists all turn out to be the villains.

It is difficult not to read an autobiographical bent in this. A former member of the Communist Party writing a story in which the leftists are all corrupt, megalomaniacal, and profoundly closed-minded is difficult not to read as a settling of accounts, with Hulke writing his own frustrations with leftist radicalism into the story. Certainly what he ends up with is a laundry list of standard leftist failure modes—indeed, not for the first time within Hulke’s Doctor Who career he’s ended up writing Doctor Who that serves comfortably as right-wing propaganda. The failures of Grover and Ruth are essentially the things that the Tories and Republicans accuse leftism of doing, whether silencing dissent or actually being mass murderers. Ruth, in particular, given that she’s played by Carmen Silvera, who would eventually become well known as a comedic accent from her appearances on ‘Allo ‘Allo, feels almost exactly like what Gareth Roberts would do with Doctor Who if he weren’t too much of an absolute asshole to actually get employment on it anymore.

In the face of this, the Doctor’s lip service about environmentalism feels intensely hollow. His final observation that greed is destroying the world is presented with agonizing pessimism, with the Brigadier shrugging it off and everybody going back to normal. The story believes in ecological catastrophe while adamantly rejecting the idea that there might be anything to do about it. It’s perspective is of an ex-leftist not in the sense of having abandoned the desires or ideals, but in the sense of having abandoned all actual hope or investment in progress. This is relatable in its bleakness, but still striking within the glam aesthetics of the Pertwee era.

Which bring us to the other major strand of this story. The Pertwee era, fueled by the fact that its production schedule was appreciably less likely to kill its lead actors, stretched on for five years where the Hartnell and Troughton eras stopped at three. And a practical result of this was that in its later years it discovered nostalgia for the first time in the series. This began, unsurprisingly, with the tenth season, which opened with The Three Doctors before coming around to a retro-fueled story that deliberately imitated the Hartnell-era The Daleks Masterplan. But with Pertwee’s final season, with everyone reflecting on the impending end of an era, the gaze turned inward, with the Pertwee era being largely nostalgic for itself. Across five stories we have another retro Dalek story, a remake of a Season Nine story, an era-capping grand statement, and, well, this.

On the surface, this is not an unduly nostalgic story. It’s a UNIT story, sure, but that’s only nostalgic inasmuch as the show is no longer earthbound and so doesn’t have this as a forced default anymore. And yet throughout the story there’s a recurring motif of UNIT being treated in a way rooted in its intense familiarity. From the wry humor of the Brigadier’s meeting with the Doctor to the overstated nobility of Benton’s invitation to the Doctor to knock him out, this is a story that leans on the length of time that UNIT has been around and the way in which the audience is assumed to have affection for them.

The key part of this, of course, is Mike Yates. It is Mike who gets the plot with any motion, becoming a traitor to UNIT. All reports of how this plot point was developed say that it was a response to his being mind controlled into betraying UNIT in The Green Death. But this isn’t actually pointed to in any active way. There’s no discussion of Mike’s trauma or sense that he’s had it rough recently. Hulke fills in a little bit of this in the novelization, suggesting actively that Yates has been under a lot of strain, but in the actual televised story there’s no real accounting for why he becomes a traitor. He simply does, largely because he sort of has already.

One school of thought, favored by people like Philip Sandifer who view Doctor Who as essentially a progress narrative, is that this marks the beginning of character development as a thing in Doctor Who. And maybe it does—certainly there are other green shoots of this in the vicinity of the Pertwee era, such as Jo’s developing hypnosis resistance in Frontier in Space. And there’s a fair case to be made for character development from here to Planet of the Spiders where Mike redeems himself after his betrayal here. But the betrayal itself is unmotivated, even if they take advantage of it down the road.

No, a more accurate assessment is that Mike Yates turns traitor simply to wring some emotion out of the audience’s assumed investment in UNIT. Yates is a sensible choice for this, with the Brigadier being unthinkable and Benton being too square-jawed and, for that matter, beloved by female viewers. Yates, on the other hand, has always been hobbled by Richard Franklin’s performance, which leaves him as a character familiar enough to audiences to make his betrayal seem big, but in no way beloved enough to make it upsetting. It is, in other words, still basically rooted in a sense of the era’s nostalgia for itself.

But even as the production begins to buy its own hype and eat its own tail, Hulke retains a bracing suspicion of nostalgia. The specific goal of the evil leftists is to turn back time to before civilization ruined it so they can try again—a project called Operation Golden Age. The key scene on this front is the Doctor’s confrontation with Mike Yates (which, in fitting with the lack of actual arc around his betrayal, never actually gets to a point where the Doctor changes Mike’s mind), which contains the story’s best known line, the Doctor’s adage that “there never was a golden age.” This is framed in broader terms, as a commentary on a political tendency, but it is difficult not to read it as an aesthetic barb as well.

The commonality between these two strands is straightforward: in neither case is Hulke offering any sort of positive alternative. Just as there is no visible option for fixing the pollution of the world beyond the corrupt and maniacal leftists, there is no forward vision in amidst the rejection of nostalgia. Invasion of the Dinosaurs, in all regards, comes to a dead end and stops.

It is worth, then, reflecting on the Pertwee era. As we have noted, the era combines an innate conservatism with a curious and appealing willingness to portray a hostile and antihumanist planet. These instincts are not, of course, incompatible—just ask Nick Land. But one of them, at least, seems basically accurate, while the other seems like the underlying reason why the first is so likely to prove lethal on an upsetting scale. (She writes on the day the first COVID-19 case is confirmed in her county.) Nevertheless, their comorbidity is ultimately a dead end. The notion of a hostile planet, when combined with conservatism, cannot actually go anywhere. The only possible responses to the planet’s murderous indifference are intensely radical. Conservatism, even when pushed into the frenzied and manically reactionary mode of Nick Land, is unable to offer any response other than a grim slouch towards extinction.

The Pertwee era attempts to deny this gravity with an incandescent burst of glam aesthetics and an outward gaze, both in the now discredited notion that there’s any future in space and in the quasi-Christian fantasy of extraterrestrial intervention somehow saving humanity. (This is, of course, intensely compatible with glam, being the basic hook of Ziggy Stardust.) But these are both entirely fantasies. Space is so vast and inhospitable as to be an entirely useless future without casual violation of the basic laws of physics. Aliens are not going to come, and if they do the reason to believe they’ll save us instead of being as implacably hostile as the planet are a short list that consists entirely of the statement “I am a naive and blinded utopianist.”

Put another way, the Pertwee era sees Doctor Who make a simultaneous investment in the weird and disinvestment in the notion of change and multiplicity. This combination is perverse, and could ride successfully on that perversity for some time, but as Hulke deftly shows here it is ultimately a dead end, with nothing to show beyond its surface perversity. It would obviously be absurd for me to treat “nihilist” as a pejorative but there’s a hollowness to the way in which this era has nothing to offer but a doomed world and a CSO effect. Nihilism need not be self-absorbed, superficial, and certainly not so unproductive.

We will have plenty of time to discuss how and where Doctor Who turns from here. The discussion of the Pertwee era as largely weird, however, tips my hand at least somewhat, as for that matter does even a cursory knowledge of the forthcoming Hinchcliffe era of the show. The answer, obviously, will not be towards something that is in some sense productive. Its orientation towards the weird or towards the notion of a hostile planet may change, but at the end of the day its conservatism cannot and will not. Nevertheless, there are things to do with the apocalypse besides sit, rapturously consumed by how stylish it is. Hulke, who has himself turned away from any productive vision in favor of becoming a cynical ex-communist, has no sense of what those things might be. But by demanding them, he’s still shown himself to have more foresight than almost anyone else in the room.

March 25, 2020 @ 5:52 am

“This is, of course, intensely compatible with glam, being the basic hook of Ziggy Stardust.) But these are both entirely fantasies” Really?

March 25, 2020 @ 4:36 pm

Another great entry.

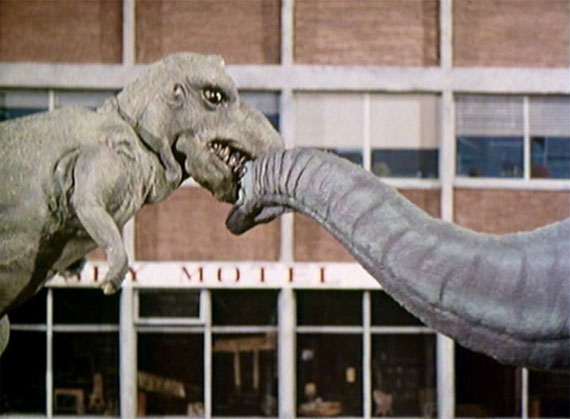

The really important question, though, is: what’s the coolest dinosaur/prehistoric creature in the story, either by prop (for a given definition of cool) or species?

March 29, 2020 @ 5:08 pm

I’ve just asked my 8 year old dinosaur obsessed son who has watched Invasion of the Dinosaurs. His answer was cutting: “None. There’s nothing cool in it. They just look weird”

April 1, 2020 @ 11:35 pm

That’s hilarious – and sadly pretty true. The dinosaurs lack the derpy charm of the Skarasen after them or the Silurian dinosaur before them and seem more like those single-color cheap plastic models that always wound up at the bottom of the dinosaur toy bin in my own childhood.

April 2, 2020 @ 12:38 pm

The funniest thing is that Barry Letts had commissioned the story in the first place because he was approached by a company that said that they could produce very realistic dinosaur models! Perhaps he should have asked for some evidence of the claim.

It’s the first Doctor Who story I have any memory of watching. Watching it on a tiny balck and white TV and my gran and grandad’s house aged 4 back in 1974 it didn’t look too bad!

April 4, 2020 @ 10:00 am

One of the dinosaur models survives and now resides in the dinosaur museum in Dorchester. I visited the museum and the model is actually quite impressive in real life. Maybe it’s because it’s only impressive as a static exhibit, but it just didn’t transfer well to television.

April 5, 2020 @ 11:10 am

Oh yes, I’ve been there too – you’re right, it looks much more impressive than in the show! I’ve got a photo of my son with it somewhere, when he was about 5…

April 5, 2020 @ 12:32 pm

Did you mean Doset? If so I’ve been there as well, but I didn’t spot it. It’s a funny little place , rammed full of stuff – obviously one man’s personal passion.

March 25, 2020 @ 7:19 pm

I’d never thought of the baddies in this story being left-wing. They all seem like archetypal conservatives. Not so much the people on the spaceship, but the politician and the general, harking back to a golden age? Complete tories.

March 28, 2020 @ 12:10 pm

Yes, I’d agree with this, although I would include the people on the spaceship. I think Hulke is critiquing people who think they’re left wing, but are actually anything but. Their objective is the ultimate middle-class utopia.

March 29, 2020 @ 5:04 pm

I heard someone, probably on the DVD extras , saying that it was meant as a critique of the hard right consevatives who wanted to return to the “good old days”. At the time it was widely thought that Britain might be heading for a coup by the army with the support of the right wing of the Conservative Party. That seems to fit with the fact that those organising the conspiracy seem to be thoroughly establishment figures.

That said, I thought this theory about the story might be wishful thinking. You can’t ignore the enviromentalist motivation. I wonder if Hulke, with his involvement in the Communist Party, might see Conservatives and enviromentalists as two sides of the same coin.

March 31, 2020 @ 10:24 pm

“The specific goal of the evil leftists is to turn back time to before civilization ruined it so they can try again—a project called Operation Golden Age”

It’s almost certainly complete coincidence, but I’ve just re-watched the Origins of Doctor Who extra on the Edge of Destruction DVD, and when they were first creating the character of the Doctor, that was going to be his secret motivation – he’d fled/escaped from the future and was searching for an ‘ideal past’. Once he’d found it, he planned to somehow destroy the future. Mr Newman vetoed that one pretty sharpish …

April 5, 2020 @ 11:12 am

It’s been a while since there’s been a post – I hope you and yours are keeping safe and well, El.