Chapter Three: The Unique Details and Methods of a Crime (The Judge of All The Earth)

Part of the difficulty in tracking the fallout of Moore’s split with DC is simply that it’s so extensive. Once the rupture began it spread quickly, fueled in no small part by Alan Moore’s tendency to, as he’s put it, burn his bridges when reacting against something so as to make sure he’s never tempted to go second guess himself. But in this case the fractal repetition of Moore’s grievances with DC have served to make the initial issues harder to see, to the point where the standard wisdom is that Moore’s break with DC came over a dispute in the handling of the Watchmen trade paperback when, in reality, he had made his decision not to accept any new work from DC in January of 1987, eight months before the trade paperback even came out, and five months before Moore was actually done working on it. This decision came during a wider dispute about DC’s proposed creation of a ratings system for their comics. And even that point is not a single discrete cause that can be separated out from all of the others and identified as the original, true rift, but at best the third issue to arise between Moore and DC in quick succession.

Part of the difficulty in tracking the fallout of Moore’s split with DC is simply that it’s so extensive. Once the rupture began it spread quickly, fueled in no small part by Alan Moore’s tendency to, as he’s put it, burn his bridges when reacting against something so as to make sure he’s never tempted to go second guess himself. But in this case the fractal repetition of Moore’s grievances with DC have served to make the initial issues harder to see, to the point where the standard wisdom is that Moore’s break with DC came over a dispute in the handling of the Watchmen trade paperback when, in reality, he had made his decision not to accept any new work from DC in January of 1987, eight months before the trade paperback even came out, and five months before Moore was actually done working on it. This decision came during a wider dispute about DC’s proposed creation of a ratings system for their comics. And even that point is not a single discrete cause that can be separated out from all of the others and identified as the original, true rift, but at best the third issue to arise between Moore and DC in quick succession.

There are of course two ways to look at this. In one, the subsequent retellings of the dispute on both sides have thoroughly muddied the waters such that the original dispute over comics ratings has been obscured. And there’s a degree of truth to this – the latter focus on the rights to Watchmen and DC’s broader exploitation of the property has largely eclipsed what was a real and acrimonious dispute in the early months of 1987. In the other, however, it is the wider perspective that looks at the full extent of Moore’s myriad of grievances that is more accurate, even about the initial dispute. In this view, just because the rating’s system was the straw that broke the camel’s back doesn’t mean that the bale of hay as a whole wasn’t the cause. And this view has a wider support within Moore’s career, which by the start of 1987 was already characterized by a string of disputes with his publishers. Indeed, by the time Watchmen started Moore had already broken with all of his UK publishers, although his departure from IPC had not yet taken on the tone of finality that his rifts with Marvel UK and Dez Skinn had. Indeed, if one wanted to be unsympathetic to Moore – and it’s worth stressing that there are no shortage of people who are very much invested in being more or less completely unsympathetic to Alan Moore – one could suggest that getting into fights with his publishers was simply what he did, and that he was, consciously or unconsciously, just looking for a reason to get mad at DC.

Certainly Moore would have had little reason to see DC as essential to his career. He had, after all, succeeded with essentially every company he’d worked with. More to the point, he was by this point in the enviable position of being a creator who was a draw in his own right, with an audience that would follow him across projects and companies. While he could not afford to alienate every publisher in comics, the reality was that his career could and would survive alienating any given publisher. Indeed, a fair case can be made that splitting ways with DC was a savvy career move on Moore’s part, although arguing that he thought of it as such requires assuming a level of ruthless careerism that is difficult to square away with details like the fact that he seemingly never actually read the Watchmen contract before signing it.

Certainly Moore would have had little reason to see DC as essential to his career. He had, after all, succeeded with essentially every company he’d worked with. More to the point, he was by this point in the enviable position of being a creator who was a draw in his own right, with an audience that would follow him across projects and companies. While he could not afford to alienate every publisher in comics, the reality was that his career could and would survive alienating any given publisher. Indeed, a fair case can be made that splitting ways with DC was a savvy career move on Moore’s part, although arguing that he thought of it as such requires assuming a level of ruthless careerism that is difficult to square away with details like the fact that he seemingly never actually read the Watchmen contract before signing it.

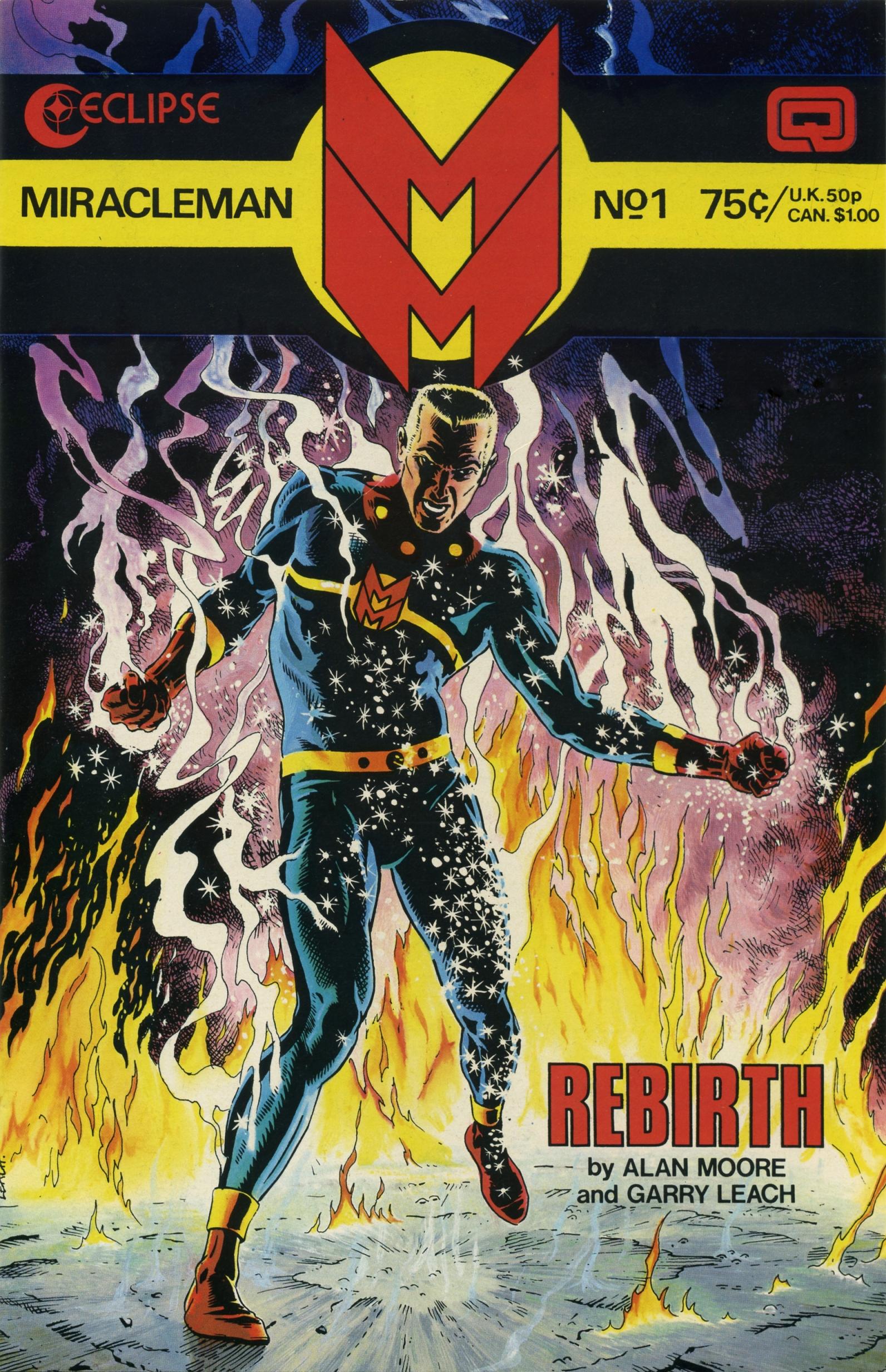

Much of this hinges on the practical differences between the US and UK comic industries. As has been previously noted, for the most part the UK was dominated by IPC (publisher of 2000 AD, among others) and D.C. Thomson (publisher of The Beano and The Dandy, as well as Starblazer), but the relatively small size of the market meant that even smaller players like Marvel UK and Quality had significant visibility such that Moore, by publishing simultaneously in Warrior, The Daredevils, and 2000 AD, was visibly a figure who existed outside the purview of any given company, especially once he emerged as a personality in his own right. But the US, despite being a much larger market, was, by 1986, very much a two company market. Smaller publishers existed – indeed, Moore was working with Eclipse, First Comics, and Fantagraphics in the US by the time Watchmen started. But the degree to which Marvel and DC dominated the market was much greater than the degree to which IPC and D.C. Thomson did. And with Moore unwilling to work with Marvel following Jim Shooter’s hardline stance against Eclipse using the Marvelman name, Moore was in much greater danger of looking like a company man in the US market than he ever had been in the UK.

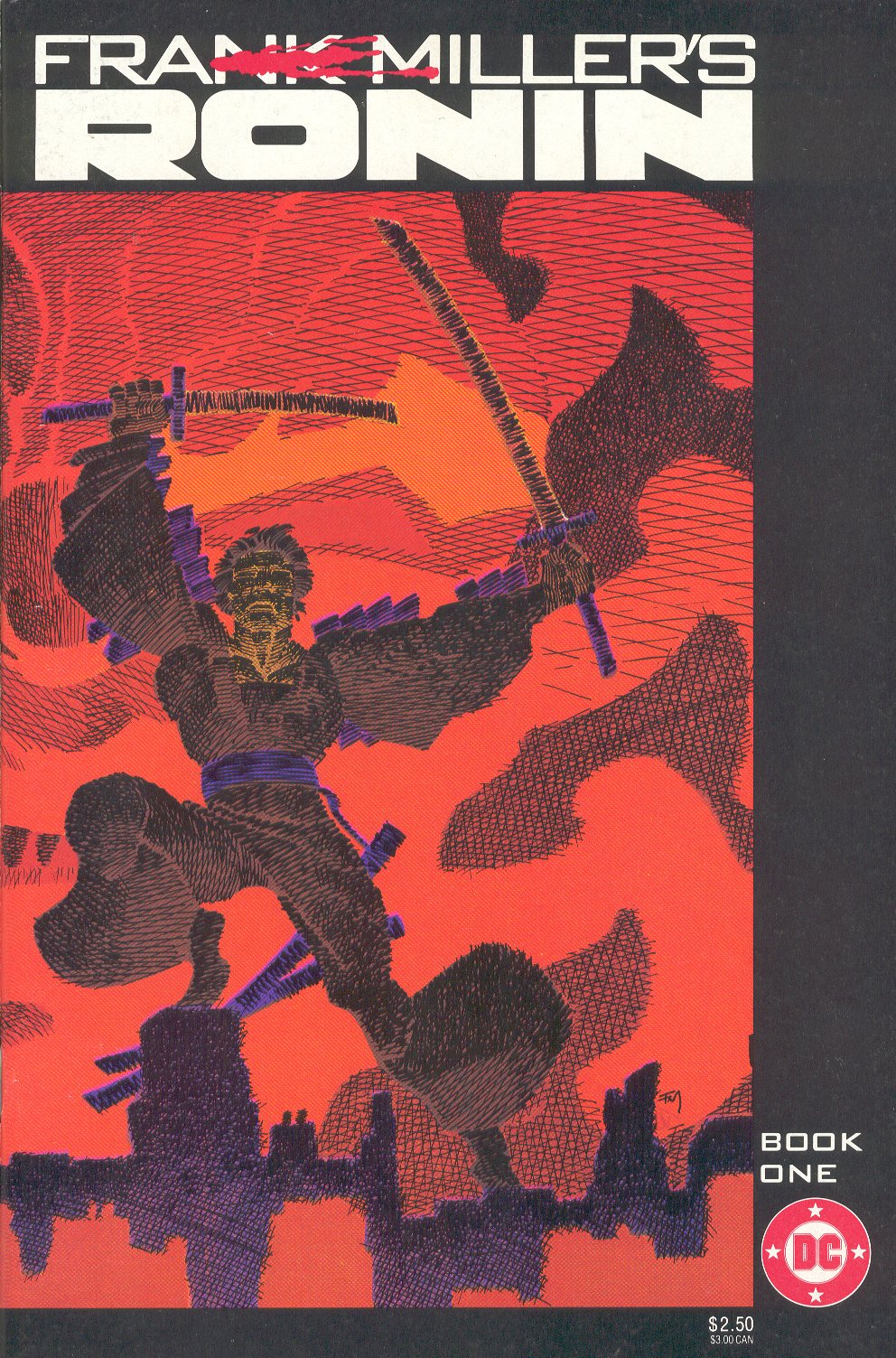

But if Moore was, consciously or unconsciously, looking for a reason to walk away from DC, it’s just as true that DC was looking for a reason to push Moore towards the exit. Certainly they seem to have done little to try to keep him on board. It’s instructive to compare Moore’s later treatment by DC with the way the company handled things with Neil Gaiman a decade later as he finished work on Sandman. Despite the fact that nobody was under any illusions that any of the Sandman characters were creator-owned (in contrast with Watchmen) and that DC was perfectly entitled to simply continue the series without him, DC agreed end the title, not to use the main characters elsewhere without Gaiman’s express approval, and to consult him on the use of the characters in general, and were generally happy to allow Gaiman to renegotiate earlier deals on more favorable terms in order to keep him on-board and generally happy with the company. Similarly, not long before their dispute with Moore, DC agreed to a revision to Frank Miller’s contract for Ronin. With Moore, however, DC have spent decades antagonizing him further, often seeming to go out of their ways to find new ways of snubbing him.

For all that Moore was a source of financial success for them, it is not hard to see why DC might react poorly to him. DC was at its heart a fundamentally conservative company. Moore, in the 80s, may not have been a snake-worshipping occultist yet, but he was still a psychedelic anarchist with a furiously revolutionary working class sensibility. To DC, an obedient and dutiful subsidiary of corporate giant Warner Communications, this attitude would have been downright alarming. Simply put, to DC Moore was an erratic and unpredictable figure whose creator-centric vision of what the comics industry should be was actively threatening. At best, they were better off without him; at worst, he was someone to make an example of so that creators, most of whom were not nearly as big a draw as him, would know their place and not get any lofty ideas.

For all that Moore was a source of financial success for them, it is not hard to see why DC might react poorly to him. DC was at its heart a fundamentally conservative company. Moore, in the 80s, may not have been a snake-worshipping occultist yet, but he was still a psychedelic anarchist with a furiously revolutionary working class sensibility. To DC, an obedient and dutiful subsidiary of corporate giant Warner Communications, this attitude would have been downright alarming. Simply put, to DC Moore was an erratic and unpredictable figure whose creator-centric vision of what the comics industry should be was actively threatening. At best, they were better off without him; at worst, he was someone to make an example of so that creators, most of whom were not nearly as big a draw as him, would know their place and not get any lofty ideas.

All the same, it’s easy to be taken aback by the pettiness of DC at times. A fairly instructive example comes in the form of Paul Levitz, who worked at DC for decades, eventually rising to publisher within the company. It was Levitz, then a vice-president, who greeted Moore on his first American visit by calling him his “greatest mistake,” a line Moore notes that he found strange at the time and downright ominous in hindsight. But in some ways more remarkable is the axe-grinding Levitz engaged in within his post-DC coffee table book 75 Years of DC Comics: The Art of Modern Mythmaking when coming to the subject of Moore’s work for DC. In Levitz’s telling, “a steady stream of talented people were attracted to DC by the longer story lengths, better reproduction, and creative opportunities. Among them was Alan Moore, a soft-spoken magician with a broad range of arcane interests.” Several things here are distinctly unfair – the suggestion, for instance, that Moore came to DC like some old world pilgrim seeking a better life, when in fact DC had deliberately sought him out. Similarly, although it’s true that Moore was not the first UK creator to be hired by DC, the suggestion that he was part and parcel of the wave of creators as opposed to the first time DC poached a writer from 2000 AD as opposed to an artist is thoroughly unfair. But perhaps strangest is the decision to suggest that Moore was a magician when he was hired, a revision that seems mainly to sensationalize Moore as an eccentric nutter whether or not it’s relevant to the point. (More gallingly, the book later describes him as a “stage magician.”) Even pettier is Levitz’s musing that “Watchmen would not have continued to achieve such recognition” were it not for DC’s invention of the trade paperback, presented by Levitz as a bold capstone to a decade of DC’s experimenting with publication forms. This is, to say the least, a bit rich; while it’s true Watchmen was one of the first DC titles to get a trade collection, it is not as though collecting a serialized work after it’s finished is an unprecedented idea in publishing. Certainly it’s ridiculous to imply, as Levitz does, that this is on par with Moore and Gibbons’s work on the comic itself. And this is made doubly galling by the fact that the trade paperback format Levitz is boasting of having invented is the precise means by which Moore claims they kept the rights from reverting to him.

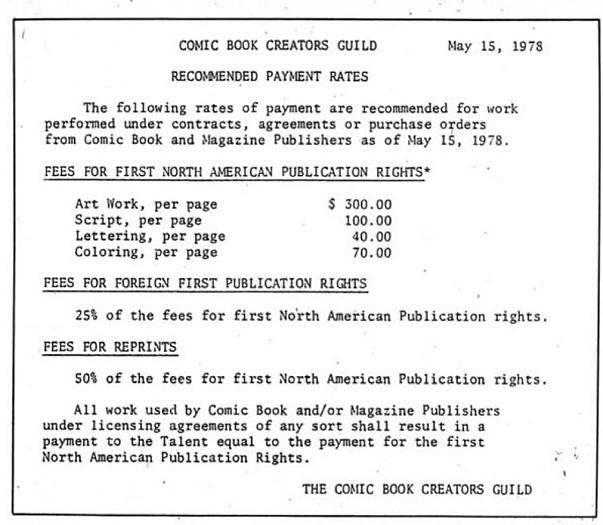

In some ways, what’s most striking about this pettiness is that Levitz was, in most regards, relatively progressive in terms of creators rights at DC. He was, for instance, diligent in making sure that the creators who originated various minor concepts that made their way into movies like particular vehicle designs or small details of a given telling of Batman’s origin were compensated when the movies came out, and is widely credited with preventing anything like Before Watchmen happening for as long as he was still at the company. But Levitz’s relationship with creator rights has always been complex. In 1978 he spoke to The Comics Journal about Neal Adams’s efforts to form an ad hoc union called the Comics Creators Guild, saying that while he “would dearly love to see a Guild formed in the interests of working comics freelancers” he viewed the actual effort to make one as nothing more than “a group of people who don’t work in the industry working for a set of idealistic goals without regard to the real interests of freelancers,” and speaking at the first meeting regarding the guild mainly to complain that the rates Neal Adams was suggesting creators should make were unrealistic because Marvel and DC weren’t making enough money to pay them. All of which is to say that Levitz has been consistent, throughout his career, in a belief that what’s good for the massive comics publisher is good for the freelancer.

What’s perhaps odd is that Moore did not, at least at first, really differ from that belief. Indeed, the way in which Moore describes his falling out with the company is telling: “I was starting to realize that DC weren’t necessarily my friends.” Because it’s crucial to realize, Moore really did think they were. That’s the entire reason he never actually read the Watchmen contract: he trusted the people handing it to him had his best interests at heart. This was, of course, many things; hopelessly naive, for one. An almost inevitable extension of his honor among thieves approach to creating art, for another. But, perhaps most crucially, it was more or less how people like Paul Levitz were encouraging him to think. And so when Levitz subsequently got into a dispute with Moore and Gibbons shortly after Watchmen launched over whether or not they deserved royalties on the replica bloodstained yellow smiley badges that were being widely sold in comic shops (a dispute that was over, at most, a couple thousand dollars) and made a grand show of agreeing to a royalty without conceding the legal point by which DC had originally argued the badges, despite being sold in comic shops, were “promotional items,” Moore was understandably rattled, minor as the issue was. And when, later in 1986, Jeanette Kahn had lunch with Moore and Gibbons and made an off-handed comment about doing some Watchmen prequels and how “of course we wouldn’t do this if you were still working for us,” Moore was once again rattled by what he took as a threat. Indeed, as Moore put it when describing the incident in an interview four years later, “I really, really, really don’t respond well to being threatened. I couldn’t tolerate anyone threatening me on the street; I couldn’t tolerate anyone threatening me in any other situation in my life. I can’t tolerate anyone threatening em about my art and my career and stuff that’s as important to me as that. That was the emotional breaking point. At that point there was no longer any possibility of me working for DC in any way, shape, or form.”

What’s perhaps odd is that Moore did not, at least at first, really differ from that belief. Indeed, the way in which Moore describes his falling out with the company is telling: “I was starting to realize that DC weren’t necessarily my friends.” Because it’s crucial to realize, Moore really did think they were. That’s the entire reason he never actually read the Watchmen contract: he trusted the people handing it to him had his best interests at heart. This was, of course, many things; hopelessly naive, for one. An almost inevitable extension of his honor among thieves approach to creating art, for another. But, perhaps most crucially, it was more or less how people like Paul Levitz were encouraging him to think. And so when Levitz subsequently got into a dispute with Moore and Gibbons shortly after Watchmen launched over whether or not they deserved royalties on the replica bloodstained yellow smiley badges that were being widely sold in comic shops (a dispute that was over, at most, a couple thousand dollars) and made a grand show of agreeing to a royalty without conceding the legal point by which DC had originally argued the badges, despite being sold in comic shops, were “promotional items,” Moore was understandably rattled, minor as the issue was. And when, later in 1986, Jeanette Kahn had lunch with Moore and Gibbons and made an off-handed comment about doing some Watchmen prequels and how “of course we wouldn’t do this if you were still working for us,” Moore was once again rattled by what he took as a threat. Indeed, as Moore put it when describing the incident in an interview four years later, “I really, really, really don’t respond well to being threatened. I couldn’t tolerate anyone threatening me on the street; I couldn’t tolerate anyone threatening me in any other situation in my life. I can’t tolerate anyone threatening em about my art and my career and stuff that’s as important to me as that. That was the emotional breaking point. At that point there was no longer any possibility of me working for DC in any way, shape, or form.”

Although it may well have been Moore’s breaking point, this was, as mentioned, still not quite the moment he decided to walk away from DC. But it’s a striking incident all the same, less for what it reveals about Moore (whose response was on the whole what you’d expect from him) but rather what it reveals about DC. The fact that Kahn remarked on how Moore’s willingness to work for them might impact their publishing plans is, after all, fairly compelling evidence that DC was already aware that they might be losing Moore as of 1986, despite the fact that at this point the only actual dispute between the two had been over the Watchmen buttons.

As mentioned, some of this was simply that Moore had never shown any indication of being a one-company man. But more than that was the sort of work Moore was expressing an interest in. For one thing, Moore was increasingly invested in the idea of creator ownership, a working arrangement he’d first experienced with Dez Skinn’s Quality Comics at the dawn of his career, and continued to enjoy with Miracleman at Eclipse. This was in marked contrast with DC’s way of doing business, and indeed had been something of a sticking point in negotiating the contract for Watchmen; at a panel at the 1985 San Diego Comicon, Moore explained that the initial version of the Watchmen contract was a work for hire contract, but that he and Gibbons had asked for a creator-owned contract, which DC agreed to, offering a contract where, as Moore explained it, “DC owns it for the time they’re publishing it, and then it reverts to Dave and me, so we can make all the money from the Slurpee cups.” This, of course, proved not to be quite so simple, but it’s worth noting that even this arrangement was unusually deferential to creators for DC. Creator ownership simply wasn’t something they did. Their business model was based on the continual marketing of long-running characters, which necessarily involved owning them.

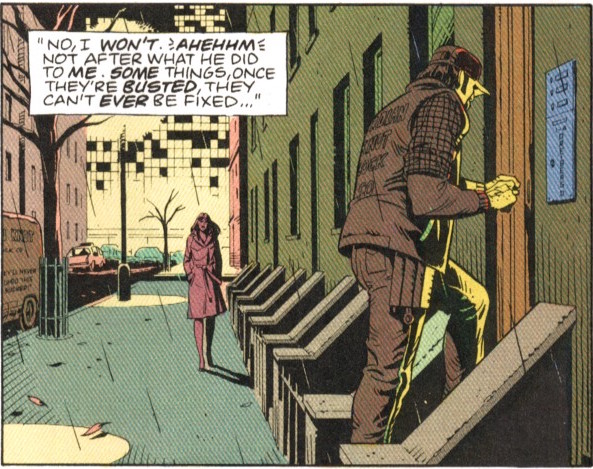

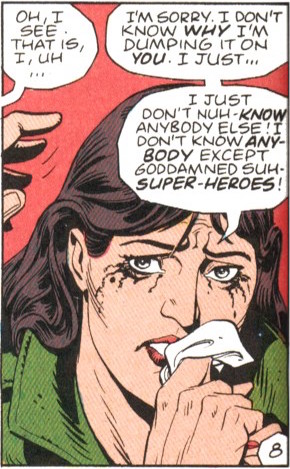

On top of that, Moore was clearly itching to do work beyond superheroes. While his discussion of this in the intro to the initial collected version of Watchmen, where he talks about having lost his nostalgia for the superhero and being more interested in “the ordinary, non-telepathic, unmutated and slightless humanoids hanging out on their anonymous street corner” within Watchmen than in its protagonists, has to be taken the context of Moore’s having split with DC at that point, it was a sentiment he’d expressed three years earlier at the aforementioned Comicon panel. But more telling was the context – as a lead-in to Moore announcing some (ultimately never completed) work for Fantagraphics, the alternative comix-minded publishers of The Comics Journal (who ran a transcript of the panel a few months later) that suited his investment in creator ownership to boot. Put another way, even before Watchmen came out, Moore was clearly eyeing a degree of up-market respectability that DC’s near exclusive focus on superheroes just wasn’t compatible with.

On top of that, Moore was clearly itching to do work beyond superheroes. While his discussion of this in the intro to the initial collected version of Watchmen, where he talks about having lost his nostalgia for the superhero and being more interested in “the ordinary, non-telepathic, unmutated and slightless humanoids hanging out on their anonymous street corner” within Watchmen than in its protagonists, has to be taken the context of Moore’s having split with DC at that point, it was a sentiment he’d expressed three years earlier at the aforementioned Comicon panel. But more telling was the context – as a lead-in to Moore announcing some (ultimately never completed) work for Fantagraphics, the alternative comix-minded publishers of The Comics Journal (who ran a transcript of the panel a few months later) that suited his investment in creator ownership to boot. Put another way, even before Watchmen came out, Moore was clearly eyeing a degree of up-market respectability that DC’s near exclusive focus on superheroes just wasn’t compatible with.

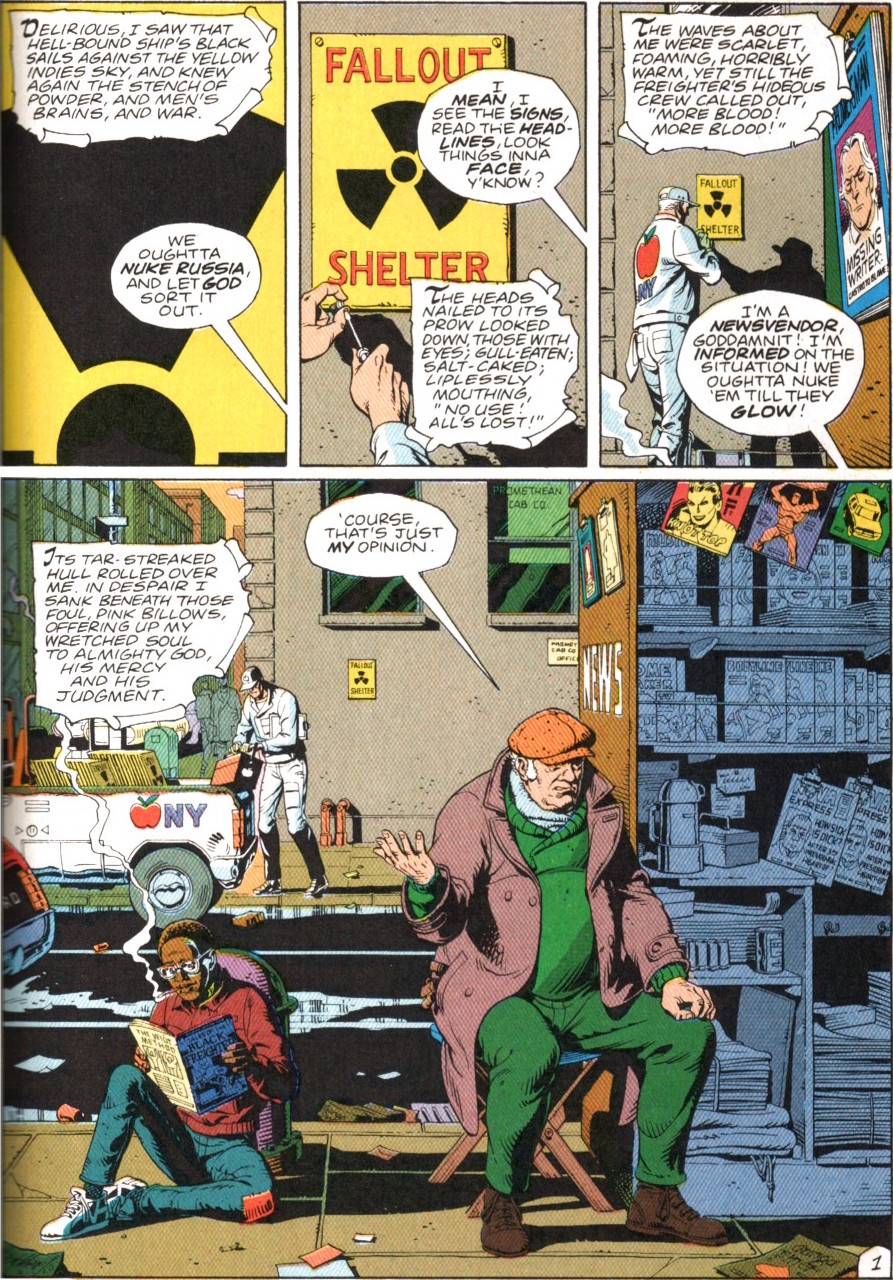

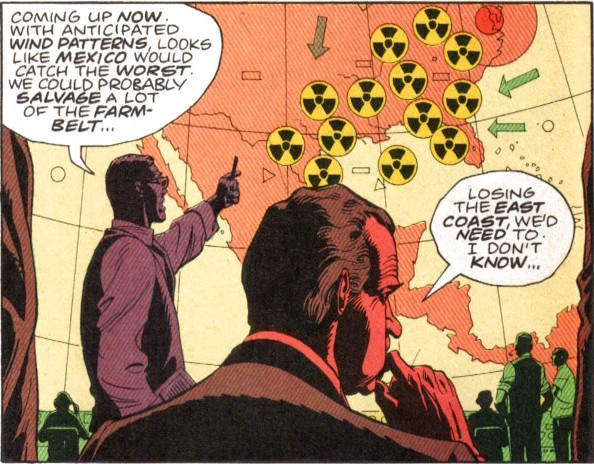

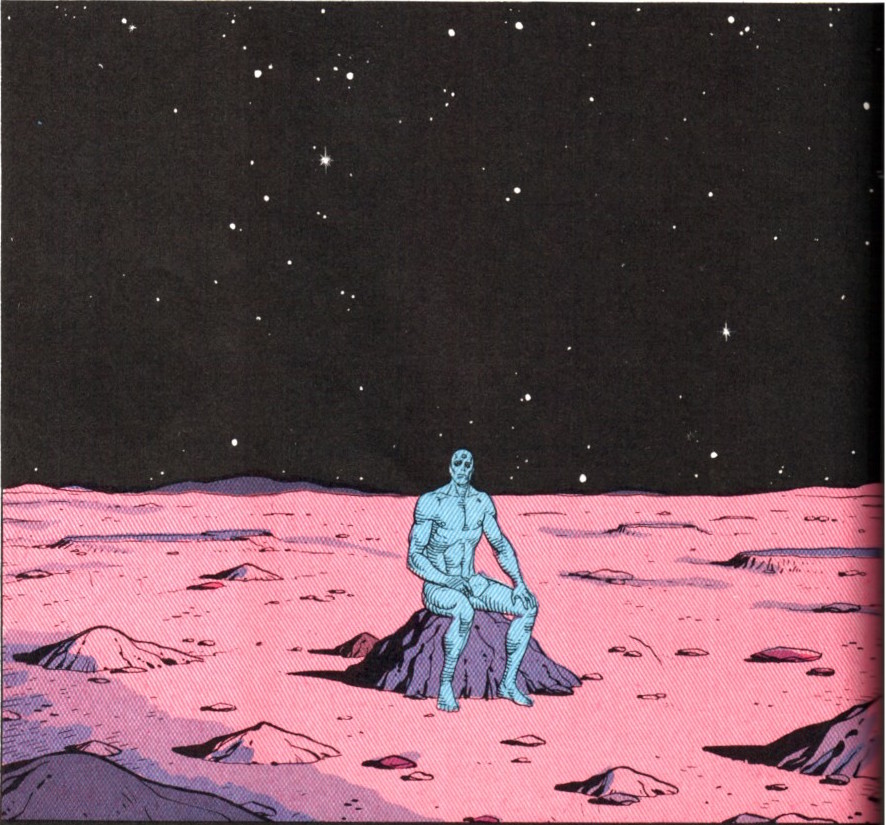

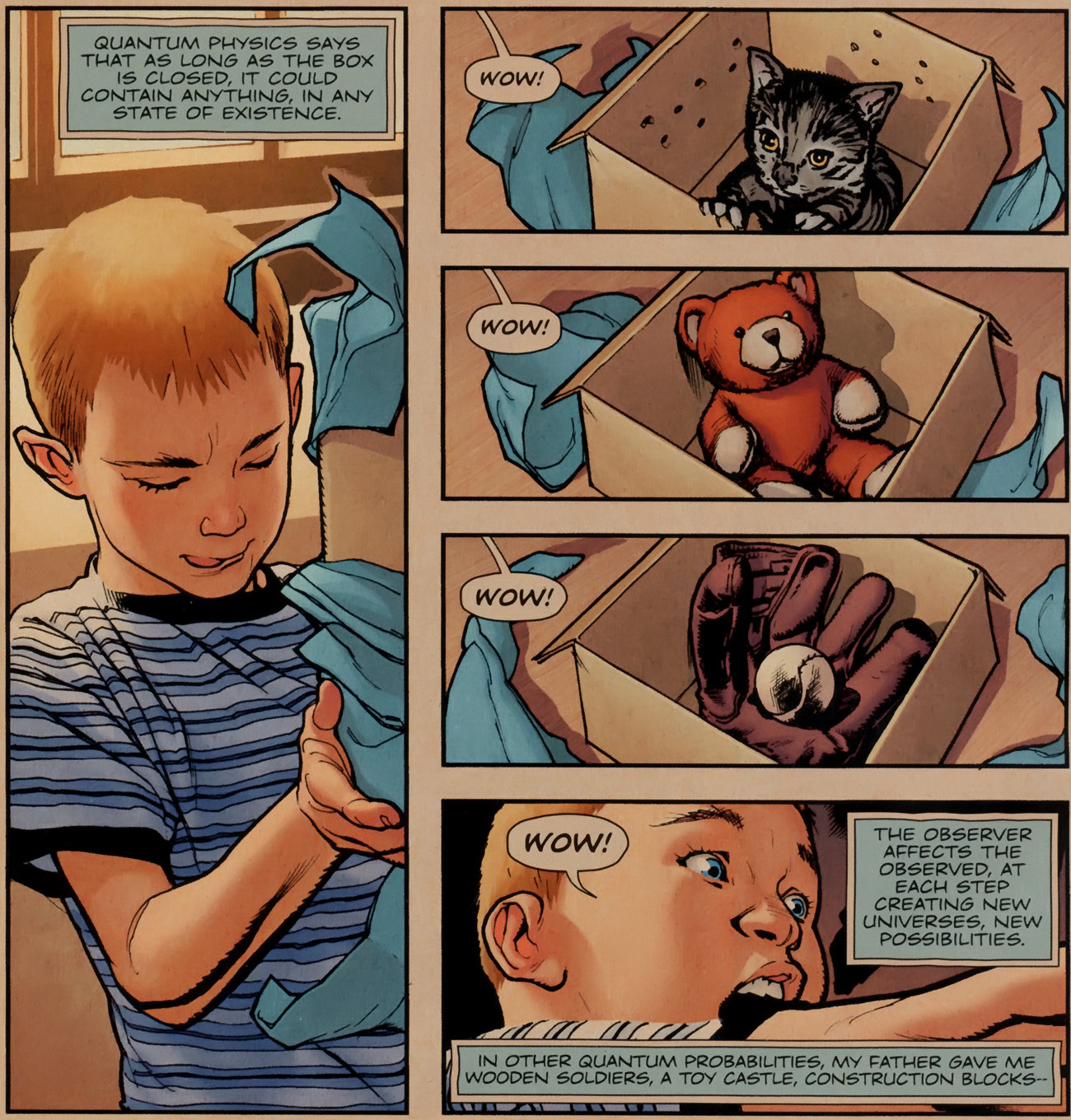

More even than that, however, Moore was interested in exploring comics as a literary form, a process that really kicked off with the third issue of Watchmen, which Moore, in several interviews, cites as a turning point for the project. As he puts it in one interview, “it was with the very first page of #3 when I’d realized we’d actually gotten more than we bargained for. I suddenly thought, “Hey, I can do something here where I’ve got this radiation sign being screwed on the wall on the other side of the street, which will underline the kind of nuclear threat; and I can have this newspaper guy just ranting, the way that people on street corners with a lot of spare time sometimes do; and I can have the narrative from this pirate comic that the kid’s reading; and I can have them all bouncing off each other; and I can get this really weird thing going where things that are mentioned in the pirate story seem to relate to images in the panel, or to what the newsman is saying… And that’s when Watchmen took off; that’s when I realized that there was something more important going on than just a darker take on the super-hero, which after all, I’d done before with Marvelman.”

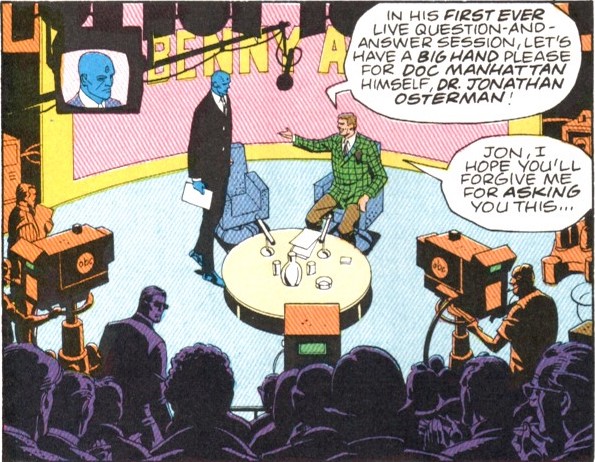

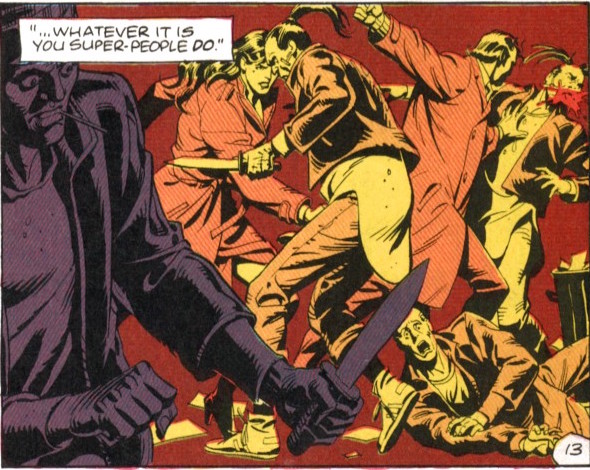

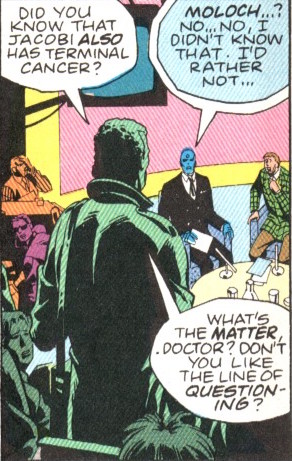

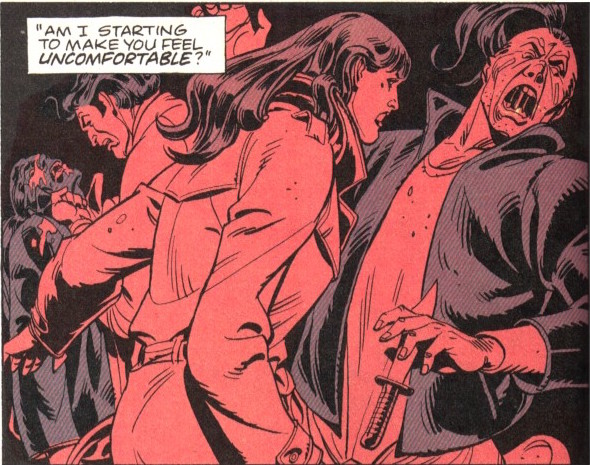

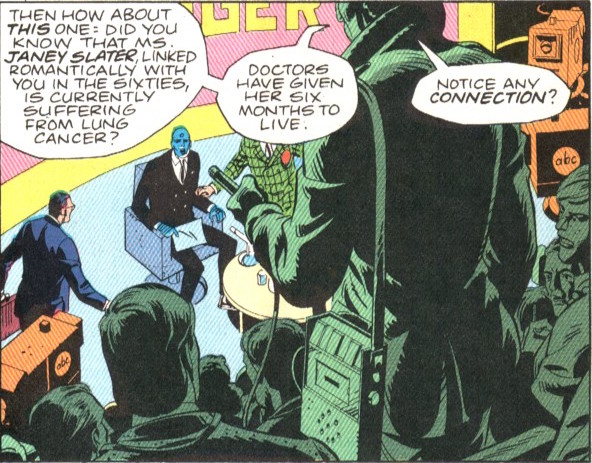

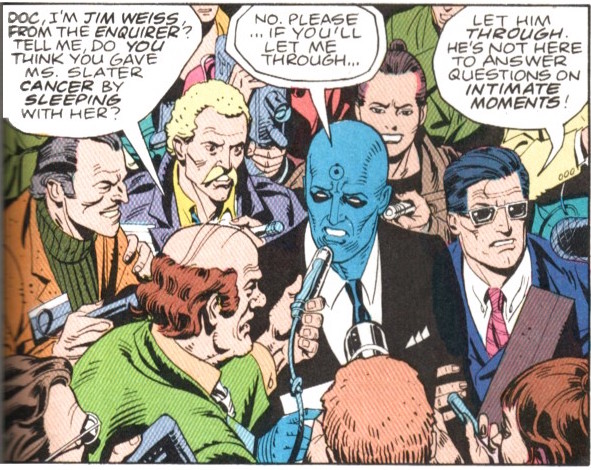

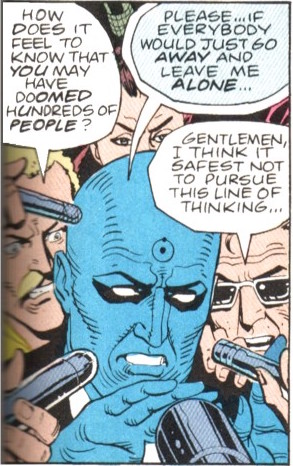

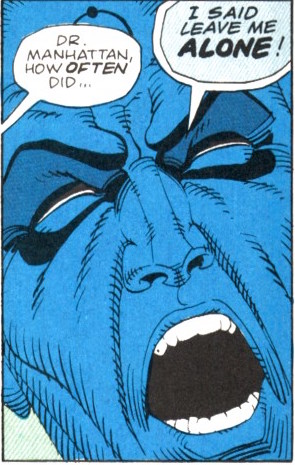

It is true that the third issue is where one of the book’s signature techniques really comes into focus, and the first page is illustrative in that regard. It’s not that Moore hadn’t done juxtapositions along these lines before; indeed, in the first issue he paralleled several remarks from the detectives investigating Edward Blake’s murder with flashbacks to that murder, most notably with the grim juxtaposition of Blake being hurled out the window with the elevator operator in the building saying, “ground floor comin’ up.” But he’d never really engaged in the sort of extended and complexly intertwined sequences. The first panel of Watchmen #3, for instance, features a close-up of a sign for a fall-out shelter, black radiation symbol on a yellow background. Overlaid is the caption from the Tales of the Black Freighter comic Bernie is reading: “Delerious, I saw that hell-bound ship’s black sails against the yellow Indies sky, and knew again the stench of powder and men’s brains, and war,” a description that serves to describe the sign as well. Meanwhile, Bernard, the news vendor, proclaims that “we oughta nuke Russia, and let God sort it out,” which remarks both upon the radiation sign and upon the text from the comic. And the scene continues in a similar manner – the second panel, for instance, has Bernard talking about how “I see the signs, read the head-lines, look things inna face, y’know” as the fallout shelter sign is shown from further out and the Tales of the Black Freighter comic continues, “the heads nailed to its prow looked down, those with eyes; gull-eaten; salt-caked; liplessly mouthing, ‘no use! All’s lost!’”

The issue’s biggest set piece, however, is a six-page sequence in which a television interview with Doctor Manhattan is paralleled with Dan and Laurie fighting a group of muggers in an alley. Each of the six pages is six panels long, with one panel in each row double-width – the right-most panel on the top and bottom, and the left-most on the middle. Doctor Manhattan’s strand of narrative occupies the left three panels, Laurie and Dan’s the right. The actual text, at least for the first four pages, all comes from Doctor Manhattan’s scene, however, with stray phrases overlapping events in the alley. So, for instance, when a journalist asks Doctor Manhattan, “I wonder if you remember Wally Weaver. Back int he early sixties, the newspapers called him ‘Dr. Manhattan’s Buddy.’ He died of cancer in 1971. I believe it was sudden and quite painful,” the last sentence is overlaid with Dan punching a criminal in the face, blood splattering outwards. And when the journalist subsequently asks “what’s the matter, Doctor? Don’t you like this line of questioning? Am I starting to make you feel uncomfortable?” the last question is juxtaposed with Laurie punching a mugger in the crotch. Again, what’s interesting is not even the individual parallels but rather the extended use of a rigid structure and the way in which the two scenes keep dovetailing – all told, there are twelve separate lines of dialogue from the interview that get paralleled meaningfully with the fight scene, and then, on the last page, two lines of dialogue exchange between Dan and Laurie that parallel with events surrounding Doctor Manhattan.

It is not, obviously, that DC objected to the high-mindedly literary nature of Watchmen. Rather, it is that they were completely indifferent to it. It was simply not an aspect of the comic they cared about. The grim and “realistic” tone of it was something they could sell, on much the same grounds that they sold Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. But DC’s sense, perhaps understandably, was that the bulk of people buying Firestorm the Nuclear Man, Hawkman, and Legion of Super-Heroes every month were not hugely invested in the literary merit of their purchases. But this disparity in focus was another fundamental source of tension between Moore and DC. Moore might have joked about making money from the Slurpee cups, but at the same panel he talked about why he intended Watchmen to end with the twelfth issue, saying that “we could probably make a lot of money by carrying it on, but I’d rather do something good than something that will make me rich,” and talking about how “you can’t put a price upon reputation.” Whereas DC’s approach, or at least the approach of their marketing department (which held plenty of sway) was to charge double for the issues, start selling the previously free promotional buttons, flood the market with memorabilia, and push for as many prequel and sequel series as they could (which, on Moore and Gibbons’ insistence, was, for many years, zero). All of which combined to make it abundantly clear to all parties that Moore and DC were headed for a collision. What was perhaps less clear to each party was the degree to which this collision would serve as a trap.

It is not, obviously, that DC objected to the high-mindedly literary nature of Watchmen. Rather, it is that they were completely indifferent to it. It was simply not an aspect of the comic they cared about. The grim and “realistic” tone of it was something they could sell, on much the same grounds that they sold Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. But DC’s sense, perhaps understandably, was that the bulk of people buying Firestorm the Nuclear Man, Hawkman, and Legion of Super-Heroes every month were not hugely invested in the literary merit of their purchases. But this disparity in focus was another fundamental source of tension between Moore and DC. Moore might have joked about making money from the Slurpee cups, but at the same panel he talked about why he intended Watchmen to end with the twelfth issue, saying that “we could probably make a lot of money by carrying it on, but I’d rather do something good than something that will make me rich,” and talking about how “you can’t put a price upon reputation.” Whereas DC’s approach, or at least the approach of their marketing department (which held plenty of sway) was to charge double for the issues, start selling the previously free promotional buttons, flood the market with memorabilia, and push for as many prequel and sequel series as they could (which, on Moore and Gibbons’ insistence, was, for many years, zero). All of which combined to make it abundantly clear to all parties that Moore and DC were headed for a collision. What was perhaps less clear to each party was the degree to which this collision would serve as a trap.

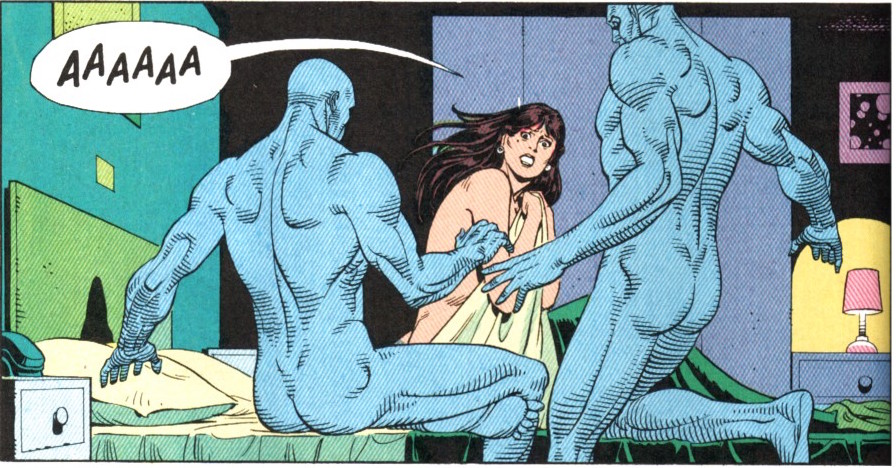

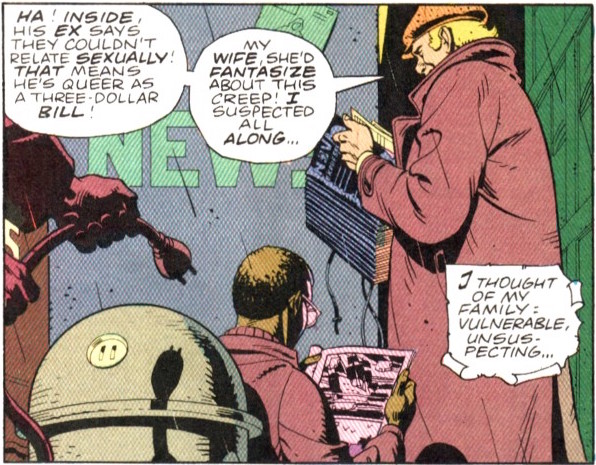

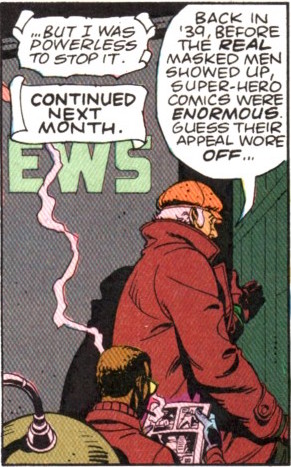

The events that would spark the official rupture between Moore and DC essentially began on October 20th and 21st, 1986, between the publication of Watchmen #5 and #6, when Washington DC CBS affiliate WUSA aired a two-part report on the subject of “sick comics.” The first part had been a fairly standard entrant into the “zap pow comics aren’t for kids” subgenre with a particularly moral panic-like tone. It featured a reporter earnestly describing the comics of her youth, featuring “heroes, strong and brave” who were “cute” and “colorful” but warning that now there existed “a group of anti-heroes” who “have cropped up in comic books intended for older readers.” The report then described Frank Miller and Bill Siencievicz’s miniseries Elektra: Assassin, a typically exuberant Miller action comic, and presented a parent outraged at the fact that her eleven-year-old son was sold a copy of the comic due to one scene which featured naked women. It was a masterpiece of fear-mongering moral panic, complete with a ridiculously coaxing interview with the eleven-year-old (“Were you surprised at the pictures you saw in there?” “Yes.” “What did you see?” “Whole bunch of women on these beds.” “Were the women dressed?” “No.” “What’d you think about that?” “It was crazy.”), but also the sort of filler story that exists merely to wile away the minutes between ad breaks by stoking viewers’ impotent outrage about a basically meaningless issue, which is to say, not something that one normally associates with anything as important as an interdimensional magickal war for the soul of Albion.

The events that would spark the official rupture between Moore and DC essentially began on October 20th and 21st, 1986, between the publication of Watchmen #5 and #6, when Washington DC CBS affiliate WUSA aired a two-part report on the subject of “sick comics.” The first part had been a fairly standard entrant into the “zap pow comics aren’t for kids” subgenre with a particularly moral panic-like tone. It featured a reporter earnestly describing the comics of her youth, featuring “heroes, strong and brave” who were “cute” and “colorful” but warning that now there existed “a group of anti-heroes” who “have cropped up in comic books intended for older readers.” The report then described Frank Miller and Bill Siencievicz’s miniseries Elektra: Assassin, a typically exuberant Miller action comic, and presented a parent outraged at the fact that her eleven-year-old son was sold a copy of the comic due to one scene which featured naked women. It was a masterpiece of fear-mongering moral panic, complete with a ridiculously coaxing interview with the eleven-year-old (“Were you surprised at the pictures you saw in there?” “Yes.” “What did you see?” “Whole bunch of women on these beds.” “Were the women dressed?” “No.” “What’d you think about that?” “It was crazy.”), but also the sort of filler story that exists merely to wile away the minutes between ad breaks by stoking viewers’ impotent outrage about a basically meaningless issue, which is to say, not something that one normally associates with anything as important as an interdimensional magickal war for the soul of Albion.

The second part, on the other hand, was downright fascinating; it focused on efforts within the industry to clean up its act and prevent awful tragedies like eleven-year-old boys accidentally reading something with naked women in it. Which was an astonishing topic in many regards, because there really weren’t any such efforts in progress. Its main interview was Steve Geppi, the president of Diamond Comics Distributors, the largest direct market distributor in the US, who explained that while “there’s a tremendous amount of wholesome comics” on the market, there were also dangerous ones that risked harming children, and vowed, as the reporter put it, “to put pressure on comic book publishers to clean up questionable content.” Geppi spoke emphatically about this as a “moral issue,” explaining that “as you grow up, you’re expected to experience a lot of things in your life. And you’re influenced greatly by your early years in life, and if you’re brought up thinking that violence and sex are so ordinary that you read them in comic books, you become conditioned to that.” Geppi had actively lobbied to be included in the broadcast, and followed it up two days later with a “Special Report” sent to all of the comic book stores with Diamond accounts that opened with Geppi declaring, “personally, I am getting sick and tired of making excuses for irresponsible publishers.”

The second part, on the other hand, was downright fascinating; it focused on efforts within the industry to clean up its act and prevent awful tragedies like eleven-year-old boys accidentally reading something with naked women in it. Which was an astonishing topic in many regards, because there really weren’t any such efforts in progress. Its main interview was Steve Geppi, the president of Diamond Comics Distributors, the largest direct market distributor in the US, who explained that while “there’s a tremendous amount of wholesome comics” on the market, there were also dangerous ones that risked harming children, and vowed, as the reporter put it, “to put pressure on comic book publishers to clean up questionable content.” Geppi spoke emphatically about this as a “moral issue,” explaining that “as you grow up, you’re expected to experience a lot of things in your life. And you’re influenced greatly by your early years in life, and if you’re brought up thinking that violence and sex are so ordinary that you read them in comic books, you become conditioned to that.” Geppi had actively lobbied to be included in the broadcast, and followed it up two days later with a “Special Report” sent to all of the comic book stores with Diamond accounts that opened with Geppi declaring, “personally, I am getting sick and tired of making excuses for irresponsible publishers.”

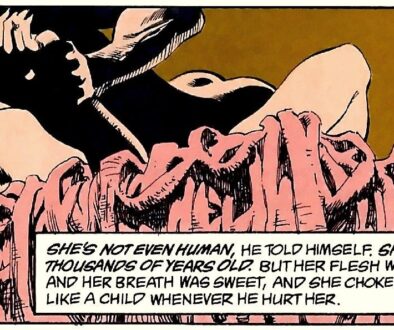

While the “Sick Comics” feature on WUSA had mainly focused on Frank Miller’s Elektra: Assassin, his “Special Report” was unambiguously aimed first and foremost at Alan Moore. In the first paragraph he proclaimed that “Miracleman #9 was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” a strange claim given that it hadn’t appeared in the WUSA report at all. Miracleman #9 is the (in)famous “Birth” issue of the comic, in which Rick Veitch draws an anatomically accurate and head-on depiction of childbirth, and it’s clear that Geppi reacted badly to it. “I have four children of my own ranging from ages six to fifteen,” he writes, “and each of them knows where babies come from. I never found it necessary, however, to graphically describe to them how a baby is born.” He called on publishers to “be much more selective of the nature of the stories and artwork they publish,” and to “do something of a self-regulatory nature, maybe as in the 50s,” a clear reference to the Comics Code Authority. He also noted that if he had known the comic had contained such material he would have “strongly recommend[ed] people don’t buy it.”

While the “Sick Comics” feature on WUSA had mainly focused on Frank Miller’s Elektra: Assassin, his “Special Report” was unambiguously aimed first and foremost at Alan Moore. In the first paragraph he proclaimed that “Miracleman #9 was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” a strange claim given that it hadn’t appeared in the WUSA report at all. Miracleman #9 is the (in)famous “Birth” issue of the comic, in which Rick Veitch draws an anatomically accurate and head-on depiction of childbirth, and it’s clear that Geppi reacted badly to it. “I have four children of my own ranging from ages six to fifteen,” he writes, “and each of them knows where babies come from. I never found it necessary, however, to graphically describe to them how a baby is born.” He called on publishers to “be much more selective of the nature of the stories and artwork they publish,” and to “do something of a self-regulatory nature, maybe as in the 50s,” a clear reference to the Comics Code Authority. He also noted that if he had known the comic had contained such material he would have “strongly recommend[ed] people don’t buy it.”

Geppi’s letter is a fascinating and largely pathological piece. Its most revealing section comes when says, “I can imagine a 13-year-old-girl” who reads Miracleman #9 and “may be shocked into never wanting to have a baby, because now she sees a head lying out between the woman’s legs.” Almost every part of this is remarkable, but what stands out the most is simply the bewilderingly cack-handed attempt at understanding a woman’s perspective on childbirth. It is as though Geppi, horrified by the sight of a human being emerging from a vagina, has concluded that the only way the species has managed to survive all these millennia is through an elaborate social consensus to keep women from realizing how inherently gross they are. Which is obviously tremendously mockable, but in many ways the really significant is the underlying contempt; the idea that childbirth is such a horrifying thing in the first place, and that a thirteen-year-old girl is likely to be so mentally fragile as to swear of childbirth forever if she knew the awful truth.

Geppi’s letter is a fascinating and largely pathological piece. Its most revealing section comes when says, “I can imagine a 13-year-old-girl” who reads Miracleman #9 and “may be shocked into never wanting to have a baby, because now she sees a head lying out between the woman’s legs.” Almost every part of this is remarkable, but what stands out the most is simply the bewilderingly cack-handed attempt at understanding a woman’s perspective on childbirth. It is as though Geppi, horrified by the sight of a human being emerging from a vagina, has concluded that the only way the species has managed to survive all these millennia is through an elaborate social consensus to keep women from realizing how inherently gross they are. Which is obviously tremendously mockable, but in many ways the really significant is the underlying contempt; the idea that childbirth is such a horrifying thing in the first place, and that a thirteen-year-old girl is likely to be so mentally fragile as to swear of childbirth forever if she knew the awful truth.

That sense of moral panic was only amplified when a prominent retailer, Buddy Saunders, who owned five comic shops in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, wrote an open letter to the industry about his efforts to establish a ratings system within his stores and calling on publishers to be more responsible, specifically saying that superhero comics should “set an example that would make a boy scout proud” and decrying comics “with a hopeless, negative view of people, the world, and the future,” calling for comics with themes such as “pride, honor, and courage” as well as “beliefs in self and country” and expressing the “hope that comic writers might one day discover that not all authority is evil, dishonest, and not to be trusted.” Saunders, with five shops in a major metropolitan area, was a significant figure, and Geppi controlled the largest comics distributor in the country, so their calls naturally carried some weight. Indeed, Geppi, talking to The Comics Journal after his letter, explicitly cited support from Paul Levitz in his efforts to clean up the industry.

That sense of moral panic was only amplified when a prominent retailer, Buddy Saunders, who owned five comic shops in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, wrote an open letter to the industry about his efforts to establish a ratings system within his stores and calling on publishers to be more responsible, specifically saying that superhero comics should “set an example that would make a boy scout proud” and decrying comics “with a hopeless, negative view of people, the world, and the future,” calling for comics with themes such as “pride, honor, and courage” as well as “beliefs in self and country” and expressing the “hope that comic writers might one day discover that not all authority is evil, dishonest, and not to be trusted.” Saunders, with five shops in a major metropolitan area, was a significant figure, and Geppi controlled the largest comics distributor in the country, so their calls naturally carried some weight. Indeed, Geppi, talking to The Comics Journal after his letter, explicitly cited support from Paul Levitz in his efforts to clean up the industry.

A few weeks after Saunders and Geppi’s letters, at a convention in Ohio, Frank Miller got word of exactly how DC intended to support these efforts, namely an internal ratings system that would divide books into Universal, Mature, and Adult categories, with the Universal category (which would cover all books save for Swamp Thing, Vigilante, The Shadow, and Watchmen) under rules like “destructive behavior cannot be shown as acceptable behavior. It always will be discussed with accuracy, and casual or subtly negative behavior will not be dismissed as trivial” and the adult category explicitly not intended for use and serving more as an absolute line on what DC would never do. Miller was incensed, partially because the guidelines were crafted without any consultation with creators, and partially because, as he put it in a later interview, “people who are professional censors… let’s just say the job does not attract the best people.” Miller sprung into action, contacting a number of other creators, including Moore, who, to put it mildly, did not take the news well.

A few weeks after Saunders and Geppi’s letters, at a convention in Ohio, Frank Miller got word of exactly how DC intended to support these efforts, namely an internal ratings system that would divide books into Universal, Mature, and Adult categories, with the Universal category (which would cover all books save for Swamp Thing, Vigilante, The Shadow, and Watchmen) under rules like “destructive behavior cannot be shown as acceptable behavior. It always will be discussed with accuracy, and casual or subtly negative behavior will not be dismissed as trivial” and the adult category explicitly not intended for use and serving more as an absolute line on what DC would never do. Miller was incensed, partially because the guidelines were crafted without any consultation with creators, and partially because, as he put it in a later interview, “people who are professional censors… let’s just say the job does not attract the best people.” Miller sprung into action, contacting a number of other creators, including Moore, who, to put it mildly, did not take the news well.

Moore’s response, characterized by Rich Veitch (who was apparently one of Moore’s first calls) as having “hit the ceiling… HARD!” cannot be separated from his already growing discomfort with DC. But it’s no wonder he took this particularly personally. After all, one of his proudest moments at DC had been when Karen Berger secured freedom from the Comics Code on Swamp Thing, a moment he retained nothing but warm feelings about even after nearly every other aspect of his time at DC had turned sour for him. To see DC back down from that support and institute a ratings system that was clearly rooted in the same deeply conservative ethos that led the Comics Code to forbid any disrespect for authority, and moreover to do so in the face of direct attacks on him would have felt like an absolutely vicious betrayal, especially coming as it did so close to his unpleasant meeting with Jeanette Kahn.

Moore’s response, characterized by Rich Veitch (who was apparently one of Moore’s first calls) as having “hit the ceiling… HARD!” cannot be separated from his already growing discomfort with DC. But it’s no wonder he took this particularly personally. After all, one of his proudest moments at DC had been when Karen Berger secured freedom from the Comics Code on Swamp Thing, a moment he retained nothing but warm feelings about even after nearly every other aspect of his time at DC had turned sour for him. To see DC back down from that support and institute a ratings system that was clearly rooted in the same deeply conservative ethos that led the Comics Code to forbid any disrespect for authority, and moreover to do so in the face of direct attacks on him would have felt like an absolutely vicious betrayal, especially coming as it did so close to his unpleasant meeting with Jeanette Kahn.

DC, for its part behaved with a crashing lack of subtlety and respect. As the story broke, they quickly retreated behind public statements, so that when The Comics Journal tried to follow up with Janette Kahn about her December 1986 letter announcing the new ratings guidelines, Kahn asked that an interview be scheduled with DC’s spokesperson, Peggy May, who refused to set one up, “claiming that DC had already said all that needed to be said in press releases.” Similarly, when May asserted that “guidelines have been in use as long as anybody can remember and have been periodically updated,” she declined to actually provide any of these previous guidelines to refute claims, including ones from Len Wein, that no such guidelines actually existed. This, needless to say, did not do much to refute the claims from numerous freelancers that the ratings system was imposed from above without adequate consultation or dialogue. Nor did heavy-handed reactions like sacking Marv Wolfman from his editorial duties when he signed a letter penned by Moore and Miller complaining that “these new guidelines were developed without our consultation” and that the signees “take this opportunity to express our extreme displeasure.”

DC, for its part behaved with a crashing lack of subtlety and respect. As the story broke, they quickly retreated behind public statements, so that when The Comics Journal tried to follow up with Janette Kahn about her December 1986 letter announcing the new ratings guidelines, Kahn asked that an interview be scheduled with DC’s spokesperson, Peggy May, who refused to set one up, “claiming that DC had already said all that needed to be said in press releases.” Similarly, when May asserted that “guidelines have been in use as long as anybody can remember and have been periodically updated,” she declined to actually provide any of these previous guidelines to refute claims, including ones from Len Wein, that no such guidelines actually existed. This, needless to say, did not do much to refute the claims from numerous freelancers that the ratings system was imposed from above without adequate consultation or dialogue. Nor did heavy-handed reactions like sacking Marv Wolfman from his editorial duties when he signed a letter penned by Moore and Miller complaining that “these new guidelines were developed without our consultation” and that the signees “take this opportunity to express our extreme displeasure.”

But much as DC circled the wagons, the game was pretty much up. The letter, published in the Comics Buyer’s Guide, was signed not just by Moore, Miller, and Wolfman, but by twenty-four creators including Howard Chaykin, Bill Sienkiewicz, George Perez, Chris Claremont, Len Wein, and even John Byrne, who signed despite not objecting to the ratings system, not thinking it was censorship, and thinking that American Flagg! and Elektra: Assassin were pornography. DC might retaliate against an individual creator, and indeed did, but a list like that had to be mollified, especially with Miller, Moore, Wolfman, and Chaykin all proclaiming that they’d no longer work for DC unless they reversed their position. And though they waited until July of 1987 and denied even then that the ratings had anything to do with Geppi or Saunders’s letters, sure enough, they backed down, saying, with impressive understatement, that they “got a little more feedback than we anticipated” about the system.

But much as DC circled the wagons, the game was pretty much up. The letter, published in the Comics Buyer’s Guide, was signed not just by Moore, Miller, and Wolfman, but by twenty-four creators including Howard Chaykin, Bill Sienkiewicz, George Perez, Chris Claremont, Len Wein, and even John Byrne, who signed despite not objecting to the ratings system, not thinking it was censorship, and thinking that American Flagg! and Elektra: Assassin were pornography. DC might retaliate against an individual creator, and indeed did, but a list like that had to be mollified, especially with Miller, Moore, Wolfman, and Chaykin all proclaiming that they’d no longer work for DC unless they reversed their position. And though they waited until July of 1987 and denied even then that the ratings had anything to do with Geppi or Saunders’s letters, sure enough, they backed down, saying, with impressive understatement, that they “got a little more feedback than we anticipated” about the system.

The six month delay was, of course, as much a strategic choice as using Peggy May to give The Comics Journal the runaround in terms of actually talking to anyone at DC. It ensured that when DC reversed their position it was not so much another round of an ongoing fight so much as a footnote to a battle that was long since over, and whose participants were mostly exhausted with it already. Chaykin, for instance, proclaimed once it was all over that he’d “got bored with the ratings system argument soon after it started as a result of my inability to take it personally,” while Miller and Wolfman cheerily expressed their eagerness to get back to work with DC now that everything was resolved. It had not, on the whole, been a struggle in which anyone covered themselves in glory; as Gary Groth put it in a Comics Journal editorial, it mainly amounted to “a lot of grown-ups stamping their feet and holding their breaths. It was a frightful spectacle of supercilious sniping and intellectual sterility when it wasn’t merely irrelevant,” and noting that for all that Miller and his allies had claimed victory, the only actual concession on DC’s part had been to drop the Universal label, which was always the least necessary, since it largely coincided with the Comics Code.

The six month delay was, of course, as much a strategic choice as using Peggy May to give The Comics Journal the runaround in terms of actually talking to anyone at DC. It ensured that when DC reversed their position it was not so much another round of an ongoing fight so much as a footnote to a battle that was long since over, and whose participants were mostly exhausted with it already. Chaykin, for instance, proclaimed once it was all over that he’d “got bored with the ratings system argument soon after it started as a result of my inability to take it personally,” while Miller and Wolfman cheerily expressed their eagerness to get back to work with DC now that everything was resolved. It had not, on the whole, been a struggle in which anyone covered themselves in glory; as Gary Groth put it in a Comics Journal editorial, it mainly amounted to “a lot of grown-ups stamping their feet and holding their breaths. It was a frightful spectacle of supercilious sniping and intellectual sterility when it wasn’t merely irrelevant,” and noting that for all that Miller and his allies had claimed victory, the only actual concession on DC’s part had been to drop the Universal label, which was always the least necessary, since it largely coincided with the Comics Code.

But there’s one name, of course, that’s conspicuously absent from the reactions: Moore’s. This is unsurprising; unlike Chaykin, Moore had no problem taking it personally, in no small part because it blatantly was personal. Geppi’s attack on the loose morals of American comics was specifically aimed at Moore, and blatantly accused him of corrupting the youth of America. And DC had given into the attacks without blinking an eye, then spent months dissembling about it in the face of his protests while, in his view, trying to threaten him into coming back to work for them. Indeed, in his largest single piece on the controversy, an editorial in the February 13th, 1987 edition of Comics Buyer’s Guide entitled “The Politics and Morality of Ratings and Self-Censorship,” Moore decried the “disappointingly personal abuse” he’d received, and set out his own position in strikingly intimate terms, talking about his own children and the intensity with which he feels the need to teach them how to survive “in a world that is constantly changing and increasingly precarious.” In his view, responsible parenting means that he lets them read what they want, and “in the instance of their coming across something which puzzles or disturbs them – much more likely to happen with a newspaper than a comic book, incidentally – then I will simply do my best to explain the source of their distress or bafflement as honestly and as accurately as possible.” As for Geppi’s idea of shielding them from the idea of violence and sex, he notes that “when my eldest child was five she returned from school requesting money for a collection. When I asked her what for, she replied that one of her schoolfriends’ elder brother had gone berserk and murdered his mother with a kitchen knife before turning on his younger sibling, who fortunately escaped with severe injuries.” Subsequently, he went even further, declaring bluntly that he considered the people pressuring DC to be “actually evil.”

But there’s one name, of course, that’s conspicuously absent from the reactions: Moore’s. This is unsurprising; unlike Chaykin, Moore had no problem taking it personally, in no small part because it blatantly was personal. Geppi’s attack on the loose morals of American comics was specifically aimed at Moore, and blatantly accused him of corrupting the youth of America. And DC had given into the attacks without blinking an eye, then spent months dissembling about it in the face of his protests while, in his view, trying to threaten him into coming back to work for them. Indeed, in his largest single piece on the controversy, an editorial in the February 13th, 1987 edition of Comics Buyer’s Guide entitled “The Politics and Morality of Ratings and Self-Censorship,” Moore decried the “disappointingly personal abuse” he’d received, and set out his own position in strikingly intimate terms, talking about his own children and the intensity with which he feels the need to teach them how to survive “in a world that is constantly changing and increasingly precarious.” In his view, responsible parenting means that he lets them read what they want, and “in the instance of their coming across something which puzzles or disturbs them – much more likely to happen with a newspaper than a comic book, incidentally – then I will simply do my best to explain the source of their distress or bafflement as honestly and as accurately as possible.” As for Geppi’s idea of shielding them from the idea of violence and sex, he notes that “when my eldest child was five she returned from school requesting money for a collection. When I asked her what for, she replied that one of her schoolfriends’ elder brother had gone berserk and murdered his mother with a kitchen knife before turning on his younger sibling, who fortunately escaped with severe injuries.” Subsequently, he went even further, declaring bluntly that he considered the people pressuring DC to be “actually evil.”

Given that these were the terms on which he viewed the debate, it’s hardly a surprise that he saw its resolution differently. This carried some risk, as Moore put it, of him “looking like a shrill, over-reactive prima donna,” and certainly that was what DC sought to quietly paint him as, calmly explaining that, as Dick Giordano put it, the ratings system was not “a moral issue at all. It was essentially a business issue,” and complaining that “there was no way I could respond to people who were becoming so emotional about what seemed to me a very simple marketing device.” It hardly needed saying who Giordano had in mind there. And inasmuch as DC was, by this point, actively trying to rid themselves of a writer who they’d decided was simply too much of a rabble rouser, this was essentially how they went about it. Sure, Alan Moore writes some good comics, but he’s too crazy to work with.

Given that these were the terms on which he viewed the debate, it’s hardly a surprise that he saw its resolution differently. This carried some risk, as Moore put it, of him “looking like a shrill, over-reactive prima donna,” and certainly that was what DC sought to quietly paint him as, calmly explaining that, as Dick Giordano put it, the ratings system was not “a moral issue at all. It was essentially a business issue,” and complaining that “there was no way I could respond to people who were becoming so emotional about what seemed to me a very simple marketing device.” It hardly needed saying who Giordano had in mind there. And inasmuch as DC was, by this point, actively trying to rid themselves of a writer who they’d decided was simply too much of a rabble rouser, this was essentially how they went about it. Sure, Alan Moore writes some good comics, but he’s too crazy to work with.

Or, better yet, he’s so crazy he stormed off in a temper tantrum over an issue everybody else was happy to let go. That was, after all, the result. Unlike Miller, Chaykin, and Wolfman, Moore’s declaration that he wouldn’t work for DC anymore was never an ultimatum to get them to drop the ratings system. (Indeed, it would have been hypocritical in the extreme had he done so while simultaneously objecting to Kahn’s attempt to link DC’s further exploitation of the Watchmen characters to Moore’s willingness to keep working for them.) It was him reaching the end of his rope and deciding that he simply wasn’t interested in producing more superhero comics for a company that was willing to throw him under the bus to appease right-wing censors, threaten him, and nickel and dime him over royalties. And put like that, the only way in which Moore’s rope can really be described as short is in comparison with the mass of writers with little vision or ambition beyond churning out what Moore, even before he split with DC, described as “mass-produced rubbish churned out without a moment’s thought on the part of anyone involved.” Moreover, these creators often with strong senses of company loyalty engendered by years of participation fandom before entering the industry. And, for that matter, in comparison with the many fans for whom working at DC was a lifelong dream, and who were quick to denounce Moore for spurning the opportunity.

Or, better yet, he’s so crazy he stormed off in a temper tantrum over an issue everybody else was happy to let go. That was, after all, the result. Unlike Miller, Chaykin, and Wolfman, Moore’s declaration that he wouldn’t work for DC anymore was never an ultimatum to get them to drop the ratings system. (Indeed, it would have been hypocritical in the extreme had he done so while simultaneously objecting to Kahn’s attempt to link DC’s further exploitation of the Watchmen characters to Moore’s willingness to keep working for them.) It was him reaching the end of his rope and deciding that he simply wasn’t interested in producing more superhero comics for a company that was willing to throw him under the bus to appease right-wing censors, threaten him, and nickel and dime him over royalties. And put like that, the only way in which Moore’s rope can really be described as short is in comparison with the mass of writers with little vision or ambition beyond churning out what Moore, even before he split with DC, described as “mass-produced rubbish churned out without a moment’s thought on the part of anyone involved.” Moreover, these creators often with strong senses of company loyalty engendered by years of participation fandom before entering the industry. And, for that matter, in comparison with the many fans for whom working at DC was a lifelong dream, and who were quick to denounce Moore for spurning the opportunity.

It was not as though making Moore look eccentric was a hard feat. Indeed, it’s a largely accurate characterization of him, a fact he’d hardly deny. Certainly he appeared as such to DC, who at least made some effort to reconcile with Moore (although, of course, they presumably thought Kahn’s comment about not doing any prequels if Moore continued working for them was conciliatory and not, as Moore took it, a threat). In Moore’s telling, they “offered better financial deals” going forward, but as Moore put it, “I found [that] a little distressing because I wasn’t asking for a pay raise, and I would have hoped that no one thought I was asking for a pay raise.” But the truth is, one imagines that DC thought exactly that, the idea of a creator taking an entirely principled stand that was largely not about the money largely existing outside their default frame of reference.

But the principled stand made it easy to paint Moore as a crank to fans as well. With everyone other than Moore returning to the fold, Moore’s position, to casual observers not inclined to read pages of nuanced clarification in The Comics Journal, looked like he was refusing to work with DC over issues that had already been resolved. And with Moore, at least initially, largely declining to trash talk DC in detail beyond the ratings controversy, instead favoring fairly anodyne statements like “there’s a certain amount of disillusionment with DC. It’s nothing that I want to make a great noise about,” it was easy to mistakenly assume that the ratings controversy nobody else much cared about was all he objected to. And the principled nature of his stand was further undermined when DC responded to early reports of the split by pointing out that he still had both Batman: The Killing Joke and V for Vendetta in progress with them, implying that reports of his departure were greatly exaggerated when, in reality, Moore had always been clear that he would complete his contracted work with DC, but would not be taking on any new work for them.

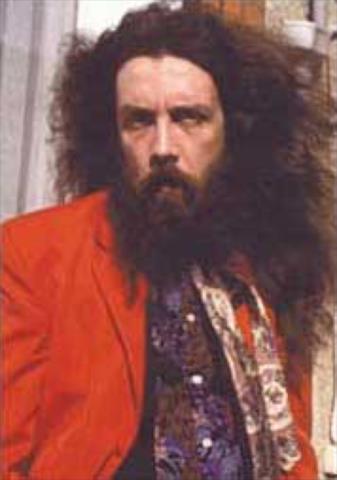

But the sense of Moore’s eccentricity went beyond that. Indeed, his eccentricity was at the heart of the ratings dispute, at least in terms of Moore’s conception of it. Moore’s view of Geppi’s attacks on him was not merely disagreement over the contention that his work was damaging to the moral fiber of America, but a contention that Geppi’s view was evil. He viewed Geppi as part and parcel of the Christian right in America, which he described as a “political blight upon the American landscape” that only had power because of their tactics of “making their political stance sound like the ultimate expression of good Christian morality.” Perhaps most tellingly, he compared the Moral Majority in America directly to the National Front in the UK, an actively neo-Nazi organization. This comparison is impossible to separate from Moore’s own personal life, which at the time involved what he described as an “experimental relationship” where he and his wife Phyllis lived with Debbie Delano (unrelated to Jamie Delano, although he adopted the surname from her as a pen name), a relationship that was an essential part of Moore’s passionate activism on gay rights in the period, and why, in early 1988, he mused about his desire to leave the country for less oppressive climes. This was not widely reported in the press, although open knowledge among Moore’s friends, and would not have been part of Geppi’s criticism, but it’s nevertheless key to realize that for Moore the moral criticism was not a theoretical issue, but a direct attack on the basic legitimacy of his own family.

But the sense of Moore’s eccentricity went beyond that. Indeed, his eccentricity was at the heart of the ratings dispute, at least in terms of Moore’s conception of it. Moore’s view of Geppi’s attacks on him was not merely disagreement over the contention that his work was damaging to the moral fiber of America, but a contention that Geppi’s view was evil. He viewed Geppi as part and parcel of the Christian right in America, which he described as a “political blight upon the American landscape” that only had power because of their tactics of “making their political stance sound like the ultimate expression of good Christian morality.” Perhaps most tellingly, he compared the Moral Majority in America directly to the National Front in the UK, an actively neo-Nazi organization. This comparison is impossible to separate from Moore’s own personal life, which at the time involved what he described as an “experimental relationship” where he and his wife Phyllis lived with Debbie Delano (unrelated to Jamie Delano, although he adopted the surname from her as a pen name), a relationship that was an essential part of Moore’s passionate activism on gay rights in the period, and why, in early 1988, he mused about his desire to leave the country for less oppressive climes. This was not widely reported in the press, although open knowledge among Moore’s friends, and would not have been part of Geppi’s criticism, but it’s nevertheless key to realize that for Moore the moral criticism was not a theoretical issue, but a direct attack on the basic legitimacy of his own family.

All of this speaks further to the degree to which Moore’s conflict with DC was a case of two entities talking past each other. It is not just that DC was largely uninterested in Moore’s ethical principles and personal life, or that they misunderstood his degree of investment in the financial aspects of things. It’s that DC saw the business of making comics as entirely that – a business, conducted dispassionately and with little attention other than the financials. This is what becomes rapidly apparent in statements like Len Wein’s description of Alan Moore as having been “part of the original process” of Watchmen, a statement that is in many regards staggering, mostly for the idea that there’s some larger portion of what Watchmen is that Moore is a relatively small fraction of, as opposed to what would seem, to almost any observer, the straightforward claim that Moore is overwhelmingly the figure most responsible for Watchmen being what it is, followed by Gibbons, with whoever thought of the $1.50 an issue format it was published in coming far enough behind that there is not even any particular mystery to their anonymity.

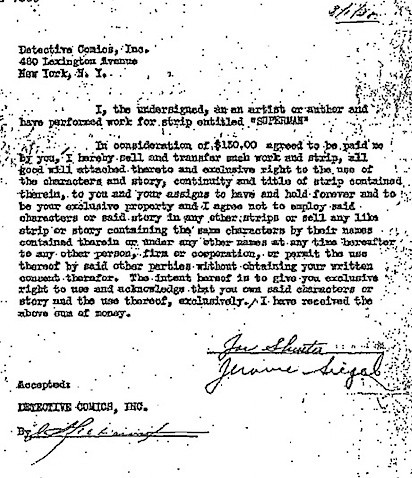

But while the position that Moore is merely the author of Watchmen while the company is the author of its success is deeply idiosyncratic, in its own way DC has been just as unwaveringly dedicated to the underlying principle as Moore is to his. Indeed, the principle is fundamentally embedded in the basic Watchmen contract, whereby Moore and Gibbons get a mere 8% royalty between them on the entire book, with DC keeping the other 92%. No, that’s not an unusual royalty structure in comics, or indeed in publishing in general, but nobody has ever suggested that DC’s values are out of the ordinary – just the degree of ruthlessness with which they pursue them. They are, after all, a company essentially founded on the notion that their purchase of the rights to Superman from Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster for $130 was entirely fair, as was Bill Finger dying without ever getting a credit on a Batman comic and Fawcett Comics being sued out of existence just so they could acquire Captain Marvel. Giving creators shitty deals is pretty much what they do.

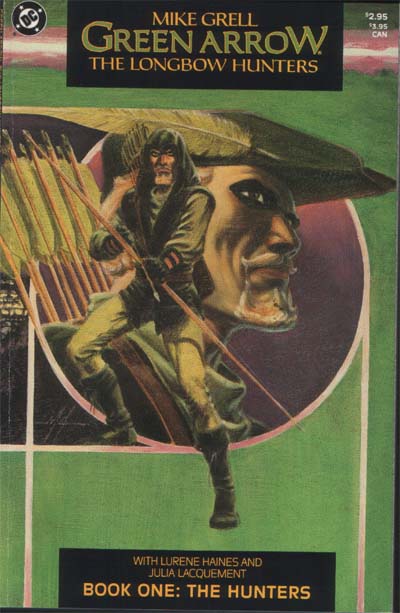

So from DC’s perspective, the loss of Moore was largely not a big deal. He had played his role in the process, identifying both the serious-minded take on superheroes and a fresh style of horror comics that proved to sell well. These, combined with ideas like the prestige format used for The Dark Knight Returns and the permanently-in-print trade paperback collection used for Watchmen, were more than enough for them to do what they wanted without any need to deal with the eccentrically principled. And for the most part they did. Moore’s run on Swamp Thing was followed smoothly by Rich Veitch taking over the writing while continuing on art, creating an easy transition and remaining in the same basic style. Jamie Delano, a close friend of Moore’s who had previously followed him on both Captain Britain and D.R. & Quinch, started up Hellblazer, featuring John Constantine, giving DC a second book in the Swamp Thing mould. Plus there were plenty of writers who came up through the same publications that Moore had who could be hired to do similar work. And DC continued with the grim realism introduced by Moore and Miller, putting out Mike Grell’s enormously successful prestige format Green Arrow: The Longbow Hunters, which reworked the title character to no longer use silly trick arrows, and with a plot that included the brutal torture of Black Canary followed by Green Arrow killing her torturer. And all of this was on top of things like John Byrne’s massively successful take on Superman, Marv Wolfman’s perennially popular Teen Titans comics, Dennis O’Neil’s acclaimed run on The Question, and former Dick Tracy scribe Max Allan Collins’s doing a brief stint on Batman. It was, in other words, still an extraordinarily good period for DC.

But there is a visible absence in all of this. The Veitch Swamp Thing and Delano Hellblazer runs were excellent books, and will come into focus within the War in good time, but their success in reprints has been a fraction of what Moore’s run has done. The Longbow Hunters sold well and remains in print, but is nothing compared to The Dark Knight Returns, and back issues go for roughly cover price, as opposed to the massive valuation of its predecessor. And as for Watchmen, well, there’s not even an obvious choice to compare it to. In the thirty years since its debut, DC has simply never come close to replicating its success. That they never matched the success of what is arguably the single most successful superhero graphic novel in the history of the genre is, of course, baked into the premise of Watchmen being the most successful, but to have the only other book to challenge it for the title, The Dark Knight Returns, be from the same year is, by any standard, a shocking failure at DC’s primary goal of replicating its own successful formula.

But there is a visible absence in all of this. The Veitch Swamp Thing and Delano Hellblazer runs were excellent books, and will come into focus within the War in good time, but their success in reprints has been a fraction of what Moore’s run has done. The Longbow Hunters sold well and remains in print, but is nothing compared to The Dark Knight Returns, and back issues go for roughly cover price, as opposed to the massive valuation of its predecessor. And as for Watchmen, well, there’s not even an obvious choice to compare it to. In the thirty years since its debut, DC has simply never come close to replicating its success. That they never matched the success of what is arguably the single most successful superhero graphic novel in the history of the genre is, of course, baked into the premise of Watchmen being the most successful, but to have the only other book to challenge it for the title, The Dark Knight Returns, be from the same year is, by any standard, a shocking failure at DC’s primary goal of replicating its own successful formula.

And while it can’t be blamed in any straightforwardly causal way on Moore’s departure, it is worth noting that DC’s position of strength was fleeting. The American comics industry expanded in the wake of Watchmen, fueled both by the burst of energy provided by more serious takes on superheroes and by a series of further innovations in formats and marketing, but this expansion would prove to be a disastrous bubble that nearly wiped the industry out, and from which the industry has not and may never entirely recover. The new dawn for the comics industry that so many articles about Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns excitedly predicted did not arrive.

The question of what went wrong is legitimately complex, and involved a number of factors that had nothing to do with DC, little yet with Moore. And yet it’s hard not to imagine that Moore’s proposals from a 1985 interview – dumping the glut of “mass-produced rubbish” suitable only for “a junkie” in favor of getting high quality writers, specifically suggesting looking outside the medium to writers like Ramsey Campbell – wouldn’t have produced a much healthier industry than trying to find like-for-like replacements for creators whose defining skill was their capacity for innovation. But that was exactly the sort of thing DC, with their heavy-handed and disingenuous attempt at a ratings policy and creator-hostile contracts, were determinedly ruling out.

And so for all that DC, in the wake of Moore’s departure, was in a position of apparent strength, it was undoubtedly a high risk move to alienate the most successful and vibrant new voice in American comics, especially given that the industry as a whole was in a decade-on-decade decline. The core of DC’s strategy – getting as much money as possible from the dedicated fans that the shift to the direct market helped identify – was strong in the short term, but depended on being able to continually generate new dedicated fans to replace ones who wandered away from comics. And there is little doubt that Moore, between his groundbreaking Swamp Thing run and the astonishing success of Watchmen, was one of the best tools they had for doing that. They spurned him, and faced an uncertain and dangerous future as a result.

And so for all that DC, in the wake of Moore’s departure, was in a position of apparent strength, it was undoubtedly a high risk move to alienate the most successful and vibrant new voice in American comics, especially given that the industry as a whole was in a decade-on-decade decline. The core of DC’s strategy – getting as much money as possible from the dedicated fans that the shift to the direct market helped identify – was strong in the short term, but depended on being able to continually generate new dedicated fans to replace ones who wandered away from comics. And there is little doubt that Moore, between his groundbreaking Swamp Thing run and the astonishing success of Watchmen, was one of the best tools they had for doing that. They spurned him, and faced an uncertain and dangerous future as a result.

And as for Moore, he was free. An essentially peerless genius in his field, in a position of more or less complete financial stability on the back of the Watchmen royalties, and beholden to no one, Alan Moore was in a position to do whatever he wanted. All he had to do was decide what that was.

And as for Moore, he was free. An essentially peerless genius in his field, in a position of more or less complete financial stability on the back of the Watchmen royalties, and beholden to no one, Alan Moore was in a position to do whatever he wanted. All he had to do was decide what that was.

“1. Crimes shall never be presented in such a way as to create sympathy for the criminal, to promote distrust of the forces of law and justice, or to inspire others with a desire to imitate criminals.

2. No comics shall explicitly present the unique details and methods of a crime.

3. Policemen, judges, government officials, and respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority.

4. If crime is depicted it shall be as a sordid and unpleasant activity.

5. Criminals shall not be presented so as to be rendered glamorous or to occupy a position which creates the desire for emulation.

6. In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.

7. Scenes of excessive violence shall be prohibited. Scenes of brutal torture, excessive and unnecessary knife and gun play, physical agony, gory and gruesome crime shall be eliminated.” – The Comics Code

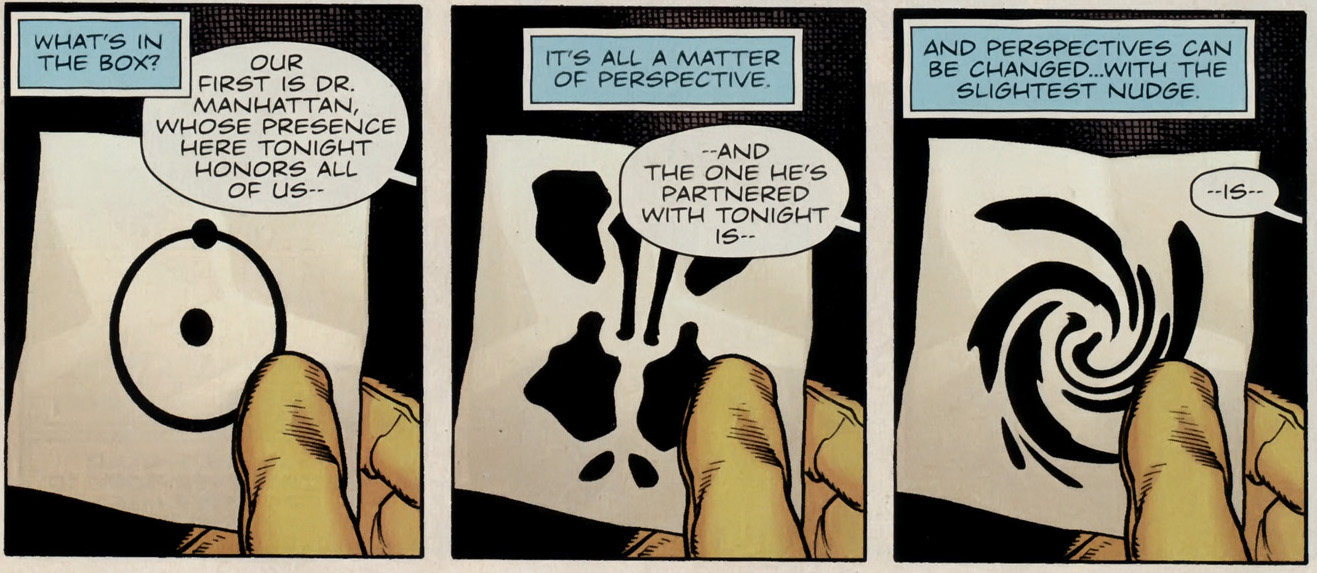

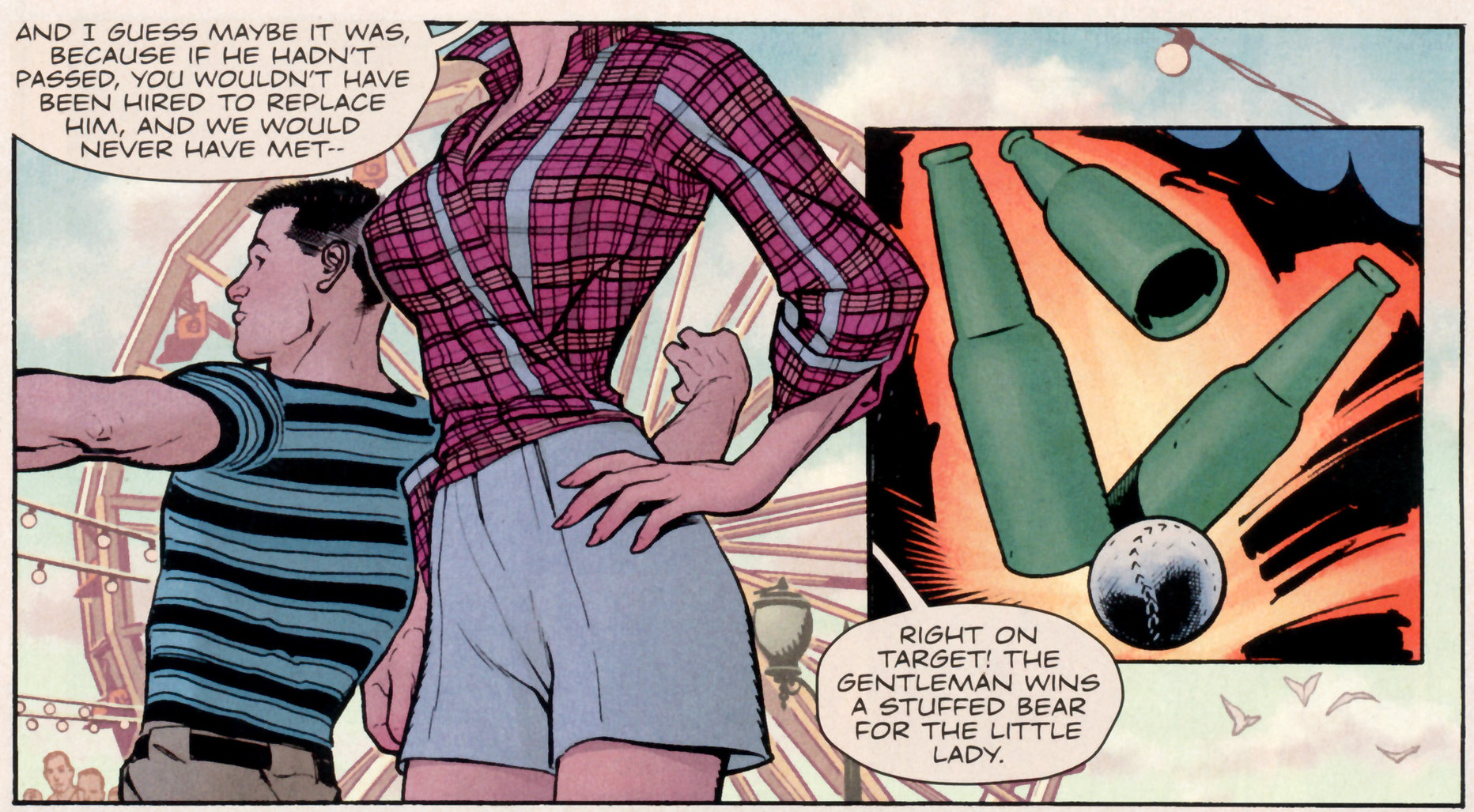

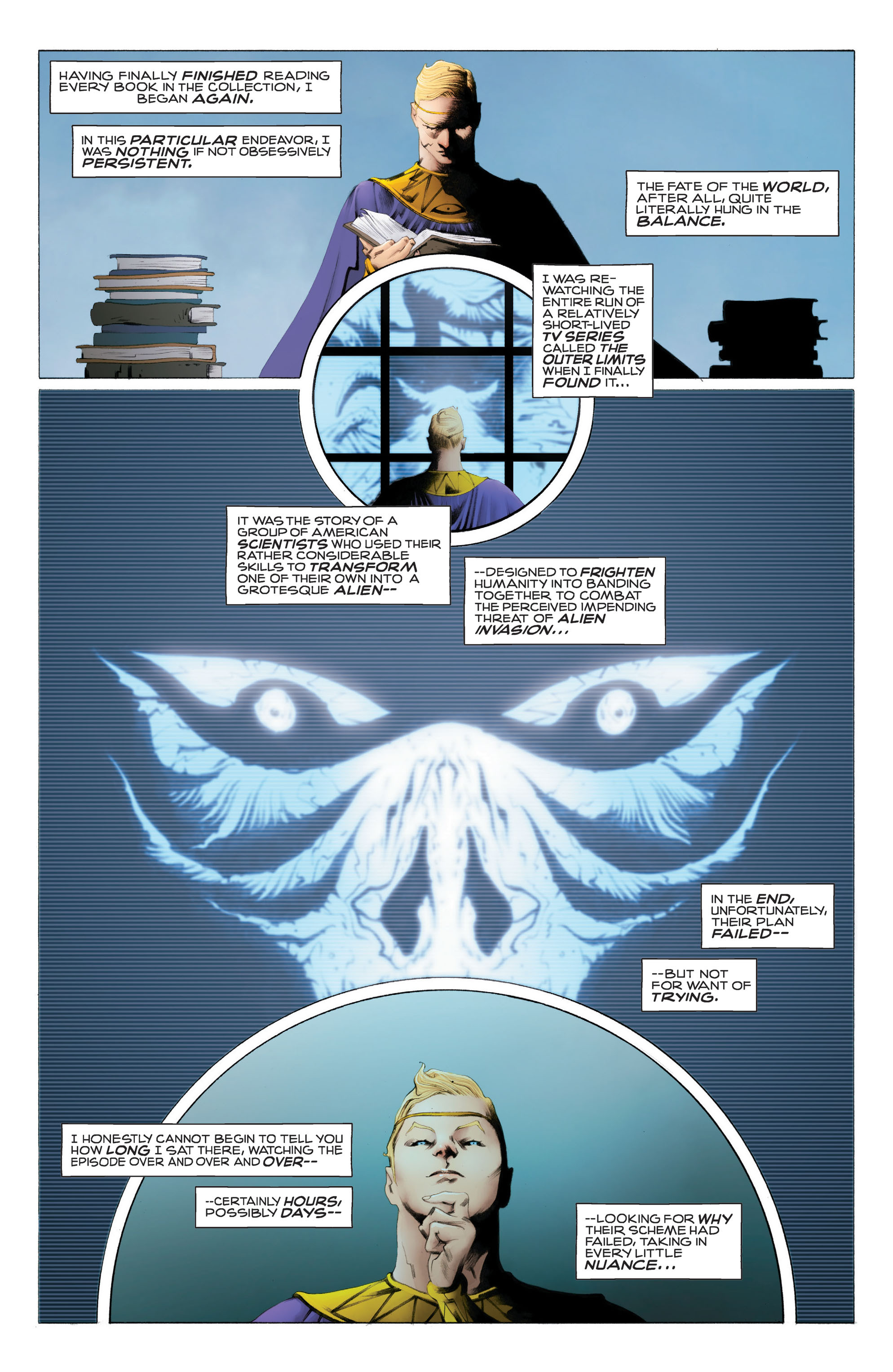

{The worst of the three main Before Watchmen writers, meanwhile, was by some margin J. Michael Straczynski, who tackled Before Watchmen: Night Owl and Before Watchmen: Dr. Manhattan, as well as the late addition two-issue Before Watchmen: Moloch title. Like Azzarello, Straczynski is not particularly concerned with fealty to the spirit of the source material. This is perhaps most evident in Before Watchmen: Dr. Manhattan, in which Straczynski makes drastic alterations to the overall lore of Watchmen by giving Dr. Manhattan an entirely new power explained in terms of Schrödinger’s Cat whereby he can manipulate the outcome of an unobserved event. This is not, it should be stressed, objectionable on its own. Were the Before Watchmen project ever to have actually worked, it would have had to be brave enough to do something significantly different from Watchmen; indeed, doing so was what elevated Before Watchmen: Silk Spectre over the others. And there is certainly nothing like a moral case to be made against it. While many of the attempts to compare Before Watchmen to Moore’s own work on characters other people created are exercises in completely missing the point, the observation that his standard approach to taking on a character is to make dramatic changes to them is a fair one. Moreover, it’s an approach that generally works.