Chapter Two: Places That Aren’t Even There Anymore (Absent Friends)

This is, perhaps, why so much ink has been spilled within the War on attempts to argue that this gap, in effect, does not exist – that Watchmen can be understood purely, or at least primarily, in terms of its influences, thus allowing those living in its wake to exist as though they are free from its vast and monolithic splendor. It is, after all, the easier option; it does not require staring too long at the cavernous depths within. It gives the comforting illusion that Watchmen is, at its heart, an easily solved mystery – a question with a definite answer. Nothing could be further from the truth, but for those who would otherwise find themselves caught in its blast, reduced to mere shadows cast by its incinerating radiance the idea that the book is simply some inevitable consequence of what came before is a useful delusion.

This is, perhaps, why so much ink has been spilled within the War on attempts to argue that this gap, in effect, does not exist – that Watchmen can be understood purely, or at least primarily, in terms of its influences, thus allowing those living in its wake to exist as though they are free from its vast and monolithic splendor. It is, after all, the easier option; it does not require staring too long at the cavernous depths within. It gives the comforting illusion that Watchmen is, at its heart, an easily solved mystery – a question with a definite answer. Nothing could be further from the truth, but for those who would otherwise find themselves caught in its blast, reduced to mere shadows cast by its incinerating radiance the idea that the book is simply some inevitable consequence of what came before is a useful delusion.

The relationship between Watchmen and these six characters is both well-documented and oft-misrepresented. In the eyes of his detractors, Moore’s contribution to Watchmen amounted to little more than changing the names of some obscure 60s superheroes, as in Dan Slott’s suggestion that “the real Before Watchmen comic would show Alan Moore reading stacks of Charlton comics.” Put bluntly, this is ridiculous. It is true that Moore’s first proposal to DC for what became Watchmen was titled Who Killed the Peacemaker, and made use of the Charlton characters. This was not, however, the earliest iteration of the story in the general case. As Moore puts it, he’d had “a vague story idea” along the lines of Watchmen in mind for years, based on the idea “that it would be quite interesting to take a group of innocent, happy-go-lucky superheroes like, say, the Archie Comics super-heroes, and suddenly drop them into a realistic and credible world,” noting that his “original idea had started off with the dead body of the Shield being pulled out of a river somewhere.” Then, while batting around ideas for a mooted DC project with Dave Gibbons, with whom he’d worked numerous times on 2000 AD, Moore found out that the Charlton characters had been recently acquired by DC and began developing the idea in detail with them, only to have DC ask him to rework it with original characters when it became obvious that Moore’s take was going to render the Charlton characters unsuitable for further use within DC.

That said, there are numerous plot points within Watchmen that clearly exist because the project was developed with the Charlton characters in mind. The fact that Doctor Manhattan’s powers are based in imagery of nuclear power, for instance, is clearly a legacy of Captain Atom, whose origin also involved being disintegrated and reincorporated. Similarly, the idea of there being two versions of Night Owl, the first a cop, the second a brilliant inventor, clearly originates in the publication history of the Blue Beetle, whose two incarnations have similar origins. Other small plot details such as the relationship between Doctor Manhattan and Silk Spectre also clearly originate in the details of the Charlton characters. In other words, even though Moore’s initial idea for Watchmen predated the idea of doing it with the Charlton characters, it’s undeniably the case that Watchmen, in its finished form, was influenced by the fact that it spent a period being developed as a revamp of six characters previously owned by Charlton Comics.

Equally, however, it’s clear that Moore was always interested in what Charlton didn’t do. His oft-reprinted pitch using the Charlton characters, for instance, focuses heavily on the psychology of the character, musing, “try to imagine what it would be like to be Captain America. The desk you’re sitting at and the chair you’re sitting on give less of an impression of reality and solidity to you if you know that you can walk through them as if they weren’t there at all. Everything around you is somehow more insubstantial and ghostly, including the people that you know and love.” This, it should be stressed, is not a theme that is substantively explored in Joe Gill’s original Captain Atom stories in Space Adventures, which are entirely unconcerned with the character’s interiority. More importantly, Moore highlights his unfamiliarity with the character when discussing this theme, noting that he “can’t remember if the Captain had a human love-interest back in those early days before Nightshade, but let’s say that he had, for the sake of argument. She is now forty-four, and she looks and feels forty-four as well. The young man that once she loved and possibly slept with is still as youthful and virile as ever, and it’s she who has aged and started past her prime. How would she feel about that? How would Captain Atom feel watching her grow old and eventually die while he remained the same constantly?” (Indeed, in a fact never remarked upon when Moore’s detractors bring up the Charlton characters, Moore openly admits in the Charlton pitch that “there are large amounts of the details concerning the Charlton characters that I’m simply unfamiliar with,” explaining that “there were hardly any comic shops over here in the Sixties, and I had to rely entirely upon the incredibly spotty newsstand distribution. On top of this, I had foolishly bound all of my beloved Charlton material into a book and then lent it to someone who I never saw again. As a result, most of the character details that I have built upon below are based upon my unreliable memory.”) Moore’s discussion of how Captain Atom would alter the geopolitical scene is similarly based in an active reaction against the actual Charlton material, in which Captain Atom is an uncomplicatedly jingoistic figure, generally suggesting that the best solution to the nuclear arm’s race would be if the United States won it, a situation that, in Joe Gill’s world, would be an unalloyed good.

More to the point, however, it’s clear that the decision to abandon the Charlton characters gave the project a significant creative jolt, especially with regards to the Comedian and Silk Spectre, who Moore evolves considerably from their original inspirations. When writing about Nightshade in the Charlton pitch, for example, Moore openly admits that “she’s the one I know the least about and have the least ideas on,” save for a vague desire to explore the idea of superhero sexuality in terms of her. It’s not until he creates Silk Spectre that the character begins to have any significant distinguishing characteristics, as she becomes “another second-generation super-hero similar to the new Nite-Owl,” a concept with no antecedent in Nightshade, and which forms the core of the actual Watchmen character. Similarly, Moore notes that the Comedian is “the most radically different of all our new characters to the original,” which is a considerable understatement. Joe Gill and Pat Boyette’s Peacemaker is an avowed pacifist defined by his use of non-lethal weaponry. The Comedian, on the other hand, is an openly nihilistic figure who clearly enjoys violence, a concept that is not so much based on the Peacemaker as it is the outright opposite.

More to the point, however, it’s clear that the decision to abandon the Charlton characters gave the project a significant creative jolt, especially with regards to the Comedian and Silk Spectre, who Moore evolves considerably from their original inspirations. When writing about Nightshade in the Charlton pitch, for example, Moore openly admits that “she’s the one I know the least about and have the least ideas on,” save for a vague desire to explore the idea of superhero sexuality in terms of her. It’s not until he creates Silk Spectre that the character begins to have any significant distinguishing characteristics, as she becomes “another second-generation super-hero similar to the new Nite-Owl,” a concept with no antecedent in Nightshade, and which forms the core of the actual Watchmen character. Similarly, Moore notes that the Comedian is “the most radically different of all our new characters to the original,” which is a considerable understatement. Joe Gill and Pat Boyette’s Peacemaker is an avowed pacifist defined by his use of non-lethal weaponry. The Comedian, on the other hand, is an openly nihilistic figure who clearly enjoys violence, a concept that is not so much based on the Peacemaker as it is the outright opposite.

But there is one area in which the relationship between the Charlton material and Watchmen is more complex and worth delving into, which is the evolution of Rorschach from Steve Ditko’s The Question. In the Charlton pitch, Moore talks about how the Question “is concerned with Truth and Morality, and if that means breaking corrupt laws that only exist because of the actions of dissident pressure groups and minorities, then he will break them without thinking about it.” This, at least, is well-grounded in the original comics, where the Question’s alter-ego was the crusading journalist Vic Sage, who repeatedly refuses to back down from investigating corruption no matter how much pressure is put on him and the station he works for. But in citing the strict line between good and evil, Moore is drawing as much from another Ditko-created character of the period, namely Mr. A, who Ditko created for Wally Wood’s underground book witzend, and who the Question was designed as a Comics Code-acceptable version of. Like the Question, Mr. A is a journalist/vigilante hero, but where the Question is generally written as a example of moral rightness, Mr. A stories are long on explicit lectures about the nature of good and evil. The first Mr. A comic, for instance, opens with Mr. A proclaiming, “fools will tell you that there can be no honest person! That there are no blacks or whites… that everyone is gray! But if there are no blacks or whites, there cannot even be a gray… since grayness is just a mixture of black and white! So when one knows what is black, evil, and what is white, good, there can be no justification for choosing any part of evil! Those who do so choose are not gray but black and evil… and they will be treated accordingly,” an opening that’s clearly what Moore is riffing on when, in “At Midnight All The Agents,” he has Rorschach declare that “there is good and there is evil, and evil must be punished. Even in the face of armageddon I shall not compromise in this.”

But there is more to this than might be immediately apparent. Mr. A, as a character, reflects Ditko’s larger investment in the work of Ayn Rand; his name, for instance, is a reference to her emphasis on Aristotle’s maxim “A is A.” Rand was a novelist and popular philosopher whose overt and insistent pro-capitalist position (forged when her wealthy Russian family lost their businesses during the October Revolution prior to her emigration to America) gave her considerable success among the political right; a New York Times article the same month that the first collected edition of Watchmen was released, for instance, talked about how the incoming Secretary of Commerce was an admirer of Rand’s work, as was newly installed chairman of the Federal Reserve Alan Greenspan, calling her the “novelist laureate” of the Reagan administration. (Rand, the article notes, was not a fan of Reagan, saying that “since he has no program and no ideology to offer, his likeliest motive for entering a Presidential race is power-lust.”)

Rand’s influence plays a significant part in Ditko’s work on both Mr. A and The Question – the second Mr. A strip, for instance, opens with a monologue about the absoluteness of good and evil before segueing into a lengthy discussion of how “only fools will tell you that money is the root of all evil” because “money is the tool of exchange” and how “for people who can exchange their abilities for an equal value – money and that money is exchanged for an equal value in products and services provided by other men’s abilities,” a viewpoint with clear roots in Rand’s vehement pro-capitalism. And the Question story in Blue Beetle #5 focuses on two paintings one described as representing “man’s inhumanity to man” by showing a man sitting in a gutter next to a used cigarette butt, and the other showing a strapping laborer standing near some jutting rocks. The plot tells of an art critic who hates the second picture for the way it “keeps accusing” him and reminding him of some unpleasant past experience, and of the criminal lengths to which the critic goes to try to destroy the painting (which Vic Sage has bought, in spite of the critic’s denunciation), a plot that has clear roots in Ayn Rand’s sense of aesthetics and the nature of man.

There are, of course, other works that have been identified as influences of Watchmen and used to try to diminish Moore’s contribution to the work. Len Wein, for instance, differed sharply with Moore over similarities between Veidt’s scheme at the end of Watchmen and an episode of The Outer Limits, an axe he has continued to grind for some years. But perhaps the one that has gotten the most traction is the suggestion that the comic is derivative of a 1977 novel by Robert Mayer called Superfolks. Much of the significance of this accusation comes from who made it, namely Grant Morrison, who included an item on it in a 1990 installment of what he describes as his “scurrilous, humour, gossip, and opinion column” Drivel in the British comics magazine Speakeasy. Indeed, Morrison does more than just suggest that Watchmen is derivative of Superfolks – he implicates Moore’s Miracleman run and his Superman story “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow” as well.

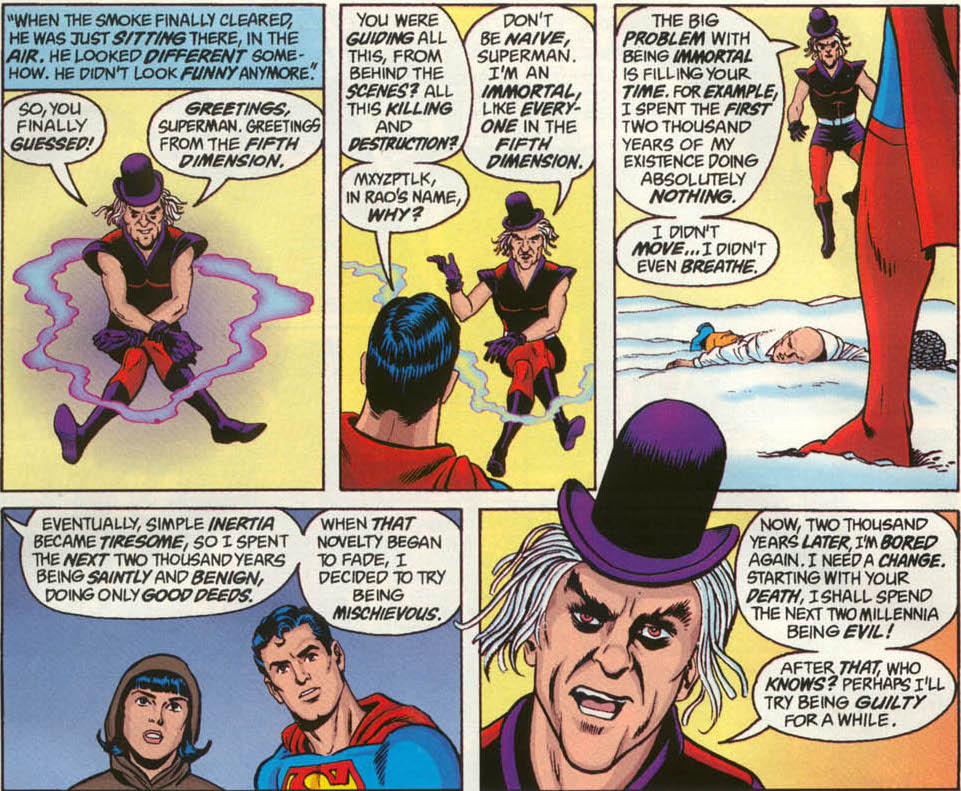

Unlike the accusation that Watchmen is derivative of the Charlton line, the accusation that Moore ripped off Mayer is based on actual plot details, as opposed to on characters that Moore was in practice clearly reacting against. As Morrison describes the plot, “It’s all about this middle-aged man who used to be a superhero like Superman. There’s a weird conspiracy involving various oddly-named corporate subsidies. There’s a simmering plot to murder the Superman guy and unleash unknown horrors on the world. There’s another middle-aged character in a rest home, who’s vowed never again to say the magic word that transforms him into Captain Mantra. There’s a corrupted and demonic Captain Mantra Junior and loads of other stuff about what it would be like if superheroes were actually real. In the end, the villain turns out to be a fifth-dimensional imp called Pxyzsyzgy, who has decided to be totally evil instead of mischievous.” For the most part, it is Miracleman and “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow” that are implicated by this – only the bit about corporate subsidies really points to Watchmen in particular. But Morrison made his view clearer in 2005 when he penned an introduction to a new edition of Mayer’s book and proclaimed that “Mayer had prefigured the era of so-called ‘deconstructionist’ superheroes” and called the book one “of the aboriginal roots nourishing the ‘80s ‘adult’ superhero comic boom,” both lines that blatantly implicate Moore’s superhero work from the 1980s in general.

This gestures towards a larger issue with treating Superfolks as a major antecedent to Watchmen, which is that very little of what Moore allegedly drew from it is actually all that innovative. Indeed, Pádraig Ó Méalóid, in a thorough analysis of Morrison’s claims, found that in almost every case either the similarities were overstated or an earlier antecedent could be found. (The sole exception was the use of Pxyzsyzgy, Mayer’s analogue for Mr. Mxyzptlk, as the ultimate villain behind everything, a plot point shared with the resolution of Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow.) But in many ways it’s more helpful to take a step backwards and look at what both Superfolks and Moore’s work are attempting, and situating it in a larger context. Ultimately, both of them are engaging with superheroes in a manner familiar from the New Wave of science fiction spearheaded, in the UK, by J.G. Ballard and Michael Moorcock, and in the US by a broader group of writers including Harlan Ellison, Samuel Delaney, and Ursula K. Le Guin.

The defining aspect of the New Wave was a turn away from pulp adventure and a focus on plausible extrapolation of science and towards using the tropes of science fiction and fantasy to explore human experience, applying the approaches of literary modernism and postmodernism to the genres. One major approach to this, pioneered by Michael Moorcock, was to rework pulp genres into new forms, asking, in various ways, what the subjective experiences of a character in a pulp adventure story might be like. In many regards, it was inevitable that this would eventually be applied to superheroes; that it took until 1977 for the first one to be released is mainly down to the fact that the companies producing the overwhelming majority of superhero stories, Marvel and DC, were fundamentally conservative in their publishing. But with a concept as historically inevitable as this, a priority dispute is almost beside the point.

Indeed, what’s most revealing about the priority dispute is the degree to which Moore’s influences largely leapfrog Mayer and go back to the larger New Wave tradition. The central idea of Superfolks comes from the New Wave, but its scattershot approach of random pop culture namedropping is just the Mad Magazine sight gag approach translated to text. (Indeed, Superfolks, with its focus on a barely disguised Superman and Captain Marvel, owes no small debt to Kurtzman and Wood’s “Superduperman,” which Moore has always cited as the primary inspiration for Miracleman.) Without the tremendous success of Watchmen and Grant Morrison’s mischief making, it is difficult to believe that the book wouldn’t have remained eternally out of print. The main result of comparing Watchmen and Superfolks is the realization that it is not the plot of Watchmen that makes it extraordinary, but the fact that Watchmen handles those plot elements much more intelligently, and much more in the spirit of the New Wave.

Indeed, what’s most revealing about the priority dispute is the degree to which Moore’s influences largely leapfrog Mayer and go back to the larger New Wave tradition. The central idea of Superfolks comes from the New Wave, but its scattershot approach of random pop culture namedropping is just the Mad Magazine sight gag approach translated to text. (Indeed, Superfolks, with its focus on a barely disguised Superman and Captain Marvel, owes no small debt to Kurtzman and Wood’s “Superduperman,” which Moore has always cited as the primary inspiration for Miracleman.) Without the tremendous success of Watchmen and Grant Morrison’s mischief making, it is difficult to believe that the book wouldn’t have remained eternally out of print. The main result of comparing Watchmen and Superfolks is the realization that it is not the plot of Watchmen that makes it extraordinary, but the fact that Watchmen handles those plot elements much more intelligently, and much more in the spirit of the New Wave.

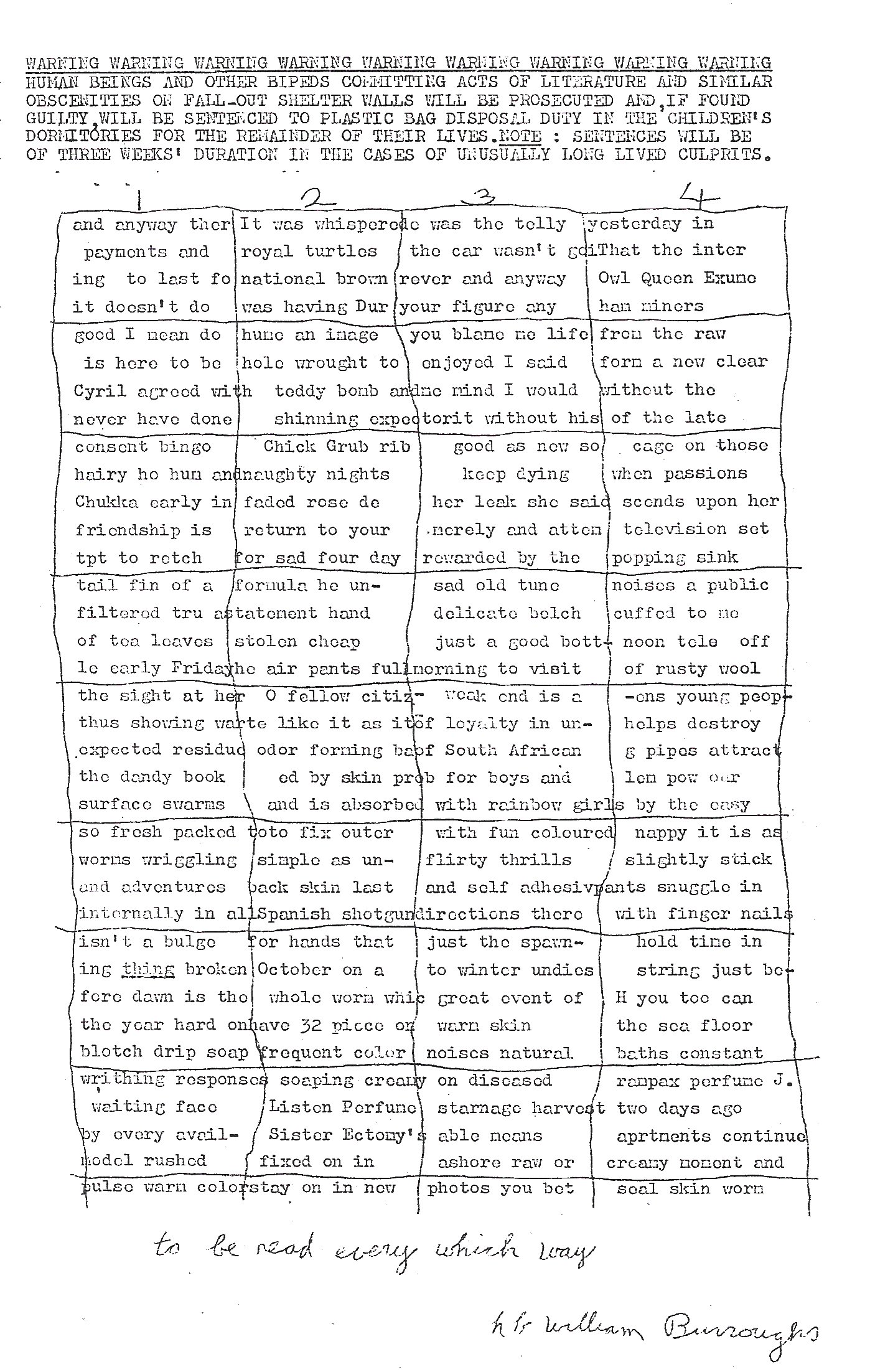

In this regard, it is worth noting one of the influences that Moore himself calls “one of my main influences” for Watchmen, and as the writer he’d pick “if I had to single out one major influence on my work,” namely William S. Burroughs – a writer who was also very much an intellectual touchstone for the New Wave. Unlike the works pejoratively cited as influences by Moore’s detractors, this is not an influence that occurs on the level of plot or characters. Watchmen does not hew to the plot of Naked Lunch, nor is there an obvious William Lee analogue running about within it. Instead the influence is largely conceptual. Its most obvious manifestation comes in the eleventh issue of Watchmen, which opens with a monologue from Ozymandias that begins “Multi-screen viewing is seemingly anticipated by Burroughs’ cut-up technique. He suggested re-arranging words and images to evade rational analysis, allowing subliminal hints of the future to leak through. An impending world of exotica, glimpsed only peripherally,” and ends by comparing this methodology to shamanistic traditions.

The cut-up technique, although associated with Burroughs, was not actually developed by him; he learned it in 1960 from the British artist Brion Gysin, who developed it independently, although others, including Burroughs, have identified earlier antecedents. The technique involves taking a physical page of text and cutting it into pieces, then rearranging the pieces to produce a new page in which fragments of the original are juxtaposed in new ways. As Burroughs put it in an interview, “any narrative passage or any passage, say, of poetic images is subject to any number of variations, all of which may be interesting and valid in their own right. A page of Rimbaud cut up and rearranged will give you quite new images. Rimbaud images – real Rimbaud images – but new ones.” The result leads to things like Gysin’s early cut-up poem “Minutes to Go,” which begins “the hallucinated have come to tell you that yr utilities / are being shut off dreams monitored thought directed / sex is shutting down everywhere you are being sent” and continues in much the same vein.

Burroughs, however, elaborated on the technique, coming up with variations like the fold-in technique, in which a page is folded in half and juxtaposed with a half of a different page, creating a strange hybrid of the two. But his most famous experiments with the technique came when he applied it to tape recordings instead of text. As Burroughs describes it in “The Invisible Generation,” in typical style, “the simplest variety of cut up on tape can be carried out with one machine like this record any text rewind to the beginning now run forward an arbitrary interval stop the machine and record a short text wind forward stop record where you have recorded over the original text the words are wiped out and replaced with new words do this several times creating arbitrary juxtapositions you will notice that the arbitrary cuts are appropriate in many cases and your cut up tape makes surprising sense”. But the appeal of this approach to Burroughs goes far beyond the mere fact that new and surprising meaning is created. As he puts it later in the same essay, “listen to your present time tapes and you will begin to see who you are and what you are doing here mix yesterday in with today and hear tomorrow your future rising out of old recordings”, which is what Ozymandias is referring to when he talks of “subliminal hints of the future” that leak through the cut-up technique. But Burroughs is in practice more radical than this – the passage continues, “you are a programmed tape recorder set to record and play back

who programs you

who decides what tapes play back in present time”.

This cuts to the heart of how Burroughs influenced Moore and Watchmen; Moore is explicit that Burroughs’s influence on him was “not the cut-up stuff, but his thinking about the way that the word and the image are used to control.” This is a view Burroughs spelled out in another essay in which he espouses the cut-up method, entitled “The Electronic Revolution,” which opens with a discussion of the nature of language and the word that comes to the astonishingly provocative claim that “the written word was literally a virus that made spoken word possible.” This is a significant statement, not least because it tacitly echoes Aleister Crowley’s declaration that magic is a “disease of language,” a phrase Moore would later use as the title for a collection of Eddie Campbell’s comic adaptations of his spoken word pieces. And Burroughs’s ultimate conclusions from this premise are wholly consistent with these implications. Burroughs’s claim is not just that language is a virus, but that language is a well-evolved virus that does not destroy its host, but instead attains a sort of equilibrium whereby it cannot even be detected or recognized as an infection. As a result, the borders of the concept get blurred – language becomes inexorable from the vast system of “control machines” that constrain us, a system that was, for Burroughs, inseparable from his own heroin addiction.

Nevertheless, Burroughs believed that by juxtaposing language from different contexts its tyrannical power could be turned against itself, allowing the artist to reshape the world. For instance, he suggests taking recordings of a politician’s speeches and “carefully editing in stammers mispronouncing inept phrases,” then taking a recording of the politician having sex, and then finally recording “hateful disapproving voices” before mixing them together and playing them, which he suggests would spell the end of the politician. But Burroughs goes much further than situations like this, in which there’s a presumptive audience for the eventual recording that might be affected by it. He also relates the story of his retaliation against a London cafe where he hated the service and the quality of the cheesecake, explaining how he recorded the sounds of the cafe and then visited the cafe again to play the recordings back, resulting in, as he tells it, the cafe going out of business. Later in the essay he suggests that the technique could be used to cause physical illnesses. Or, as Moore puts it, “Burroughs tends to see the word and the image as the basis for our inner, and thus outer realities. He suggests that the person who controls the word and the image controls reality.”

Nevertheless, Burroughs believed that by juxtaposing language from different contexts its tyrannical power could be turned against itself, allowing the artist to reshape the world. For instance, he suggests taking recordings of a politician’s speeches and “carefully editing in stammers mispronouncing inept phrases,” then taking a recording of the politician having sex, and then finally recording “hateful disapproving voices” before mixing them together and playing them, which he suggests would spell the end of the politician. But Burroughs goes much further than situations like this, in which there’s a presumptive audience for the eventual recording that might be affected by it. He also relates the story of his retaliation against a London cafe where he hated the service and the quality of the cheesecake, explaining how he recorded the sounds of the cafe and then visited the cafe again to play the recordings back, resulting in, as he tells it, the cafe going out of business. Later in the essay he suggests that the technique could be used to cause physical illnesses. Or, as Moore puts it, “Burroughs tends to see the word and the image as the basis for our inner, and thus outer realities. He suggests that the person who controls the word and the image controls reality.”

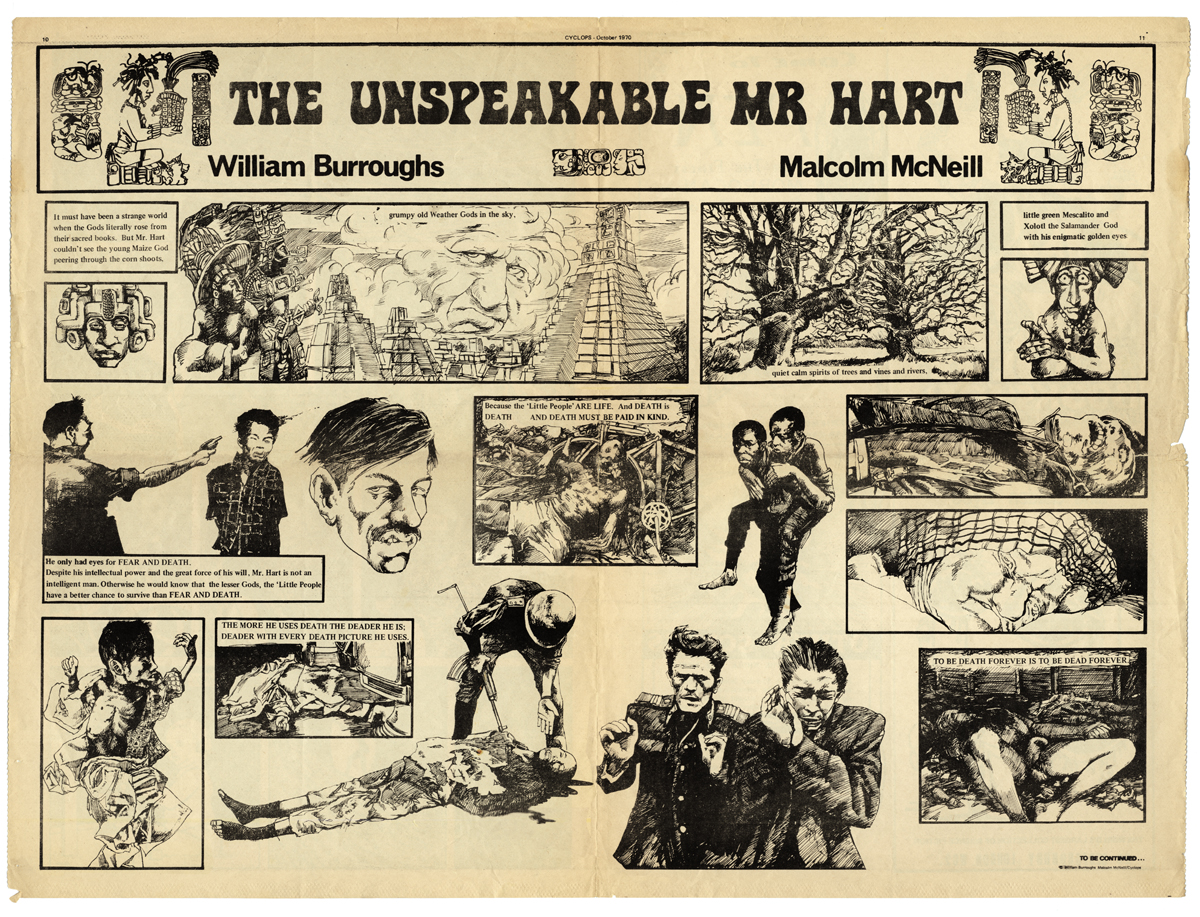

Moore’s interest in Burroughs, however, emerges from a peculiar implication of these viewpoints, specifically in how they apply to the medium of comics, which, as Moore points out, is a seemingly ideal medium for Burroughs given the way that juxtaposition is a basic part of its grammar. (Burroughs, for his part, never particularly focused on comics, aside from a short-run strip called The Unspeakable Mr. Hart, done with artist Malcolm MacNeill in a 1970 British underground magazine from the International Times crew, which the two continued as an illustrated book called Ah Pook Is Here. Interestingly, Burroughs and MacNeill never actually met while producing The Unspeakable Mr. Hart, and MacNeill found the project frustrating, as Burroughs’s scripts consisted of “half a page of copy… which didn’t read like comic book text at all.” They only met after the magazine broke down, when Burroughs proclaimed that “I want to meet the guy who knows how to draw me,” referring to MacNeill’s design for the eponymous Mr. Hart, which resembled Burroughs; in fact, MacNeill had never even seen a photograph of the man. This led to a lifelong friendship between the two collaborators. The Unspeakable Mr. Hart also served as a major influence in Dave Gibbons getting into comics. This sort of thing is par for the course with Burroughs.) As he explains, “with Watchmen I was trying to put some of his ideas into practice; the idea of repeated symbols that would become laden with meaning. You could almost play them like music. You’d have these things like musical themes that would occur throughout the work.” Although, of course, his repeated use of the overlaying of dialogue and images from different parts of the stories, itself a word/image version of Burroughs’s cut-up technique (and one anticipated by the proposed experiment that starts “The Invisible Generation,” where he proposes that the reader “turn off the sound track on your television set and substitute an arbitrary sound track prerecorded on your tape recorder street sounds music conversation recordings of other television programs you will find that the arbitrary sound track seems to be appropriate and is in fact determining your interpretation of the film track on screen people running for a bus in piccadilly with a sound track of machine-gun fire looks like 1917 petrograd”).

As theories of influence go, this has a major advantage over both the “Watchmen ripped off the Charlton characters” theory and the “Watchmen ripped off Superfolks” theory, namely that it actually offers some explanation of why and how Watchmen had the impact that it did. Any attempt to explain it in terms of a largely failed and forgotten line of 60s comics or a book that would have gone out of print forever if not for its tangental association with Watchmen is fundamentally inadequate: if the Charlton superhero comics and Superfolks were as important to Watchmen as some suggest, they’d also be, if not as important as Watchmen, at least comparable in stature. Burroughs, on the other hand, would suggest that it is not the ways in which the characters resemble other superheroes or the plot points that matter, except inasmuch as those characters and plot points serve as cut-up and spliced fragments to be manipulated, and that the engine that drives Watchmen’s success is, in practice, its structure and form, and the way in which those techniques are perfectly suited to magically reshaping the entirety of reality.

As theories of influence go, this has a major advantage over both the “Watchmen ripped off the Charlton characters” theory and the “Watchmen ripped off Superfolks” theory, namely that it actually offers some explanation of why and how Watchmen had the impact that it did. Any attempt to explain it in terms of a largely failed and forgotten line of 60s comics or a book that would have gone out of print forever if not for its tangental association with Watchmen is fundamentally inadequate: if the Charlton superhero comics and Superfolks were as important to Watchmen as some suggest, they’d also be, if not as important as Watchmen, at least comparable in stature. Burroughs, on the other hand, would suggest that it is not the ways in which the characters resemble other superheroes or the plot points that matter, except inasmuch as those characters and plot points serve as cut-up and spliced fragments to be manipulated, and that the engine that drives Watchmen’s success is, in practice, its structure and form, and the way in which those techniques are perfectly suited to magically reshaping the entirety of reality.

This also helps explain how Watchmen relates to what was, by the mid-80s, a significant body of revisionist takes on superheroes. The most obvious point of comparison here is Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, which came out from March to June of 1986, with the final issue coming a week after the first issue of Watchmen. The proximity of the two nuclear paranoia-fueled revisionist tales of aging superheroes, along with a wealth of news articles that cited them, along with Art Spiegelman’s Maus as heralding a new, mature era for comics (usually, as famously noted by Neil Gaiman, carrying titles along the lines of “Zap! Pow! Comics Aren’t Just for Kids Anymore!”), made them obvious bedfellows, an impression heightened by the fact that Moore and Miller were critical darlings among the same crowds.

This also helps explain how Watchmen relates to what was, by the mid-80s, a significant body of revisionist takes on superheroes. The most obvious point of comparison here is Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, which came out from March to June of 1986, with the final issue coming a week after the first issue of Watchmen. The proximity of the two nuclear paranoia-fueled revisionist tales of aging superheroes, along with a wealth of news articles that cited them, along with Art Spiegelman’s Maus as heralding a new, mature era for comics (usually, as famously noted by Neil Gaiman, carrying titles along the lines of “Zap! Pow! Comics Aren’t Just for Kids Anymore!”), made them obvious bedfellows, an impression heightened by the fact that Moore and Miller were critical darlings among the same crowds.

Moore was also a vocal proponent of Miller’s work, and had been since 1983, when he wrote an essay in The Daredevils praising and analyzing the Miller Daredevil run whose reprints headlined the magazine. (He also, of course, wrote “Grit,” a parody of Miller’s Daredevil work, for the same magazine.) Indeed, he wrote the introduction to the first trade paperback edition of The Dark Knight Returns, calling it “one of the few genuine comic book landmarks worthy of a lavish and more durable presentation.” And indeed, the work is a perennial bestseller and a landmark work, although its status as a classic has, in recent years, found itself endangered by a larger shift in Miller’s critical reception brought on in part by his unfortunate late career turn towards crass Islamophobia in works like Holy Terror and his tendency to do things like call the 2011 Occupy protests “a pack of louts, thieves, and rapists” due to their failure to sufficiently oppose radical Islam. And indeed, More has been a part of that turn, proclaiming in 2011 that “Frank Miller is someone whose work I’ve barely looked at for the past twenty years” before going on to criticize the majority of Miller’s work from that period, and suggesting, of his Occupy criticism, that “if it had been a bunch of young, sociopathic vigilantes with Batman make-up on their faces, he’d be much more in favour of it.”

Moore was also a vocal proponent of Miller’s work, and had been since 1983, when he wrote an essay in The Daredevils praising and analyzing the Miller Daredevil run whose reprints headlined the magazine. (He also, of course, wrote “Grit,” a parody of Miller’s Daredevil work, for the same magazine.) Indeed, he wrote the introduction to the first trade paperback edition of The Dark Knight Returns, calling it “one of the few genuine comic book landmarks worthy of a lavish and more durable presentation.” And indeed, the work is a perennial bestseller and a landmark work, although its status as a classic has, in recent years, found itself endangered by a larger shift in Miller’s critical reception brought on in part by his unfortunate late career turn towards crass Islamophobia in works like Holy Terror and his tendency to do things like call the 2011 Occupy protests “a pack of louts, thieves, and rapists” due to their failure to sufficiently oppose radical Islam. And indeed, More has been a part of that turn, proclaiming in 2011 that “Frank Miller is someone whose work I’ve barely looked at for the past twenty years” before going on to criticize the majority of Miller’s work from that period, and suggesting, of his Occupy criticism, that “if it had been a bunch of young, sociopathic vigilantes with Batman make-up on their faces, he’d be much more in favour of it.”

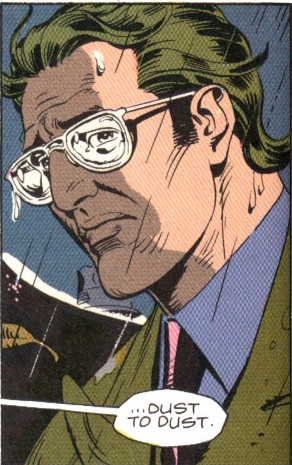

This last crack on Moore’s part highlights the specific way in which these later skirmishes of the War echo back upon The Dark Knight Returns, and it is in a way that both shows why Moore viewed it as such a landmark comic at the time and how it is a profoundly different work than Watchmen. Where Watchmen is intensely structured and defined by the impeccably clean line of Dave Gibbons, The Dark Knight Returns is a book that revels in its messiness, both structurally and in terms of Frank Miller’s bombastic scratch of a drawing style. Although he retained the high panel counts that characterized his breakout Daredevil work, basing the bulk of The Dark Knight Returns off of a 4×4 sixteen-panel grid, his figures in The Dark Knight Returns are strange and grotesque figures, misshapen and scratchy. Klaus Janson, in inking the comic, emphasizes this, working in a minimalist style further sold by Lynn Varley’s inkwashed colors. On top of this, the comic was published in what DC called their “prestige format,” a gluebound forty-eight page format published, like Watchmen, free of advertisements. Miller luxuriates in the space, and while there are no shortage of tight, intricately designed pages across the work, there are no shortage of cases where a scene spills oddly over into the first few panels of the next page, leaving often jarring hard cuts between unrelated scenes in the middle of a page. Plot elements are unveiled haphazardly – there’s a splash page in the second issue, for instance, emphasizing the death of a character who had never previously been mentioned in the story.

This sort of description can easily sound like criticism, but they are at the heart of the story’s power, which takes a similarly immoderate approach to the portrayal of Batman himself. Miller’s Batman is a militaristic tactician consumed by a pathological and almost mystical obsession. In one of the most chillingly effective sequences, as the aging Bruce Wayne finally decides to don the cowl and take to the roofs of Gotham again, Miller pens an inner monologue from the perspective of Batman talking to Bruce: “The time has come. You know it in your soul. For I am your soul. You cannot escape me. You are puny, you are small – you are nothing – a hollow shell, a rusty trap that cannot hold me – smoldering, I burn you – burning you, I flare, hot and bright and fierce and beautiful – you cannot stop me – not with wine or vows or the weight of age – you cannot stop me but still you try – still you run – you try to drown me out… but your voice is weak.” Once the Dark Knight makes his eponymous return, his voice is a staccato noir, confidently explaining everything in the world around him, even when he’s having the crap beaten out of him. (“He shows me what a fast kick is. Something explodes in my midsection. Sunlight behind my eyes as the pain rises. A moment of blackness. Too soon for that. Too soon. What’s wrong with me? Ribs intact. No internal bleeding.”) It is the idea of Batman pushed to a conceptual limit point: the most badass character imaginable, a point emphasized by the final villain he faces down, which is not the Joker (dispatched at the end of the third issue), but rather Superman.

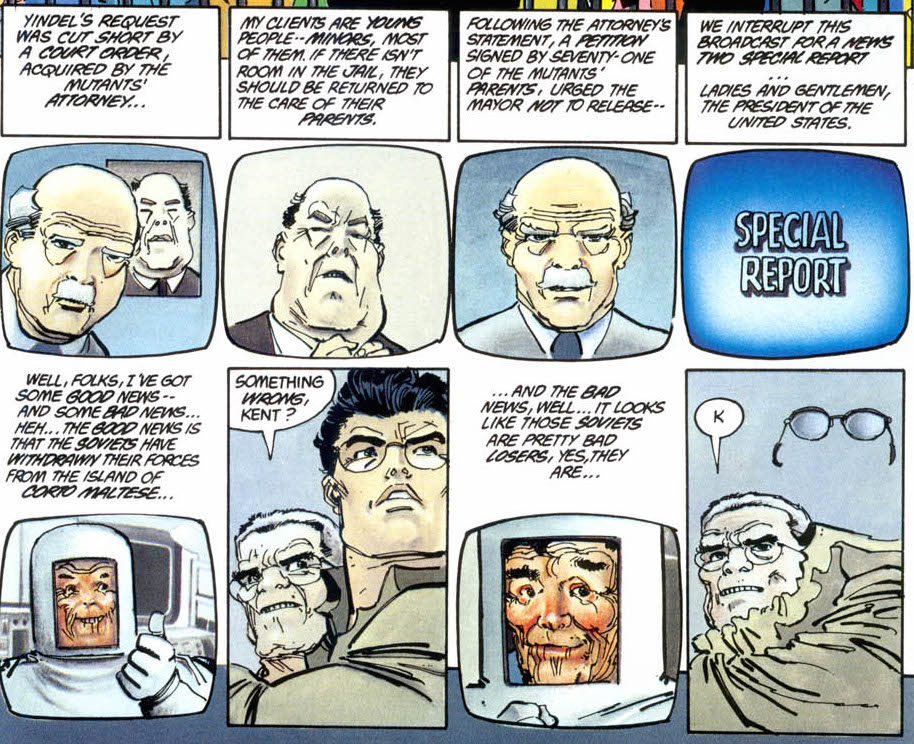

But all of this is filtered through the profound idiosyncrasy of Miller’s vision. His perfectly competent, fundamentally unstoppable Batman is the conceptual centerpiece of a world that bends around him – a pillar of perfected masculinity in a world otherwise defined by cowards, cronies, and crazies. Miller spends large portions of the book portraying talking heads on television discussing the plot, a sort of Greek chorus as filtered through the media-centric approach of Howard Chaykin’s American Flagg, and the world has the same sort of satirical excess of that book. As Moore describes it in his introduction, Batman “is seen as a near-fascist and a dangerous fanatic by the media while concerned psychiatrists plead for the release of a homicidal Joker upon strictly humanitarian grounds.” But it goes further than this – the mayor of Gotham City is a craven buffoon, the new police chief is a well-meaning classical liberal whose principled view of the law blinds her to the necessity of Batman, Superman is a naive stooge to the Reagan administration, with Reagan himself portrayed as a senile cowboy, and the youth of Gotham City is a bunch of cannibalistic mutants who, when Batman defeats their leader, become a sort of cargo cult Batman that endlessly appears on television to say, in the exact same words, that they will not be making any further statements in between beating petty criminals halfway to death.

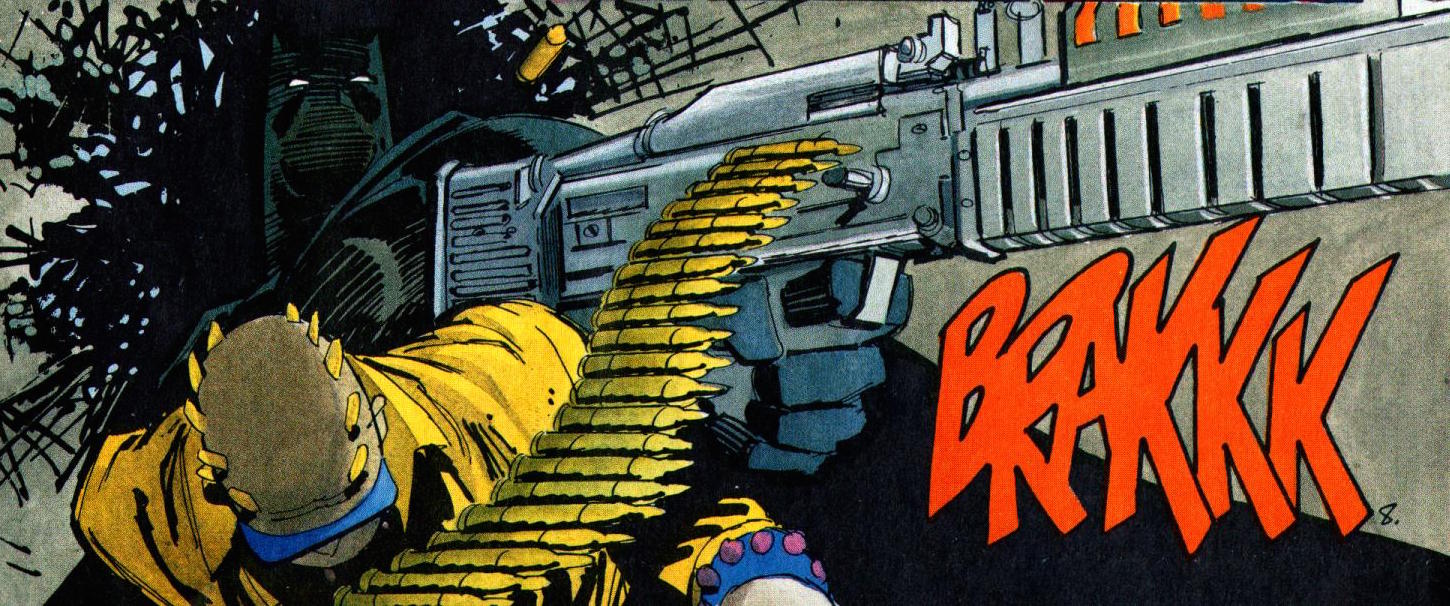

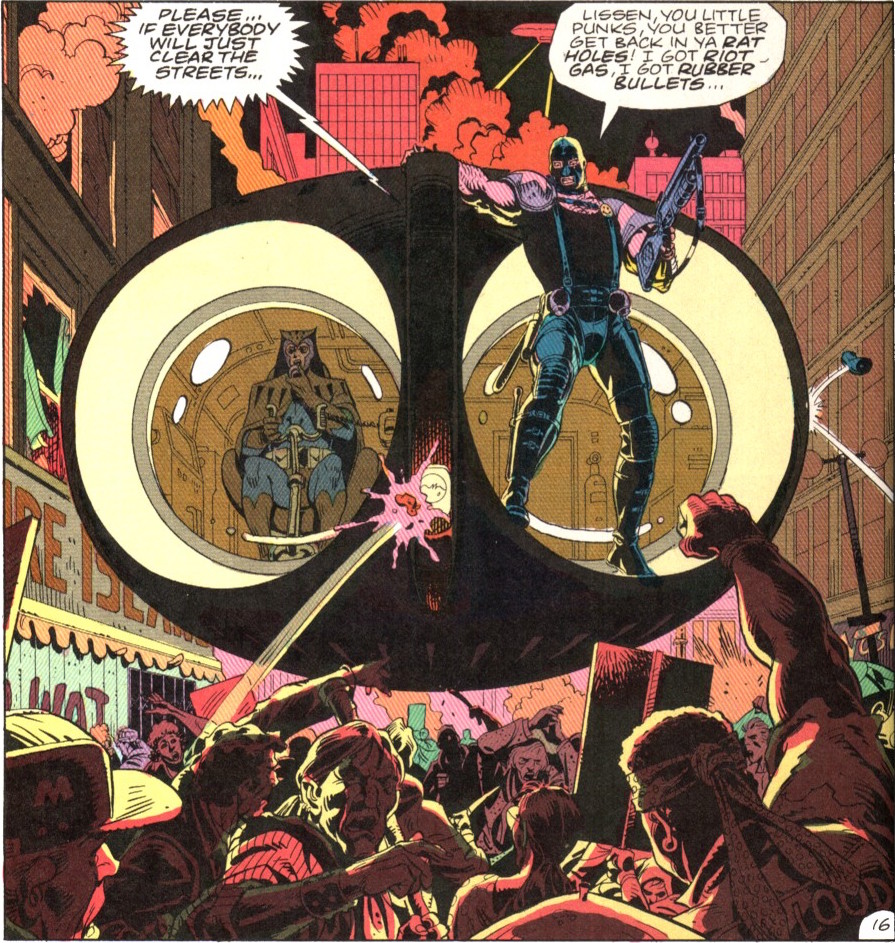

Were The Dark Knight Returns an influence on Watchmen in the traditional causal sense that fuels priority disputes, the obvious defense for Moore partisans would at this point be Judge Dredd, which shares its basic structure of an unbeatable hero serving as the final bastion of law and order in a fundamentally mad world, and its aesthetic of continual excess. And like Judge Dredd, the appeal of The Dark Knight Returns is that it is a fundamentally satirical work. And while nobody would mistake The Dark Knight Returns as going to the conceptual extreme of Judge Dredd, where, for all that the comic depends on the basic pleasure of watching the title character blow shit up, it’s ultimately unambiguous about the fact that he’s a bad guy. Ultimately, if nothing else, the idea that the company that wouldn’t even let Alan Moore kill the Peacemaker would allow one of their most popular characters to be undermined and subverted like that. All the same, The Dark Knight Returns clearly pushes in that direction when, for instance, Batman opens fire from the tank-like Batmobile, quipping via voiceover, “rubber bullets. Honest,” a moment that visibly nods at the fundamental absurdity of Batman’s sanitized violence. (Indeed, earlier in the issue Miller unambiguously has Batman grab one of the bad guys’ guns and shoot another in order to rescue a hostage, trading on the absurd contrast between Batman, in shadow, wielding a machine gun with a giant “BRAKKK” caption beneath him and, three panels later, cradling a child to his chest emblem.)

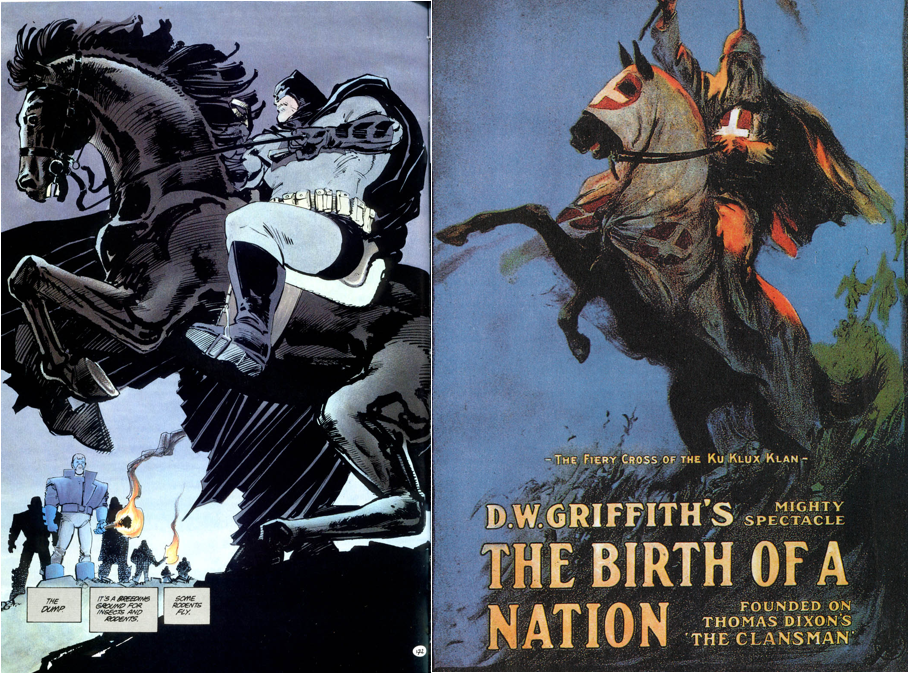

But the balance of frenzied energy and clever irony that fuels this is fragile thing, shattered by knowledge of future Frank Miller texts like Holy Terror, where his satirically excessive version of Batman (renamed “the Fixer,” but blatantly Batman both within the text and in terms of the story’s origin as a Batman project) becomes a crass vehicle for expressing Miller’s opinion that Muslims are a bunch of grunting barbarians and/or liberal arts majors. And once Miller falls off the delicate tightrope of visionary genius the hypocrisy of a Batman who simultaneously dramatically guns people down and moralizes about how guns are “the weapon of the enemy” becomes grating, and the splash page of Batman rearing up on a magnificent stallion before gathering his army of young sociopathic vigilantes in makeup starts to look like the D.W. Griffiths lift it is. In short, what looked like a bleak satire of America in the 1980s now looks uncomfortably like a sincerely presented vision of what America could be.

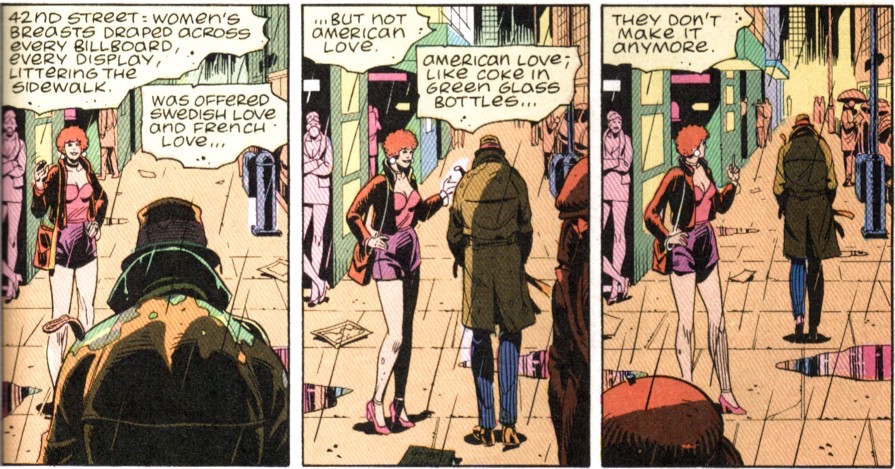

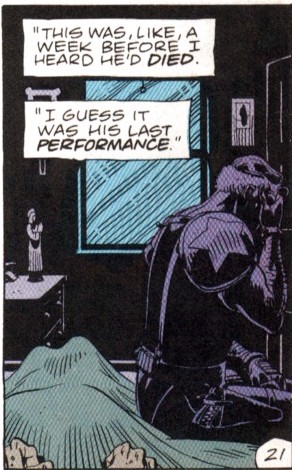

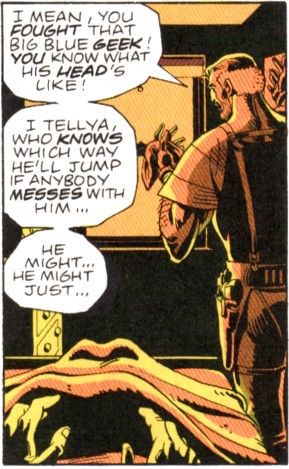

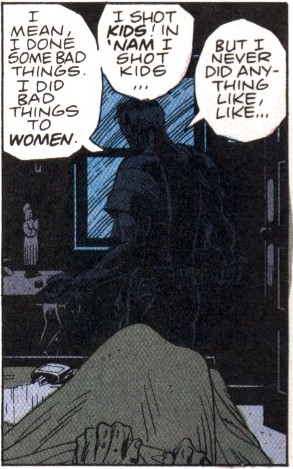

But in this regard the similarities between The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen are, perhaps, greater than might be apparent. After all, if The Dark Knight Returns was widely read as being less sincere than it now appears that it was, Watchmen was widely read as being considerably more sincere than it was, particularly in terms of Rorschach (and, though he’s rarely mentioned in these terms, the Comedian), whose excesses are in many regards similar to those of Miller’s Batman. And, it must be said, it is not as though a reading of The Dark Knight Returns whereby Batman is a quasi-fascist fantasy figure, or for that matter one of Watchmen in which Rorschach is viewed as an aspirational one was, in practice, unpopular. For all that Miller’s politics have taken a turn towards the unpleasant and his art has grown self-parodic in its grotesqueries, after all, he can still move an impressive number of units on the direct market. And likewise, for all that it is Watchmen’s pathological formalism that defines its uncanny power, the cold reality is that its success depended on the large number of fans who lovingly remember “dog carcass in alley this morning” while conveniently forgetting “American love; like coke in green glass bottles” when thinking about Rorschach as a character.

This is a central tension within the book, and one that’s crucial to understanding Moore’s eventual and profound alienation from it. Moore has repeatedly expressed his considerable discomfort with the number of people who, as he puts it, “come up to me saying, ‘I am Rorschach! That is my story!’,” describing his reaction as hoping that they will “just, like, keep away from me and never come anywhere near me again as long as I live.” And it’s difficult to disentangle this revulsion from his concurrent revulsion at fan culture, based on his negative experiences being mobbed at conventions, which left him temporarily suffering from night terrors. It would be ridiculous to suggest that Moore did not want Watchmen to succeed, but equally, it’s clear that the terms on which it did succeed were intensely upsetting to him. In a fundamental sense, the book he wrote and the book people read were two very different things. And the gulf between those two versions of Watchmen is a huge and fundamental part of the reaction to the book.

_001-001.jpg)

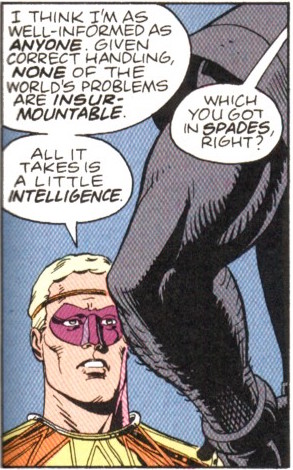

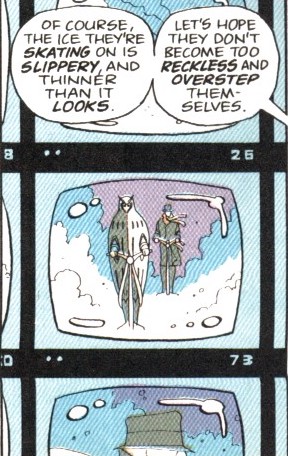

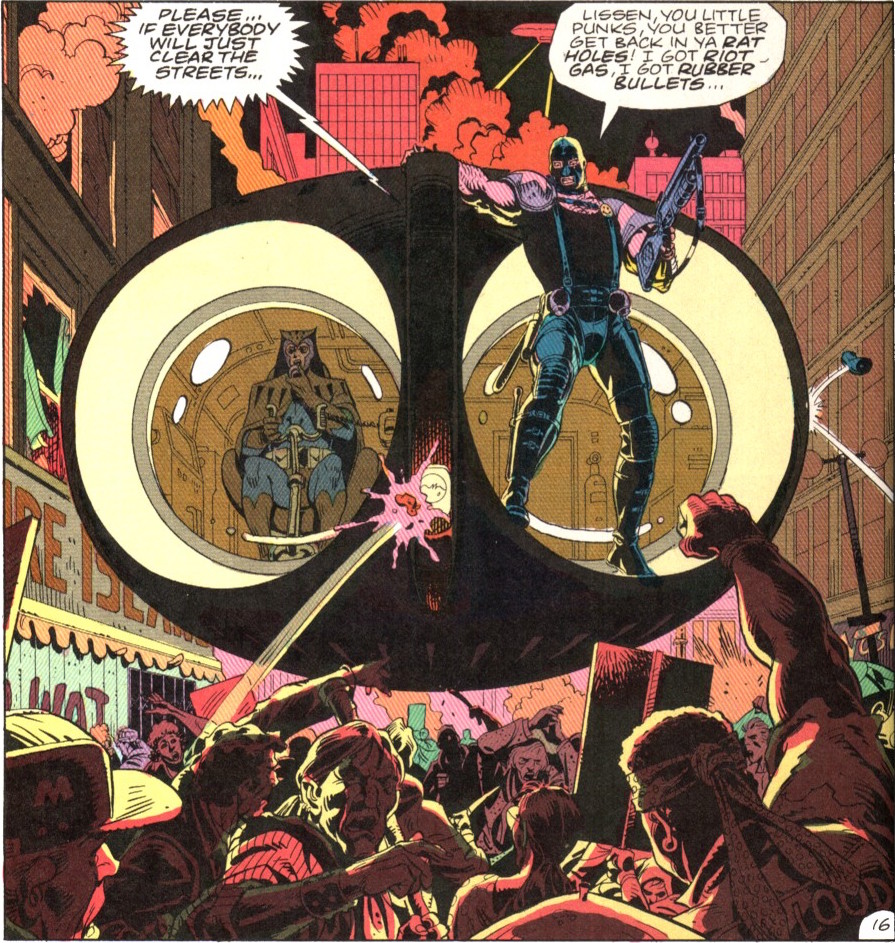

It is also a gulf explored by Grant Morrison in his 2014 comic Pax Americana, part of his larger Multiversity series of semi-connected one-shots exploring alternate Earths in the DC Multiverse he had helped restore in 2007. The comic was explicitly modeled after Watchmen – indeed, Morrison had been hyping it since 2009, describing it as rooted in “that sort of crystalline, self-reflecting storytelling method” and an attempt to capture what would happen “if Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons had pitched the Watchmen now, rooted in a contemporary political landscape, but with the actual Charlton characters instead of analogues.” In this regard, what is perhaps most significant about it is that it is not an imitation of Watchmen as such. Where many comics overtly following from Watchmen adopt its nine panel grid, Pax Americana is based around an eight panel grid, albeit significantly more loosely than Watchmen is around its grid. This is in turn reflected within the comic, which uses the figure eight as a recurring visual motif. But Morrison slyly plays on the image, using it not just to represent the number 8, but as an infinity symbol, a figure that tacitly invokes Doctor Manhattan’s line shortly before the end of Watchmen, “nothing ever ends.”

It is also a gulf explored by Grant Morrison in his 2014 comic Pax Americana, part of his larger Multiversity series of semi-connected one-shots exploring alternate Earths in the DC Multiverse he had helped restore in 2007. The comic was explicitly modeled after Watchmen – indeed, Morrison had been hyping it since 2009, describing it as rooted in “that sort of crystalline, self-reflecting storytelling method” and an attempt to capture what would happen “if Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons had pitched the Watchmen now, rooted in a contemporary political landscape, but with the actual Charlton characters instead of analogues.” In this regard, what is perhaps most significant about it is that it is not an imitation of Watchmen as such. Where many comics overtly following from Watchmen adopt its nine panel grid, Pax Americana is based around an eight panel grid, albeit significantly more loosely than Watchmen is around its grid. This is in turn reflected within the comic, which uses the figure eight as a recurring visual motif. But Morrison slyly plays on the image, using it not just to represent the number 8, but as an infinity symbol, a figure that tacitly invokes Doctor Manhattan’s line shortly before the end of Watchmen, “nothing ever ends.”

_001-002.jpg)

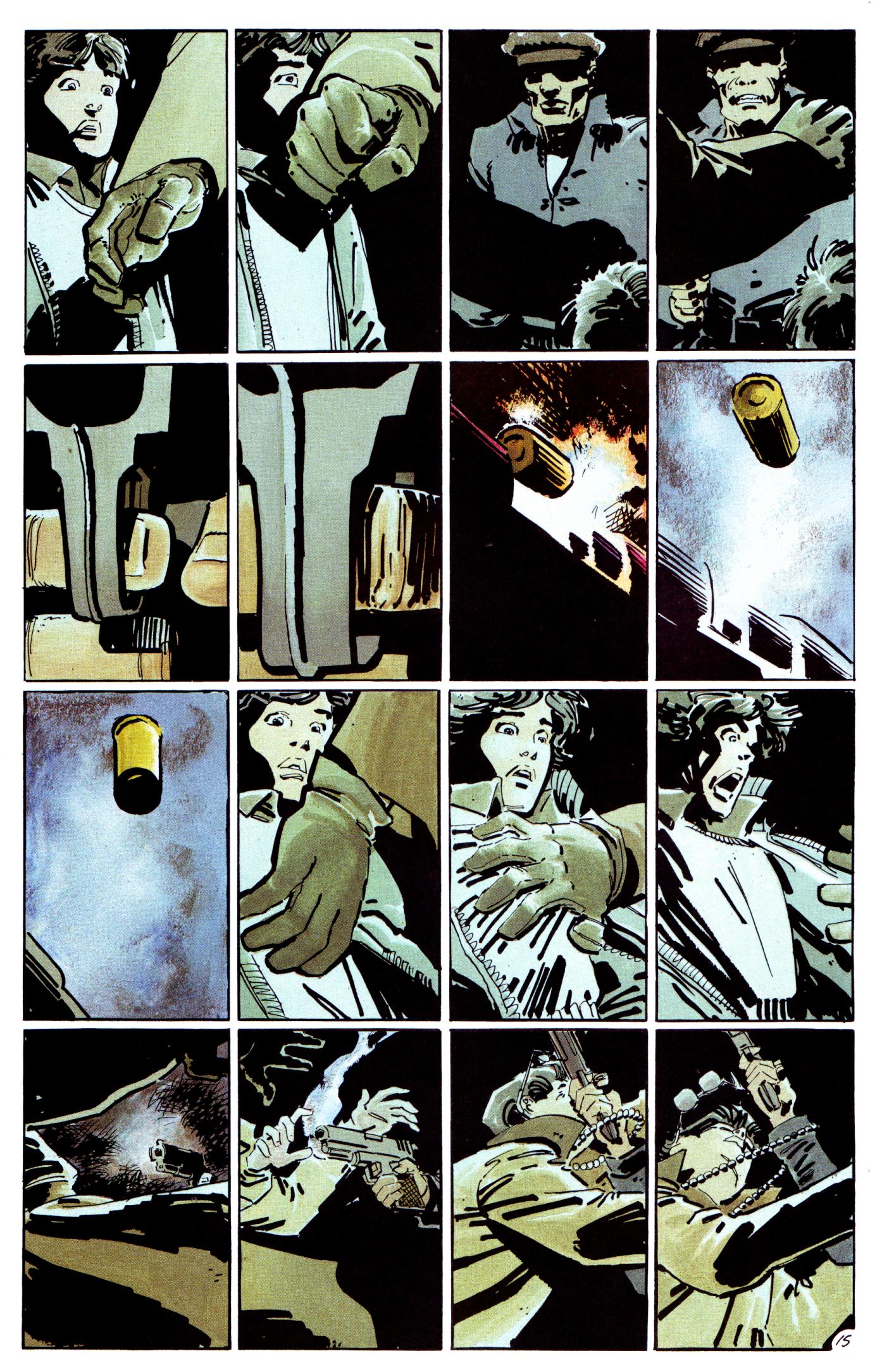

Indeed, the complex notion of time implied by this iconography manifests throughout Pax Americana. Like Watchmen, it engages in considerable non-linear storytelling, but where Watchmen has a clear forward-moving narrative that runs from the beginning of issue #1 to the end of issue #12, albeit one punctuated by a number of clearly designated flashbacks, Pax Americana is simply told non-chronologically, with the reader left to piece together the actual sequence of events within the narrative. Its opening section, depicting the assassination of the President of the United States by the Peacemaker (shot in an open-topped motorcade, a tacit reference to Watchmen’s suggestion, made explicit in the film, that the Comedian was involved in the Kennedy assassination) in reverse over the course of three pages, a clear sign that this is not a comic with a straightforward relationship to time.

_001-017.jpg)

Given this, and the fact that Watchmen, with its rejection of the idea of endings and its own looped structure, whereby the final panel echoes the first, is similarly ambivalent about the precise sequence in which causes and effects need occur, it is just as reasonable to treat Pax Americana as an influence on Watchmen as it is the other way around. After all, time is, as Morrison pointed out in commencing the War, just a four letter word. This is, admittedly, a strange approach, especially for Pax Americana, which is not a comic in which Morrison really lays out a worldview he supports. Rather, it is a critique of a particular vision of superheroes; one defined by the hermetically sealed (and indeed Hermetically sealed) closed loop of the figure eight. Throughout it, people espouse about hidden patterns and systems organizing the world, dialogue that is echoed in the intricate and detailed presentation. And yet for all its ornate formalism, it is a comic of broken designs and symmetries; a fact remarked upon by the murdered President Hartley when he tells Captain Atom that his goal is to “restore symmetry to a broken world.” But Captain Atom is, in this telling, mad, as, it seems, is President Hartley, whose utopian vision of superheroes turns out to be a pathology originating from his accidental murder of his superhero father.

_001-032.jpg)

It is, in other words, an inherently unfinished world; indeed, one that cannot be finished. It is unstable, right down to its default page layout, two rows of four panels each, which results in oddly tall, narrow panels that feel as though they might topple at any moment. This fits with the larger Multiversity project, a self-consciously over the top exploration of the infinitely variable possibilities of superheroes. This is what Morrison speaks of in Supergods, written around the same time as Pax Americana was being conceived, when he talks about superheroes as stories that speak “loudly and boldly to our greatest fears, deepest longings, and highest aspirations. They’re not afraid to be hopeful, not embarrassed to be optimistic, and utterly fearless in the dark. They’re about as far from social realism as you can get, but the be best superhero stories deal directly with mythic elements of human experience that we can all relate to, in ways that are imaginative, profound, funny, and provocative. They exist to solve problems of all kinds and can always be counted on to find a way to save the day. At their best, they help us to confront and resolve even the deepest existential crises. We should listen to what they have to tell us.”

And so Moore did. He remoulded the world of Earth-4, removing the old Charlton characters and replacing them with analogues, as well as one addition of his own. Instead of President Hartley, the traumatized son of a superhero who sought ultimately to remove them from the world, he created exactly what Morrison called for: a superhero who would solve all problems and save the world, resolving even the most apocalyptic of existential crises. He inverted the infinite possibility, so that instead of symmetry endlessly fracturing outwards it is an ornately interior structure, the chaos ensconced as a fractal cut-up of recurring iconography. He replaced the teetering eight-panel grid with a tidier nine panels, stacked three high in a comfortingly monolithic stability, each one a miniature of the whole. And instead of Frank Quitely’s vividly grotesque figures he had Dave Gibbons’s tight, orderly linework, the better to impose a sense of absolute and all-encompassing stillness throughout the work. In other words, he took Morrison’s utopian vision of superheroes to its logical endpoint, extracting from the infinitude of possibilities within the concept a singular solution to be analyzed and interrogated; to be asked what a world saved by superheroes would look like.

And so Moore did. He remoulded the world of Earth-4, removing the old Charlton characters and replacing them with analogues, as well as one addition of his own. Instead of President Hartley, the traumatized son of a superhero who sought ultimately to remove them from the world, he created exactly what Morrison called for: a superhero who would solve all problems and save the world, resolving even the most apocalyptic of existential crises. He inverted the infinite possibility, so that instead of symmetry endlessly fracturing outwards it is an ornately interior structure, the chaos ensconced as a fractal cut-up of recurring iconography. He replaced the teetering eight-panel grid with a tidier nine panels, stacked three high in a comfortingly monolithic stability, each one a miniature of the whole. And instead of Frank Quitely’s vividly grotesque figures he had Dave Gibbons’s tight, orderly linework, the better to impose a sense of absolute and all-encompassing stillness throughout the work. In other words, he took Morrison’s utopian vision of superheroes to its logical endpoint, extracting from the infinitude of possibilities within the concept a singular solution to be analyzed and interrogated; to be asked what a world saved by superheroes would look like.

It is safe to say that Moore found the answer, in the end, horrifying. In Moore’s eyes there is a rot intrinsic to superheroes; something about it which inevitably gives way to a terrifying cruelty. To use the tagline for another Supergods, “praying to a man who can fly will get you killed.” In Watchmen, the people look up and whisper “save us” and Ozymandias nukes them with a fake alien. The only alternative to this salvation is Rorschach’s psychopathic obsession and the chance actions of an incompetent errand boy for a right-wing tabloid. Superheroes are not the answer, but rather the problem. Moreover, however, they’re a very specific problem. The major divergence from established US history, aside from the perpetual reelection of Richard Nixon, is that Doctor Manhattan’s destabilizing effect on the Cold War, especially once he departs the Earth, ends up making it substantially less cold. In other words, the ultimate expression of the nuclear bomb is the living weapon. The implicit metaphor is made even more clear in Moore’s original description of the first panel, which was to accompany the iconic blood-flecked smiley with a package of “Meltdowns” candy, introducing the crucial theme of the atom bomb.

This theme is just as present for Morrison, however, albeit in a very different symbolic configuration. He opens Supergods by declaring that “four miles across a placid stretch of water from where I live in Scotland is RNAD Coulport, home of the UK’s Trident-missile-armed nuclear submarine force,” going on to talk about how his father was “arrested during the antinuclear protest marches of the sixties.” And this something that comes up a lot for Morrison. In the Talking With Gods documentary he discusses his upbringing, transitioning almost immediately from talking about the part of Glasgow he grew up in to talking about how his father was a World War II veteran turned pacifist, talking movingly about the intensiveness of his father’s activism, and about his formative experiences, as he puts it, being “used as a decoy” whereby he and his father would deliberately kick a ball over the fence of a military facility, then climb the fence to retrieve it, and, while they were at it, snap some photos. “I saw some really strange stuff when I was a kid,” he explains, “Prisoner-style things,” going on to talk about how some his father’s friends were vanished by the government for their political views.

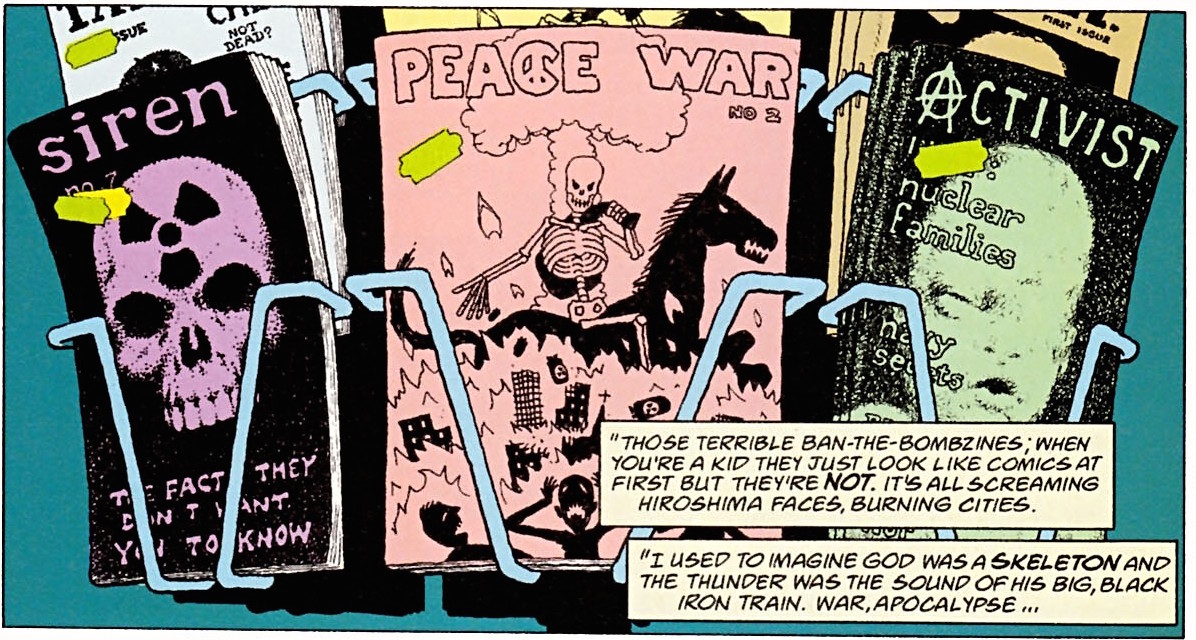

Unsurprisingly, the effect of this was that the atom bomb acquired a sort of totemic power for him. In the quasi-autobiographical Flex Mentallo, Morrison has a character relate an anecdote clearly drawn from his own childhood: “Was I telling you about those political bookshops my dad used to take me to? What was I saying? Those terrible ban-the-bombzines; when you’re a kid they just look like comics at first but they’re not. It’s all screaming Hiroshima faces, burning cities. I used to imagine God was a skeleton and the thunder was the sound of his big, black iron train. War, apocalypse… they were like comics from hell. It really fucked me up.” He relates a similar story in Supergods, talking about “the radical antiwar samizdat zines my dad brought home from political bookstores” whose “enthusiastically rendered carrion landscapes never overlooked any opportunity to depict shattered, obliterated skeletons contorted against blazing horizons of nuked and blackened urban devastation. If the artist could find space in his composition for a macabre, eight-hundred-foot-tall Grim Reaper astride a flayed horror horse, sowing missiles like grain across the snaggle-toothed, half-melted skyline, all the better.” And so, in the face of this existential dread, Morrison turned to superheroes, reasoning that “Before it was a Bomb, the Bomb was an Idea. Superman, however, was a Faster, Stronger, Better Idea. It’s not that I needed Superman to be ‘real,’ I just needed him to be more real than the Idea of the Bomb that ravaged my dreams.” For him in other words, superheroes are a means of liberation from the Bomb, not an inherent metaphor for it.

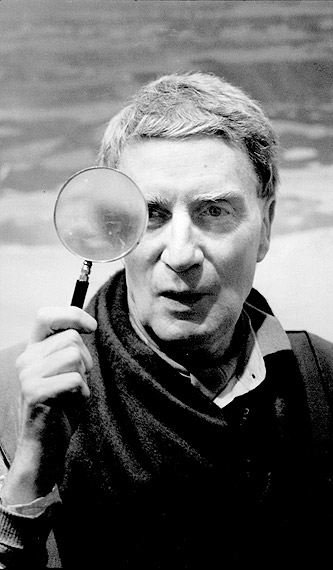

Moore was no less obsessed with the Bomb, of course; Watchmen is proof enough of that. But his relationship with it is fundamentally different. The Bomb was not a childhood monster for Moore; the great existential dread of his youth was the class divide, and it was the grim monocolor of the Boroughs that superheroes provided an alternative to, not the hyper-gothic spectacle of nuclear annihilation. For Moore, the focus on atomic weapons as a major anxiety came in the 80s, and coincided with the birth of his two daughters. The 1987 installment of England Their England focusing on Moore is revealing in this regard – Moore speaks of his desire to write about the dangers of the world specifically in terms of his children, discussing them with a charmingly bored-looking Leah and Amber sitting in his arms and explicitly noting that “I’m a parent myself.” As he puts it, “the world that we’ve been careless enough to leave laying around for our children to inherit is a place which is sometimes hostile,” and that “the only way I can help my children, the only real sort of chance that I can give them of securing their emotional and physical and psychological survival is to actually tell them about the stuff that’s going on in the world,” explicitly citing nuclear pollution as the sort of thing children should be told about. Later, at the documentary’s end, he muses in voiceover on the way in which the looming threat of nuclear annihilation changes society, suggesting that it makes a choice between armageddon and utopia stark and immediate, while the camera shows him walking through a park, joined by Leah and Amber, who he scoops up in his arms as the voiceover offers the documentary’s final words, “if somehow our children ever see the day in which it is announced that we do not have these weapons anymore, that we can no longer destroy ourselves and that we’ve got to come up with something else to do with our time, then they will have the right to throw up their arms and let down the streamers and let forth a resounding cheer.”

In many ways, this is the heart of the disagreement between Pax Americana and Watchmen. Morrison sees superheroes as creatures of immense possibility whose value is as aspirational figures. For him it is the interminability of superhero narratives that is most interesting – the fact that characters get reinvented over and over again, with new ideas and new takes, and that the stories never have to come to an end. Whereas to Moore, at least in Watchmen, what is interesting are the limitations of superheroes – of what they are incapable of doing and representing. The superheroes of Watchmen are known archetypes that the audience has seen a hundred times before, only taken to logical endpoints. The point isn’t the possibility of the characters, it’s the impotence of them. Put another way, Morrison cares what superheroes let us be, while Moore cares what they let us see.

This division, or at least the underlying division over what the purpose of art is, is one that will persist, in some form or another, throughout the War. But ironically, when it comes to the actual disagreement over the possibility of superheroes as an optimistic genre, it is Morrison’s view that ultimately won the day. Part of Moore’s ultimate revulsion at Watchmen was precisely the way in which, as he put it, it became “a kind of hair shirt that the super-hero had to wear forever after that… they’ve all got to be miserable and doomed. And if they’ve got to be psychopathic as well, then so much the better.” Indeed, Moore was adamant that “imaginative fiction,” and specifically superhero fiction, “is something which is perfectly fine for adults,” a point he attempted to demonstrate in much of his superhero work following his departure from DC.

Arguably, then, this forms one of the few major chinks in Moore’s usually resilient armor of eternity – a point on which Moore can decisively and unambiguously be said to have changed. And yet it is easy to overstate this. Moore’s revulsion towards Watchmen is genuine, and yet it is not really a revulsion at the work itself. Rather, it is a revulsion at the world that Moore used Watchmen to look at – one that he found monstrous and twisted, and wrongly assumed that the rest of the world would see it that way as well. This is not just a matter of the fans who seized onto Rorschach in ways Moore found disturbing, but rather the entire way in which the nightmarish world he constructed, in which superheroes were the embodiment of humanity’s most self-destructive impulses tragically deluding themselves into believing that they were the world’s Watchmen and not its doom, was treated as something desirable.

Arguably, then, this forms one of the few major chinks in Moore’s usually resilient armor of eternity – a point on which Moore can decisively and unambiguously be said to have changed. And yet it is easy to overstate this. Moore’s revulsion towards Watchmen is genuine, and yet it is not really a revulsion at the work itself. Rather, it is a revulsion at the world that Moore used Watchmen to look at – one that he found monstrous and twisted, and wrongly assumed that the rest of the world would see it that way as well. This is not just a matter of the fans who seized onto Rorschach in ways Moore found disturbing, but rather the entire way in which the nightmarish world he constructed, in which superheroes were the embodiment of humanity’s most self-destructive impulses tragically deluding themselves into believing that they were the world’s Watchmen and not its doom, was treated as something desirable.

It is, in other words, not Watchmen, nor even its treatment of superheroes that Moore turned away from, but rather an understanding of the world and his place in it. Up until Watchmen, Moore was able to believe in a basic confluence between the world he wanted and the world he lived in. He was, at that point, riding several years of steady ascent and success. Yes, there had been frustrations and fallings out with various collaborators and publishers along the way, but for the most part Moore would have had an entirely justifiable sense that his vision was something valued and embraced by the world. But in the wake of it, Moore realized something crucial and horrifying: he was, in practice, completely misunderstood. What the world desired was not his vision, but a misapprehension of that vision; one that cast him as the genius who would transform tired superhero narratives into their truer, darker form.

It was not, of course, Moore’s revulsion as such that caused his rift with DC. That was its own set of events. And yet his revulsion is inextricable from it; the same process played out in a slightly different arena. In one, it is an entirely aesthetic schism – Moore walking away from the style of comics he helped make popular. In the other, it’s just business – Moore feeling cheated one more time than his sense of honor among thieves could bear. But in both cases the basic issue is the same: Moore realized that he was badly wrong about the sort of world he was living in, and took typically bold and decisive action to deal with the problem. And in both cases, the fallout was enormous.

It was not, of course, Moore’s revulsion as such that caused his rift with DC. That was its own set of events. And yet his revulsion is inextricable from it; the same process played out in a slightly different arena. In one, it is an entirely aesthetic schism – Moore walking away from the style of comics he helped make popular. In the other, it’s just business – Moore feeling cheated one more time than his sense of honor among thieves could bear. But in both cases the basic issue is the same: Moore realized that he was badly wrong about the sort of world he was living in, and took typically bold and decisive action to deal with the problem. And in both cases, the fallout was enormous.

“She wasn’t anyone special. She wasn’t that brave, or that clever, or that strong. She was just somebody who felt cramped by the confines of her life. She was just somebody who had to get out. And she did it! She went out past Vega, out past Moulquet and Lambard! She saw places that aren’t even there any more! And do you know what she said? Her most famous quotation? ‘Anybody could have done it.’” – Alan Moore, The Ballad of Halo Jones

[It is not as though Brian Azzarello is a less skilled creator than Darwyn Cooke or Amanda Conner. He is one of several heavily noir-influenced writers to enter comics in the wake of Frank Miller, and is a skilled practitioner of the style (indeed, DC eventually tapped him to co-write The Dark Knight III: The Master Race). His best-known work, the Vertigo series 100 Bullets, is one of the classics of that imprint, a sprawling noir epic of vendettas and betrayals. And so his announcement as the writer of both Before Watchmen: The Comedian and Before Watchmen: Rorschach seemed, if not promising (given the general and deserved skepticism the project was met with), at least like as good a choice as was available. The Comedian and Rorschach were, after all, the two characters most thoroughly steeped in Watchmen’s darkness. Azzarello was an acclaimed noir writer. It seemed a match made, if not in heaven, at least in the office of someone who followed the Diamond sales charts closely.

[It is not as though Brian Azzarello is a less skilled creator than Darwyn Cooke or Amanda Conner. He is one of several heavily noir-influenced writers to enter comics in the wake of Frank Miller, and is a skilled practitioner of the style (indeed, DC eventually tapped him to co-write The Dark Knight III: The Master Race). His best-known work, the Vertigo series 100 Bullets, is one of the classics of that imprint, a sprawling noir epic of vendettas and betrayals. And so his announcement as the writer of both Before Watchmen: The Comedian and Before Watchmen: Rorschach seemed, if not promising (given the general and deserved skepticism the project was met with), at least like as good a choice as was available. The Comedian and Rorschach were, after all, the two characters most thoroughly steeped in Watchmen’s darkness. Azzarello was an acclaimed noir writer. It seemed a match made, if not in heaven, at least in the office of someone who followed the Diamond sales charts closely.

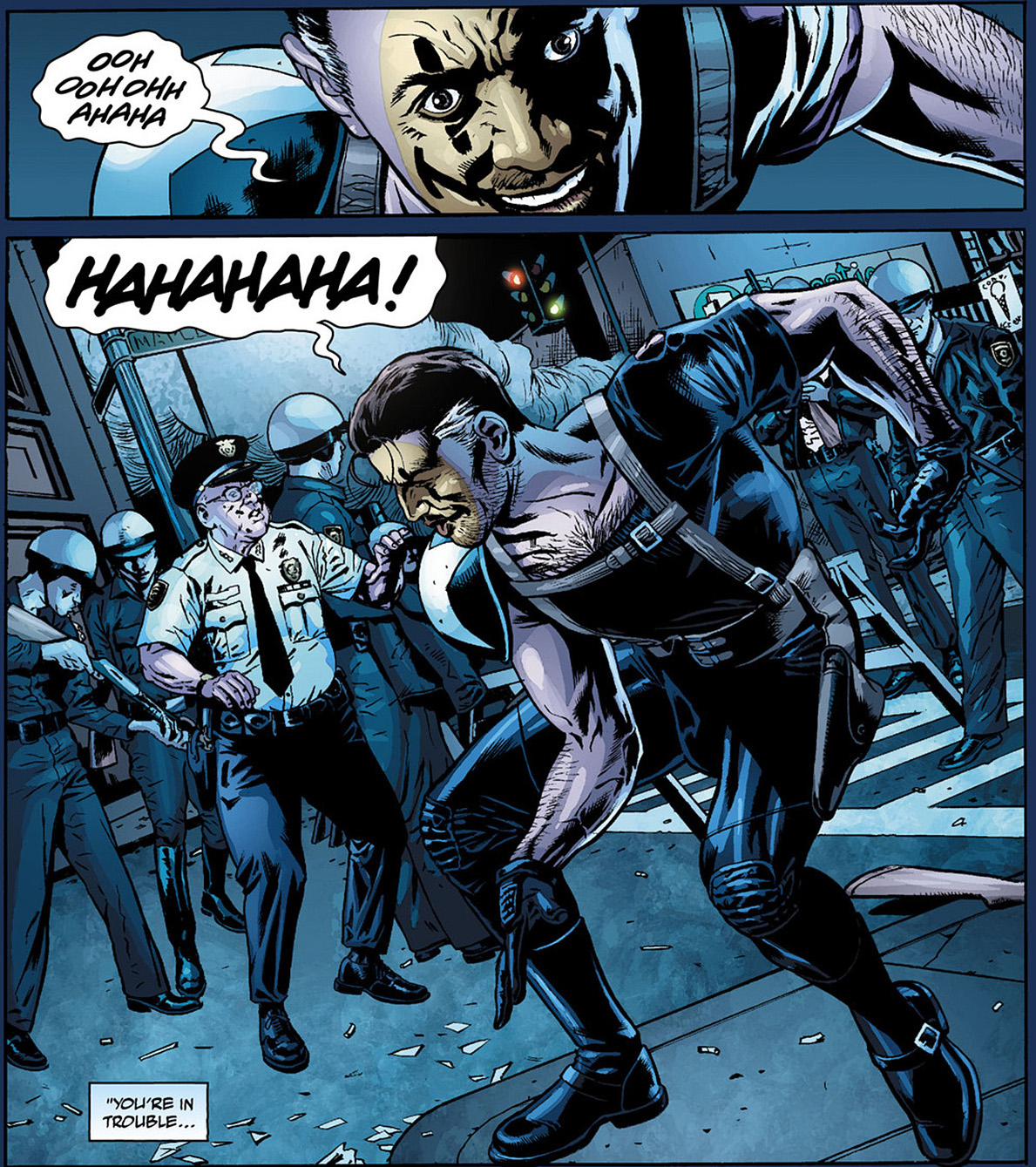

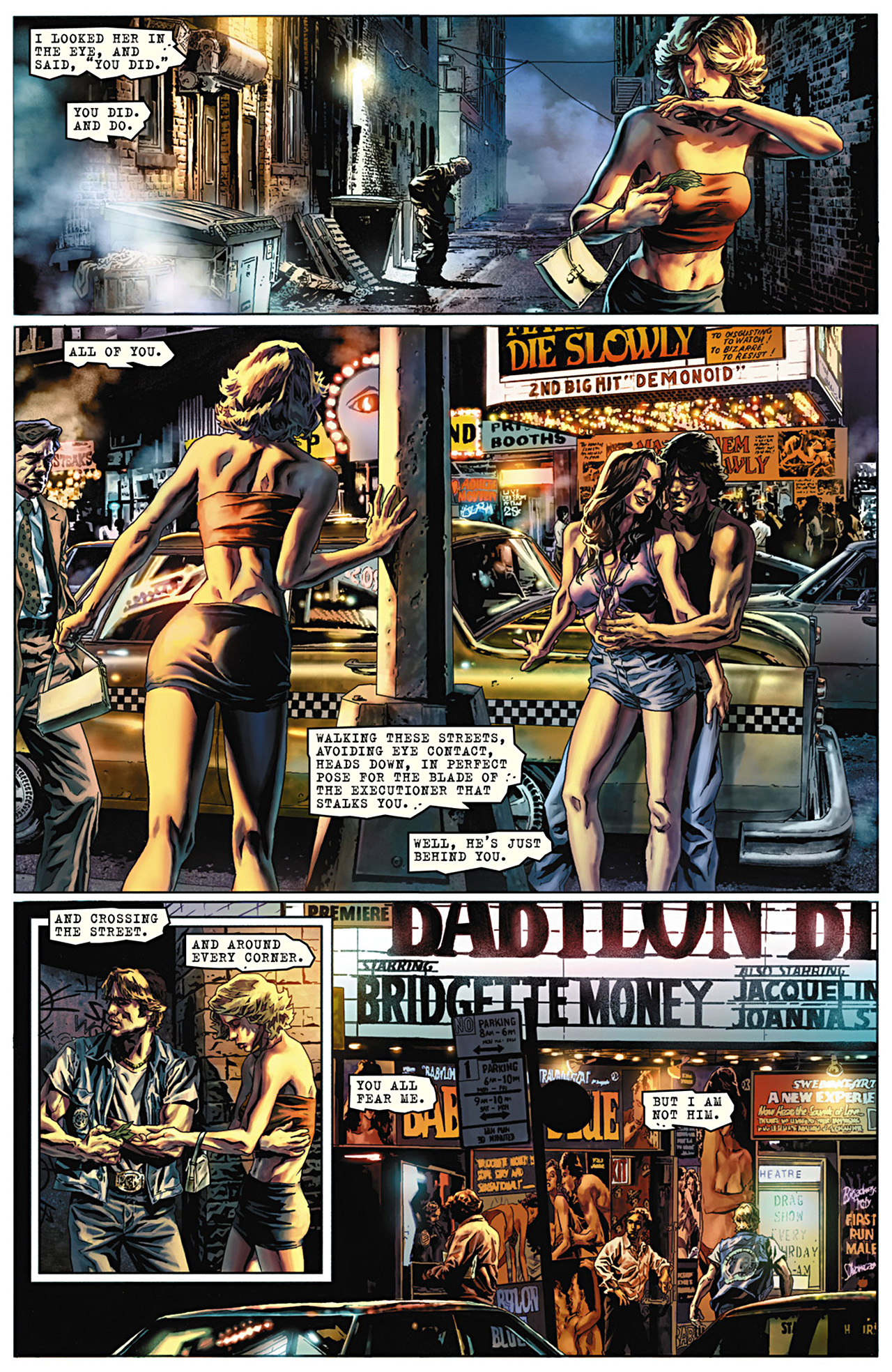

The problem is that Azzarello, although capable of impressive and thoughtful work, is also perfectly willing to just half-ass a job for the paycheck if he’s not particularly interested in it. And on the evidence, he was not especially interested in Before Watchmen. He flatly admitted in interviews that “it hasn’t been an easy project to work on, editorially,” and while he displayed some enthusiasm for Before Watchmen: Rorschach, which was the first title he was offered, his comments on Before Watchmen: The Comedian are relatively scant. Of course, reading the comic it’s not hard to see why he might be unenthused about it. All three of the Before Watchmen books to stretch out to six issues suffer for it, with at least one issue that’s completely unnecessary. In the case of Before Watchmen: The Comedian it’s the third issue (although the fourth and fifth could probably be consolidated into one without undue trauma), which leaves the series’ main plot (involving the Comedian’s activities in Vietnam) aside entirely in order to have the Comedian nip back to Los Angeles so he can get involved in the Watts riots.

The relative pointlessness of this third issue, however, pales in comparison with its basic level of sheer and unbridled awfulness. It is not so much the fact that the Comedian paints his face with his signature yellow smiley face in a grotesque and offensive parody of blackface before going to confront the rioters; this is indeed horrible, but it’s horrible in a way that’s mostly consistent with the character (although nothing in Watchmen ever has him being quite so petty). Rather, it’s the overall decision on Azzarello’s part to portray the worst of the riots as happening because of the Comedian’s intervention. Tellingly, the script specifically mentions the death toll – thirty-four – which is the same as the real-world riots. In other words, the event plays out exactly as it did in the real world – indeed, Los Angeles police chief William Parker’s infamous description of the rioters as “acting like monkeys in a zoo” appears in the comic as well (although the Comedian’s subsequent decision to hurl dog feces in his face while shouting “OOH OOH OHH AHAHA HAHAHAHA” is original to Azzarello’s version). This marks a fairly significant shift from Moore’s approach to the intersections of superheroes and real-world history, which, with one obvious exception, generally resulted in history being changed by superheroes (as with the resolution of the Vietnam War, which the US won in Watchmen due to the intervention of Doctor Manhattan) or superheroes having no visible effect on history (as with World War II, where, although the Comedian fought in the south Pacific, he seems to have had no particular impact on the war). Azzarello, on the other hand, takes real-world events that actually happened and rewrites them to be caused by superheroes. That these events were one of the most fraught moments of the 1960s struggle for black civil rights is even more tasteless, stripping away the material history that Watchmen was built on and replacing it with a crude simulacrum.

The one exception to this within Watchmen is the implication in issue #9 that the Comedian might have been involved in the assassination of John F. Kennedy. But, of course, this is largely a joke on Moore’s part; for one thing, it really is just a throwaway implication – it’s suggested quite strongly that the Comedian killed Woodward and Bernstein before they could break the Watergate scandal, and when this is brought up the Comedian denies it, but jokes, “just don’t ask me where I was when I heard about J.F.K.” For another, even if one does opt to read the Comedian as making any sort of sincere admission, it’s the JFK assassination, and the suggestion that the Comedian did it has to be read in light of the staggering number of conspiracy theories already surrounding that assassination.

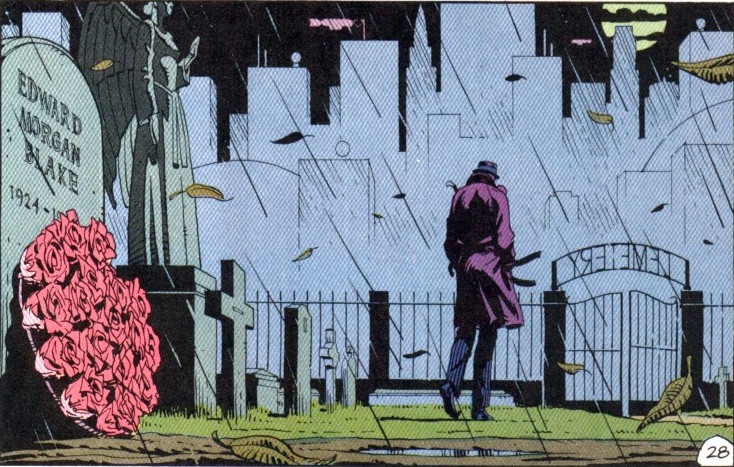

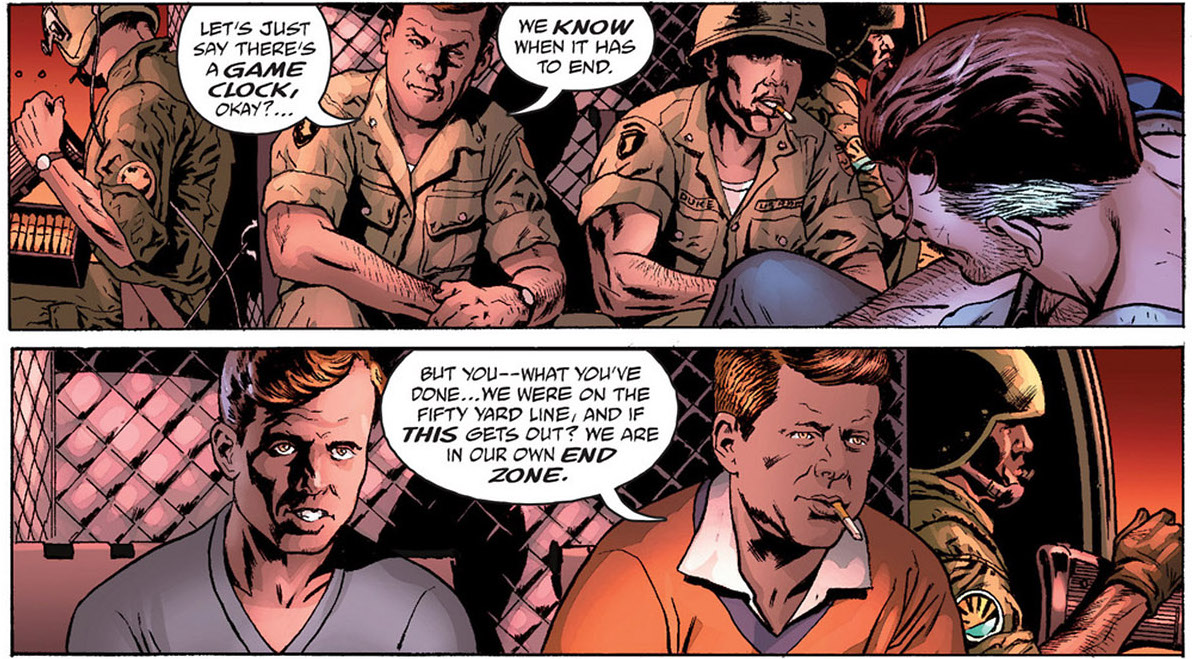

In this regard, Azzarello’s decision to make it unambiguously clear that the Comedian did not, in fact, kill JFK is hard to object to. Certainly it’s a much better decision than Zack Snyder’s opting to make it explicit that he did kill Kennedy. More questionable is his decision to have the Comedian and Moloch be so stunned by the news that they abandon their impending shootout to drink together in mourning. This extends out of a larger decision in the first issue to vividly portray the Comedian’s friendship with Kennedy, whom he to have been “a great man,” stressing to Jackie Kennedy the degree to which he respects the President. Indeed, one of the opening images of the comic is a recreation of the iconic “Kennedy brothers playing football” photo with the Comedian added to the game, making the Kennedy/Comedian link the foundational image the story is built on. This sets up the larger structure of the miniseries, which ends with the Kennedy assassination the Comedian is responsible for, namely RFK (he’s tipped off to the CIA’s plot involving Sirhan Sirhan by G. Gordon Liddy, and kills him at close range with the same kind of gun to keep Kennedy from revealing his involvement in a massacre in Vietnam).

It would be overstating the case to say that Azzarello simply allies the Comedian with Kennedy-style New Frontier liberalism: the ending makes that a hard sell, after all. Rather, it’s that Azzarello uses the two Kennedy assassinations as the poles in a fairly traditional account of the decline of 1960s leftist idealism, from JFK’s death as a tragedy that stuns the Comedian to RFK’s death as the Comedian’s own doing, with the engine of that transition being the Vietnam War. Azzarello does not do anything so crass as suggest that the Kennedys are some sort of unalloyed good, of course. He portrays them in line with the historical reality of their considerable corruption. But their corruption is ultimately paralleled with the Comedian’s; he even refers to Robert Kennedy as a “way more effective” crime fighter than he is at one point. They’re all of a type; the sort of morally compromised hard men who flooded superhero comics in the wake of The Dark Knight Returns, and that Watchmen is so often misunderstood as being about. This is even echoed in the art; J.G. Jones, doing his first significant interior work since his awkward exit from Final Crisis three years earlier, imbued the series with what Azzarello called a “masculine realism,” framing this sense of masculinity as central to the Comedian’s character.

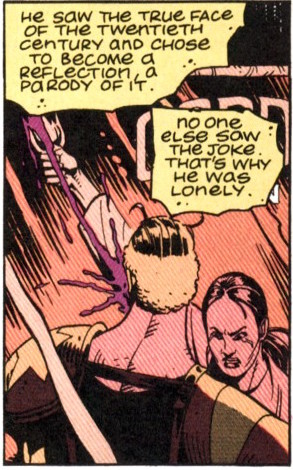

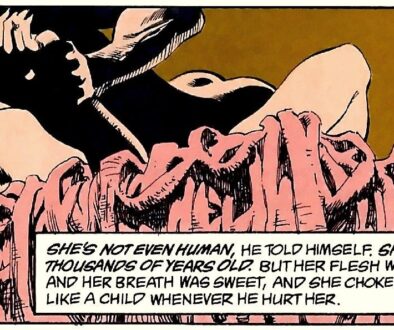

This is, to say the least, a bizarre take on the Comedian. Over and over again Watchmen stresses that the Comedian is essentially a nihilist; he understood the same existential darkness that Rorschach did, and, as Rorschach puts it, “chose to become a reflection, a parody” of the fundamentally dysfunctional and broken world. Unlike Rorschach’s absolute belief in justice, however, the Comedian was fundamentally amoral, ultimately driven only by a desire to be tougher than the world (hence his ultimate breakdown when he realizes that Ozymandias’s pragmatic nihilism vastly exceeds his own). Simply put, he’s almost fundamentally impossible to use as the symbol of any sort of idealism, even one in terminal decline. Azzarello’s character, who sulks that “the one thing – the abso-fucking-one thing that no one ever got about me is that I am a patriot” is, in this regard, virtually unrecognizable. As for the idea that the Comedian represents some sort of masculine ideal at any point in his career, it’s difficult to see where this comes from within Watchmen, where one of the first things established about the character is the fact that he raped the Silk Spectre.

Indeed, it’s really this issue over which the Comedian’s characterization falls apart. Azzarello’s story ultimately has his experiences in Vietnam (and particularly his experiences taking LSD in Vietnam) serve as, if not a loss of innocence (it’s not as though he has much at the start, after all), at least a decisive final step in the character’s downfall. But in Watchmen there’s no sense of this. The Comedian is already a violent rapist in the 1940s, and his view of the world as a joke is already well in place – that’s the entire point of his taunting response after Hooded Justice beats him, “this is what you like, huh? This is what gets you hot.” His story is not one of becoming or self-actualization; the entire point, in many ways, is that he’s the one character who never really changed from the 1940s to the 1980s, which is why his death works as the instigating event for the narrative. To add a moment akin to Rorschach’s investigation of the Blaire Roche kidnapping in which the Comedian crosses some fundamental line by killing RFK just doesn’t fit into his narrative, and, moreover, actively undermines it.

That Before Watchmen: The Comedian is lackluster, however, is perhaps unsurprising. It was, after all, very much the second choice series for Azzarello, and its six-issue length is a fairly fundamental and irreparable flaw. What is perhaps more surprising is that, for all of its flaws, it’s still wildly better than the series that got Azzarello on board the project in the first place, namely Before Watchmen: Rorschach. Indeed, it is in some ways difficult to fully comprehend exactly how the book went as badly as it did. With the other three more or less completely meritless Before Watchmen titles it is at least straightforward to understand all of the steps involved in creating awful comics. But Before Watchmen: Rorschach is bad in genuinely surprising and unexpected ways.