Mirkwood (I: The Woodland Realm)

- Name: Mirkwood, Greenwood, Eryn Galen (Sindarin: green wood), Taur-nu-Fuin (Sindarin: forest under night), Taur-e-Ndaedelos (Sindarin: Forest of the Great Fear), Eryn Lasgalen (Sindarin: greenleaf wood)

- Description: A huge forest that splits Wilderland in half, ranging from 200 to 300 miles east-to-west and about 600 miles north-to-west. Dwarfs eastern neighbors Erebor and the Iron Hills, which look like serfs levied with small plots of land. Surrounded by the Misty Mountains and Grey Mountains.

Encompasses the Forest River and Enchanted River, with the Celduin running through its eastern border. An Old Forest Road, Men-i-Naugrim, is lost by The Hobbit’s time, while an enchanted elf path remains. The Emyn-nu-Fuin, Dark Mountains, are roughly in its north-central region, south of the Woodland Realm of the Wood-elves.

In the south, the East Bight chomps into Mirkwood, creating the Narrows of the Forest. The southwest corner houses Dol Guldur, sometime-home of Sauron and the Nazgûl. The Forest River and an enchanted river also run through Mirkwood. - Locations in Peter Jackson films: Te Anau, South Island (Mirkwood Gate), Pelorus River, South Island (Forest River), Stone Street Studios (Thranduil’s caverns)

Less a geographic location than a metonym for Middle-earth’s unfinished tale, Mirkwood is a classic fairy tale forest that defines those forests. Its iconic appearance in The Hobbit which it profoundly changes is only one aspect of its story. Many characters and texts have their own Mirkwoods. This derivé will stray out of thought and time, and wander far on roads only we shall tell. It’s up to us to find a guide through it.

Mirkwood is too large and complex to be one thing. John D. Rateliff points out that Mirkwood marries “two archetypes: The Dark Wood and The Enchanted Forest.” Similarly, John Garth writes “Mirkwood is a portmanteau forest of forests.” Even the name “Mirkwood” is of early provenance, having been applied to a number of historical and legendary forests. Since its name doesn’t belong to only one place, Mirkwood exists in a state of identity crisis, with factions and traditions battling over their different visions of the forest.

In The Hobbit, Mirkwood has been effectively conquered by the gothic. The book shows Mirkwood as a divided primal forest with elements of gothic horror, so dark that it’s “not what you call pitch-dark, but really pitch.” The wood is festooned in “dark dense cobwebs with threads extraordinarily thick”, populated by “black moths, some nearly as big as your hand”, heretofore unknown butterfly species, and giant spiders. Bilbo and the dwarves walk among “dead leaves of countless other autumns.” It’s a Brothers Grimm-esque scary forest, the sort of place where stepping on the wrong plant could be fatal.

Where Tolkien innovates is that Mirkwood’s darkness is a symptom of sickness. Mirkwood is suffering from Sauron’s presence. In The Desolation of Smaug, Bilbo observes that Mirkwood “feels sick, as if a disease lies upon it.” The Necromancer, or Sauron, is a foreign presence plotting his return to prominence by poisoning verdant nature.

Prior to The Hobbit, the forest is Greenwood the Great, which Gandalf calls “the greatest of the forests of the Northern World.” Greenwood is home to Wood Men, a local group who’s largely offstage, and Wood-elves who establish their Woodland Realm in the northern forest. When Sauron begins hurting the forest, the Five Wizards begin their work in Middle-earth. In a way, Greenwood is The War of the Ring’s first battleground.

This war is ecological: the Wood-elves and the Wizards fight for an almost Germanic Greenwood with healthy wildlife and green leaves, while Sauron turns Greenwood into a gothic wood. “Who owns the land?” is a philosophical question. Middle-earth’s lands are affected by who occupies them. Blonde, pale beauties create a tenuous peace with nature, while Sauron, a refugee from the East, seeks to conquer it.

This union of healthy land and racial occupation has clear reactionary overtones. We’ll discuss Sauron more next essay, so let’s focus on the Wood-elves for now. The Woodland Realm reflects the elves who live there. The elves make the forest’s paths, which in their vicinity is flanked by “endless lines of straight grey trunks like the pillars of some huge twilight hall,” illuminated by “a greenish light.”

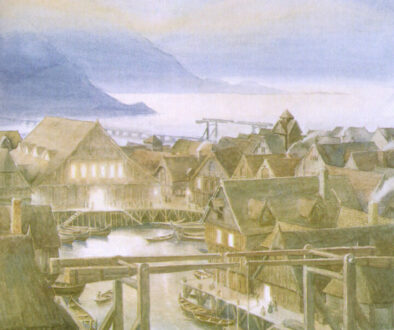

The Woodland Realm’s positioning in a valley distinguishes it. Thranduil has an underground kingdom in a cave, with “many passages and wide halls,” while his subjects live in “houses or huts on the ground and in the branches.” The land reflects a clear yet strange hierarchy: Thranduil and his Sinda family rule their above-ground Silvan citizens from an underground cave. Like Erebor, the Woodland Realm bolsters its power by ruling from below.

Nowhere and Back Again has gone more than 40,000 words without talking about elves very much, instead focusing on more marginalized populations. So it’s fitting that they enter our story with its more taciturn members. The Elves of Mirkwood aren’t High Elves, but introverts hiding from their relatives and other peoples. Their fashy overtones as white avatars of nature is complicated by their faerie nature, a fact Tolkien highlights by invoking Faerie in describing them. They’re triumphant avatars masquerading as the repressed, yet they rank low in Arda’s elvish hierarchy.

It’s worth exploring the Mirkwood Elves’ role in Middle-earth’s history. They are Silvan Elves, descendants of the Teleri, not one of Tolkien’s favorite groups, ruled by the Sindar, or Grey-elves, who disobeyed the Valar’s call to return to Valinor. In The Lord of the Rings, they’re practically exiles, doomed to decline with Middle-earth.

So their relationship to the earth is telling. The Wood-elves have a symbiotic relationship with Mirkwood, so they can hunt its fauna and clear some of its trees for their nourishment and comfort, unlike Sauron, who conquers nature. A few deer and some trees are Mirkwood’s payment for the elves’ survival. Socially, the Woodland Realm is Mirkwood, the place where these elves belong.

The Wood-elves have a particularly bad time of it. They cordon themselves off from both their relatives in Lothlórien and Moria’s Dwarves, settling in northern Mirkwood. Their king Oropher dies in the Last Alliance of Men and Elves, alongside roughly two thirds of Mirkwood’s forces. His family’s mistrust of others is a historical phenomenon, while his son Thranduil’s xenophobia clear extends from trauma.

The Elven-king Thranduil exemplifies his people’s “distrust of strangers” and insular relationship with nature. He’s not a villain, a fact The Hobbit stresses by insisting that “these are not wicked folk.” He’s more a force of nature, ambivalent to the dwarves’ quest and primarily concerned with protecting his people. Thranduil does inherit his ancestor’s antipathy to dwarves — hostility between dwarves and elves is a minor subplot in The Lord of the Rings. When he angrily asks Thorin “what were you doing in the forest?”, Thranduil is both offended and afraid for his people’s safety.

In the end, Thranduil does fight for his people and others. He defeats Sauron’s troops in Mirkwood and restores the forest with Celeborn. But he’s basically exempt from connecting with other characters. In The Hobbit he’s simply “the Elven-king,” while he’s completely offstage in The Lord of the Rings.

It’s worth noting that the text’s ambiguity about Thranduil leads to drastically opposed portrayals of him. Lee Pace plays Thranduil as a gloriously camp and metrosexual little bitch, while Rankin-Bass makes him a green abomination voiced by Austro-Hungarian director Otto Preminger. The Hobbit films make Thranduil a disfigured veteran of wars with dragons and a grieving widower who fails to love his son Legolas. His mystique masks vulnerability, something queer actor Lee Pace plays tremendously well.

Yet Thranduil’s petty bitchery does not give us a path through Mirkwood. He belongs to the forest too completely, particularly Mirkwood in The Hobbit’s time. Let’s explore another candidate for a guide through Mirkwood.

Tauriel is the Peter Jackson film series’ only original major character. Her mixed reception is a complicated matter: there’s clearly misogyny in fans’ backlash to her character, and yet she genuinely doesn’t work. Screenwriters Philippa Boyens and Fran Walsh’s conservative feminism, which boils down to “I’m not like other girls”, does little to make Tauriel feel like she belongs in the story, while Tauriel’s studio-mandated love triangle that violated the terms of actress Evangeline Lilly’s casting renders The Desolation of Smaug incoherent. Still, the addition of a female character to the extremely androcentric Hobbit is an essentially good idea, so let’s see if we can elf-ladyboss our way through this forest.

There are some ideas that work off the bat. Tauriel is Silvan, which puts her at the Sindarin Thranduil’s beckon call and complicates her relationship with Legolas. As a woman and a Silva in a male-dominated Sindarin kingdom, she’s low in the elvish hierarchy. Her relationship with Kíli (not actually a bad idea, although its ideal state would be a not-explicitly-romantic arrangement that the perennially sentimental Jackson is incapable of shooting) shows a way out of Mirkwood, as does Tauriel’s banishment by Thranduil. She exists outside the elf-lady mold of Galadriel and Arwen, something Tolkien never offers in his work. On paper, Tauriel is a much needed feminine salve to Middle-earth’s masculinity.

The problem is that Tauriel was always going to be a patch rather than her own character. She was always going to stick out as “the character who’s not in the book” when the Hobbit trilogy was already struggling to win over people who just wanted one film. That screenwriters Fran Walsh and Philippa Boyens subscribe to a conservative feminism where an upper-class lady who’s beholden to can be a badass simply by picking up a sword doesn’t help her either. Tauriel tries to cut her way through Mirkwood’s brambles, but she’s stuck in her films’ already convoluted notion of what it should be.

This leaves us with only one elf who can guide us out of the Woodland Realm. Legolas is far from a significantly developed character, more notable for being a taciturn entity in the books than any of his companions. In Unfinished Tales, Tolkien gives poor Legolas a hard time, saying

In Sauron’s final overthrow, Elves were not effectively concerned at the point of action. Legolas probably achieved least of the Nine Walkers.

Since the elves are on their way out in The Lord of the Rings, they need to find a new way to exist. Legolas’s relatively minor role in the book is a graceful concession of defeat. Unlike Thranduil, Legolas is not a kingpin: he is part of the company.

A vital aspect of Legolas’ presence is his relationship with Gimli. Regardless of Tolkien’s intentions (although given his relationship with C. S. Lewis, he probably wasn’t terribly cognizant of them), Gimli and Legolas have a queer relationship, bickering like a frustrated couple, seeking each other out in battle, and ultimately going to the Undying Lands together.

The last part is particularly important, as Gimli is the only dwarf to sail west. Tolkien clearly didn’t write an intentionally romantic relationship, but it’s difficult to think of a more romantic gesture than Legolas breaking the natural order for Gimli. It has some of the same cadences of Beren and Lúthien, for Eru’s sake. The Lord of the Rings even says that when Legolas and Gimli’s “ship passed an end was come in Middle-earth of the Fellowship of the Ring.” A queer interracial couple has the last word.

So Legolas shows an elvish Mirkwood that’s ecumenical. His is one of many Mirkwoods, but it’s notable that even he leaves the forest. Greenwood and Eryn Lasgalen simply don’t have the enchanting power of Mirkwood. For all that Mirkwood is rooted in its own lack of certainty, its most compelling version is the haunted one in The Hobbit. Legolas can only carry us so far. So let’s explore the gothic side of Mirkwood, the reason the forest has its name, once again straying out of thought and time to paths few can tell us.