Mirkwood (II: Rhosgobel)

- Names: Rhosgobel (Sindarin?: “brown village”, or “russet town/enclosure”)

- Description: Rhosgobel is wizard Radagast the Brown’s home “near the borders of Mirkwood.”[1] It appears to be a house or enclosure, although Tolkien doesn’t describe it very much. Given Radagast’s proclivity for wildlife and particularly birds, we can assume Rhosgobel is a weird hippie aviary. By the end of The Lord of the Rings, Radagast has vacated Rhosgobel.

- Filming locations: Stone Street Studios, Miramar, Wellington, North Island

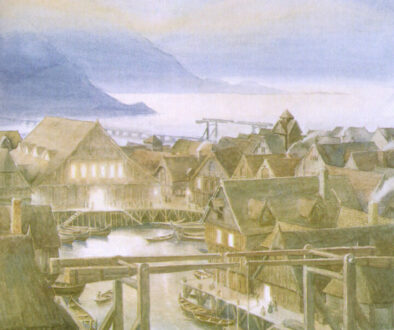

Rhosgobel, the wizard Radagast’s homestead, lies on “the forest borders between the Carrock and the Old Forest Road.”[2] Tolkien includes few other details about it. Unfinished Tales glosses Rhosgobel as “russet enclosure,” suggesting that it’s private land. The wizard’s lair refuses to be described.

Its occupant, Radagast the Brown, is the wizard Francis of Assisi, “a master of shapes and changes of hue” who “has much lore of herbs and beasts, and birds are especially his friends.”[3] Radagast is more reclusive than his fellow wizards Gandalf and Saruman, although he may be more outgoing than the Blue Wizards, two permanently offstage pieces of trivia. Rhosgobel’s positioning near Mirkwood lets Radagast watch for Sauron and monitor the forest’s decline, as well as be close to nature.

Radagast is one of the Istari, or Five Wizards, whom the Valar send to Middle-earth “to move Elves and Men to beware of their peril”[4] from Sauron. The wizards’ career begins at Mirkwood, meaning Radagast is the most ideally placed to monitor it. Like all the other wizards except Gandalf, Radagast strays from his charge, preferring birdwatching to sorcerer-fighting. At the Council of Elrond, Gandalf says when he convenes with Radagast, “he is one of my order, but I had not seen him for many a year.”[5]

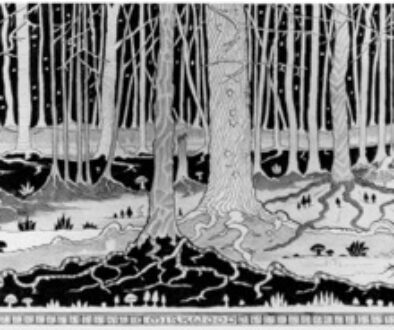

With Radagast, Tolkien explores the trope of a wizard as a hermit. The Hobbit film trilogy emphasizes this, showing Rhosgobel is a house with a tree growing through it, metastasizing into a mess of tangled branches and roots across its wooden floors, surrounded by magical paraphernalia. Artist Alan Lee cites author T. H. White’s depiction of Merlin in The Sword in the Stone as an influence. John Garth points out that Radagast almost shares a name with the Slavic god Radegast, putting him in a tradition with the Carpathian Mountains and Slavic Dracula.

We can’t talk about the Hobbit trilogy without discussing Sylvester McCoy’s portrayal of Radagast. We’re Eruditorum Press, so we can’t escape McCoy’s connections to Doctor Who, where he played the mercurial Seventh Doctor. Like Radagast, the Seventh Doctor sticks to the margins, playing observer more than actor, although the Doctor is sinister in a way Radagast couldn’t dream of being. Similarly he falls into cosmic plans, but again, Radagast never takes the Doctor’s Machiavellian path.

McCoy plays both characters as slightly cheeky but deceptively insightful, although unlike the Doctor, Radagast allows birds to nest under his hat and has bird shit caked on his face, a detail whose absence from Doctor Who is clearly a flaw. It helps that the Hobbit trilogy has Radagast drive a rabbit-drawn sled, allowing McCoy to deliver the amazing line “these are Rrrrhosgobel rrrrabits!”

A scene where Radagast resurrects a hedgehog named Sebastian, possessed by the corrupted Mirkwood, lends the character a dark gravity Tolkien never gave him. In the movie, Radagast tips off Gandalf to the Necromancer’s occupation of Dol Guldur, and discovers Mirkwood’s ruinous effects on its wildlife. An Unexpected Journey uplifts Radagast, turning Tolkien’s character into one of the trilogy’s most interesting and exhilarating aspects.

The films draw from the book’s implications here. In The Lord of the Rings, Radagast is charmingly ambivalent, a classic villainous wizard like Saruman or a Merlin-cum-Odin such as Gandalf, who simply refuses to be a major character in this literary epic. His major plot function is to screw up, as he inadvertently helps Saruman capture Gandalf by sending the latter to Isengard. It’s an honest mistake — Radagast tells him “I have an urgent errand,” and is genuinely invested in fighting Sauron. The last time Gandalf sees Radgast, he tells him “send out messages to all the beasts and birds that are your friends” to spy for the wizards.

Decidedly and willfully a lesser wizard, Radagast falls purposefully into obscurity. He seems to forget that he’s an angelic being deployed to Middle-earth for the sole purpose of fighting evil. The Fellowship of the Ring visits Rhosgobel after setting out from Rivendell, only to find that “Radagast was not there.”[6]

Yet Radagast strays from his path without turning to evil. Gandalf praises Radagast’s moral character, saying that Radagast “knew no reason why he should not do as I asked; and he rode away towards Mirkwood where he had many friends of old.” Radagast even gets the eagles to spy for him, and as everyone knows, they wouldn’t even cut out a year of everyone’s life by flying to Mordor. He’s not simply a good wizard in a moralistic sense; he’s good at being a wizard.

Unlike the Wood-elves or Sauron, who try to exert authority over wildlife, Radagast becomes part of it, wholly falling in love with the material world he’s supposed to look after. He seems apathetic to human culture, living in an enclosure and disparaging the hobbit homeland’s “uncouth name of Shire.” As a wizard, he’s more interested in monitoring the land and belonging to its creatures than in ruling it.

Perhaps Radagast’s chilly relationship with the Maia family drives him into seclusion. His simple predilections wins him scorn from Saruman, who disparages “Radagast the Bird-tamer! Radagast the Simple! Radagast the Fool!” The insults aren’t unfounded (or unhilarious, frankly). Radagast and Saruman have a chilly relationship from the beginning. The latter only brings the former to Middle-earth because Yavanna, the Vala Queen of Earth, “begged him.” The gods literally handpick Radagast to be a wizard. Maybe dashing through Mirkwood is how he embraces that privilege.

The wizards become active in Middle-earth when Sauron darkens Mirkwood, so the War of the Ring effectively starts with the arrival of Radagast and his fellow wizards. Radagast is like an anti-hobbit: a cosmically important figure who becomes a stay-at-home bumpkin.

Tolkien unfairly says that Radagast “did not remain faithful to his mission.”[7] Radagast fulfills his responsibilities to the Valar and Maiar while using them as stepping stones to his real project of belonging to nature. Like a hobbit, he sets out to defend the lands where he lives — but unlike them, he wholly submits to his environment. He fights Sauron, but has simpler, nobler priorities, like chilling the fuck out at Rhosgobel and talking to birds.

- [1] The Fellowship of the Ring, “The Council of Elrond”

- [2] Unfinished Tales, “The Istari”

- [3] “The Council of Elrond”

- [4] “The Istari”

- [5] “The Council of Elrond”

- [6] The Fellowship of the Ring, “The Ring Goes South”

- [7] Ibid

June 17, 2022 @ 1:42 pm

Tolkien unfairly says that Radagast “did not remain faithful to his mission.”[7] Radagast fulfills his responsibilities to the Valar and Maiar while using them as stepping stones to his real project of belonging to nature. Like a hobbit, he sets out to defend the lands where he lives — but unlike them, he wholly submits to his environment. He fights Sauron, but has simpler, nobler priorities, like chilling the fuck out at Rhosgobel and talking to birds.

Tolkien’s usually good at stacking the deck so that his tendencies towards divine command authoritarianism line up with “actually doing good things”, but this is definitely one of the thornier aspects of that. Could Radagast have raised an army of bears and harassed the garrison of Dol Guldur? Yes. Could he have run his own avian spy network straight from the beginning? Also yes (and actually that might be somewhere he failed; talking to and learning from animals is entirely within his wheelhouse). But there are other concerns, other actions to take, no less necessary, and Radagast rejects anthropocentrism (Eruhinicentrism?) because someone has to learn and understand (as much as one person can understand all the numberless perspectives we collapse into simple Nature).

Incidentally, I think you’re missing something from this sentence: In The Lord of the Rings, Radagast is charmingly ambivalent, a classic villainous wizard like Saruman or a Merlin-cum-Odin such as Gandalf, who simply refuses to be a major character in this literary epic. It looks like there should be something like “neither” before “a classic villainous wizard…”?

May 25, 2023 @ 9:38 pm

“did not remain faithful to his mission” = J.R.R.Tolkien does not say that. Those are Christopher Tolkien’s words, in his notes.