Barad-dûr

Names: Barad-dûr (Sindarin: “dark tower”), Lugbúrz (Black Speech: “dark fortress”), Taras Lúna (Quenya: “dark tower”), Lúnaturco (Quenya: “Dark Stronghold”)

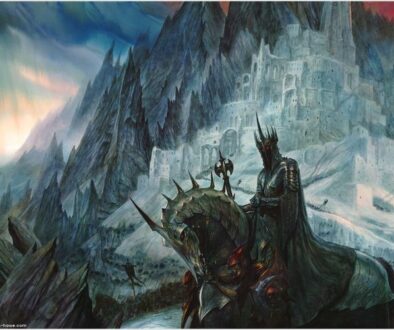

Description: a gargantuan fortress near the Ered Lithui (Ash Mountains), on the northern Plateau of Gorgoroth in Mordor, approximately 30 miles east of Mount Doom. Our trek has led us across Gorgoroth, an arid but fiery wasteland choked with ash and cinders. Built as a revival of the spirit of Morgoth, the primeval force of caprice and destruction in Middle-earth, Barad-dûr is a morass of towers and pits, perched in the heart of Gorgoroth, itself a throne for the Eye of Sauron, which surveys the world around it. One of Tolkien’s most iconic creations, it serves as an indomitable paean to Sauron’s power and the architectural body of Sauron himself in Peter Jackson’s film trilogy.

An often-observed aspect of Sauron is that while he’s The Lord of the Rings’ titular character and antagonist, he is a functionally invisible figure. He lacks a consistent physical body, has no dialogue, is only seen in characters’ visions or through great distances, and can hardly be said to be a character so much as a cipher of Middle-earth’s iniquities and caprice. For all intents and purposes, Sauron is cipher rather than a person, defined by his presence alone, having long abjected personhood to incarnate as a shapeless mass of power and domination, extant only for the decadent excesses of power and kept alive purely through those trappings.

The details of this are characteristically vague. Tolkien, a more esoteric writer than his reputation might suggest, is reticent on whether Sauron has a physical body. The perennially unfinished mythology of Middle-earth offers conflicting accounts of Sauron’s body. In the Akallabêth, The Silmarillion’s account of Númenor’s fall, the great kingdom of Men, Sauron is said to lost his primal holy form and constructed his own visage in Mordor, like a terrifying cherub going through a hardcore punk phase:

But Sauron was not of mortal flesh, and though he was robbed now of that shape in which he had wrought so great an evil, so that he could never again appear fair to the eyes of Men, yet his spirit arose out of the deep and passed as a shadow and a black wind over the sea, and came back to Middle-earth and to Mordor that was his home. There he took up again his great Ring in Barad-dûr, and dwelt there, dark and silent, until he wrought himself a new guise; and the Eye of Sauron the Terrible few could endure.

In “Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age”, Tolkien provides a similar, if even more abstract account of Sauron’s physical form:

[In Mordor] now [Sauron] brooded in the dark, until he had wrought for himself a new shape; and it was terrible, for his fair semblance had departed for ever when he was cast into the abyss at the drowning of Númenor. He took up again the great Ring and clothed himself in power; and the malice of the Eye of Sauron few even of the great among Elves and Men could endure.

Tolkien’s portrait of Sauron amounts to departure from material personhood. What identity he has left is fragments, obviated and consumed by avarice and sheer hunger for power. Like the Nazgûl after him, his primal identity vanishes as he erases it bit by bit.

This narrative of disappearance comes to a head with Sauron’s ostensible death at the hands of Isildur, when Sauron loses the One Ring, at which time he “forsook his body, and his spirit fled far away and hid in waste places; and he took no visible shape gain for many long years.” As he “let a great part of his owner former power” manifest in the Ring, it could be said that the Ring is Sauron’s body, serving as a great part of his physical form. In a frankly gut-busting letter to Catholic bookstore owner Peter Hastings in which Tolkien castigates Hastings for taking The Lord of the Rings too seriously, Tolkien elaborates on his theodicy as expressed through Sauron:

“…At the beginning of the Second Age [Sauron] was still beautiful to look at, or could still assume a beautiful visible shape — and was indeed not wholly evil, not unless all reformers who want to hurry up with ‘reconstruction’ and ‘reorganization’ are wholly evil, even before pride and the lust to exert their will eat them up.

Letter 153, The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkienz

Threats to the natural law make up the core of Tolkien’s theodicy. Morgoth’s original sin was throwing off the creator Ilúvatar’s genesis song by introducing harsh noise into the mix. Yet Sauron’s manifestation is sheer power, a mass of towers and military assaults and political allegiances. He takes the trappings of royalty and power for himself with none of the holiness of, say, Aragorn or Théoden. As a great lord of Middle-earth, Sauron fills the same role as the Lords of Men. Structurally, he possesses power and strives to secure it, merely doing so from a cultural position diegetically opposed to that of Gondor. Just as importantly, he appears to have some husk of a body, as Gollum seems to infer to Frodo:

‘It was Isildur who cut off the finger of the Enemy’ [said Frodo]. ‘Yes, He has only four on the Black Hand, but they are enough,’ said Gollum shuddering.

The Two Towers, Book IV, Chapter III: “The Black Gate Is Closed”

Gollum’s testimony to Sauron’s form only hints at Sauron’s physical nature (which might entail having a hand in Gollum’s torture), but it’s enough to suggest that Sauron is a husk of his former self, retaining some vestige of his previous form until his spirit is blown away when Gollum destroys the One Ring. Gollum is the only visible character in The Lord of the Rings who’s seen the interior of Sauron’s Dark Tower. In a way, Gollum is the character closest to Sauron, having worn his Ring for centuries and been reduced to a husk of his former self.

We’re nearly 1000 words into this essay and I’ve only just started to talk about Barad-dûr, despite it being the blog post’s eponymous location. This was intentional on my part. Barad-dûr is less a building where concrete events happen than it is a paragon of evil in Middle-earth. Tolkien’s only consistent descriptions of it are broad political ones in The Silmarillion and visions of epochal horror in The Lord of the Rings. There are no sequences of events that take place inside Tolkien’s legendarium, and adaptations of it largely follow suit (with the partial exception of a fleeting moment in Peter Jackson’s The Fellowship of the Ring, which we’ll get to later). Gollum’s experience of Barad-dûr is only mentioned, a feature both of Barad-dûr’s evasion of material reality and Gollum’s inability at coherent communication.

And yet for its recondite nature, Barad-dûr is the culturally defining architectural piece in The Lord of the Rings. The Eye of Sauron, which festoons the earliest hardback editions of the trilogy, sits atop the Dark Tower, an eldritch monstrosity too awful for stories of its own to permeate the larger narrative of Middle-earth. Its presence is at the center of some of Tolkien’s most memorable passages. Take for instance the moment at the end of The Fellowship of the Ring where Frodo, shaken by Boromir’s attempt to murder him, succumbs to temptation and dons the Ring, an event in which he is greeted by a terrifying vision of Barad-dûr:

Thither, eastward, unwilling [Frodo’s] eye was drawn. It passed the ruined bridges of Osgiliath, the grinning gates of Minas Morgul, and the haunted Mountains, and it looked upon Gorgoroth, the valley of terror in the Land of Mordor. Darkness lay there under the Sun. Fire glowed amid the smoke. Mount Doom was burning, and a great reek rising. Then at last his gaze was held: wall upon wall, battlement upon battlement, black, immeasurably strong, mountain of iron, gate of steel, tower of adamant, he saw it: Barad-dûr, Fortress of Sauron. All hope left him.

The Fellowship of the Ring, Book II, Chapter X: “The Breaking of the Fellowship”

And suddenly he felt the Eye. There was an eye in the Dark Tower that did not sleep. He knew that it had become aware of his gaze. A fierce eager will was there. It leaped towards him; almost like a finger he felt it, searching for him. Very soon it would nail him down, know just exactly where he was.

Tolkien doesn’t give Barad-dûr an in-depth description as a place; he’s disinclined to describe the appearances of his characters and locations. Rather he conveys the presence of Barad-dûr, the essence of total awfulness in Mordor. The Dark Tower is the stuff of apocalyptic visions, a marker of changing times. Indeed, the most explicit appearances of Barad-dûr in The Lord of the Rings are harbingers of massive changes in the narrative. In The Fellowship of the Ring, it signifies an end to the first part of Frodo’s quest and his departure from the Company that set out from Rivendell. A similar passage occurs after the One Ring is destroyed, this time from the perspective of Sam Gamgee, witnessing the Tower’s downfall through a traumatized haze:

A brief vision [Sam] had of swirling cloud, and in the midst of it towers and battlements, tall as hills, founded upon a mighty mountain-throne above immeasurable pits; great courts and dungeons, eyeless prisons sheer as cliffs, and gaping gates of steel and adamant: and then all passed. Towers fell and mountains slid: walls crumbled and melted, crashing down; vast spires of smoke and spouting steams went billowing up, up, until they toppled like an overwhelming wave, and its wild crest curled and came foaming down upon the land.

The Return of the King, Book VI, Chapter III: “Mount Doom”

Even in defeat, Barad-dûr signifies power and excess, its destruction seeming to last for eons as the gargantuan fortress collapses onto the Plateau of Gorgoroth. As the distance between Barad-dûr and Mount Doom, where Sam stands when he witnesses Barad-dûr’s fall, is no small one, we’re left with a sense of geography and apocalypse, where the death of societies is observable and concrete yet distant and hostile. Sauron’s fall can be witnessed by those who look for it, but it’s abstruse to those who haven’t been subsumed into his empire.

In Peter Jackson’s film trilogy, Barad-dûr’s presence is more ubiquitous than its literary counterpart. Part of this is down to the medium — an offstage protagonist is more manageable in prose than on film. Having montages conclude with shots of the Eye of Sauron is an effective way of conveying menace, and appropriately festoons the movies. Peter Jackson’s stylistic heavy-handedness is also a major fact in the pronunciation of Sauron’s presence in the films: would The Lord of the Rings have been a major Hollywood blockbuster with an 8-minute prologue featuring Sauron coming out in proto-Dark Soulsesque armor and beating the shit out of armored elves and men? From there Sauron’s presence is reduced to his (ultimately more memorable) Eye, glaring out over Middle-earth while retaining a physical presence. In The Return of the King, Jackson’s tendency for literalism manifests in the Eye casting a literal spotlight on the land around it, and that’s the extent of Sauron as a physical presence (barring a rightly deleted scene where Aragorn has a one-on-one sword battle with Sauron).

Barad-dûr is a stunning feat of design in the movies; one of the most alarmingly solid creations in it. A spiraling gothic mass of towers and spires, it’s crowned by Sauron’s Eye flaming above it watching the landscape. Yet we never get an interior shot of Barad-dûr, save a glimpse of Gollum on the torture table. Jackson’s Barad-dûr is ostentatious in its recondity, towering over the film, too evil to be explored in anything but its effects. The cast of The Lord of the Rings spend their lives responding to Mordor; the War for the Ring is ultimately waged on Mordor’s terms. Whoever tells the story, Tolkien or Jackson, none can escape the Dark Tower’s ubiquitous void.

April 16, 2021 @ 12:45 pm

Jackson’s tendency for literalism manifests in the Eye casting a literal spotlight on the land around it

It’s clangingly blunt in execution, but in fairness to Jackson, the image has firm foundations in the text, in the description of the Eye just missing Frodo on Amon Hen (“A black shadow seemed to pass like an arm above him; it missed Amon Hen and groped out west, and faded”) and in Sam’s other glimpse of the Tower (“as from some great window immeasurably high there stabbed northward a flame of red, the flicker of a piercing Eye”).

(As ever, the association or interchangeability of Sshadoww Andd Fllame /ChristopherLeevoice)

I was always slightly perplexed by how we know that Sauron possesses a device for just the kind of remote viewing he engages in, the palantir, and yet the operation of the Eye seems to be unrelated to it, as suggested by that quotation about what Sam sees and, even more, the mention shortly beforehand of “the Window of the Eye” (implying a gaze directed in some vaguely conventional way outwards, not into a crystal ball), and by Tolkien’s indication in one of the texts in Unfinished Tales that he used the stone only for its capacity for direct communication with other stones, for working on Saruman and Denethor. It’s an odd redundancy.

April 16, 2021 @ 1:34 pm

He was a Maia of Aule once after all, perhaps he just has a soft spot for tools and works of craft in themselves?

(And perhaps one can read into it a desire to surpass Morgoth but on a smaller scale; unlike his old boss Sauron can actually benefit from his stolen magic rock wrought by Feanor.)

April 16, 2021 @ 1:00 pm

There is one small exception in the movies regarding Sauron’s physical form. When Aragorn looks into the Orthanc Palantir (Extended Edition only), we get a brief glimpse of Sauron holding up his own Palantir, stolen from Minas Ithil. He appears exactly as he does in the prologue of FOTR, partly because he is exactly the same. It’s reused footage of him bearing aloft the Ring, with a Palantir superimposed and the image distorted by flame effects.

Of course, it’s still up to interpretation, since the Palantiri are notoriously unreliable at showing the whole truth. Pippin sees a vision of an (averted) future in which Minas Tirith’s White Tree is set ablaze. Denethor is plagued by visions of doubt. Aragorn glimpses Arwen, far off and fading. So the visage of Sauron seen in the orb may be filtered through Aragorn’s own image of Sauron in his mind, rather than a concrete reflection of his reality. In any case, it all fits with the interpretation of Sauron as an unseen figure, perpetually out of direct view.

I wonder how The Hobbit movies fit into this schema. Sauron’s role in them is adapted from tidbits of Tolkien’s later lore in LOTR and Unfinished Tales, and depicts Sauron as a vague dark figure, often wreathed with fire, which at times resembles his armoured form. Once again, it’s hard to tell whether he’s physical or not, acting more like an insubstantial cloud of malice.

April 17, 2021 @ 6:19 am

Fanart meanwhile often depicts Sauron as being a pale-skinned, white- haired pretty boy because of course it does.