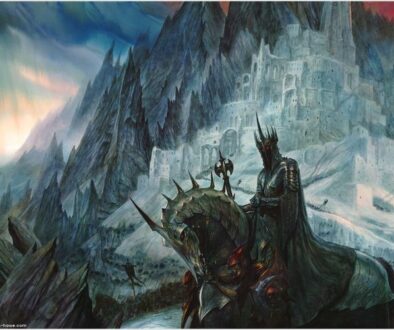

The Black Gate

Names: Morannon (Sindarin: “black gate”).

Location in Peter Jackson films: Tukino Skifield, Mount Ruapehu.

Description: An urban trough of Mordor. The place where traffic comes in and out as Sauron’s troops enforce Mordor’s stringent border security. This is the region where the mountain ranges of the Ephel Dúath and Ered Luithi meet. Mordor’s great intersection.

After treading across the Plateau of Gorgoroth and exploring its salient landmarks, we’ve reached a stage of our odyssey where we encounter a mix of landmarks and intersections. The northwest of Mordor incorporates a commerce region, or at least places where Tolkien’s idea of commerce takes place. Less defined by a single landmark than a mass of historical events, our approach to Mount Doom and Barad-dûr was functionally to write tour brochures on raggedy parchments that orcs might hand to visitors from Rohan or Erebor before their scheduled Hour of Torture with Sauron the Great. (They’d probably be confused by the bits about authorship and this fellow named Tolkien though). In this part of Mordor, we’re faced with a mass of places where seminal events happened long ago. The Black Gate is the crucial landmark of far northwestern Mordor, but to unlock it, we have to uncover the history of the lands around it first.

In its northwestern quarter, Mordor shares a border with Northern Ithilien, a fiefdom of its rival Gondor. As bordering neighbors at war, Gondor and Mordor wrestle for control over places on their borders — in The Two Towers, when Sam and Frodo arrive in the northwest, they meet Gondor’s Captain Faramir as he leads a campaign to expel the Haradrim, Mordor’s allies, from Ithilien. In The Return of the King, Gondor tries and fails to hold the abandoned city/military outpost Osgiliath, losing it to Mordor’s orcs. The region is one of the most tumultuous in Middle-earth, as the two most powerful forces on the continent vie to colonize it. Imagine the United States and Canada waging a war over Alaska, and you’ll get the picture.

Beyond the Isenmouthe (or Carach Angren) pass, our perambulation to the Black Gate starts in Udûn, a valley whose name literally means hell. It serves as an elbow to the arm of mountain ranges that encircles Mordor, Ered Lithui and Ephel Dúath. Tolkien wrote virtually nothing about Udûn, probably figuring that naming a place “Hell” was enough to mark it as notable. The only other information we have about Udûn is that it’s guarded by Durthang, a once Gondorian fortress appropriated by Mordor after Gondor abandoned its watch of the Black Land. It has little plot relevance to The Lord of the Rings unless you care about the brief divergence in The Return of the King where orcs Frodo and Sam fall in with before the destruction of the One Ring marched from Durthang, but it differs from Barad-dûr in a key respect. Barad-dûr was built by Sauron in its various incarnations. It was always Sauron’s construction, made of his own volition without outside cultural influence. Durthang is different: it’s Gondor’s construction, co-opted by Mordor. It speaks to a certain treatment of Gondor as a victim of Mondor’s malign influence: even the name dûr-thang is Sindarin for “dark oppression.” Earlier in this blog when we talked about how Tolkien defines evil by obviation, we framed it in terms of Middle-earth’s villains obviating their own souls. With Durthang, Tolkien’s fixation on obviation turns into a culture war that centers on the Big Bads from the East co-opting and eroding the culture and landmarks of the West.

And look, this isn’t just some political correctness-mongering from a power-hungry non-binary transgender socialist, although it is also that. The center of The Lord of the Rings is a malign Eastern power conniving to colonize and destroy the West through subtle influences. That Tolkien, a white man born in a British colony in the 1890s, held some unsavory Orientalist and white supremacist views should be uncontroversial. Tolkien was hardly subtle about the racist ideologies he subscribed to in his private life. In a now-infamous letter to writer Forrest J. Ackerman which decried a film treatment for The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien remarked on his displeasure with the portrayal of orcs:

Why does [screenwriter Morton Grady Zimmerman] put beaks and feathers on Orcs!? (Orcs is not a form of Auks.) The Orcs are definitely stated to be corruptions of the ‘human’ form seen in Elves and Men. They are (or were) squat, broad, flat-nosed, sallow-skinned, with wide mouths and slant eyes: in fact degraded and repulsive versions of the (to Europeans) least lovely Mongol-types.

The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, Letter 210

The furthest you can stretch a plausible defense of this description is that Tolkien applies his description to “versions” of Mongolian people. This is of course utter crap, as the preceding description is a comprehensive list of anti-Asian tropes seen in early 20th century literature and the Allies’ propaganda during WWII. Even if you want to distinguish between how Tolkien viewed his own work and how his books read today, you still have to contend with the smattering of instances in The Two Towers where the Uruk-hai refer to Rohirrim as “whiteskins,” and the anti-miscegenation subplot surrounding factions of orcs (we’ll get to that when we tackle Fangorn and Isengard). The orcs fill a narrative role as disposable mutants whom the heroes can slaughter without undue exercises of conscience. This treatment of Mordor and the orcs as corruptions of the West smacks of imperialist ideology.

A theological component of this arises as well. Tolkien’s belief in evil-beginning-in-good pervades his legendarium. He fears a world made entirely of surfaces, where an object’s accident is the whole of itself and its substance perishes. While nobody likes a narc and there’s nothing wrong with graffiti, Tolkien’s interests lie in straightforwardness and integrity (an ironic quality considering the often abstruse nature of his life’s work). In a personal memo written in response to W. H. Auden’s New York Times review of The Return of the King, Tolkien made some notes on his definition of evil:

In my story I do not deal in Absolute Evil. I do not think there is such a thing, since that is Zero. I do not think that at any rate any ‘rational being’ is wholly evil. Satan fell. In my myth Morgoth fell before Creation of the physical world. In my story Sauron represents as near an approach to the wholly evil will as is possible. He had gone the way of all tyrants: beginning well, at least on the level that while desiring to order all things according to his own wisdom he still at first considered the (economic) well-being of other inhabitants of the Earth. But he went further than human tyrants in pride and the lust for domination, being in origin an immortal (angelic) spirit. In The Lord of the Rings the conflict is not basically about ‘freedom’, though that is naturally involved. It is about God, and His sole right to divine honour.

The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, Letter 183

Tolkien’s fear of tradeable aesthetics and cultures reveals his reactionary paranoia. Cultural appropriation isn’t something the white, pseudo-European characters do; they nurture their own traditions and cultures, taking care not to mix traditions. (In this light, it’s not difficult to guess why Tolkien disliked C. S. Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia, an ultimate in literary bricolages). Tolkien’s politics take an isolationist bent here; exploring other cultures is iniquitous and corrupts people (he disdained both the United States and United Kingdom’s foreign policies of colonialism and total war). It’s no coincidence that Frodo’s quest centers on a shifty ring from the East. In short, Mordor is an imperialist nation, an empire made of Orientalist tropes and Western fears.

Mordor also possesses the most fearsome border security in Middle-earth. To the northwest of Udûn the pass of Cirith Gorgor, the place between Ered Lithui and Ephel Dúath, houses the intersection which oversees licit traffic into Mordor. Intriguingly for a conservative work, The Lord of the Rings positions Mordor as the lone majorly explored country with clearly delineated border security. Part of the security is geographic — as Mordor is encircled by forbidding mountain ranges, making one’s way in or out of it means passing through the Morannon, or “Black Gate,” the iron passageway to Mordor. Fledged by the Towers of the Teeth, the Black Gate is about as welcome as any border passage, which is to say it possesses equal hospitality to a front door that’s completely on fire. Take this description of Frodo, Sam, and Gollum’s encounter with the Black Gate:

Upon the west of Mordor marched the gloomy range of Ephel Dúath, the Mountain of Shadow, and upon the north the broken peaks and barren ridges of Ered Lithui, grey as ash. But as these ranges approached one another, being indeed but parts of one great wall about the mournful plans of Lithlad and of Gorgoroth, and the bitter inland sea of Núrnen amidmost, they swung out long arms northward; and between these arms was a deep defile. This was Cirith Gorgor, the Haunted Pass, the entrance to the land of the Enemy.

The Two Towers, Book IV, Chapter III, “The Black Gate Is Closed”

As the chapter title “The Black Gate Is Closed” indicates, Sauron’s iron gate is a labyrinth standing in the way of free travel, opening only for military allies of Mordor and the occasional ambassador from Gondor. Its nature as a gate is parodic, fulfilling a border passage’s job of providing Mordor with a sieve. A gate is nought but a more forbidding door, as Frodo and Sam learn when they see the Black Gate. The hobbits are forced to find illicit modes of travel, rapidly descending the social ladder while the rest of the Fellowship has a more teleological journey into the upper echelons of Middle-earth’s civil society. Aragorn is received with diplomacy and fanfare, while Frodo’s task puts him into orc custody.

At the Black Gate, Tolkien also provides a glimpse of how Mordor does diplomacy. When the Army of the West comes to the Gate in The Return of the King (or Gates, due to a typo by the screenwriters which was replicated by the production team), they’re greeted by Sauron’s ambassador, a man literally called the Mouth of Sauron. While The Silmarillion and earlier parts of The Lord of the Rings often stress the seductive beauty of Sauron, by the end of the Fellowship’s journey Sauron’s hand has been forced to coercive seeding of despair. Sauron himself, conspicuously absent from the action of the books, is represented by

…A tall and evil shape, mounted upon a black horse, if horse it was; […] The rider was robed in black, and black was his lofty helm; yet this was no Ringwraith but a living man. The Lieutenant of the Tower of Barad-dûr he was, and his name is remembered in no tale; for he himself had forgotten it, and he said; ‘I am the Mouth of Sauron.’ But it is told that he was a renegade, who came of the race of those that are named the Black Númenóreans; for they established their dwellings in Middle-earth during the years of Sauron’s domination, and they worshipped him, being enamoured of evil knowledge.”

The Return of the King, Book V, Chapter X, “The Black Gate Opens”

In this sequence, we learn the extent to which Mordor’s reliance on parodies of Men has fallen in might. Even the Nazgûl retain some vestiges of their past royalty, such as eldritch steeds and high office. Sauron’s ambassador is unnamed; “the Mouth” is a designation and a purpose rather than an identity. Sauron shows the Men of Gondor and Rohan a mirror of their appropriated selves. He provides a Satanic lure to despair, claiming Frodo’s death by showing off some of his possessions, relics of the once-great West:

“‘Dwarf-coat, elf-cloak, blade of the downfallen West, and spy from the little rat-land of the Shire—nay, do not start! We know it well—here are the marks of a conspiracy. Now, maybe he that bore these things was a creature that you would not grieve to lose, and maybe otherwise: one dear to you, perhaps? If so, take swift counsel and what little wit is left to you. For Sauron does not love spies, and what his fate shall be depends now on your choice.”’

At this point in the movie (a delightfully silly moment in the Extended Edition which is cut from the theatrical version), Viggo Mortensen’s Aragorn cavalierly commits a heroic war crime, whipping out his sword and lopping off the ambassador’s head with a characteristic Mortensen “yyyyaaaargh!” The book is subtler, with Gandalf expressing skepticism towards the Mouth’s claims. A mere vestigial relic of Númenor, the Mouth of Sauron speaks in even more archaic language than the cast of Men in this book — and The Return of the King gives its predecessors a run for its money in terms of archaic dialogue. At this moment the Fellowship rejects the dark mirror of their aesthetics, noting that garb without honor is a mere parody of their values.

While Tolkien projects a fixation with national identity and cultural purity onto the East, he stumbles on some fairly radical insights about the insularity of nation-states and the ugliness of borders. Borders are where countries enact violence on the populace of the world. Donald Trump may have left office a few months ago, but Joe Biden’s continuation of his predecessor’s border policy and internment camps for migrants can hardly be called reform. In his strident rejections of modernity, Tolkien hits on some legitimate humanist critiques of how nation-states are run and how national aesthetics are used to deceive and hurt people. As we pass through the Black Gate from the same side as the orcs and the Mouth of Sauron, we learn some key insights about the ugliness of Middle-earth and the real world that inspired it. On the other side, we may learn more about what happens outside the mendacious institutions of borders and gates.

April 30, 2021 @ 9:45 am

“Cultural appropriation isn’t something the white, pseudo-European characters do; they nurture their own traditions and cultures, taking care not to mix traditions.”

hmm. I see where you’re going there, but let’s note that mixing with Elves is almost always shown as good; i.e., Numenor inherits a lot of Elven ways, the Numenoreans are blessed as long as they keep close to the Elves, “fairy blood” is odd but basically good, and then of course the Common Tongue is “enriched and made beautiful” by the addition of words and grammar from Elvish speech, etc. etc.

As to borders: it’s clear that welcome — sometimes cautious or armed welcome, but welcome nonetheless — is absolutely central to Tolkein’s conception of Good. One does not simply walk into Mordor… nor into Mirkwood, nor the Lonely Mountain under Smaug. But one absolutely does walk into Rohan, Gondor, Rivendell, Lothlorien, and so forth. Armed Rohirrim or elvish warriors may soon show up to check your bona fides, but the border is absolutely open and you can stroll right in.

There are two fascinating intermediate cases that fit the pattern: Moria and Bree. At Moria, Gandalf remembers when the Gate was always open, and it’s still open to anyone who says “friend”. But now it’s both shut and guarded by a monster, because Moria has become a place of evil. And Bree has a gate that is shut; the gatekeeper is reasonable and lets them in, but this is a clear signal that Evil is afoot.

And then finally, at the end of the story, the first encounter the hobbits have with the corruption of the Shire by Saruman is that they encounter a closed gate at the Brandywine Bridge.

So: manned borders and closed gates are at best a warning of trouble to come, and quite possibly a sign that Evil is active.

Doug M.

May 1, 2021 @ 12:52 pm

To be fair, I talked about Tolkien’s implicit critique of borders in the post.

April 30, 2021 @ 8:15 pm

It’s that meditation on the corruption of power that I find most interesting here. What the wielders of the Elven Rings knew was that to use them actively was to fall. It always amuses me that people complain about Gandalf being a rubbish wizard because he never does anything; the one time he actually does show off his power, he, yes, falls…

[In a theological discussion, it’s akin to the perennial question about why, for an allegedly omnipotent being, God doesn’t seem to want to actually do anything. I think the answer is strongly related to this, myself.]

But yeah, it’s notable how the notion of borders and barriers has roared back into modern political discourse. Here in the UK, those of us who have been willing to embrace the idea that our home country might not be the centre of the universe have been dismissed as being “citizens of nowhere” (and, by extension, unpatriotic.) And, of course, it’s doubly ironic that it has happened at a time when a pandemic has reminded us that viruses do not respect borders.

May 1, 2021 @ 4:31 pm

I’ve nothing to add other than to say how much I’m enjoying this and the literal direction it is taking

May 2, 2021 @ 3:58 pm

Tolkien wasn’t the first writer to look at the Industrial Midlands of England, and the Industrial Working Class who lived there, and react in horror. H G Wells had already been there with his Morlocks. Tolkien, being a reactionary Little Englander, was at least consistent in his views whilst Wells was supposedly a socialist. You wonder though is his idea of a big, black gate to keep the urban proletariat out ofsight is something he thought was a good idea.

May 11, 2021 @ 10:21 am

“Tolkien’s politics take an isolationist bent here; exploring other cultures is iniquitous and corrupts people…”

Having trouble believing this of a man who knew over thirty languages (both ancient and modern) and who, to my knowledge, was never openly anti-semitic or racist but publicly opposed both.

From a letter to his son in 1945, Tolkien says:

“Yes, I think the orcs as real a creation as anything in ‘realistic’ fiction … only in real life they are on both sides, of course. For ‘romance’ has grown out of ‘allegory’, and its wars are still derived from the ‘inner war’ of allegory in which good is on one side and various modes of badness on the other. In real (exterior) life men are on both sides: which means a motley alliance of orcs, beasts, demons, plain naturally honest men, and angels.” – Letter #71

Given he was product of Victorian society, creating a fictional ‘lost’ Anglo-Saxon Mythology (he never forgave the Norman Invasion of 1066 for wiping them out of English culture), I think having Genghis Khan and his Horde as the default bogeyman in mind is understandable.

May 17, 2021 @ 5:05 am

… sure, the man who claimed that Europeans as a whole think the Mongolians include the “least lovely” people on Earth, and used anti-Asian stereotypes for his corrupted parodies of humanity, and who ascribed inherent cultural traits to Jewish people that he applied to the Dwarves wasn’t at all openly antisemitic or racist.

Yes, Tolkien said some good things too, and there’s a case to be made that when he actually thought about the implications of what he was saying he was able to overcome his baser instincts*, but much as I love the man’s work those instincts are still there, they make themselves known, and it doesn’t serve to deny their existence.

Certainly in terms of his languages he was quite happy for the tongues of Men at least to absorb vocabulary and grammar from the languages of people they encountered, because he actually knew how languages work.

May 17, 2021 @ 11:01 am

The man didn’t claim “Europeans as a whole think the Mongolians include the “least lovely” people on Earth”. For a start he puts a disclaimer, “(to Europeans,)” before “least lovely”, acknowledging Western cultural bias and highlights they were “degraded and repulsive versions” of “Mongol-types”, not actual “Mongol-types”.

The European cultural bias predates any recent ‘yellow peril’ anti-Asian trope. It’s roots are in the 13th Century Mongol invasion which reached Poland, Germay and Austria threatening to over-run the continent. Of course Tolkien would use it as an archetype in his (European) Mythology.

I’m unclear on the “inherent cultural traits” you claim Tolkien “applied to the Dwarves” which are “openly antisemitic or racist”. If you refer to the Dwarvish greed for gold and other riches, you need to take a closer look at Norse Mythology rather than Jewish stereotypes. Neil Gaiman’s book is a good read for that.

Tolkien had a spat with his German publishers in 1938 over having to supply a ‘Bestätigung’ (confirmation) he was Aryan before the Hobbit would be accepted for publication and he wrote;

“Thank you for your letter… I regret that I am not clear as to what you intend by arisch. I am not of Aryan extraction: that is Indo-Iranian; as far as I am aware noone [sic] of my ancestors spoke Hindustani, Persian, Gypsy, or any related dialects. But if I am to understand that you are enquiring whether I am of Jewish origin, I can only reply that I regret that I appear to have no ancestors of that gifted people.”

As for being racist, you do know he was born in South Africa and said in his 1959 retirement speech from the University of Oxford “I have the hatred of apartheid in my bones…”

Humphrey Carpenter’s book of Tolkien’s letters is also a good read (and a useful resource).

May 22, 2021 @ 6:11 am

Mm, not looking to defend Tolkien’s attitudes about Asian people, but I took that least-lovely thing to be “orcs resemble the ugliest Asian people,” not “Asian people are ugly and orcs look like ’em.” There’s lots of other nasty stereotypes there, but that particular line isn’t extra bad (unless you want to object to the idea that anyone is ugly, which… fair, but also definitely several steps woker than Tolkien ever was).

The Dwarven/Jewish thing is interesting to me. There’s a lot there, but it’s not especially straightforward. Sure, dwarves and stereotype-Jews both love gold, but even there the details of Tolkien’s dwarves cut against the stereotype: they mined that gold themselves, it is in no way the proceeds of commerce, let alone exploitation. In fact, they appear to be welcome and even beloved neighbors.* They both have “secret” languages, but of course Hebrew was never secret and I doubt if it would have occurred to Tolkien to think of it that way. I guess there’s a diasporan thing happening, but really in Middle-Earth who isn’t an exile? (Hobbits and Rohirrim, I guess, who have migrated but don’t seem to have a lost homeland as such?) The men of Gondor left their sunken homeland, the Noldor cast themselves out of Valinor, the Ents lost their collective ex-wives’ addresses.

In fact, I think the case for the Noldor (or possibly the Sindar) as fantasy-Jewish is rather stronger. Their origin myth fits better (the Dwarves are the product of a separate creation and can by no means be read as a monodeity’s chosen people, while the Noldor are definitely Big Chosen and the Sindar can be read as born into the chosen tribe, but where they remained in Middle-Earth instead of returning to Valinor, we could draw parallels to not buying that Jesus guy’s whole story), the manner of their exile fits better (the Grey Havens being a sort of literalized next-year-in-Jerusalem) and they have that whole secret-master-moving-the-pieces-on-the-chessboard thing that the Dwarves definitely don’t.

*Sure, the whole Smaug incident strained relations between Laketown and the Mountain, but they seem to have been allies for a long time before and after that. We are also told that Moria maintained mutally-beneficial trade relations with its neighbors. This just possibly might be intended as an oblique comment on Jewish communities, actually. Were it not for Tolkien’s stated dislike of that sort of allegory, I’d be tempted to read it as a lesson in how you’re lucky to be neighbors with the funny-sounding bearded guys. But in any case, it’s hard to cast it as anti-Semitic.

May 24, 2021 @ 12:52 pm

That’s an interesting interpretation of the Elves.

Re the Dwarves, there’s an ongoing change in their characteristics over the course of Tolkien’s writings, and the worst of it (at least according to this essay https://www.thefreelibrary.com/%22Dwarves+are+not+heroes%22%3A+antisemitism+and+the+Dwarves+in+J.R.R….-a0227196960 ) is confined to The Hobbit, at the midpoint from their evil depictions in the earliest form of the legendarium and their from-LotR-onward better depictions; like I suggested above, Tolkien had a tendency to improve himself if he bothered to think things through. (But, sadly, he still retained the belief that there was some kind of racial* martialness of Jewish people; positive stereotypes are still racist.)

As for the “least lovely” quote, I’d be inclined to go with your interpretation if Orcs resembled the ugliest corruptions of all humans; as it is, Tolkien did specify they look like the ugliest kind of Asian people only. Which was a choice, alas.

*or, perhaps more charitably, some kind of essential cultural trait attributed to people who just happen to all be part of a specific ethnicity

May 25, 2021 @ 11:28 am

This was a brilliant read. Thank you. Definitely waiting for more.

“The region is one of the most tumultuous in Middle-earth, as the two most powerful forces on the continent vie to colonize it. Imagine the United States and Canada waging a war over Alaska, and you’ll get the picture.”

It’s interesting to me that you used a fictional war over Alaska as an example here. In Central Europe, where I live, basically every single region has a long history of being constantly fought over and having ever-shifting borders. It’s so commonplace here that you forget there are places that aren’t like that. Everywhere’s a battleground, everywhere’s a graveyard. And when a place changes hands so many times, it often becomes impossible to tell who has the strongest claim to it, who it truly belongs to.

From this point of view, the struggle for Northern Ithilien is quite atypical: there’s no doubt that this place rightfully belongs to Gondor and that Mordor is just occupying it. For all of Mordor’s aggression towards the rest of Middle-Earth, its borders are virtually immovable.