Psychic Landscape 1: Conjuring the ’70s

This post is based on a true story.

This post is based on a true story.

The Conjuring movies are interesting for various reasons. There is, for instance, the way they use the 1970s themselves as a source of horror.

Actually, this sort of thing has been happening for a while now. As far back as The Sixth Sense, 70s clothing has been pulled into the mix. Moreover, Sixth Sense borrows heavily on the detached, clinical style of certain 70s and early-80s horror movies, such as The Exorcist and The Shining. You know the kind of shot I’m talking about. Steady or static shots of carefully framed tableaux, often in deep focus, usually with something irrational or horrific intruding matter-of-factly into an otherwise domestic, mundane, or banal – perhaps even aggressively banal – setting. The resurrection of this stylistic tick is in marked – probably conscious – contrast to other styles of horror filmmaking which were on the rise at the time, most particularly the ‘found footage’ style, the early phase of which was exemplified by The Blair Witch Project. Both styles were probably, in their different ways, reactions against the styles predominant in the late 80s, which tended to be very heavy on overt depictions of monsters, gore and/or body horror. These make-up-and-practical-effects-heavy films were also often very frenetic, witty, and self-aware. It’s no coincidence that the last gasp of such films (before they started getting re-made ‘on the square’) were boastfully self-aware, even pop-postmodern, films like Scream and Wes Craven’s New Nightmare.

There’s a definite sense in which films like The Conjuring movies are an attempt to reclaim or relive the feeling of ‘seriousness’ in horror films. Of course, the irony is that this very ‘seriousness’ is a function of the immaturity of the people who perceived it. I’m not calling them immature now; I’m saying it made its mark on them in the way it did when, and because, they were immature. The perception of seriousness comes from the intensity of unease which certain films inspire, and the unease is bound up with childhood. The attempt to use the mundane iconography of a bygone era – the 70s and early 80s – is the tell here. It harks back to an era when people my age – and James Wan, the director of the two Conjuring movies is a year younger than me – were encountering horror as kids.

I remember how anxiously fascinated I was by Tobe Hooper’s Salems’ Lot, Kubrick’s The Shining, The Wicker Man, Rosemary’s Baby, The Omen, The Exorcist, and other films (such as Peter Medak’s neglected masterpiece The Changeling) which, to the very young me, seemed deadly serious, transgressive, deeply unnerving, potentially traumatising, repellently alluring… and also inextricably bound up with flares and very wide lapels. I was, paradoxically, more able to get my hands on films like these than the films which were ‘current’ at the same time. In contrast to brand new films, which were in cinemas that wouldn’t let me in, or on VHS tapes I couldn’t afford and which my parents wouldn’t buy or rent for me, a lot of the previous generation of movies were on TV, recordable late at night. I can imagine, from my own experience of growing up, why filmmakers my age, currently making horror films, want to evoke the aesthetics of the 1970s, not only in aspects of style but also in tank tops. It feels right.

There is, of course, an element of nostalgia here, but all nostalgia is to some extent about wallowing in pain. It’s inherently masochistic. Nostalgia literally means ‘the pain of the past’ after all. Usually this refers to regret, or the inability to return to some longed-for arcadia. But we can also be nostalgic for pain itself, for anxiety or even terror that excited us or made us feel alive. This is surely all the more true of the pain of watching horror movies, which are after all crafted to be enjoyable. I had nightmares about Salems’ Lost, especially the scene where the little vampire boy floats outside his friends’ bedroom window, and the creaking of the rocking chair in which another vampire rocks. But they were exciting. I look back on those nightmares with fondness. You never forget your first nightmare brought on by a film, not if you’re made like me. Every time I sit down with a scary movie, I’m chasing that same original thrill of the first nightmare.

There’s also a potency for a child in seeing nightmares set in the immediate past, because for a child the immediate past is the time of origin, the near but inaccessible era of one’s arrival and early childhood, a fuzzy era of dim memories that seem at once both close and far away. To a 10 year old boy in 1986, a nightmare set in 1977 hooks directly into the part of the brain that was subconsciously recalls being a new entity at that same precise moment, an entity assailed by the utterly new and terrifying and traumatic and inexplicable. It’s the uncanny era you see in the photos in your parents albums. It looks so much like now but also like another epoch on another planet. To a small child, remember, Septembers last for years and your birthday comes round once a half-century. To a lot of people now, that preternatural ‘immediate past’ is fixed forever as that thing we call ‘The 70s’. This will be different for every generation. I’m talking about mine.

There are other reasons why the ‘70s-ness’ of the Conjuring movies ‘works’. One of the good moves the movies make is that they wholeheartedly and unabashedly embrace a Christianity-inflected demonological paranoia. In the world of these films, demons and spirits are everywhere. This is the thoughtworld of many who adhere to aggressively polytheistic forms of pseudo-Christianity in which a massive system of saints, angels and demons float around a universe heavily populated with spectral and semi-divine presences, in which signs and miracles are everywhere, in which prophecies are encoded within your morning toast. The forms of ‘Christianity’ that have asserted themselves as currently hegemonic in American culture are barely Christian by any coherent analysis of their actual theological content, and owe as much to a perverted form of 60s spiritualism (itself partly descended from 20s tent show revivalism) as they do to anything actually Christian. (The irony is that the present day Christian Right owes its existence at least partly to the great spiritual awakening of the 60s they hate so much.) Often highly demonological, polytheistic, even pantheistic, this pseudo-Christianity is essentially the ontology posited by the Conjuring movies. Even as the fictionalised heroes – very loosely based on ‘real life supernatural investigators’ Lorraine and Ed Warren – are presented as pious Catholics, they operate in a universe which is so seething with powerful spirits it is almost animistic. This is deeply 70s, and the aesthetics of the 70s, the 70s iconography in which the films are steeped, is a vital part of making them work, because our acceptance of ‘reality’ of what happens in the films is based upon our acceptance of the Warrens, their perceptions and interpretations, and acceptance of such is only really possible in the historical context in which it belongs.

The paranoia inherent in such an animistic and demonological pseudo-Christianity is also made acceptable by the 70s context, because the 70s has come down to us as the age of paranoia. Political paranoia has always had a link to the occult. It’s worth remembering that the first conspiracy theories were witch crazes (based on appropriating female property and degrading their social roles, enforcing the rise of capitalist patriarchy) and demonology. There is an occult side to all conspiratorial thinking (UFOs, secret cults, the Freemasons, the Jews and their imagined blood rituals, etc, etc). You see the occult thinking even in the apparently materialistic political paranoia fables. The nature of Washington DC is often brought up, both in terms of the occult nature of government and the rituals of power, but also in the actual layout of the city, designed as it was by odd educated men with hermetic class instincts and esoteric interests… something which has provided much fodder for kooks, especially Rightists.

You can often see the banal truth lurking beneath the surface of ghost stories that are ‘based on a true story’, and part of the banal truth of the ‘real’ cases the Conjuring movies are based on is the paranoia of the era… but I’ll probably come back to this another time, because it probably needs a post all to itself.

Parenthetically, ‘The 70s’ also has an extra tang of anxiety in retrospect now as it is a ‘place’ where we are inevitably going to feel stranded and helpless without mobile phones and the internet.

The other thing about the 1970s is, of course, that it is the era of the slow defeat of social democracy and the birth of neoliberalism. It is the origin of the world we currently live in. It is the period during which the counter revolution began, a counter revolution we’re only really becoming conscious of now that it has died in the Great Recession and then stood back up and carried on walking. But again, we’ll probably take that up another time. I have other fish to fry here today. Namely, the horror of the past.

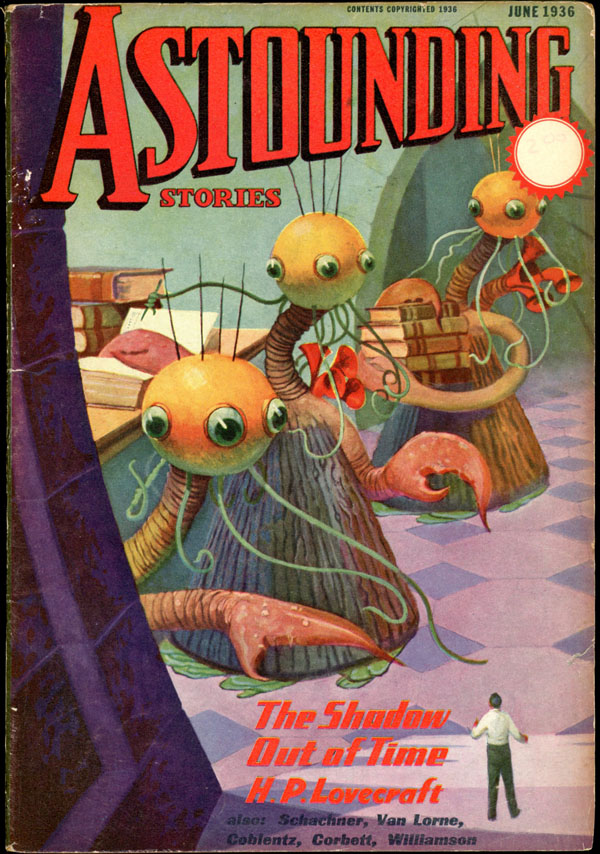

There is always something inherently terrifying about the past, or rather about the persistence of evidence of the past into the present. In a way, the entire gothic genre, the entire genre of the ghost story, is predicated on the innate horror of the past. But more than that, as Lovecraft realised when he wrote The Shadow Out of Time, material evidence of antiquity can in-itself be skin-crawlingly horrific, and this is all the more true when one sees evidence of oneself in that antiquity. Children can be acutely aware of themselves as new events, which means they can be acutely, morbidly curious about their origins, and about what the world was like before they existed. Solipsistic as they are, children have a greater capacity to comprehend that the world was there before them. This is bound up with death for a child. Because they are so close to their beginnings they can also be highly aware of their ends. Children – at least those children with the leisure so to do – tend to think and worry more about death, about nothingness, about extinction than adults. It’s not just because the concept of death is new to them, but also because being aware that they only recently appeared out of nothing, they are more able to imagine disappearing into nothing. Their origins are relatively recent, and so they are replete with evidence of those origins and the time before them. It’s almost like looking backwards at a reverse death. It’s a prophecy masquerading as a tale. The childhood fascination with one’s own advent is essentially morbid. The past itself is morbid. Also – it is intellectually close but, as per the child’s perception of time, it is also millennia ago.

Adults – especially young adults – spend a lot of time attempting to recapture the sublime vertigo of many such childhood sensations. They try to recapture something of this harrowing existential sublimity of time in fascination with archaeology, or history, or palaeontology, or human evolution, or astronomy and cosmology. There is a kinship between the cold, terrifying feeling of eternity and immensity that one gets from staring up at a star-filled sky and the feeling one gets from looking at fossils that are millions of years old. The Romantics knew why, though they tended to think more about mountains in Switzerland… but then they went on to write Frankenstein, so they knew what they were on.

This terrifying sublimity of time, and its kinship with the terrifying sublimities of space and childhood, is why Lovecraft’s The Shadow Out of Time is such a brilliant synthesis. It’s about… SPOILERS… a man whose consciousness is abducted out of his body and taken back in time to an alien civilisation that existed on Earth millions of years before humans even began evolving. The aliens are themselves planet-hopping time travellers who migrate via moving in and out of brains. The narrator has to piece together his own activities in the impossibly distant past by dream memories, until he uncovers archaeological evidence: his own written work preserved into the present within the ruins of the ancient civilisation. The story takes it for granted that time itself is horrific – and it’s right. The story works because it combines cosmic immensity with the horrific immensity of time, and binds it up with the idea of one’s own transportation through the terrifying wastes of passing millennia. And it is about the recovery of the memories of childhood, of one’s childhood self, of one’s own cryptic, half-remembered, incomprehensible presence within an era one barely and fuzzily recalls, with the pre-history of Earth essentially elided with the dissociative, haunted, blurry confusionscape of one’s earliest years.

The anxiety, and the generation of jumps and scares in films like The Conjuring, tends to be based on primal terrors of childhood. It’s no accident that both Conjuring movies, like so many movies of their kind, focus heavily on children within families. The fears of children, specifically of children in and of houses and homes, form the basis of the scare-systems in such films. There’s something under the bed. There’s someone in my room, standing behind the door. The eeriness of the depopulated and silent downstairs of the house in the middle of the night. The creaking footfall on the stairs. The darkness of the attic or basement. Surrounding these are the same persistent para-terrors. The deaths of pets, etc. But even more fundamentally, these films are based on the childhood feeling of helplessness, of smallness, of defencelessness, of being at the mercy of an incomprehensible world that is hostile to your intuitions and inclinations, of not knowing how to make sense of all the stuff happening around you, of not being listened to, of being treated as only partly human… in short, of the experience of childhood produces monsters. But the kinds of monsters being brought forth are different in different societies because the experiences are different. Also, there is no inherent reason why uncanny storytelling has to focus on the experience of childhood. But there is a tendency for it to do so in capitalist media culture, and to focus on specific aspects of childhood experience. Because the experience of childhood is deeply anxious in capitalist society, at least for most. And, in very foundational ways, it has to be, because of the private nature of the family in bourgeois society. Moreover, it’s meant to be, because childhood is meant to prepare children for a life of such unease and insecurity.

The private, atomised, nuclear family – a quintessential feature of developed industrial capitalist societies – is a breeding ground for terrors, not only for children themselves but also in their perception and vicarious experience of their parents’ adult lives. It is frightening because of its very privateness, its enclosedness, its separation from others. The walls of the family home are screens behind which one can enjoy privacy but behind which one can also prey upon the other people who are stuck behind them with you. Mainstream accounts of home and family-based horror stories will generally stress the effect of seeing a ‘place of safety’ violated by hostile and uncanny forces. A more poignant critique sees the hostile and uncanny forces not so much as a violation from without but rather an expression of something within.

This concentration of the haunted house variant of the horror genre upon domestic family life and childhood is another reason why the 70s themselves can be an icon of horror. Not only were the filmmakers who are now grown up and making movies kids in the 70s, and influenced by 70s films, but the 70s were an era when the American nuclear family became an intense focus of anxiety and paranoia, largely owing to the demographic changes, social changes stemming from the increased wealth of children, and the intensified way they are targeted by media, but perhaps most of all by the resistance of children and teenagers. Such resistance was relentlessly feared, demonized and pathologized. Annabelle, the prequel to The Conjuring, is set in the late 60s and features murders of respectable middle class parents by a returned wayward teenage daughter who has been inculcated into a Manson family-style cult. But it goes deeper than that. One aspect of some of the influential classics of 70s horror is the focus on the domestic. Rosemary’s Baby, The Omen, The Exorcist and The Shining are all, in one way or another, about children and nuclear families, about horror arising within the family itself, and with children as either victims, threats or vehicles.It went both ways. The horror of the upptiy kid is expressed (The Exorcist), but so is the subjection of the child to the savagely patriarchal and violent institution of the private nuclear family (The Shining). (Yes, I know that’s the 80s – but it’s only just.)

One reason why The Shining is so powerful for me is that there are moments watching it when I just think ‘that’s my childhood’. My young childhood in the late 70s and early 80s was spent in a household in which booze-fuelled domestic violence was a feature. But it’s more than that. It’s the overpowering feeling of being inextricably bound to, subject to, powerless within, an institution that does not present itself to you as something explicable, that doesn’t care if you understand it or agree with it, that subjects you entirely to forces outside your control, and which is preparing to fling you out into a world you don’t understand. Children are simultaneously terrified of being abandoned by their parents and intensely eager to escape them; they’re in the stressfully paradoxically position of wanting to escape those who protect them so that they can get out into a world that is like a yawning abyss beneath their little feet.

One reason why The Shining is so powerful for me is that there are moments watching it when I just think ‘that’s my childhood’. My young childhood in the late 70s and early 80s was spent in a household in which booze-fuelled domestic violence was a feature. But it’s more than that. It’s the overpowering feeling of being inextricably bound to, subject to, powerless within, an institution that does not present itself to you as something explicable, that doesn’t care if you understand it or agree with it, that subjects you entirely to forces outside your control, and which is preparing to fling you out into a world you don’t understand. Children are simultaneously terrified of being abandoned by their parents and intensely eager to escape them; they’re in the stressfully paradoxically position of wanting to escape those who protect them so that they can get out into a world that is like a yawning abyss beneath their little feet.

All parents are, essentially, tyrants. If you’re lucky, they’re benevolent tyrants. This is why so many fantasy stories for children are centred on orphans. The orphanhood of the hero or heroine is often presented by such texts as sad, yet it is also an integral and deeply satisfying aspect of the fantasy. It is the fantasy of autonomy, similar to the fantasy of autonomy that makes post-apocalyptic, last-man-alive stories so attractive. Autonomy is such a rare thing in hierarchical capitalist societies that there’s little wonder is it relentlessly fantasized about – be it by little children or the less-mature ranks of the Libertarians. The dream of autonomy is predicated on the eradication of those who prevent it. I’m not saying children want their parents dead (though they often do), anymore than I’m saying that we secretly want everyone else on the planet to die if we happen to enjoy I Am Legend. But the fantasy of being guiltlessly rid of the petty – if, hopefully, benevolent – autocrats who supervise and control every aspect of your life when you’re a child, who subject you to dictats you don’t and can’t understand, who refuse to explain anything to you, and to whose prosperity and security your own future is powerlessly chained, is, undoubtedly, a powerful and seductive one. It’s a fantasy you’re quite likely to continue to need as you get older, but perhaps never as acutely as when you first realise you need it.

Sinister is another recent horror film in the same vein as The Conjuring, and other films from the same general stable such as Insidious, in which the aesthetics of the past are employed to generate a sublime nostalgic horror. In Sinister it is the aesthetics primarily of the visual-technological recording of the past, and particularly the domestic recording of the past. Noticeably, it’s Super8 film rather than the handcams of the 80s and 90s. Home movie cameras and the silent, flickering film that results. In Sinister, the eerie family films – with titles like ‘Pool Party’ scrawled on the film cans – begin as secretive surveillance from the bushes and become records of the grotesque murders of entire families. It turns out… SPOILER… that in each case the murders are committed by one of the children of the family, under the orders of a demon who recruits child acolyte-slaves. There is an obvious element of fantasy wish-fulfilment here. And Sinister is not aimed at children, so where is the fantasy directed? It can only be aimed at the adults watching who remember what it felt like to be children, to be the children in the film, moved from home to home, from school to school (like the girls in The Conjuring, by the way) at the whim of an irresponsible and self-involved parent. The adults watching see the fantasy projected backwards into their – our – past, our childhoods, in the form of the Super 8 home movie footage, which is what childhood looks like to us.

The uncanny can do this. It can be more realistic than realism because it can express the fundamental, truthful, underlying twistedness of bourgeois rationality and bourgeois normality. And it’s worth remembering that this twistedness isn’t just visible in wars or imperialism or huge crimes perpetrated by governments and corporations. It goes all the way down. It is banal and mundane. It is quotidian. It is everyday life. In the privatised bourgeois nuclear family there is the property status tacit but inherent in the status of children in relation to parents, and of wives in relation to husbands. Then there is the way these husbands and wives and parents are like property or tools in relation to their employers and creditors – relations which children see and experience at second hand through their relationships with their parents outside of the workplace. The artificial and savage hierarchy of the workplace and of the state in relation to society, and the way this is mirrored in the artificial and savage hierarchies of school, which exists partly to prepare children for a lifetime of showing up on Monday morning, of domination by elites and submission to superiors, of dominating others in return, of engaging in competition and yet obeying authority, of being sorted into certain roles – including ‘success’ or ‘failure’ – which will guide where they end up in the adult anthill, slotting into the economy where capitalism needs them (contrary to the eternal claims of the system that it wants to nourish the potential of all). Children are subject to their own school-level version of much of the stratified anxiety of adult society under capitalism, but also experience their parents’ adult version on top of their own. Children are helplessly subject to the vicissitudes their parents face. Unemployment, bankruptcy, poverty, recession, debt; the idea that you could suddenly lose everything, become homeless, etc. If these things happen to the parents, they happen to the child – except that the child has even less control, even less say, even less comprehension than their buffeted and stormblown parents. Less dramatically, there is the constant awareness of being trapped in the same place with the same people and at their mercy, a the mercy of the nuclear family, privatised and atomised, forced into mutual self-reliance in tiny groups, forced into neurotic patterns of concealment and shame and domination. Then there is the patriarchal oppression of women and girls in the home, the influence of toxic masculinity upon the family dynamics. Mix this all up together in a very small pot, turn up the heat, and bring to the boil. All these things, taken as ‘normal’ make the world an uncanny and inexplicably terrifying place for millions of people, including millions of children. Then add the cognitive dissonance created by the way children are constantly reassured that life is fair, that virtue will conquer all, that happy endings are available for all who deserve them. The expression of this for many is constant, low-level terror. Sometimes the level of terror is drastic and recognised; sometimes it is so constant at a relatively quiet level that it becomes regular ‘background static’. But still, the real world, even the bit of it that’s supposed to be the place of refuge and safety, is a site of horror, paranoia, inexplicable threat, domination, humiliation, etc… and sometimes of overt (as well as structural and/or psychological) violence. Even those kids who do not directly suffer the worst know that they are at the mercy of the worst as a possibility. If this is inexplicable to the adults, it is even more so to the children. They don’t even understand what they don’t understand. If the categories of the uncanny and the horrific express deep faultlines in bourgeois society, the sinkholes and cracks in normality into which one can suddenly fall and be lost at any moment, without understanding what is happening to you, then those sinkholes and cracks look bigger and deeper and darker the smaller you are. And childhood may be the one time you can indulge your fascinated, terrified rage at all this, before you’re fully trained to take it for granted that you live in a modernity that is an incomprehensible minefield.

Paradoxically, the ghost stories that best express this are the ones that deny it and wholeheartedly embrace the supernatural at face value – because the supernatural is the full blooded psychological expression of the somatic and emotional experience of the inexplicable horror that is experienced. That’s why even quite cheesy films which embrace the supernatural are better expressions of the social anxiety that spawns them than more self-aware stuff like The Babadook, which knows it is about depression rather than about a monster, and takes pains to make sure you know it knows this.

June 23, 2016 @ 10:34 am

Great article Jack. Thank you. Lots to mull over. Is what you’re describing defined in some texts as Hauntology? I’m never quite sure what people mean by that term.

Being of a slightly older generation than you, my own childhood sense of the uncanny is bound up more in the pop imagery and bright optimism of the sixties and early seventies. Before the rot set in if you will. Perhaps this is why I find the Horror genre quite resistable and have always been more taken with the imagery of SF and Fantasy – UFOs, aliens (wierd but nice ones not the abducting ones) other worlds etc. Luckily as an adolescent I had Punk to knock some sense into me and save me from all that fey Hippyness. It’s interesting to me that your observations of ‘The Seventies’ stye as a horror signifier spotlight the more mainstream, middle class cultural signifiers, wide lapels etc. The 1970s Punk style has always resisted assimilation as a horror trope despite itself co-opting some of the transgressive imagery of an earlier era – The Damned and the Banshees comic-book/silent movie gothic horror visuals, the dubious use of Nazi symbols in the nascent punk look. I can only think of Spike in Buffy as a reasonably successful monstered (to borrow a phrase from Jane) punk rocker.

I wonder what imagery today’s millennial kids will dredge up from their turn of the century childhoods when they graduate from film school?

June 23, 2016 @ 12:39 pm

Hah, very interesting, Anton. I was noting as I read Jack’s post that I had had no interest in horror, and that my nostalgia was more towards the long 60s (being born in 1964), but hadn’t connected the two – until you brought up the same two points. Perhaps there is a link? Though how that would fit with Jack’s thesis, I’m not sure.

(Incidentally, I’m guessing you are a little older than me, given your reaction to punk? It had a strong impact higher up my secondary school c.’76-’77 but left my own cohort virtually untouched.)

June 23, 2016 @ 2:44 pm

I was one of the originals, Bowie casualty, Kings Road poser, 100 club, the,Roxy, the lot. But that’s another horror story. I was going to try and fit Doctor Who in my thesis somewhere but felt I’d gone on too much already. Something about post war sixties optimism in the Hartnell and Troughton eras giving way to the kind of existential horror Jack describes with the Pertwee/Baker years. With UNIT and the Romanas, K9s, Tegans, Nyssas and Adrics standing in for the Seventies dysfunctional family.

June 24, 2016 @ 3:25 am

It’s true horror movies never really monstered the punk rocker, though they were used to hilarious effect in Return of the Living Dead, but they were certainly monstered in American vigilante films of the early 80’s. In Death Wish 3 Charles Bronson guns down about 100 punks in the finale and in in Class Of 1984 some punks push a nice bearded liberal teacher so far that he has no choice but to massacre them during a school assembly.

June 24, 2016 @ 7:58 am

I believe that Hauntology has a proper literary-criticism definition but to me it has always meant something like you describe: that unsettling feeling one gets off a lot of old media, particularly that from the 1970s. And the 1970s were unsettling in retrospect: the fad for Brutalist architecture among state bodies; the “Population Bomb”; oil crises; stagflation; terrorism in Europe; the “Winter of Discontent”. I was born in 1973, though, so the era might have a particular resonance for me.

There’s the Scarfolk Council blog (http://scarfolk.blogspot.com) who do marvelous riffs on the graphic design of those times. And bands on the Ghost Box records label like The Advisory Circle (http://ghostbox.co.uk/) capture the slightly sinister electronic tones of all those public service announcements warning us not to play on frozen ponds.

I’d recommend Francis Wheen’s book, “Strange Days Indeed” as a factual account of just how screwed up the 1970s were. I mean, a lot of it went over my head, as I was so young but I remember stuff like the hunger strikers in Northern Ireland dying and people hanging black flags from their windows here in the Republic. Strange days indeed is right.

June 23, 2016 @ 11:19 am

The seventies must be on our minds. I’m working on a piece about Tarantino tomorrow. 🙂

The idea about what we find horrifying being connected to the material circumstances of our childhoods is definitely an interesting one, and I agree with much of your analysis. I’d extend by suggesting that what we consider “normal” is also deeply intertwined with our childhood circumstances; that push and pull between the normal and the horrifying in an individual’s life may explain a great deal of political psychodrama.

Just as a for instance, our parents (with the 40s and 50s as “recent past”) have spent their lives simultaneously seeking a return to the Good Old Days of picket fences/nuclear families while being outright terrified of Reds, noncomformists, and people of color being “uppity.” Likewise, I expect the millennial embrace of social democracy as a group has a lot to do with growing up under the destructive forces of neoliberalism. So it goes.

June 23, 2016 @ 1:07 pm

Really well-thought out piece, Jack. I find myself in agreement with everything you’re touching on here, and the films you’ve mentioned are the sort of horror films I grew up being scared by and enthralled with ever since.

“The Shining” is amazing. “Salems’ Lot” works despite being shackled by its TV mini-series pacing. It’s all in the little moments with that one. Other horror films from this general era that left the impressions on me you discuss here (outside of “Jaws” and some of the better slasher films) are the 1978 “Invasion of the Body Snatchers”; “Don’t Look Now”; “The Sentinel”; “Phantasm”; “The Beyond”; “Dead & Buried”; “The Brood”; “The Fog” and “Alien”.

As far as a modern horror film that reaches back for that late 1970s to early 1980s nostalgia, check out “We Are Still Here” (2015) if you have not yet done so. I enjoyed it better than “The Conjuring” (which I like).

June 23, 2016 @ 1:58 pm

Ah, the 1970s. Barf-green wall-to-wall carpeting and photos of the kids sitting on the lap of the creepiest Easter bunny anyone could find. Cigarettes and tiny cars that explode if you tap them just right. Giant collars, bushy mustaches, giant glasses, and stupid haircuts.

Leaded Gasoline when people actually had gas, cigarettes, Economic depression, one factory after another closing, muggings and murder, Los Angeles choked in smog, rampant sexual abuse of children.

I’m glad to have been born in the 1990s.

June 23, 2016 @ 3:03 pm

As someone born in 1990, I used to get terrible, awful nightmares about PCs – not of anything specifically that I’d seen on them, but of the sheer horror of what they were. Seemingly magic devices with the power to show anything and manipulate things, cleverer than me and often behaving strangely for unfathomable reasons. It embedded deep into my psyche, and if I’m on the computer too late at night and an error message pops up, I still get a hit of my old technophobia.

I wonder if it’s where my love of robots in fiction comes from. I also wonder if it might have a connection to the vaporwave aesthetic.

June 23, 2016 @ 11:25 pm

Yes yes yes. CD-roms played a massive role in the nightmares I had well into my teens, including a particularly terrifying one wherein Grover reached out of my computer screen and forced my hand through the monitor and told me that if I ejected the Sesame Street CD-rom I would spend the rest of my life without a hand. It’s kind of telling that the most popular webcomic of the past decade is more or less built around the question of “What if our universe was an irreparably scratched CD-rom?”

I think primitive CGI is going to play a huge part in the millennial horror aesthetic, judging by the videos of people like Andy Wilson and Bryko.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m_TXgsFsh8g

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lzoYfq_XRC8

June 24, 2016 @ 11:54 pm

I was born in ’89, and one of the scariest things in my childhood was in an Australian Soap Opera – either Home & Away or Neighbours. One of the characters was on drugs SCARY SOAP OPERA DRUGS and was being manipulated by some hacker – in effect, somebody using bad CGI on a computer screen. It was an older man’s actual face against computer graphics, with a slightly distorted voice telling the character to do bad shit, not trust anyone. That image of the monitor, slightly smudged in its bad special effects, stayed with me for about a year in 1998.

This is my new favourite of Jack’s writings.

June 24, 2016 @ 3:18 am

I was born in 83 so the horror movies I was watching on tv when I was little were the garish blood baths of the mid to late 80’s which is probably why I like series 22 so much and why I admire more than enjoy the sterile horror of the 70’s (with the exception of Don’t Look Now which I find to be one of the most exhilarating movies ever made). Also, I couldn’t finish the first Conjuring movie because it just seemed like such a poor copy of those films in exactly the same way Super 8 was such a poor copy of Spielberg. Don’t remind me of much better movies in the middle of your bad one.

Oh, and speaking of garish blood baths I want to give a shout out to Combat Rock which is the only piece of Doctor Who media that has ever and probably will ever include a reference to Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2.

June 25, 2016 @ 9:05 am

Good article. I’m another one who’s never been drawn to horror, but it’s a fascinating interpretation.

Not at all sure about this though: aggressively polytheistic forms of pseudo-Christianity in which a massive system of saints, angels and demons float around a universe heavily populated with spectral and semi-divine presences, in which signs and miracles are everywhere, in which prophecies are encoded within your morning toast

That sounds just like pretty much the entirety of pre-modern Christianity, or at least the parts of it that took place outside the context of technical theological debate – I mean, have you read much hagiography? Protestantism trimmed back some of it, particularly where the saints were concerned, but an awful lot remained, as illustrated by many of the excitements of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, notably the witch-craze. It’s only when Christianity starts to get intruded on by Enlightenment rationalism that you find a widespread version of the religion purged of its supernatural cast of thousands, and even then it was hardly universal at any time.

Now, it’s certainly possible to take the view that the beliefs and practices of the vast majority of a religion’s adherents through the vast majority of its history are “wrong” and “not the real thing”. There have always been plenty of people ready to do just that, but they do tend to be adherents of the religion in question themselves (even if Islam has in recent years picked up quite a few spectators eager to pontificate on what it “really” consists of from the outside, whether as a “religion of peace” or quite the opposite, with very limited reference to its history or its actual followers). And it seems, if I may make so bold, a particularly odd line for a Marxist to take – as a historical materialist, shouldn’t you be concerned with how an ideology has actually manifested itself in practice, rather than with an idealist conception of a “pure” version?

Indeed, if this sort of thing is “pseudo-Christianity”, I’m not sure on what basis you would define “the real thing”. You would presumably have to rule out the Gospels for starters, as “pseudo-Christian” texts full of signs, miracles, angels, demons and prophecies.

As an aside, this sort of thing is why I’m a little perplexed by the cliche of fantasy fiction in which Christianity or a surrogate for it is presented as “the non-magical one” (ASOIAF/GoT being a recent example). When comparing historical Christianity with other religions, it’s very hard to imagine anyone’s take-home impression being “it’s so free from pervasive supernaturalism!”.

June 26, 2016 @ 8:25 pm

Brexit has taken us back to 1971 and it’s looking pretty scary to me.