Pulp Frission

(Content Note: This piece contains descriptions of fictionalized violence against women of a possibly sexual nature and descriptions of bodily objectification through male gaze. It also contains some mention of foot fetishism and uses an extended metaphor around piss play. Consider yourself warned.)

(Content Note: This piece contains descriptions of fictionalized violence against women of a possibly sexual nature and descriptions of bodily objectification through male gaze. It also contains some mention of foot fetishism and uses an extended metaphor around piss play. Consider yourself warned.)

Quentin Tarantino’s Death Proof is generally considered to be the least impressive of his filmography, even by Tarantino himself. It’s a film obviously constructed around a car chase sequence and as the second half of a double bill whose lead-in is a mildly diverting action-horror-comedy; it’s none-too-surprising that few critics were all that kind upon release. I haven’t seen anyone on Eruditorum Press beat up on the Guardian lately, so let’s let Peter Bradshaw stand in for the critical consensus:

…Tarantino has had to pad this film with stuff that would hardly make the DVD’s “deleted scenes” section: long, long, long stretches of bizarrely inconsequential conversation between the babe avengers which are a big comedown from the glorious riffs from Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction. Tarantino appears himself in a wooden acting role (a real downer) and awards an unlovely cameo to his friend Eli Roth. But check out that head-on collision.

In defense of the commentariat of 2007, Tarantino has crafted a film that seems like just that kind of mindless fluff on the schedule of a week-by-week major-release movie reviewer. Few great films can be fully understood on a first viewing (unless you’re Pauline Kael I suppose). Then again (if I must take the opportunity to shit on the Guardian), the words “Zoe Bell” appear nowhere in Bradshaw’s review, meaning he entirely missed the greatest pleasures of even the surface level.

Nine years later, we need take no such excuse. Tarantino is a consummate filmmaker, hugely controversial, thoroughly aware of the controversy his films create, and in interviews manages to simultaneously talk incessantly and refuse to reveal anything of importance as to the intended meaning of his work. His persona and body of work are expressly designed to provoke a reaction, and even if Death Proof is the least of his films, it’s worth a second look. What are those interminable dialogue scenes doing, and why isn’t anyone talking about Royales with Cheese?

Looking again at the surface first, the conversations in this film are almost entirely among women. Young women to be precise, traditionally attractive party girls interested in booze, drugs, and hard cock. And in trying not to be judged, either by the other girls or by larger society, by how they like to enjoy that cock. And, over and over again, the omnipresent threat of aggressive men using their size, their social influence, their presence to dominate these young women sexually, to control female flesh for their own purposes.

Butterfly makes out with her nebbish boyfriend, clothes on, and makes him leave with a hard-on, and her friends laugh in disbelief, judging her for not just fucking him. Later, she’ll be pressured by social convention and by an aggressive masculine charmer in Stuntman Mike to perform a lap dance in the middle of a crowded bar. Shanna is afraid to bring boys to the lake house, not because of the boys themselves but due to her purity culture-obsessed father, who nonetheless makes the effort to drop in on his daughter and her bikini-clad friends “in case we might need anything.” Jungle Julia is stood up by her date, and is slut-shamed to Mike by her former classmate Pam, who claims Julia slept her way to the top of her field aside from making incredibly crude (and possibly transphobic) comments about Julia’s appearance.

And Pam. She’s arguably the one who has the most positive experience with Stuntman Mike, seemingly going along with his rough charm even though he’s “old enough to be my Dad,” and yet the first to die, screaming and begging for her life. It is she, and only she, who sits inside the Death Proof vehicle, seeing Mike as the hypothetical camera would see him, and it is with her that he exchanges the majority of his dialogue. In another movie, he takes her home, they exchange a decent fuck, and everyone goes on with their lives.

But slasher films, and this is structured explicitly as a slasher film, are not about sex and intimacy, but about violence and splatter. And about the threat of violence, which is why one of the most chilling and scenes in the film doesn’t involve any of our leads at all, but through Eli “unlovely cameo” Roth’s Dov, menacingly laying out his plan to shove sweet-tasting high-octane alcohol down the girl’s throats in order to get their dicks wet. This is a monster of a man, equally a sociopath as Roosh V, and the film shows him to us honestly and without remorse. But briefly; Dov isn’t the focus of the film but the texture of it. He and the attitudes he holds are the air these characters breathe. Oppressive patriarchy, toxic masculinity, and internalized misogyny pervade this film, explicitly, as soon as you start looking for it.

Stuntman Mike may be murdering young women, and far be it from me to defend a serial killer, but Texas Ranger Earl McGraw correctly susses him out, and decides to go follow the NASCAR circuit instead of bothering to pursue the case. You want a damning picture of rape culture, distilled through a hyperreal cinematic universe? There it is.

Originally, this was going to be my piece for today: a detailed and scene-by-scene examination of Death Proof’s conversations, examining the role of rape culture, purity culture, and the evils of toxic masculinity and internalized misogyny in each. But in rewatching the film (twice) this week for preparation, I started having to take the aesthetics of the film seriously.

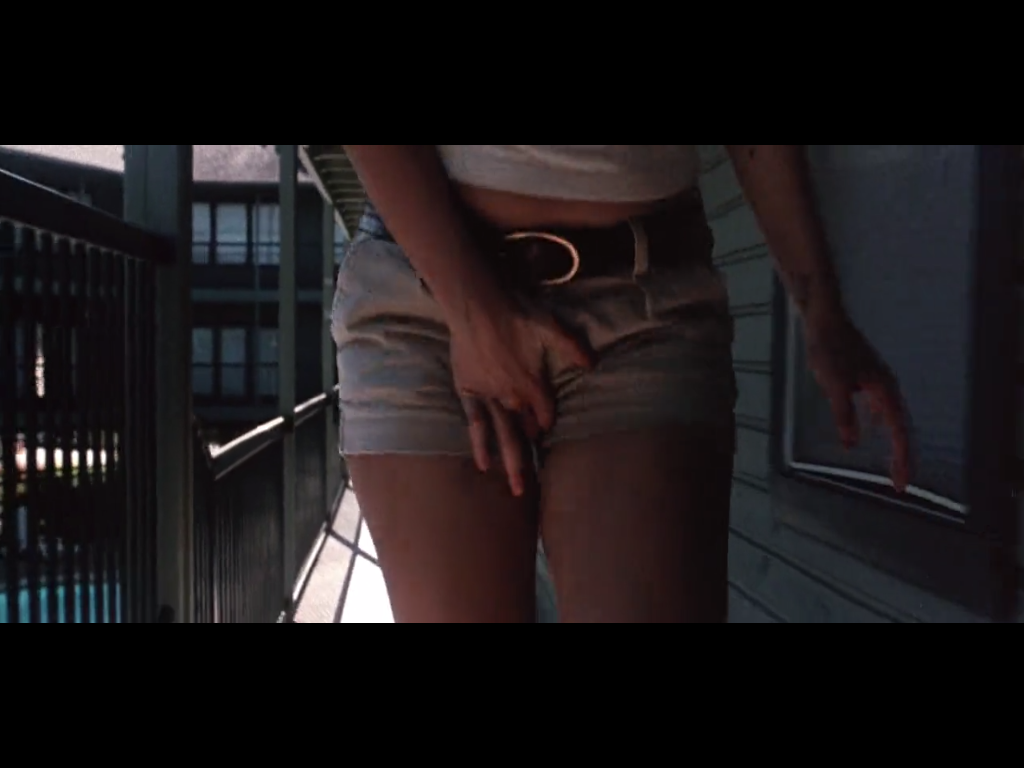

Tarantino is first and foremost and aestheticist and a stylist (although I believe he is also a sly revolutionary) who is often described as fetishistic, and his fetishes are so obviously laid bare in his films that it seems silly to even point them out. Yes, there are a ton of lovely female feet in this film, but we’ve known about this tic of Tarantino’s since at least Mia Wallace. (I have a running joke of claiming that Tarantino wasn’t actually paid for his work on From Dusk Til Dawn: sucking tequila off of Salma Hayek’s toes was sufficient return on his effort there.) Despite (or maybe because of) his interest in feet, Tarantino has more-or-less entirely avoided nudity in his films to date, unusual indeed for a filmmaker so heavily influenced by exploitation cinema of the seventies. And it is in this film, most explicitly about rape culture, that he includes his most loving shots of female anatomy, including Sydney Poitier bent over a window ledge and a Mary Elizabeth Winstead cheerleader (!!!) upskirt. And the extended lapdance sequence, not included in the original Grindhouse cut but fully restored for the DVD release.

What is Tarantino playing at? It’s tempting to go simplistic again, to argue that Tarantino is asking us to go along with the fun and games of the horror and slasher aesthetic, giving us a look at hyperstylized rape culture, and making us complicit through the camera lens in the dehumanization of the women in the film. I could be swayed to that, but I do think it’s more complex than that: the sexualization of the women is too explicit, the “rubbing our noses” too subtle. Funny Games this ain’t, and I’d think if Tarantino were interested in playing explicit metatextual games of that nature he’d give us a hint or twelve in dialogue.

No, I think the sexualization of the women in the film has a different purpose. Consider again that lapdance sequence: Butterfly takes off not a stitch of clothing, but makes the best of a bad situation to simultaneously raise (or at least maintain) her social status and attempt to get one over on Stuntman Mike at the time. Mike has teased her, pushed her around with his assertive masculinity (even going so far as to do a John Wayne impersonation), but in the moment where she can use her sexuality as a weapon against him, she performs an intimacy that Mike can only wish to have with her*, and she leaves him hanging. Or consider that aforementioned shot of Jungle Julia’s ass, an ass that becomes a point of contention a scene or two later when Butterfly is trying to get Julia to get to the point about the Frost poem already.

Sexualization, then, isn’t just something that the film is doing to the girls, but something the girls are doing to themselves. Sex is natural, fun, and warm — all seven major female characters in the film are explicitly pro-sex and fully enjoy the intimate company of partners. Lee-the-cheerleader even likes to be choked by a guy who looks like The Rock. Sex itself isn’t the enemy: aggressive, nonconsensual, violent sex is. The innocent cheerleader can enjoy a hand around her throat (egged on by her friend), Butterfly can give a lapdance (though socially coerced) for her own reasons, and Abernathy can sit in a pose that is butch as fuck on the edge of a muscle car while wearing cowboy boots.

Viewed this way, the film is not just taking advantage of pretty girls in skimpy clothes talking about dick, nor is it just punishing the viewer for enjoying the fruits of male gaze. It’s doing both, and exploring the frission of discomfort between the two. Think of Stuntman Mike’s turn to camera just after Pam gets into the death proof car, just before massacre that ends the first act.

He’s got a little smirk on his face, a isn’t this fun expression that comes across as incredibly disturbing on a realistic level given what he’s about to do. Given what we know he’s about to do, by the poster and the trailers and the fact that we’re in a slasher movie. We paid our money to see him kill these girls, so he’s smirking to let us know the fun times are a-comin’. Stuntman Mike becomes Kurt Russell, and Kurt Russell is giving us permission to enjoy the show. We’re all friends here; we’re all consenting to watch this, and as disturbing as the squares on the outside might find it, we’re going to have a good time.

Which reminds me. There’s a fetish I very explicitly didn’t mention in the piece so far, but it’s core to this reading of the film. Butterfly’s doing a pee-pee dance during the end of the opening credits, with the camera focused right up on her hand covering her crotch in a desperate attempt to not spill all over the place. Later, Lee-the-cheerleader tells us The Guy Who Looked Like The Rock is a great guy who “liks to watch me pee.” The other girls are accepting, laughing maybe at the silliness of it all, but certainly not disgusted or put off by Lee’s little secret.

Maybe I’ve been on the internet too long but I find a sort of delightful old-fashionedness in foot fetishism. It’s such a piece of the oddball mainstream that it doesn’t strike me as any more or less eccentric than Terry Zwigoff’s 78 collection or Sam Raimi’s brown suits. But piss play… that’s something you don’t see in mainstream films every day. By the standards of Middle America, it’s definitely way more “out there” than liking the looks of women’s feet. (None of this is to kink shame of course; I remain decidedly neutral on both feet and urine in my personal gratification.)

Kink and fetish are rarely really about the material realities of the activity, but are instead much more concerned with what’s going on between the ears of the participants or viewers. Headspace is king, and what an activity means is often much more important than what it is. All of which is to say if you don’t understand some particular sexual activity, it’s probably mostly because you’re not seeing it as the participants or enthusiasts see it. Watersports, as most who enjoy them will explain, is pleasurable because it is simultaneously very intimate and private (we often hide our bathroom activities even from those closest to us) while also being deeply taboo and dirty, on a physical and cultural level. I’ve seen piss play enthusiasts appreciate the tangy smell and taste of the stuff, and even enjoying the sticky residue it leaves when it dries, because it’s something done with a person or persons close to them that is incredibly intimate, yet also wholly rejected as disgusting/verboten by mainstream society.

If sex is an experience, and a conversation among people, then fetish is about finding those topics and points of agreement that set you outside the mainstream. Finding those dirty little things that you like with a partner, done behind closed doors and away from prying eyes, is an incredible bonding experience. As, for that matter, is sitting in a darkened theater watching a film that asks us to revel in the beauty of young women just before they are viciously destroyed. Tarantino is simply more honest than most slasher directors (who engage in simultaneous nudity and gore without examination of the effects of gaze), and by inviting us into the intimate circle with Russell’s break of the fourth wall and through the revelation of his own probable interest in piss play, he allows us to find our own place of frission between enjoying the spectacle and being discomfited by it. It’s an incredibly intricate balancing act, one which would find its fullest expression two years later in Inglorious Basterds.

(But that’s another essay.)

*Or perhaps with anyone. There is that moment (I believe also cut from the theatrical release) where Warren the bartender, after taking the drink orders, explicitly points at Mike and says, “Virgin.” I’d think this was reading too much into it except that Warren is played by Tarantino himself.

June 24, 2016 @ 1:49 pm

This is a strange movie for me because I hate it to pieces, on a purely immature aesthetic level (I don’t like slasher movies and I don’t like slow talky movies and this is a slow talky slasher movie), and have only managed to watch it once, yet some of my favorite Tarantino moments are right there in this movie. This movie I can’t stand and only saw once, I can still remember with perfect clarity Jungle Julia’s aforementioned ass (I’d have to be blind, asexual, and dead for 20 years not to remember dat ass), the foot on the dashboard, and Stuntman Mike’s fantastic “Which way you goin’, left or right?” speech. Any of them I’d rank up there with some of my favorite Tarantino moments, like the wedding massacre, or assigning the colorful names.

… those are all in the first half, aren’t they. Weird.

June 25, 2016 @ 4:00 am

Given the ending “cliffhanger”, it seems you might be talking about the metafictional aspects in the next essay, but I find it very interesting how the film uses the grain of old film stock, in particular how it disappears almost entirely in the second half.

Also intersting is how the film is kid of about the reclamation of a niche genre (car movies) by a group of female fans who want stories about the relationships between friends and lovers from a violent male one who wants stories about death and male loners and blood and guts. Just not his blood and guts.