Superhuman Effort to Keep Things The Way They Are (The Last War in Albion Part 7: Captain Clyde, Superheroes)

This is the second of five installments of Chapter Two of The Last War in Albion. The entirety of chapters one and two are available as an ebook single at Amazon, Amazon UK, and Smashwords. Please consider helping support this project by buying a copy.

PREVIOUSLY IN THE LAST WAR IN ALBION: In 1979, Grant Morrison began writing and drawing Captain Clyde for The Govan Press, a small local paper of a district in Glasgow. The comic attempted to depict a quasi-realistic local superhero, named after the River Clyde upon which Glasgow sits, who, like Morrison, was just an unemployed Glaswegian trying to get by. Installments of Captain Clyde are extremely difficult to locate, but several strips are publicly available…

“A society where nothing can change because it takes superhuman effort to keep things the way they are.” – Warren Ellis, 1999

|

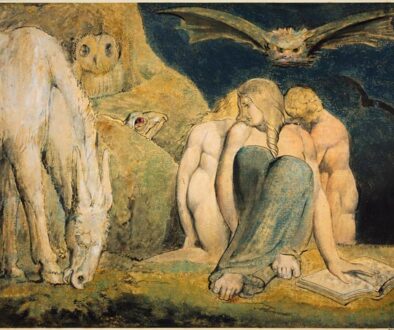

| Figure 48: The goddess Elen offers Chris Melville superpowers in an early installment of Captain Clyde (c. 1979) |

The first strip appears to be from the earliest days of the strip – a plot that O’Donnell describes summarises as Melville being “offered the powers of Earth and Fire by the earth goddess Elen – If he could defeat her champion, Magna.” This, Morrison explains in response, is because of “an interest in ley lines and earth magic and all that pseudo mystical, hippy shit,” marking the first documented instance of Morrison’s fascination with magic and the occult. Morrison reiterates this in Supergods, using the story of his uncle giving him the Aleister Crowley/Frieda Harris Thoth Tarot for his nineteenth birthday, which got him into magic as a bridge between his discussion of Chris Claremont’s run on the X-Men and his own Captain Clyde work. The anecdote culminates with him performing what he describes as “a traditional ritual” resulting in “a blazing, angelic lion

|

|

Figure 49: Lady Frieda Harris’s design

for The Magus (aka The Magician) in

Crowley’s Thoth Tarot

|

head… growling out the words “I am neither North nor South.” The second strip at least somewhat continues on that theme, showing Captain Clyde collapsed at the center of a stone circle before being renewed by some mystical power. This strip does not seem to immediately follow from the first, as Melville is identified by the caption box as Captain Clyde, suggesting it is not the origin story. Instead it appears to illustrate a feature of Captain Clyde, who, as Morrison puts it, “periodically has to recharge his powers by drawing earth energy from standing stones and other sacred sites.” The interest in Scotland’s otherness and pagan roots reinforces the initial sense of Captain Clyde as a sort of dissident superhero strip – an attempt to recreate the concept from the outsider perspective of an unemployed Glaswegian.

The other two strips are consecutive, and feature a battle between Captain Clyde and a villain named Quasar, who is described in Supergods as “a tweed-jacketed headmasterly villain” who turns into a “star-powered monster.” The chronology given in Supergods suggests this too is from the earlier portion of the strip, before its turn towards excess. This earlier portion is also presumably home to several of the smaller excerpts, which focus on the high concept “unemployed Glaswegian bloke as superhero” concept. These consist of Melville kvetching, both to himself and others, about the put-upon nature of his life. Other panels illustrate Morrison’s professed favorite of his villains, a character named Trinity who, as Morrison describes him, “was a schizophrenic with a triple personality who was able to divide his body into

|

|

Figure 50: The unemployed Chris Melville complains

about his hard knock life

|

three – each with a different power and facet of the personality.” Another illustrates the Sinister Circle, which O’Donnell admits he considers Captain Clyde’s “finest hour.”

The remaining illustrations seem to be from the later period of Captain Clyde, which Morrison described in 1985 as “very grim and unpleasant” and “full of nasty deaths and evil forces” due to his having completely given up on any belief that anyone was actually reading his comic. In Supergods he describes the final arc as involving Captain Clyde being the victim of “full-scale demonic possession,” becoming the “self-proclaimed ‘Black Messiah,” and finally being “redeemed by Alison’s unswerving devotion” and killing the Devil itself before dying in a “rain-soaked, lightning-wracked epic of Fall and Redemption.” This is probably at least somewhat tongue in cheek, given Morrison’s 1985 admission that the story “was compressed into eleven episodes from the thirty or so I’d originally planned.” These strips are more

|

|

Figure 51: The terrifying visage of the

Black Messiah

|

poorly represented in the Fusion interview. The panels in which Melville succumbs to his Black Messiah persona are represented, but the precise details of a sequence in which a villain named Belphegor summons a fire elemental named Surtr are more obscure, as is a sequence in which a character prophetically talks about “a taste of dread on the wind… as though the end of all things draws near.” The tone suggests the demon-inflected later years of Captain Clyde, but even this is speculative.

And that’s about what can be discerned about Captain Clyde. It is in many ways the most important of the poorly documented incidents in the war. Morrison, for his part, is open in boasting about the strip due, one suspects, largely to the fact that it allows him to claim victory in a priority dispute with Alan Moore. Morrison cheekily presents Moore’s seminal work on Marvelman as “the next stage beyond the kitchen sink naturalism of Captain Clyde,” a claim that couples with his frequent suggestion that Moore’s Marvelman work inspired him to get back into comics. Morrison also, in late 80s/early 90s interviews, cites Captain Clyde as a sort of trial run for his major contribution to 2000 A.D., Zenith, a strip Morrison also presents explicitly as a reaction to Alan Moore.

|

| Figure 52: The naval base in Faslane |

This illustrates a key and in many ways inscrutable feature of the War, which is that a vast amount of it takes place around a topic that can only be described as idiosyncratic: the superhero. The superhero was not in and of itself big in the UK – certainly not in the same way that, for instance, 2000 AD or Eagle were. American superhero comics, on the other hand, were for a crucial period quite popular, albeit for idiosyncratic reasons. The usual story, which is perhaps more folklore than sound economic analysis, is that copies of American superhero comics in excess of what sold in America were repurposed as ballast for trans-Atlantic shipping. Once they were in the UK they were typically sold off as an afterthought, entering the markets through idiosyncratic distribution at cut-rate prices. (Interestingly, Morrison has suggested that the nearby American submarine bases in Faslane and Holy Loch meant that American comics were particularly likely to be available in Glasgow, claiming that the Yankee Book Store in Paisley was the first store in the UK to stock them.)

That’s in print, at least. On television, as the commissioning of Captain Clyde demonstrates, the Adam West-fronted Batman television series was a perennial bit of televisual ballast. So while the idea of the superhero was well known, it was firmly an imported concept. The only British superhero

|

|

Figure 53: Mick Angelo’s Marvelman,

essentially the lone significant British

superhero

|

of any significant note was Mick Angelo’s Marvelman, who, by 1979, had not been published in sixteen years, and even he was just a cheat to work around the consequences of the National Comics Publications v. Fawcett Publications debacle. Superheroes were an American thing that some British children enjoyed alongside the existing selection of British comics.

Among these British children, however, were both Grant Morrison and Alan Moore, a detail upon which the entire War hinges. This cannot be stated unequivocally enough – without both of their loves for American superhero comics, none of this would ever have happened. In this regard, being asked to write Captain Clyde was a huge deal for Morrison, who had been designing superheroes since his teens. But it is also worth stressing the degree to which its genre further places Captain Clyde outside any mainstream conception of the British comics industry of its time.

Still, it is worth discussing the superhero, both for its later influence upon the War and to provide a broader context for Morrison’s early work. The superhero is generally considered to have been invented by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster in 1938 for Action Comics #1, which was headlined with the first appearance of Superman. On one level this is unequivocally true and the only sensible understanding of the origin of superheroes. Certainly this is the origin story Grant Morrison used in Supergods, his at times compelling and at times maddening history of the superhero, which he opens with the

|

|

Figure 54: Cover of Action Comics #1,

usually considered the first superhero comic

|

text of the Superman Code. And it makes sense – Superman was the first of DC Comics’s wave of superheroes, followed quickly by Batman, Wonder Woman, and the first versions of the Flash, Green Lantern, and other heroes. The basic paradigm copied tentatively by one of their rivals, Timely Comics, which quickly churned out the Sub-Mariner (by Bill Everett, who is often claimed to have descended from William Blake, a misleading claim given that Blake had no children, although he is a distant relative), the Human Torch, and Captain America.

Superhero comics were popular in World War II, then declined, with Timely (by then Atlas Comics) cancelling all of its superheroes, and DC whittling its roster down to Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman – still treated as the nominal Holy Trinity of DC’s superhero line. But in the 1950s a team of DC editors and writers including Julius Schwartz, Gardner Fox, Carmine Infantino, Robert Kanigher, and John Broome created Barry Allen, a new version of World War II-era superhero the Flash, kicking off the Silver Age of American superhero comics. Atlas, once again followed suit, but this time hit on massive success with what is now the Marvel Universe, featuring the Fantastic Four, the X-Men, Iron Man, Thor, Spider-Man, and a revamped Captain America. The history of superheroes from there to the present day is relatively easy to infer the broad strokes of, and relevant details can be left for later.

|

| Figure 55: Doc Savage, a prototype of Siegel and Shuster’s idea of the superhero |

Upon closer inspection, however, the release of Action Comics #1 is not quite the sui generis debut of the superhero that it might appear. Superman clearly fits into a tradition of masked crimefighters like Zorro, the Green Hornet, and the Shadow, who are themselves subsets of a larger category of pulp heroes including Doc Savage, John Carter, and Conan the Barbarian. Superman is original inasmuch as he’s both costumed and superpowered. But it’s impossible to create a definition out of these two facts. Costumes alone fail to distinguish the post-Superman characters from the pre-Superman ones. But equally, Powers are not a requirement of the post-Superman ones, nor absent from the pre-Superman ones. The second step in the standard history of superheroes, Batman, has no powers and is essentially indistinguishable from the Green Hornet or the Shadow, save for the fact that he happened to debut after Superman. And while nothing on quite the scale of Superman’s powers existed, there’s not a sizable difference between Superman’s powers and Doc Savage’s training since birth to be the absolute theoretical peak of human ability. Yes, Superman is an alien, but the situation is visibly just the reverse of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s John Carter, who has vast physical abilities when transported to Mars because his body is better adapted to the planet. Jerry Siegel even admits to the inspiration, and his powers were far less impressive in the early days than they are now. Even absolutely demanding the fantastic origin of the powers doesn’t work – the Shadow, when transported to radio, had what were blatantly supernatural powers.

|

| Figure 56: Many consider the costume to be a fundamental aspect of Superman |

So neither costumes nor powers are original to Siegel and Shuster. Nor is the idea of combining them adequate to explain the invention of superheroes. Costumes are not sufficient to define superheroes, and powers are not necessary. Whatever the idea of the superhero is, it resists a straightforward definition that links it inextricably to Superman. It is, however, telling that superheroes are inexorably associated with one particular medium: comic books. This separates them from almost any other popular genre, and suggests a more useful way of isolating them from adjacent genres. Superheroes have a visual dimension. This is also not an absolute rule – Batman and Superman both had radio shows, and novels like Robert Mayer’s Superfolks clearly featured superheroes despite not being illustrated.

For the purposes of understanding the War, however, an absolute rule that can be used to separate superheroes from non-superheroes is less useful than an explanation of why the terrian is how it is. Clearly the publication of Action Comics #1 was a landmark event in the development of superheroes. It defines the terrain upon which much of the War is fought. What matters is not what the terrain looks like, nor even what precise creative decisions caused it to look that way, but rather a larger question: why is this terrain worth fighting over? The answer to that question, at least, can be understood straightforwardly through the visual.

|

| Figure 57: Joe Shuster’s frenetic art style put the “action” in Action Comics (Action Comics #1, 1938) |

What Action Comics #1 indisputably was is the first massively successful attempt at the pulp hero to be defined by colorful visual representation. Technologically speaking, this was not popular until cheap four-colour printing was possible. Accordingly, it was in 1930s comic books that it happened. The cleverness of Superman was that he used color well. He was bright – even lurid, and Siegel and Shuster had what was, for the time, a shockingly kinetic style of visual storytelling. What was crucial was not the idea of a costumed hero with special powers, but the fact that this particular costumed hero was interesting because he looked good. Grant Morrison tacitly confirms as much in Supergods, spending pages analyzing the visual composition of the cover of Action Comics #1, writing in ecstatic tones of “the vivid yellow background with a jagged corona of red” in its background and linking its visual design to “the gateway of the loa (or spirit) Legba, another manifestation of the ‘god’ known variously as Mercury, Thoth, Ganesh, Odin, or Ogma,” the latter being, predictably, a figure from the Cath Maighe Tuireadh, a ninth century celtic text.

The superhero is thus best used to describe a type of pulp hero story that emerged out of 1930s American comic books. Not all superheroes have their origins in comic books, but enough do that it is a reasonably entertaining game to identify ones who first appeared in another medium, particularly ones that have any degree of popularity today. They are defined primarily by a visual intensity and a sense of heritage tracing back to Action Comics #1. And they are worth fighting over because pulp heroes of that sort are a large part of contemporary culture, and have come to almost completely dominate the American comic book industry, in which large swaths of the War are fought.

But the War starts in Britain and remains, in the end, fought in Albion. And in British comics culture superheroes never gained the absolute dominance over the comics industry that they did in America. [continued]

August 29, 2013 @ 12:26 am

"The only British superhero of any significant note was Mick Angelo’s Marvelman, who, by 1979, had not been published in sixteen years"

What about Captain Britain? He began in 1976, no?

August 29, 2013 @ 1:45 am

Yep, the first original character to be created by Marvel UK. Although since Captain Britain Weekly folded after less than a year, it's arguable whether he was "of any significant note" in 1979.

August 29, 2013 @ 2:45 am

It's Mick Anglo not Angelo. That aside it's interesting to note that both Marvelman and Captain Britain in their original conception, were merely cookie cutter versions of existing American superheroes. The former eventually causing a copyright tangle that continues to this day and feeds into the War in Albion such that I've no doubt you'll be addressing it. There were no ( and it might be argued never have been any) indigenous British 'four color' superheroes without a USA prototype, inspiration or publishing patron. The UK comic strip characters who delivered a similar but subtly different dose of 'thrill-power' might be The Eagle's Dan Dare in the 1950s, In 'TV Comic' our own Doctor Who, plus in 'TV Century 21' Thunderbirds, Stingray (and arguably the Daleks), though these were all TV inspired, in the 1960s, '2000AD's Judge Dredd in the 1970's and of course V for Vendetta et al in the 1980s. The point of difference to note, and I'm certain either Phil or other of you learned company will expand on this, is how the British 'heroes' reflect different aspects of imperialism, colonialism and the UK's self image, Dan Dare for example as basically the Royal Air Force in space. What it seems Morrison and Moore are attempting with Captain Clyde, V and Marvel/Miracleman is a reclamation of a particular British cultural archetype through mysticism and a pop culture version of ancient Celtic myth. A similar trick will be attempted in 2000AD with Slaine and over at DC with Camelot 3000.

August 29, 2013 @ 3:15 am

Dundee based publisher DC Thompson did several superheroes in The Hotspur over the years.

The Black Sapper – he had The Worm, a very sophisticated burrowing machine that he used to defeat various villains who always made the mistake of having their secret lair underground. Large holes in the wall and large explosions were inevitable.

Nick Jolly – 17th century highwayman unaccountably transported through time with his faithful nag Black Bess, who was herself transformed into a twin-jet propelled flying horse. Fantastic art by Ron Smith and delightful tongue in cheek scripts. Let's face it, they'd have to be. Debuted circa 1974. Black Sapper mid 50s.

King Kobra – debuted, mmm, 76ish. Cobra based costume with an inflatable hood whichallowed him to balloon down from high buildings in the same way cobras don't. Thankfully. Fought crime in The City. Ron Smith on art again.

The Spider – Fleetway published this in the 60s and its most notable because the early scripts were by Jerry Siegel at his nuttiest.Reprinted a few years back.

Axa – ah, what redblooded lad in the 70s didn't notice Axa. Ran in The Sun newspaper, Axa wandered the untamed post apocalyptic wastelands dressed in a fur bikini with s big sword. Sometimes, well, once a week on average, she'd dispense with the bikini. Corrr…

Modesty Blaise even ? She and Willie had an uncanny mental bond that Peter O'Donnell often hinted at bordering on telepathic.

August 29, 2013 @ 3:34 am

Well I was hoping someone would provide examples to dispute my claim although some are reaching a bit, Axa? barbarian of dubious heritage, Modesty Blaise? Spy-Fi, Nick Jolly? Time displaced adventurer. The Spider and King Kobra hmmm. Okay maybe but arguably American superhero inspired, The Black Sapper? just bizzare, a burrowing machine? Not sure that counts as a superhero trope. Anyone else?

August 29, 2013 @ 5:54 am

The iconic British comic book heroes (defining "iconic" roughly as "ones that immediately spring to mind without mental effort") are Dan Dare, Judge Dredd and Modesty Blaise. It's interesting that none of these has done well in live-acton adaptation.

If we go to broader pop culture, of course then we bring in Doctor Who, James Bond, Steed and Mrs Peel, Robin Hood, King Arthur and Merlin, Sherlock Holmes and possibly Harry Potter if the next generation of kids keep reading his stories. None of these are even attempts to emulate costumed superheroes of the classic American variety.

It seems that in Britain, while we enjoy the American superheroes, we don't emulate them when it comes to creating our own popular culture.

It's interesting to contrast this with popular music, where the American influence on Britain is very strong. Of course, the influence there goes both ways, but all the distinctively British pop music from the Beatles to Black Sabbath, Pink Floyd to Ian Dury, Tricky to Dizzee Rascal has clear roots in American blues, jazz and hip-hop. This kind of cross-fertilisation just doesn't seem to have happened to any great extent when it comes to heroic adventure stories.

August 29, 2013 @ 6:55 am

Aren't there very few significant US superheroes, let alone UK, to be created since the first years of Marvel? There's Wolverine of course.

August 29, 2013 @ 7:52 am

This comment has been removed by the author.

August 29, 2013 @ 7:53 am

This is off-topic, but I have to say I was enjoying my Tumblr feed this morning on the bus, when I almost choked at the sight of the photo you posted, Phil. LOL!

August 29, 2013 @ 7:54 am

Part 6 was – I think – about Scottishness and Englishness, and how the pagan Celtic roots of Scotland manifested themselves for Morrison's comics.

‘Instead it appears to illustrate a feature of Captain Clyde, who, as Morrison puts it, “periodically has to recharge his powers by drawing earth energy from standing stones and other sacred sites.” The interest in Scotland’s otherness and pagan roots reinforces the initial sense of Captain Clyde as a sort of dissident superhero strip’ – the Scottishness of it is its "outsider-ness"?

August 29, 2013 @ 7:56 am

Sláine IS those Celtic myths though, really.

August 29, 2013 @ 7:56 am

And how could we forget Bananaman?

On the subject, does anyone else remember Leopardman? He was in Buster (checks Wikipedia to confirm) as a serious older child strip among the comic strips. He was a schoolboy living with his aunt who was bitten by a radioactive leopard; his most important power was pretending not to be Spiderman. My faint memories are that the story was better than that sounds.

August 29, 2013 @ 7:59 am

One part of it, certainly. The "superhero on the dole" aspect is another, as is, I think, Morrison's own sense of protest at the directive to write an Adam West-style superhero, and his response by making the strip progressively darker and more unappealing to its potential readership. (The snide comment I don't really make is that far from presaging Marvelman, Captain Clyde presages the collapse of Marvelman's intelligence and potential into the Image-style overwrought darkness of the early 90s)

August 29, 2013 @ 9:06 am

While I haven't read many of the earliest stories, I believe the early Captain Britain stories were produced by Marvel US and just printed in the UK. I think it's only with Hulk Comic (which started in 1979) that there were UK produced Captain Britain stories, and even then he was a supporting character to the Black Knight. It would be September of 1981 before Captain Britain got his own starting feature that was actually produced in the UK, in Marvel Super-Heroes 377. Of course, with the last page of the story in 386 less than a year later the series enters the War in a big way.

August 29, 2013 @ 10:24 am

On the contrary, that recent Dredd movie with Karl Urban was fantastic, though it admittedly goes for a grittier look than the flashier, more comic book-y Stallone version.

August 29, 2013 @ 10:54 am

I'm afraid I'm not really clear on what you mean by distinguishing between "producing" and "printing" (without any mention of "publishing", which I would consider the relevent point).

Certainly Captain Britain Weekly was published by Marvel UK, and the title feature wasn't a reprint of American material, like the other stories they were publishing at the time. To the best of my knowledge, Cap never appeared in American comics until after Weekly collapsed, when Claremont wrote him into Marvel Team-Up.

Whether Marvel US had some sort of technical assistance in actually preparing the book for publication, I have no idea, but if they did, I don't think such assistance makes the book itself any less "British".

August 29, 2013 @ 10:56 am

I do not know how anything could be better than that sounds.

August 29, 2013 @ 10:59 am

My main objection would be that Claremont is more accurately considered American than british. Sure he was born in the UK, hence him getting the Captain Britain gig, but he was an American-based writer who lived in the US from the age of three. And Herb Trimpe was straight-up American. So I would consider Captain Britain Weekly to be an American comic produced for the British market.

August 29, 2013 @ 11:00 am

It occurs to me that the problem is "superhero tropes" are "USA prototypes and inspirations". Trying to find a UK character that is definitely a superhero, but isn't copying American superheroes is like trying to find an example of "Western manga" that isn't copying what the Japanese are doing.

(Having said that, might comedy characters like Bananaman and Super Gran count? Or is the former basically Captain Marvel with a healthy snack instead of a magic word, and the latter too far from the archetype?)

August 29, 2013 @ 11:02 am

Of your three choices, two of them are very much part of larger organisations (Dare and Dredd). While Dredd obviously is the law on his own, it is only because of the larger organisation of Judges. This is very different from the American super-heroes that were all independent operators. Even in the one really successful golden-age team book, All-Star Comics, the heroes only came together at the end of the story after individual solo or duo chapters. The American myth of the Individual is very much at play at the heart of super-hero comics. Comics like the JLA and the Avengers are exciting because all of these individual operatives come together to team up. The X-Men still fits into this, because even though they are a team first and foremost, they are outsiders, outside of the government so to speak.

Of course there are exceptions, but this might be an interesting point of comparison between British and American comics, the America mythic Individual and the comics of the post-war welfare state (or dreams of Empire) leading to characters being part of something larger than themselves (for better or worse, particularly in Moore's work).

August 29, 2013 @ 11:19 am

In DC & Marvel there's certainly been a drop off since the 70s, can't think of anyone significant since Rob Liefield's Cable (1990) & Deadpool (1991) in terms of Marvel, whilst at DC Harley Quin, (1992/3)a Villain who first appeared in Batman: The Animated Series is the only signifcant character from the past 20 years to have gained much traction. There have been new superheroes, but they're generally 'legacy' characters such as the various Robins, Green Lanterns, Young Avengers or B & C list mutants that get subsumed into the never-ending second act that is superhero comics – witness DC & Marvel's inability to do much with Kirby's 70s creations (Apart from Morrison's Seven Soldiers/Final Crisis work).

The main reason for this I think is lack of creator ownership/profitability – Don't forget Len Wein gets nothing from the Wolverine films. Also the sucess of Road To Perdition (Based on a graphic novel originally published by a DC imprint)for Dreamworks & 20th Century Fox lead to Warner Brothers changing the creater-owned contracts at DC/Vertigo to give them a better slice of the pie/first refusal on different media versions of the properties. This resulted in a lot of creators moving their own stuff elsewhere, especially Image – This change in the contracts also contributed in AMC's decision to make The Walking Dead, as they were originally looking at Brian Wood's DMZ.

With Moore's famous run-ins with DC regarding the issue of ownership it is surely going to be a factor in the War moving forward, not to mention the Jarndyce v Jarndyce quagmire that is (Marvel/Miracle)Man.

August 29, 2013 @ 11:27 am

Doing Captain Marvel in the style of a Dandy/Beano strip has to be unique to the UK.

August 29, 2013 @ 11:33 am

I've got a vague recollection of Billy the Cat and Katie appearing in some Beano 70s annuals, given the lack of superpowers hasn't hindered Batman from becoming one of the most recognisable superheros in the world (assuming you count been mega-rich a superpower) I'd say they qualify as superheroes.

August 29, 2013 @ 1:36 pm

As I understand it, everything short of the actual printing stage was done in the US on the original Captain Britain stories- from commissioning to writing to drawing to editing. Marvel UK did have a very small staff, which made further changes to make the books suitable for the UK. (For what it's worth, the London editor for Marvel UK at the time Captain Britain started was Neil Tennant, later of the Pet Shop Boys and the source of David McDonald's stage name.)

I think it's not inaccurate to say Captain Britain was an US comic published in Britain in its original run. If you want to say the Black Knight feature with Captain Britain that started in 1979 was a UK comic, I would agree. But that would have been simultaneous with the start of Captain Clyde.

I've heard Claremont was chosen for Captain Britain specifically because he was born in Britain, for what little that's worth.

August 29, 2013 @ 4:17 pm

I would be so delighted if Bananaman came into the War.

August 29, 2013 @ 8:17 pm

P. Sandifer wrote: 'The usual story, which is perhaps more folklore than sound economic analysis, is that copies of American superhero comics in excess of what sold in America were repurposed as ballast for trans-Atlantic shipping. Once they were in the UK they were typically sold off as an afterthought, entering the markets through idiosyncratic distribution at cut-rate prices.'

I was there and I think this is the truth.

That is, as a kid in London in the 1960s, I used to have to hunt around for American SF paperbacks, mags, and comics. These would emerge in outlets scattered around the city on such an arbitrary basis – often months and years after they'd come out in the US — that I methodically tried to figure out what my best bets were if I wanted to get that next issue of Fred Pohl's IF or GALAXY or whatever.

Hence, I asked the people who sold me the stuff. Nobody ever gave me any other explanation than that the stuff was being shipped over as transatlantic ballast.

August 29, 2013 @ 9:39 pm

a misleading claim given that Blake had no children, although he is a distant relative

Does he count as a collateral descendant?

August 29, 2013 @ 9:52 pm

First I've heard of Super Gran. But I created a Super Granny comic when I was 8. Can I sue, can I sue?

August 29, 2013 @ 10:00 pm

I think this tendency in the UK to turn superheroes into comedy characters is indicative of a larger attitude amongst publishers (and TV writers) which possibly affects how the British public views the trope as,a whole. I'm not sure where it has its roots but I suspect it to be something to do with British comics being seen as anthologies of 'humour for kids' rather than the American model of 'continuing stories of adventure for kids and young adults'. This goes some way to explaining the popularity of the camp comedy Batman TV show over here and the reason Morrison's publishing editor expected Captain Clyde to be a comedy strip.

August 29, 2013 @ 10:01 pm

"I do not know how anything could be better than that sounds." I hear this in Julian Glover's voice.

August 29, 2013 @ 11:35 pm

Actually, the first costumed comic hero was the Phantom, first published in 1936 and pre-dating both Superman and Batman. He was the first to have the classic superhero skin-tight costume and eyeless mask, which Lee Falk based on Robin Hood's tights and Greek statues. The Phantom doesn't have any superpowers though, and his stories are much closer to the masked crimefighter and pulp hero traditions.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Phantom

August 30, 2013 @ 1:25 am

"First I've heard of Super Gran."

The deprived childhoods you must have on your benighted shores.

I don't think Supergran quite counts as a superhero in that a) she started out life in books, had a tv adaptation, but has never to my knowledge had a comic strip; and b) doesn't have a recognisable as such costume. As a character she works basically like Sarah Jane in the Sarah Jane Adventures.

August 30, 2013 @ 1:46 am

"As I understand it, everything short of the actual printing stage was done in the US on the original Captain Britain stories- from commissioning to writing to drawing to editing."

Ah that makes sense, got it. Just in terms of 'British superheroes' he was the first one that jumped to mind, but I was thinking of the character, not the conception. Fair enough!

August 30, 2013 @ 2:49 am

There was a Super Gran graphic novel; the Picture Puffin book Super Gran In Orbit. And I'm not sure comics are a requirement anyway; the characters in Superfolks (referenced by Phil) are definitely superheroes, as are the Champions in Soon I Will Be Invinvible.

I take your point about the lack of a costume, though.

August 30, 2013 @ 2:54 am

Okay, I take Eric's point about most of the production being done in the US; esentially it was a reprint mag that happened not to have an original publication it was reprinting from.

Not sure I agree with Phil that the nationality or residency of the creators is relevant, though. Is Morrison and Frank Quitely's New X-Men a British comic for the American market? I'd say it's just an American comic created by Brits.

August 30, 2013 @ 1:02 pm

Interesting point.

The only notable exception I can think of (the FF don't count because they're not an organisation, they're a family) is the Green Lantern Corps. I mean, you could argue that Hal Jordan is a mythic individual because he is The Greatest Green Lantern and therfore his mythic power is greater than that of the Corps (the Captain Kirk effect), but you could say the same thing about Dredd.

August 30, 2013 @ 1:24 pm

Yeah, it doesn't fit perfectly, but it is something to notice.

August 31, 2013 @ 2:10 pm

I was thinking about The Leopard of Lime Street (as I believe the strip to have actually been called) myself. Not that I remember much beyond the basic premise, but YANA, David.

January 18, 2014 @ 7:56 pm

I did think of the Phantom as well as he predates Superman, but although he's popular here in Australia, and in parts of Europe and Asia. He's never reached the heights of Superman, and I think Philips point that colour was the defining trait which created the Superhero movement is spot on, and may even account for the Phantom's lesser status as the strips are to this day in black and white. By the by there is another contender who predates the Phantom. The Japanese Skull faced Character called the Golden Bat or Phantoma.