Hyrule Haeresis 1

“’Suppose that truth is a woman-And why not? Aren’t there reasons for suspecting that all philosophers, to the extent that they have been dogmatists, have not really understood women?’ There is thus a residue that philosophy has not known how to read, for which it has not been able to account. When matters become urgent or when truth is at stake, Nietzsche gives this residue a name: woman.”

–Beyond Good and Evil, Friedrich Nietzsche, as translated by Judith Norman, as cited by Avital Ronell in conversation with Anne Dufourmantelle in Fighting Theory

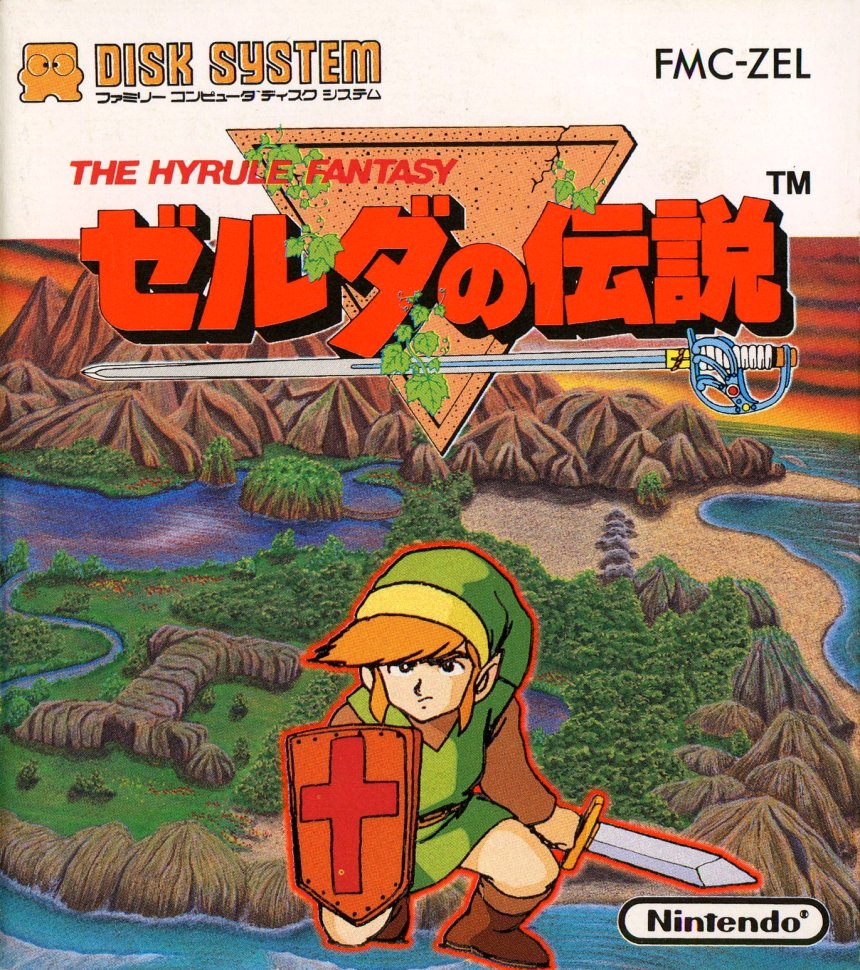

Zelda no Densetsu (lit. The Legend of Zelda) opens up with the declaration that this is a legend that has been “passed down from generation to generation”.

The Legend of Zelda has thus been, from the very beginning, something from the recesses of our shared memory. The secret history of Zelda is that she truthfully only exists at her purest in an unknowable primordial state lost long ago to the collective dreamtime. Even the “original” Legend of Zelda arrived in its present state shaped by the expectations and experiences of its previous incarnations. It is also, first and foremost, a fairy tale in the most classical sense: It is a coming of age story about a boy becoming a hero and, through doing so, finding his true self.

Not only is The Legend of Zelda a fairy tale, it’s a very specific and particular fairy tale, namely, Super Mario Bros. Designers Shigeru Miyamoto and Takashi Tezuka were working on Zelda no Densetsu for the Famicom Disk System at the exact same time they were working on Super Mario Bros. for the Famicom (though Super Mario Bros. was to be released first in 1985, a year ahead of Zelda in 1986), and the two titles wound up sharing a great deal of thematic concepts and overtones. One of which is the plot: In both games, a peaceful fantasy kingdom is invaded by an evil wizard from another land. The only person powerful enough to stop the wizard is the kingdom’s princess regent, who is captured and locked away so she can’t fight back. A humble, unassuming everyman steps forth and volunteers to go on a journey to free the princess, repel the invaders and bring peace back to the land.

The first way in which The Legend of Zelda is transformed from its dream-state thus comes about as consequence of being filtered through the lens of Super Mario Bros. And there are certain things irrevocably lost and altered in translation: Most notably, Super Mario Bros., as we have since learned from games like Super Mario Bros. 3 and recent statements from Mr. Miyamoto, is fundamentally a travelling stage show reinterpreted as a video game. There is no constructed “Mario Universe” and the Mario characters are merely a troupe of actors. The basic story of Super Mario Bros. is reiterated in every “serious” mainline Mario game because it is nothing more than a stage show being performed in different venues at different times with different interpretations from the company.…