Hyrule Haeresis 1

“’Suppose that truth is a woman-And why not? Aren’t there reasons for suspecting that all philosophers, to the extent that they have been dogmatists, have not really understood women?’ There is thus a residue that philosophy has not known how to read, for which it has not been able to account. When matters become urgent or when truth is at stake, Nietzsche gives this residue a name: woman.”

–Beyond Good and Evil, Friedrich Nietzsche, as translated by Judith Norman, as cited by Avital Ronell in conversation with Anne Dufourmantelle in Fighting Theory

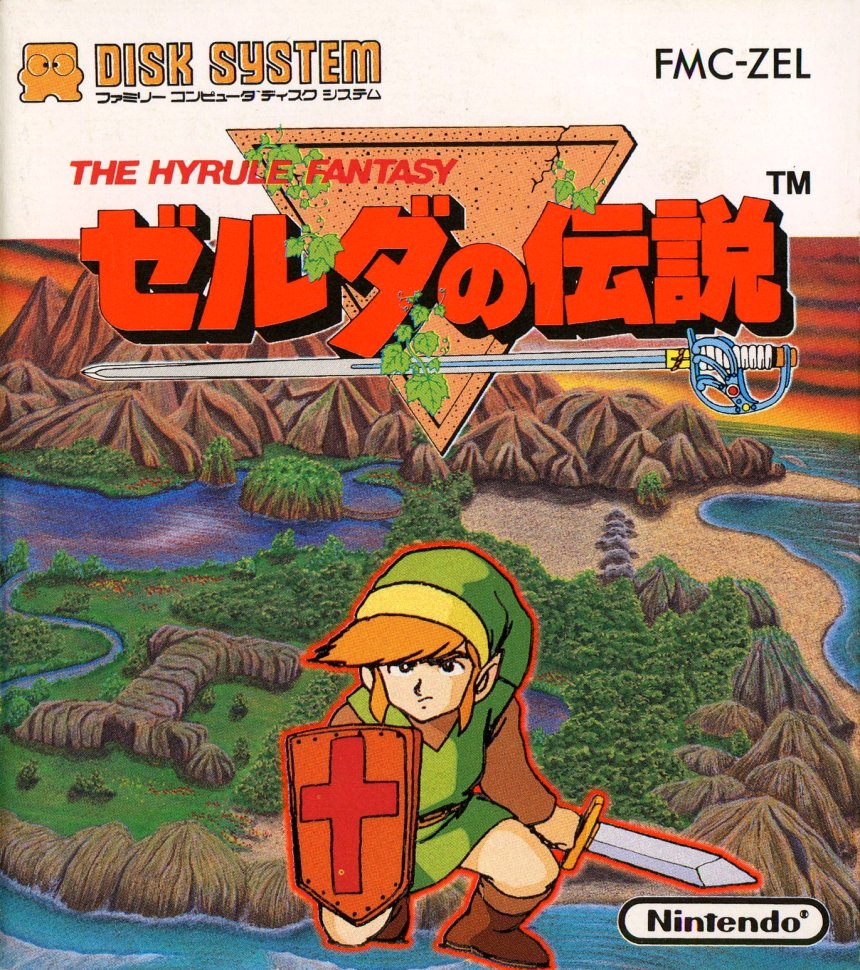

Zelda no Densetsu (lit. The Legend of Zelda) opens up with the declaration that this is a legend that has been “passed down from generation to generation”.

The Legend of Zelda has thus been, from the very beginning, something from the recesses of our shared memory. The secret history of Zelda is that she truthfully only exists at her purest in an unknowable primordial state lost long ago to the collective dreamtime. Even the “original” Legend of Zelda arrived in its present state shaped by the expectations and experiences of its previous incarnations. It is also, first and foremost, a fairy tale in the most classical sense: It is a coming of age story about a boy becoming a hero and, through doing so, finding his true self.

Not only is The Legend of Zelda a fairy tale, it’s a very specific and particular fairy tale, namely, Super Mario Bros. Designers Shigeru Miyamoto and Takashi Tezuka were working on Zelda no Densetsu for the Famicom Disk System at the exact same time they were working on Super Mario Bros. for the Famicom (though Super Mario Bros. was to be released first in 1985, a year ahead of Zelda in 1986), and the two titles wound up sharing a great deal of thematic concepts and overtones. One of which is the plot: In both games, a peaceful fantasy kingdom is invaded by an evil wizard from another land. The only person powerful enough to stop the wizard is the kingdom’s princess regent, who is captured and locked away so she can’t fight back. A humble, unassuming everyman steps forth and volunteers to go on a journey to free the princess, repel the invaders and bring peace back to the land.

The first way in which The Legend of Zelda is transformed from its dream-state thus comes about as consequence of being filtered through the lens of Super Mario Bros. And there are certain things irrevocably lost and altered in translation: Most notably, Super Mario Bros., as we have since learned from games like Super Mario Bros. 3 and recent statements from Mr. Miyamoto, is fundamentally a travelling stage show reinterpreted as a video game. There is no constructed “Mario Universe” and the Mario characters are merely a troupe of actors. The basic story of Super Mario Bros. is reiterated in every “serious” mainline Mario game because it is nothing more than a stage show being performed in different venues at different times with different interpretations from the company.

The Legend of Zelda lacks this level of diegetic performativity. At a cursory glance, the world of Zelda no Densetsu seems to be asking the player to take it at face value, whereas by contrast the bolted-on sets and frequent curtain calls of Super Mario Bros. 2: Doki Doki Panic and Super Mario Bros. 3 make the nature of its world fairly obvious. This becomes quite clear even in the original Super Mario Bros. once you consider that its marquee star is Mario, a character created specifically to be if not a mascot, at least a reoccurring character throughout Nintendo’s library, and who had made numerous appearances both major and minor even prior to his 1985 star turn. Zelda’s “Link”, however, was deliberately intended to be a blank cipher whose only personality and characterization would be what the player themselves projected onto him, hence his given name: The “Link” between the player and the game.

In other words you’re meant to step into Mario’s shoes as a working actor. You’re meant to transform yourself into Link.

This poses something of a problem for Zelda in regards to its rather stock plot. While not quite as rote and sexist as their detractors like to claim, both Super Mario Bros. and Zelda no Densetsu are both admittedly standard stories that aren’t perhaps quite as progressive as we might prefer either. This is because, quite simply, they are fairy tales, and fairy tales by definition have to be at least somewhat reactionary. But Super Mario Bros. is built to take this in stride by virtue of its performativity: We can excuse the stock setup because we understand this is an in-universe play we’re participating in the production of, so there’s a level of distance between us and the exact politics of the show the characters are putting on. This story will not work as well transposed into a different context that lacks this crucial component,

And yet Zelda no Densetsu hedges against this as well. Not a play, Zelda is instead exactly what it says it is: A legend told and retold that is passed down from generation to generation until it falls to us. It doesn’t belong to our world or our history, but to that of mythology and imagination. And critically, its nature as a video game means Zelda becomes something no story like it has ever been able to be before: Like all oral tradition it’s a set of beliefs and practices, but it’s also the ritual engagement with those practices itself. Through the visceral, sensory experience of playing the game we are undergoing our own ritual spiritual journey of exploration, yet at the same time we are also being guided through it by the game’s own mechanics and design, and thus those of the designers-Our elders.

It is not, I think, a great stretch to interpret video games as a modern form of ritualized shamanic practice. Arguments have already been made by others that all myth, perhaps all art, exists to remind us of metaphysical truth and that the “imaginal realm” is a reality that underpins all of human experience. But it’s video games that have the potential to convey this the most directly and viscerally through their unique emphasis, and dependence, on active, real-time human motor agency. Even just on a superficial level, most video games follow some basic formula of travelling through mystical Otherworlds gaining knowledge and spiritual power in order to become stronger and better. And it’s Nintendo’s repositioning of the status of video games in culture that drives this into focus: Ironically enough, its by bringing in a presumed audience of children that makes the makes the connection to the metaphysical all the stronger.

(This is not to say of course that oral tradition cannot be engaged with: That is, in fact, the entire point of it. Merely that a video game can contain both the description of the ritual and its praxis all in the same package.)

Of Shigeru Miyamoto and Takashi Tezuka’s two magnum opuses, it’s Zelda no Densetsu that’s poised to make this point the clearest, because Zelda no Densetsu is also a coming of age story by design. Super Mario Bros. isn’t because both Mario and Luigi are professional, adult working plumbers who are supposed to be at least middle-aged by the time the events of the story begin. Princess Peach is likewise intended to be a fully grown ruler (and a powerful sorceress, in fact) who presides over her kingdom. Link, however, is explicitly called a “young lad”, and while she’s never outright stated not to be an adult, Princess Zelda is likewise implied to be younger, perhaps around Link’s own age. She does have a nursemaid, and her official art makes her appear to be rather childlike.

(In fact, this Princess Zelda seemingly bears a striking resemblance to Princess Clarisse from Lupin the Third: The Castle of Cagliostro.)

This takes Zelda no Densetsu away from the more general fantasy of Super Mario Bros. and into the realm of explicitly children’s fantasy literature, but more importantly it also evokes the very ancient tradition of the rite of passage. Link goes on a mystical quest to defeat Ganon and rescue Princess Zelda, thus becoming initiated into both adulthood and the ranks of warrior shaman.

But there’s a problem. By invoking the rite of passage and making it foundational, The Legend of Zelda also invokes some very patriarchal and exclusionary cultural norms and beliefs, and makes them intrinsic to its being in the process. Rites of passage traditionally mark a transition from boyhood into manhood, and are thus exclusively male. Some traditions even liken female states of being and female existence to be a nascent null state that boys must transition out of to become men by shunning and rejecting anything considered feminine during the rite of passage.

And this is what Zelda no Densetsu does: Supposedly a “Legend of Zelda”, the old joke has always been that the title character always plays an ancillary, supporting and ephemeral role in a story about Link’s journey. And, in spite, or sadly rather because, of his conception as a player cipher, Link is from the very beginning forever destined to be coded as explicitly and firmly male. Ironically enough, this is a fate Super Mario Bros. manages to *avert* by making its protagonists mascots, because cartoon character mascots are effectively asexual. Mario was envisioned as a working everyman character anybody could relate to, and thus his appeal is limitless. Link, however, is hamstrung by the limitations of the traditions he chooses to invoke.

Anyone can be Mario. Only boys can be Link.

So what of Zelda, the woman who is seemingly omnipresent and yet also invisible and intangible? Her story is destined to be the heretical one. The apocryphal one. She is the secret history of this Legend, a shadow in every sense. Zelda is at once overshadowed by the Master Narrative of Link, but she’s also always there, just a little out of sight, hiding in the shadows. And the darkness shall not be feared, because both light and dark are equally divine. Day and night, sun and moon, all work together to make up the cycles of nature. And it’s this truth that The Legend of Zelda yearns to admit, but cannot, because rediscovering this truth is the journey that The Legend of Zelda is about.

Link quests to be reunited with Zelda and, as such, Zelda becomes a symbol. She herself represents the primordial sacred state of the noösphere that art and shamanism alike are trying to get back to. The journey to get back to Zelda is not just Link’s, it’s not just The Legend of Zelda’s, it’s ours. Zelda is arcane knowledge and wisdom (indeed, the Triforce of Wisdom) available to the warrior shaman who has gained mastery of the the spirit world and the spiritual arts. She is an ideal state for us to aspire towards becoming, and some of us are skilled and wise enough to mantle her.

Link and Zelda are not the heroic knight and his beloved damsel waiting to be rescued, they are two manifestations of the same oversoul. Link and Zelda are, in fact, the same person. Zelda is the true self Link strives to reconnect with.

The game itself gives us the biggest clue to Zelda’s true nature: Entering her name as yours on the game’s file select screen takes you immediately to the “Second Quest”: A redesigned, overhauled and more challenging version of the game normally accessible only after completing the game once. After all, if you’re Zelda, you’ve already attained mastery. The adventure continues because there’s always things to learn and ways to better yourself, but you’ve transcended the boundaries of what the ritual was programmed to explore.

An argument could be made that this is something men need to understand and women don’t, because it’s a truth women should know innately. But it still strikes me as the faintest bit exclusionary: A spiritual quest women are denied participating in because of a lack of representation and identification. There really is no reason that a modern coming of age ritual shouldn’t induct women, because expression and enlightenment are things all people can strive towards. The physical and spiritual worlds have bearing on each other: What happens in one effects the other, and Link’s inability to present as Zelda has real world consequences.

But like all oral traditions, The Legend of Zelda evolves over time. As it gets passed down, each generation leaves its own distinctive mark on The Legend of Zelda, contributing to and reforming it in turn. It’s how legends and traditions live on and gain strength. And video games can be reinterpreted in a very material way, through remakes, re-releases and transformative fan games that build on and reconceptualize the original work.

The Legend of Zelda was built to be reinterpreted and retold. In a material sense, Zelda no Densetsu itself has been physically repurposed many times, and some of these incarnations have glorified and sublimated the original work to an even greater potential. Almost a decade after the original Famicom Disk System game, Nintendo partnered with online distribution service St. GIGA to create BS Zelda no Densetsu, an enhanced re-release of the original game for the Broadcast Satellaview.

The Legend of Zelda was built to be reinterpreted and retold. In a material sense, Zelda no Densetsu itself has been physically repurposed many times, and some of these incarnations have glorified and sublimated the original work to an even greater potential. Almost a decade after the original Famicom Disk System game, Nintendo partnered with online distribution service St. GIGA to create BS Zelda no Densetsu, an enhanced re-release of the original game for the Broadcast Satellaview.

The Satellaview was a satellite modem for the Super Famicom that broadcast episodic video game experiences to Nintendo’s console. Due to the nature of the system, Satellaview games only existed for as long as the signal was broadcast, so players would have to tune into the game like a television show and complete it within the duration of a given timeslot. So BS Zelda no Densetsu requires a mastery and understanding of time (particularly of presence), and an awareness of what was happening at any given moment. BS Zelda no Densetsu also finally gave players the option of a male or female avatar, based on the two mascots of St. GIGAS’ satellite service.

In 2014, after a decade of work and play testing, the definitive version of Lord Steak’s ROM hack of the NES port of Zelda no Densetsu was uploaded to the Internet. Entitled Shin Zelda Densetsu, the game is a fully overhauled and redesigned version of the original game with a wide variety of changes and updates, most notably the fact for the very first time, the player’s protagonist and avatar is none other than Zelda herself. The game itself is a complete reimagining of the original title on every level: The iconography is the same and the experience feels intuitively and intimately familiar, and yet it’s a new version of the legend all its own. The choice of name carries fitting power, as Shin Zelda no Densetsu can be understood to mean several different concepts, which can be read in English as either New Legend of Zelda, True Legend of Zelda, Pure Legend of Zelda or God Legend of Zelda.

Shin Zelda Densetsu targets a very different audience than Zelda no Densetsu did in 1986. Instead of a coming of age story for children (read boys) who have never seen something like this before, its a game that expects us to already know what The Legend of Zelda is. It’s a game perhaps first and foremost for those of us who grew up on Zelda no Densetsu and are looking to travel beyond to the next state, very fitting for a game starring Zelda. Shin Zelda Densetsu even positions itself, albeit halfheartedly and in a very knowing tongue-in-cheek manner, as being a direct sequel to the original Zelda no Densetsu.

But direct sequels in the world of video games, like in the world of oral tradition, are rarely quite so simple, and frequently anything but. Ultimately Shin Zelda Densetsu is a retelling of The Legend of Zelda by the next generation that builds upon the teaching of its elders with wisdom of its own, even as reaches all the way back to the primordial state to understand its own truth.

June 16, 2016 @ 2:40 pm

I’d heard the Super Mario Bros 3 theory, of course, but it had never even occurred to me that it could be extrapolated to encompass the entire series, even though Bowser’s participation implies this. The idea neatly explains the power dynamics of Peach’s repeated kidnapping and rescue too. Very interesting. Does any other work of serial fiction operate this way?

I was about to ask how the 3D games could also be theatrical performances, but then I remembered the Lakitu who films Mario’s adventures in Super Mario 64 – evidently the troupe got a TV deal.

June 16, 2016 @ 6:34 pm

In particular it illuminates the existence of Paper Mario–kamishibai was a form of Japanese traveling theater that was very commonplace and popular in the first half of the twentieth century, involving a series of static images painted on a scroll and displayed in sequence by the kamishibaiya, who would recite the story at the same time. It was popular enough that when television was introduced to Japan, it was initially called electric kamishibai!

So the idea of a traveling drama troupe having an alternate form in which their stories are told through papercraft makes a LOT of sense.

June 16, 2016 @ 11:16 pm

Electric Kamishibai is a wonderful name for a band.

Also… I clicked to reply and it set me up as “Jacob” revealing to me his e-mail address.

June 18, 2016 @ 1:28 pm

“Does any other work of serial fiction operate this way?”

Perhaps not the “reiterated storyline because it’s a different production of the same show” aspect, but classic Looney Tunes has a similar “the characters are actors” vibe. Bugs Bunny shows up in the time of the Vikings or Ancient Rome or a medieval castle, and Elmer Fudd or Yosemite Sam are there to play their established antagonist roles. Daffy Duck takes on various heroic guises from Robin Hood to Duck Dodgers, with Porky always playing his sidekick. (Particularly notable is “The Scarlet Pumpernickel”, which has a framing story of Daffy actually pitching the cartoon to Warner Bros.)

The Muppets might also count to an extent, although many of their works have been shows about making a show, which is a different dynamic.

June 21, 2016 @ 7:02 am

“It is not, I think, a great stretch to interpret video games as a modern form of ritualized shamanic practice.”

Absolutely, though being less of a computer gamer I really get that as my early forays into Roleplay Gaming led I think to me developing my interests in spiritual exploration also.