The Comprehensive History of Injustice

A guest post by Seth Aaron Hershman.

A guest post by Seth Aaron Hershman.

…the entire world might be poisoned. This, however, seemed unlikely, as the world, no matter how monstrously it may be threatened, has never been known to succumb entirely.

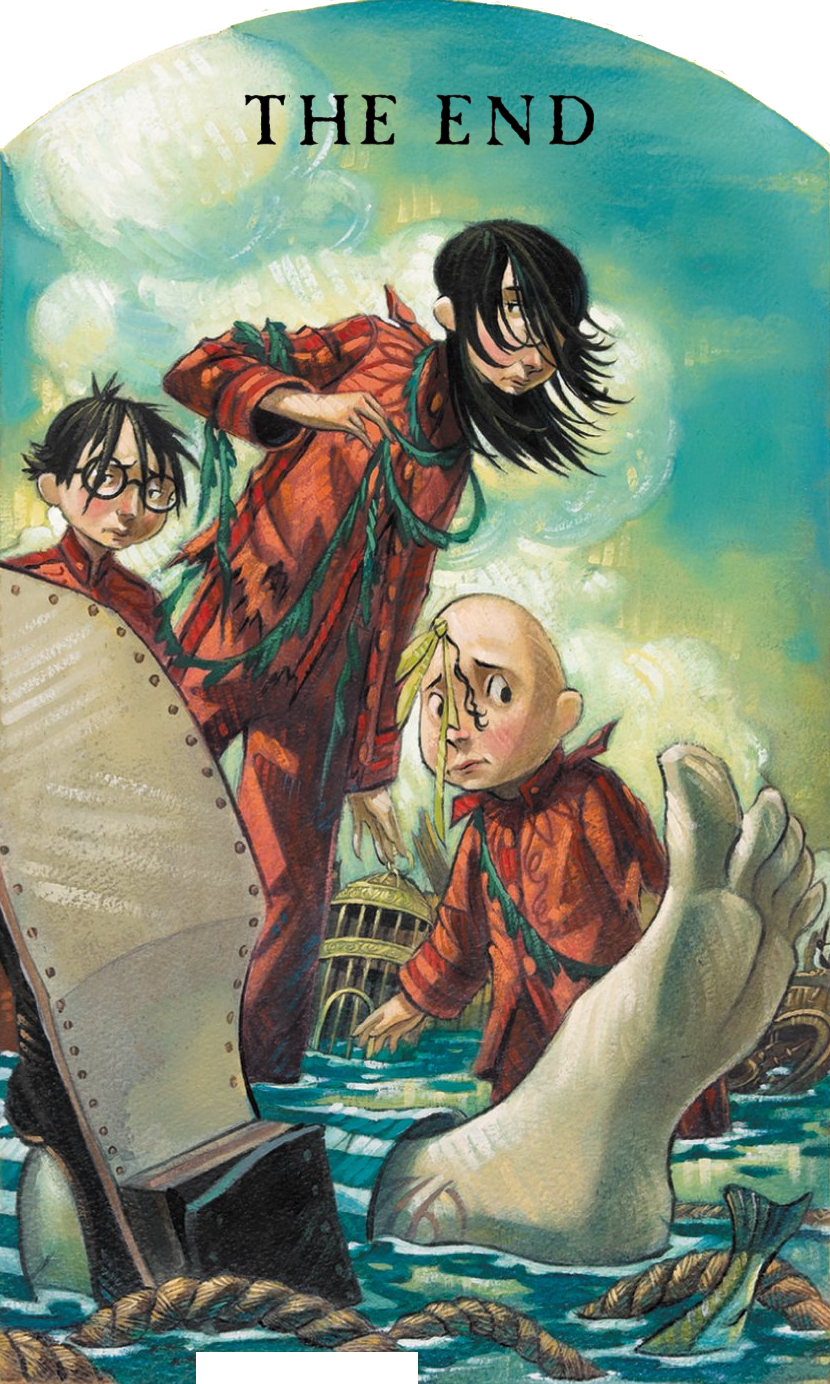

A Series of Unfortunate Events is a book series, and currently a Netflix show, about three orphans, Violet, Klaus, and Sunny Baudelaire, who are chased from place to place by a man named Count Olaf who manipulates (and if necessary knocks off) anyone who might try to take them in so that he can have them–and their inheritance/trust fund–for himself.

Count Olaf is a rich man looking to get richer, who relies on transparent lies and cheap theatrics to get his way, casually uses and discards people, has a roughly third-grade literacy and vocabulary level, and works in entertainment.

It’d be easy to go that route, wouldn’t it?

The issue of timeliness is a difficult one for A Series of Unfortunate Events, a franchise which actively avoids setting itself in a specific era in a way that should be familiar to fans of, say, Archer or Batman: The Animated Series. Because the series goes out of its way not to take place in any particular time, it’s difficult to pin whether the obvious allegory is an act of authorial intent or merely a fortunate coincidence. (One could argue that the fact that these books were written a decade ago makes it a forgone conclusion, but it’s not like our president was anonymous in at the turn of the century.)

In fact, it’s difficult to pin anything. Which is perhaps part of the point–anchored to no time, the series is able to make a broader point about how all times and all eras are susceptible to the transparent lies and cheap theatrics of rich men looking to get richer.

The rich men themselves are not really the point of the series–after all, most of the series’ characters are comfortably well off, and our leads are victimized specifically because Olaf wants at their sizable inheritance. In fact money itself seems to be a little besides the point. The bigger problem is self-absorption, and the inherent flaws in systems built out of self-interest.

The reason Olaf’s schemes always succeed until the last moment is that self-possession is a character flaw on the part of all who take the Baudelaire orphans in. Their uncle Monty knows well enough to suspect “Stephano” but gets hung up on the idea that his new assistant is after his scientific discoveries rather than his newly aquired children. Their aunt Josephine is ruled by her intense phobias and too obsessed with her tragic past to suspect someone who’s obviously manufactured a similar one for the sake of sympathy. And Mr. Poe, the man in charge of the Baudelaire estate, is constantly talking about how important it is that he get back to his other business matters before he has the chance to do even the most basic checking-up on whatever circumstances he’s dumped the children in this time.

This tendency towards self-absorption seems to have ballooned in modern politics. In the wake of a recent events people are fond of pointing out that everyone seems to have put their own wants and needs out ahead of putting a certain lunatic in the ground–the news media wanted ratings, the Democrats wanted a Clinton presidency, the other Republicans wanted to look more respectable than the opposition. But in actuality this is the history of politics, isn’t it? In the run up to the election many people were eager to point out, for instance, how a disunified front always puts the opposition in power, no matter what side you’re on–Lincoln and Bush both won roughly this way.

The matter of method is a crucial one to A Series of Unfortunate Events. The Baudelaires are often told that they’re self-absorbed and short-sighted for suspecting Olaf is lurking around every corner–the only difference between them and most of the people they’re in the care of is that the Baudelaires are right. Eventually deciding to take matters into their own hands after being let down time and time again, end up going down a path where they themselves need to use disguises and deceit to get their way.

In a sense, this is the sort of all-sides-are-awful centrist nonsense that permeates, say, South Park, but author Daniel Handler is smart enough to make sure that, regardless of inherent vices on all sides, there’s a clear-cut sense of good and evil. Yes, it’s a broad, tongue-in-cheek sort of good and evil in which both sides, apart from the orphans, are severely lacking in common sense, but as the series becomes more fixated on pathos and mystery and less on being a bizarre take-off on gothic literature, it refuses to break down. The Baudelaires may be acting in ways that parallel them to the villains, and their adolescent brains might not deal with those actions well, but they are still firmly sided with by the narrative.

The guardians, of course, don’t get as sympathetic treatment, but even when they’re incompetent the Baudelaires still sympathize with them and their demise is depicted as undeserved. Being self-absorbed because you want credit for discovering a snake, or because you have PTSD from your husband’s death, is fair and reasonable. It just means that, perhaps, people should be a bit careful about what they put you in charge of, especially if that something is children. Similarly, if your political party wants to improve reproductive rights and provide health care and give the oppressed more rights, but also can’t be bothered with caring about who they bomb or who starves to death, they should perhaps not be put in charge of the bombs and the food.

More astutely, Handler identifies a common historical problem with trying to dismantle these systems when you’re just an ordinary person. You can’t. Violet, Klaus, and Sunny are never given the ability to permanently take Olaf down. They can point him out. They can use their extensive knowledge, wits, and skills to prove he’s up to something. Never to loudly, and never too obviously, because he’s constantly got a knife to their necks. But in the end their only option for ending him permanently is to hand him over to the same system that’s disinterested in noticing him before the problem gets as bad as it has. And that’ll never happen. He always escapes.

Perhaps it’s inaccurate to claim that A Series of Unfortunate Events is totally ahistorical. Everything has to cap out somewhere. Certainly it’s not alocational, a made-up word which here means “not rooted to any particular place”–it’s fairly obviously set in a cross between United States or England. The problem is that committing a violent coup in either place is morally frowned upon these days. The United States specifically hasn’t had a meaningful one in about a century and a half. The fact that the Baudelaires don’t rise up, slaughter Olaf and conquer their corner of the world by force puts a cap on whose politics it can, meaningfully, be about.

The obvious argument here is that this isn’t, in fact, a limitation of the book’s politics. After all, it’s a series for children. No matter how many characters suffer gruesome deaths, no matter how badly the system breaks down, no matter how many times the series informs us that bad actions are sometimes necessary for good results, “plucky, precocious children outright slaughter an evil man” is never going to be part of the recipe.

Fair dues. Except for the part where they murder everyone else.

Sure, they try to warn their victims. Sure, it’s mainly just a case of collateral damage. But no matter how you frame it, the Baudelaires, in the penultimate book, are directly responsible for the murder of basically every single character in the entire series besides themselves and Olaf. Trapped in a kangaroo court for a manslaughter charge along with Olaf, their solution is to burn down the hotel with everyone inside in order to ease their escape, and with Olaf being an old hand at this sort of thing they decide to cooperate with him.

We’re never told how, or even if, they rationalize this to themselves. No clear line of moral justifications, nor outright objections lasting more than a few sentences, make it into the narrative. The Baudelaires find themselves adrift in a mental landscape of moral greys and self-doubt, but it never resolves to anything. Lemony Snicket, our narrator and always the quickest to pass judgment, for once restrains himself to a non-editorialized tone. The only thing we have to go on is that the Baudelaires continue to be depicted as sympathetic actors after they’ve committed arson.

It is not said that burning the system down is a good thing. Only that doing so does not, inherently, make you a bad actor. Through this one act, the cap is blown off the top of which history the series can be about. Sure, it’s always going to look and talk like US/Britain crossbreed, but it’s now a US/Britain crossbreed that can, within the narrative’s scope, be destroyed by good actors. The series now points not towards the past, but towards a future.

The Baudelaires spend the last book apart from society, and within the scope of the novels we never find out what their world will look like when they return. The island village they find themselves in instead suggests a simpler society with rules and rulers that are just as cruel and unjust as the ones they left. It’s not unlikely. A Series of Unfortunate Events can be about so many times because society fundamentally never changes.

It’d be nice if the series provided an answer to this, figured out how to end the cycle and build a better world. Or even just threw its hands up and decided humanity needs to die. Maybe that’s a bit much to expect from a children’s series, or literature of any stripe. It’s not the only thing the series leaves hanging.

“If we leave,” Sunny asked, “what will we find?”

The Baudelaires fell silent. …

January 20, 2017 @ 1:07 pm

Lovely to see this series on EP.

I think I have to reread the end of Penultimate Peril now, though.

January 22, 2017 @ 9:21 am

Excellent piece. I’ve been enjoying the series a lot, especially for its general faithfulness in adapting the books for the screen.

August 8, 2017 @ 4:28 am

Get Upto 80% Off On Online Shopping in India.Find the top Shopping apps and games for Android devices.Build Android App online or make your own free Google Android App online.

August 9, 2017 @ 4:36 am

Nox App Player offline installer for PC is a latest Android emulator. Free download Nox App Player for Windows 10/8.1/8/7 xp, vista & Mac Laptop/PC. Nox App Player Download for PC, Laptop.Nox App Player for Windows 10 or Windows 8.1/8/7/XP or Nox App Player for Mac. Nox App Player Free Download on …