The Eyes Have it (Doctor Who/The Girl Who Died)

So I was wondering what I was going to write for this week’s essay. I knew it would be on Doctor Who symbolism, but what? The TARDIS as a Religious Object? The Circle in the Square? Eyes? Something on Mirrors, perhaps? I eventually decided I’d let Saturday’s episode decide it for me. As such, I was rather taken with the fact that the opening image was a close-up of a singular Eye. Upside down. In an episode which features a Mirror reflection and an invocation of the TARDIS as a vehicle of the gods at its emotional climax (which was distinct from the Faux Resolution of defeating the Mire). But the Eye came first, so the Eyes have it.

So I was wondering what I was going to write for this week’s essay. I knew it would be on Doctor Who symbolism, but what? The TARDIS as a Religious Object? The Circle in the Square? Eyes? Something on Mirrors, perhaps? I eventually decided I’d let Saturday’s episode decide it for me. As such, I was rather taken with the fact that the opening image was a close-up of a singular Eye. Upside down. In an episode which features a Mirror reflection and an invocation of the TARDIS as a vehicle of the gods at its emotional climax (which was distinct from the Faux Resolution of defeating the Mire). But the Eye came first, so the Eyes have it.

It turns out there’s a wealth of Eye imagery to examine in The Girl Who Died. There’s the aforementioned opening image—the first time we’ve had an Eye closeup turned upside down. There’s a closeup of the wooden dragon’s eye, we’ve got Odin to cover, and of course the cleaving of the Sonic Sunglasses such that they become like an eyepatch.

Interestingly, there’s plenty of context to choose from. I mean, this season has already featured a variety of “eye” symbolism, in an era that’s regularly played with the imagery, which was already established since the beginning of the Revival, not to mention the fact that there are implications from the Classic series and filmography in general. And, of course, the Eye is a symbol that precedes all this. So first, let’s go back and look at the Eye’s semiotics, and then survey its use in Doctor Who before returning to The Girl Who Died.

Eye See You

First off, unlike The Chair Agenda, the symbolism of the Eye is relatively straightforward. The eye is one of the most important sense organs. So of course it’s used to mean “perception,” but it goes further than that. Vision itself is one of our primary metaphors for “knowing.” We see what other people mean, for example. In asking for clarification on something, we want some light shed on the subject. To communicate is to show something. We talk about knowing something from someone else’s perspective as seeing from their point of view. The attempt to gain knowledge is looking for the truth. Ignorance, on the other hand, is not being able to see, to be blind. To keep someone from learning something is to hide it, to cover it up, perhaps even to pull the wool over their eyes.

The metaphor of Knowing Is Seeing is so intrinsic, it informs all kinds of “knowing.” For Descartes, it was all about “the light of reason.” In this extended metaphor, Reason is like a Homunculus sitting in the mind, looking at all the Ideas therein as if they were objects on a screen. While indeed it’s quite likely that the visual cortex in the brain handles some of what we call thinking – from pulling up a picture of an old memory to visualizing the future – the truth is much more complex.

But even when we move away from “observation” as the root of learning (or even Science) and consider mystical or religious impulses, the metaphor still holds sway. Enlightenment and Illumination both spring to mind. “Awakening” implicitly likens the expansion of the mind and indeed consciousness itself to the opening of one’s eyes after a period of sleep. But now we get into something altogether more contradictory. For in this instance, to “see” in a spiritual sense actually means to disavow the physical sight of one’s eyes. In the myth of Odin, for example, the god visits Mímir, a being known as “The Remember,” and who guards the Well of Wisdom. Odin has to sacrifice one of his eyes to drink from the well, which is why he’s depicted as having only one eye. But the insight he gains from this sacrifice, that is true wisdom.  The upshot, then, is that there is a second reality, one not visible to the naked eye, one that isn’t “objective.” We aren’t meant to “judge a book by its cover,” so to speak, but to peer behind the veil, be it of the Universe or an individual soul, in order to understand what is “true.”

The upshot, then, is that there is a second reality, one not visible to the naked eye, one that isn’t “objective.” We aren’t meant to “judge a book by its cover,” so to speak, but to peer behind the veil, be it of the Universe or an individual soul, in order to understand what is “true.”

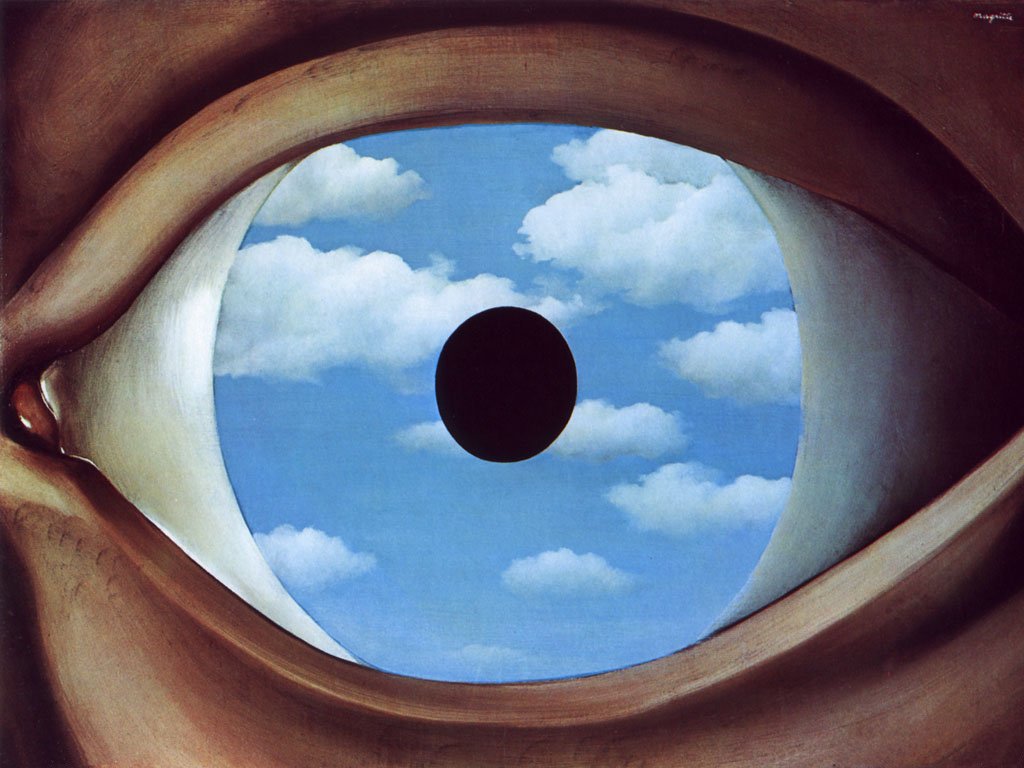

When the 12th Doctor begs Clara to “see” him in Deep Breath, he’s talking about his insides, not his outsides. He’s asking her to look with her “third eye” as it were. The “eye of the heart,” perhaps. “False Mirror” by René Magritte aptly captures the essence of this conception. And this in turn points to how we consider the eyes as “windows” to the soul. We don’t just look out of them, we look into them. Looking into someone’s eyes is an act of intimacy. It can be piercing. And this is conveyed in the art of film, cinematically, through the conceit of the close-up. The closer we see someone, the more “intimate” the shot is meant to be. Presented with an extreme close-up on the eyes, we are given a look into the interiority of a character.

How Do Eye Look?

In light of this, and especially in the context of Doctor Who, we have to consider what the Eye motif conveys when it comes to monsters. Monsters are an interesting case – the word “monster” derives from the Latin monstrum which referred to “divine omens and portents” as well as “abnormal shapes.” At the root of the etymology is monere which means “to warn.” So monsters are also about perception, of a sort, a way of looking at the world and trying to discern the future. Or, in modern times, to discern our own psychology.

Eye-monsters don’t follow a particular type or have a particular meaning, historically speaking. The Cyclopes of Greek mythology, for example, are known more for being giants of brute strength; that they have a singular giant eye in the middle of their foreheads is not particularly indicative of their nature. Others might have an “Evil Eye,” like Balor of Irish mythology, whose singular eye, when opened, would cause all manner of destruction, especially drought; perhaps a reflection of the Sun as being a baleful “eye in the sky.” Azrael, an “angel of death” in the Abrahamic religions, is in one form completely covered with eyes, one for each person living on Earth. Here, the eye represents the individual spirit.

This lack of thematic coherence is likewise prevalent in the Classic series of Doctor Who. Consider the Monoids, “happy slaves” who become despotic rulers after meeting the Doctor. Coming at the end of the frankly awful Wiles run of Hartnell’s tenure, the Monoids represent little more than the fears of post-colonial Britain; the best we can say about their Eye iconography is that they’re depicted as being short-sighted. But contrast to Alpha Centauri, toponymously named, a friendly alien in the Peladon stories. While Centauri might be fearful and a bit misogynistic (despite being hermaphroditic), the character isn’t stupid, and indeed appears to have at least some political acumen, having achieved the title of Galactic Federation Ambassador by the second visit to Peladon.

This lack of thematic coherence is likewise prevalent in the Classic series of Doctor Who. Consider the Monoids, “happy slaves” who become despotic rulers after meeting the Doctor. Coming at the end of the frankly awful Wiles run of Hartnell’s tenure, the Monoids represent little more than the fears of post-colonial Britain; the best we can say about their Eye iconography is that they’re depicted as being short-sighted. But contrast to Alpha Centauri, toponymously named, a friendly alien in the Peladon stories. While Centauri might be fearful and a bit misogynistic (despite being hermaphroditic), the character isn’t stupid, and indeed appears to have at least some political acumen, having achieved the title of Galactic Federation Ambassador by the second visit to Peladon.

We’re on more familiar ground, however, with The Greatest Show in the Galaxy, which trades on the explicitly Norse mythology of Ragnarok. Here we have an abundance of Eye symbols that function as expected – Eyes on kites up in the sky that are used for surveillance; an Eye in a Crystal Ball, read by a Psychic at the Psychic Circus as a portent to obey the Gods; and a giant Eye deep in a Well, an invocation of Odin, to whom the Doctor is likened (he draws The Hanged Man from a Tarot reading at one point); the Well is seemingly a portal to the realm of the Gods themselves. Interestingly, restoring a broken medallion bearing the iconography of the Eye restores the mind of a supporting character; that medallion, when thrown down the Well, ends up in the Doctor’s hands, and helps him to defeat the Gods of Ragnarok (he uses it as a mirror, natch).

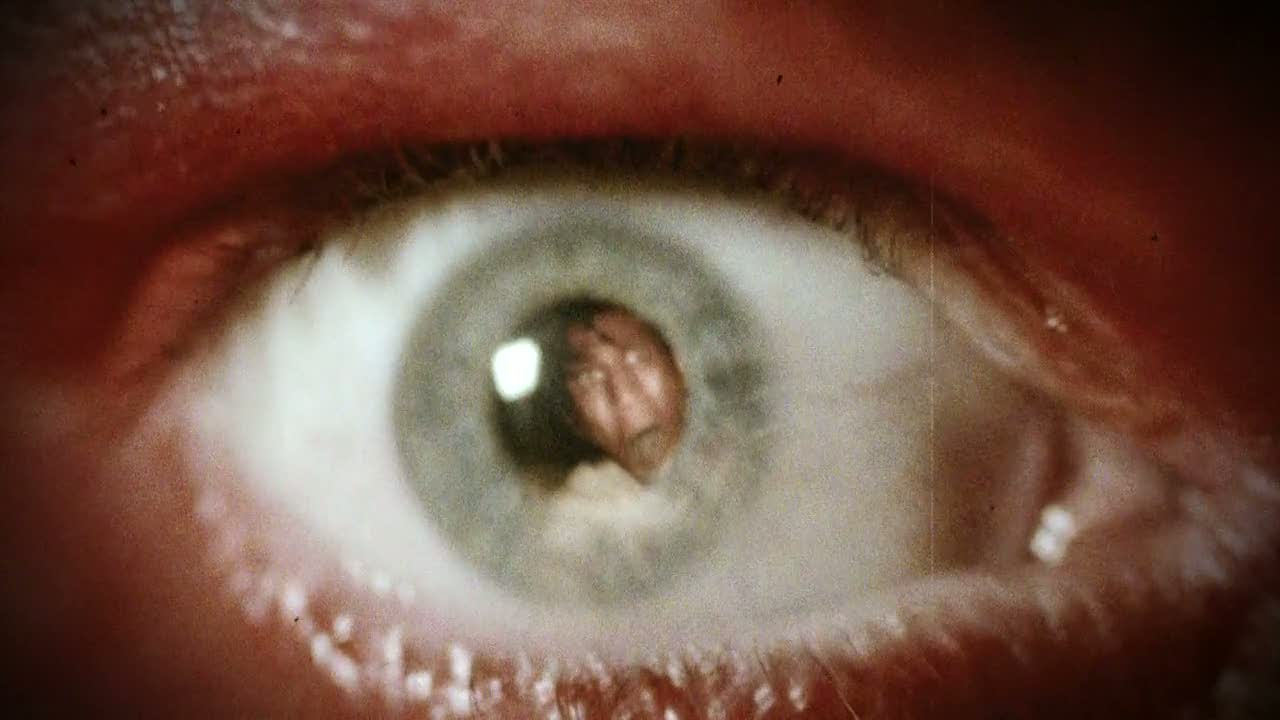

One of the most striking examples of Eye symbolism in the Classic series, however, is in Kinda. Here the Eye isn’t part of a monster, but a way of accessing the interiority of a character, namely Tegan. Several times the camera zooms into her eye, until the frame is pitch black where we light upon Tegan and the Mara characters she encounters. Considering that she’s dreaming at the time, the camera is functioning symbolically: these images aren’t literally in her eye, but in her mind. Her mind’s eye.

Which brings us back to the Cartesian Theatre of the mind, and the notion that the mind is a “person” – a homunculus – who views the events projected from the eye, and thereby informs the self of what is seen. It’s a fallacious argument, of course – if the homunculus has to look at the Cartesian Screen, with its own eyes, we end up with a case of infinite regression. Metaphorically, however, this can be quite rich, as the depiction of the Homunculus can be used to provide insight into what’s going on inside the mind. That Tegan encounters a manifestation of the Mara – Dukkha – who ends up gaining control of her consciousness can be read as succumbing to a darker archetypal aspect of the self. It’s a conceit that actually informs a great deal of the Revival’s imagery as well.

Beyond the See

While there is one particularly interesting use of Eye symbolism during RTD’s tenure (which we will attend to later), it’s in the Moffat era that the Eye is ubiquitous. Right from the get-go in The Eleventh Hour, we’ve gotten eyes up to, well, our eyeballs. Their use is not gratuitous, either, but kith and kin with the era’s thematic concerns, and in general used appropriately to express those concerns.

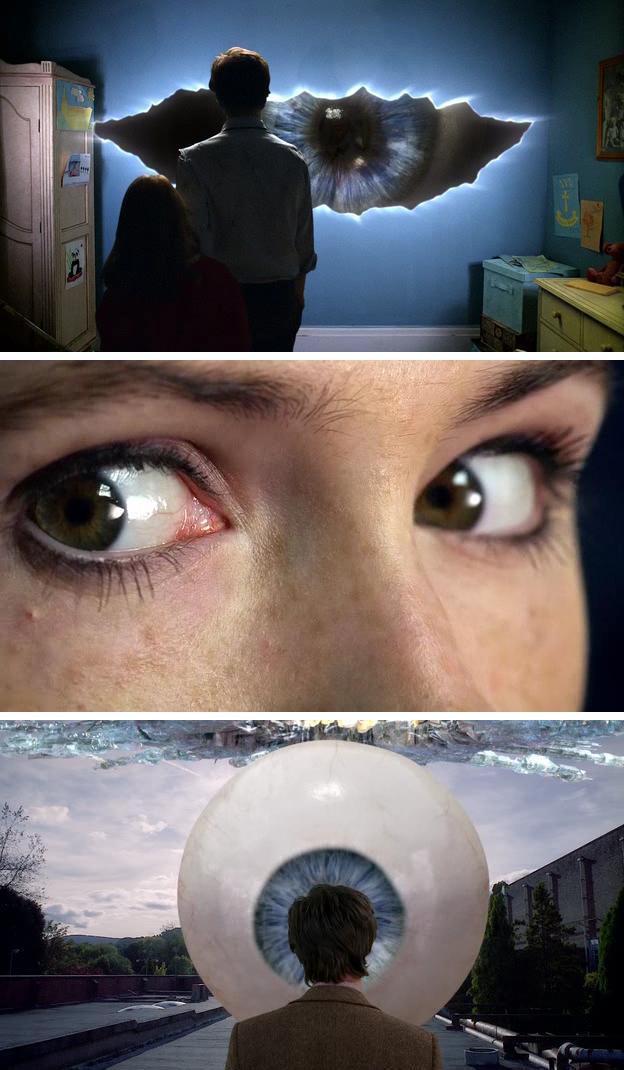

One of those concerns is in regards to Perception, Insight, and Memory. The plot of Eleventh Hour, for example, hinges in part on the existence of “perception filters” which have the effect of directing one’s attention away to prevent something or someone from being perceived. The Doctor teaches Amy how to overcome perception filters by looking out of the corner of her eye, which is depicted by an extreme closeup of Amy’s eyes. Given this is also Amy’s introduction to the audience, this sort of shot also establishes intimacy between the audience and the character.

That’s not the only scene that plays with the characters’ perceptions and that of the audience as well. Thecamera is used at various points to critique things like the Male Gaze, or, in a similar shot to Kinda, to dive into the Doctor’s eye to get a subjective interpretation of how he observes the world, and hence insight into his psychology.

Eleventh Hour also has an Eyeball Monster: the Atraxi, which are depicted as giant Eyeball Snowflakes flying in the sky, which take on the role of Judgment, determining what constitutes a crime and what does not. They in turn are evaded by Prisoner Zero, a shapeshifter that takes on the aspect of comatose people, accessing the subconscious mind to create a false image, often one with a “monstrous mouth.” Interestingly, the first appearance of the Atraxi is within a mouth-shaped Crack in the wall. But the best moment is at the end, when the head of the Doctor fills up the pupil of an Atraxi Eye. The Doctor has gotten “into the head” of the Eye, convincing it to run. Which is terribly apt. After all, the “pupil” of the eye derives from the Latin pupilla, which means “little doll,” referring to the reflection of ourselves that we see in each others’ eyes, and which likely contributes to the Homunculus theory of consciousness.

Eleventh Hour also has an Eyeball Monster: the Atraxi, which are depicted as giant Eyeball Snowflakes flying in the sky, which take on the role of Judgment, determining what constitutes a crime and what does not. They in turn are evaded by Prisoner Zero, a shapeshifter that takes on the aspect of comatose people, accessing the subconscious mind to create a false image, often one with a “monstrous mouth.” Interestingly, the first appearance of the Atraxi is within a mouth-shaped Crack in the wall. But the best moment is at the end, when the head of the Doctor fills up the pupil of an Atraxi Eye. The Doctor has gotten “into the head” of the Eye, convincing it to run. Which is terribly apt. After all, the “pupil” of the eye derives from the Latin pupilla, which means “little doll,” referring to the reflection of ourselves that we see in each others’ eyes, and which likely contributes to the Homunculus theory of consciousness.

So there’s a coherence to the Eye symbolism in Eleventh Hour, and it pretty much plays out in other  Moffat-era stories. When Amy is subjected to brainwashing in The Beast Below, for example, we see images play out across her eyes, a conceit that’s repeated later in the episode when she remembers what she saw, consequent with an extreme closeup of her eye. Or take Amy’s Choice, where there are monster-eyeballs lodged in people’s mouths, reiterating the symbolism of the season opener, and obliquely related to the episode’s themes of, yet again, the ability to perceive reality from nightmare.

Moffat-era stories. When Amy is subjected to brainwashing in The Beast Below, for example, we see images play out across her eyes, a conceit that’s repeated later in the episode when she remembers what she saw, consequent with an extreme closeup of her eye. Or take Amy’s Choice, where there are monster-eyeballs lodged in people’s mouths, reiterating the symbolism of the season opener, and obliquely related to the episode’s themes of, yet again, the ability to perceive reality from nightmare.

In the Crash of the Byzantium, we return to the Homunculus conceit of the Eye. Weeping Angels are creatures of perception – they only move when you can’t see them. But look at them too long, too hard, and they can creep into your mind. In the second part, we get a series of images where Amy and an Angel crawl through an eye-like aperture, foreshadowing the appearance of an Angel in Amy’s eye. And this very much serves to indicate that Amy’s mind is being hijacked by the “homunculus” of an Angel. Interestingly, this hijacking occurs during Amy’s first encounter, when she “sees” that there’s a blip in the tape loop from which the Angel emerges. It’s also in this episode that we get the wonderful line, “The eyes are not the windows of the soul. They are the doors.” (Funny, but the etymology of “window” is Norse, and translates as “wind-eye.”)

The Lodger also plays with perception filters and eye symbolism. The old Silence time-ship uses a perception filter to make everyone think Craig’s house has a second floor; it does not. The Doctor uses a perception filter to encrypt his communications with Amy, so that Craig only hears gibberish. And the Doctor is trying to live with Craig without revealing who he is; he’s “faking it” as human. But when it comes time to make his big Reveal, we get yet another shot of the camera zeroing in on the Doctor’s eye, suggesting yet again the infinite recursion of the Homunculus as behind each Eye is a Doctor, and through that Doctor’s eye another Doctor, and so on, and so on. Transferring this information occurs by the Doctor and Craig banging their heads together, specifically, though, their foreheads, the location of the Third Eye. In a lovely touch, the final image presented is one of Amy floating in space: an image of Ascension.

The Lodger also plays with perception filters and eye symbolism. The old Silence time-ship uses a perception filter to make everyone think Craig’s house has a second floor; it does not. The Doctor uses a perception filter to encrypt his communications with Amy, so that Craig only hears gibberish. And the Doctor is trying to live with Craig without revealing who he is; he’s “faking it” as human. But when it comes time to make his big Reveal, we get yet another shot of the camera zeroing in on the Doctor’s eye, suggesting yet again the infinite recursion of the Homunculus as behind each Eye is a Doctor, and through that Doctor’s eye another Doctor, and so on, and so on. Transferring this information occurs by the Doctor and Craig banging their heads together, specifically, though, their foreheads, the location of the Third Eye. In a lovely touch, the final image presented is one of Amy floating in space: an image of Ascension.

Since then, we’ve gotten the “accusing eyes” of The Almost People, the glass  eyeball of Night Terrors and yet another allusion to perception filtering/a fake reality, the Doctor being captured in the Eye of a giant Dalek statue, and of course the recent “possession” of people’s souls by the Fisher King after reading his enchanted runes – easily understood given the intense close-ups of Eyes in The God Complex, which was used to indicate the “awakening” of finding one’s room, where fear and faith became one. In The Wedding of River Song, we get “eye-drives” that are functional eye-patches, at once blinding and visionary in their ability to retain the memory of a monster that can wipe memories, and of course the Doctor’s admonition to “look in my eye,” where River find his very own homunculus.

eyeball of Night Terrors and yet another allusion to perception filtering/a fake reality, the Doctor being captured in the Eye of a giant Dalek statue, and of course the recent “possession” of people’s souls by the Fisher King after reading his enchanted runes – easily understood given the intense close-ups of Eyes in The God Complex, which was used to indicate the “awakening” of finding one’s room, where fear and faith became one. In The Wedding of River Song, we get “eye-drives” that are functional eye-patches, at once blinding and visionary in their ability to retain the memory of a monster that can wipe memories, and of course the Doctor’s admonition to “look in my eye,” where River find his very own homunculus.

This use of recurring motifs can be combined with other motifs. For example, when we see Missy’s left eye reflected in a mirror in The Magician’s Apprentice, followed by a reflection of Clara’s face in the left eye of the Doctor’s glasses, we can reasonably anticipate a juxtaposition of Clara and Missy, which we subsequently get in The Witch’s Familiar – for Clara has her dark side (she wants a pointy stick) and Missy wants a certain kind of companionship from the Doctor – the mirror being a symbol of Identity, of course. All of which is to say, once you’ve established a motif, you can adapt it for subsequent effect, letting the previous instances carry all kinds of connotative weight.

Homunculii

So, take the recurring motif of someone appearing in the Eye, like with Amy and the Angel in her eye. This helps to inform us of other instances of the same motif, and may even help us to reinterpret past episodes before the connotations became apparent.

The next reappearance of a person in Red shown in someone’s eye comes in Let’s Kill Hitler. Here we have a literal instance of the metaphor: tiny people inside a larger “person” who are actually running the show. Red, we should note, is a part of the alchemical lexicon: rubedo is the final stage of the alchemical 09-42-21].jpg) Great Work, which is a stage of synthesis. Like much of Doctor Who, this is somewhat subverted: the people running the Tesselector aren’t “integrated” through some kind of ascension process, so much as playing at being an Old Testament god. They go around punishing historical figures.

Great Work, which is a stage of synthesis. Like much of Doctor Who, this is somewhat subverted: the people running the Tesselector aren’t “integrated” through some kind of ascension process, so much as playing at being an Old Testament god. They go around punishing historical figures.

But this changes once Amy ends up inside the Tesselector, after it has taken her appearance and become her “mirror.” She is, of course, dealing with the loss of her child, which she handles in part by repression. Once she’s “inside her own head,” so to speak, the inside becomes the outside, and the “critique” by some quarters of Amy’s emotionlessness in the face of her tragedy becomes blatantly apparent. Only when “her head” becomes Empty (thanks to the Grace of the holy ghost of the TARDIS, granting salvation with Melody at her controls) can the monster-mirror be used to full effect, letting Melody Pond know exactly who River Song is.

Into the Dalek features an interesting inversion of the motif – here we see Clara and the Doctor, tiny people, crawling into the Eye of a Dalek. Clara’s the one in Red here, her shirt bedecked with Eyes. It’s her alchemical wisdom that guides the Doctor to help the Dalek remember the glorious event (the birth of a star) that made it question its very purpose in life, and set it on a path (albeit twisted) of material social progress.

Into the Dalek features an interesting inversion of the motif – here we see Clara and the Doctor, tiny people, crawling into the Eye of a Dalek. Clara’s the one in Red here, her shirt bedecked with Eyes. It’s her alchemical wisdom that guides the Doctor to help the Dalek remember the glorious event (the birth of a star) that made it question its very purpose in life, and set it on a path (albeit twisted) of material social progress.

That imagery plays on what came before in Asylum of the Daleks, which features Ms Oswald again wearing Red, within an eye motif.

Asylum is of course an Ascension story, twice over. On the one hand we’ve got the Doctor trying to activate the Teleport system so he and the Ponds can escape up to the Dalek ship (and the TARDIS therein), and the Doctor is certainly seen within the “eye motif” of the Teleport itself while he effects some repairs.

Oswin’s ascension is much more metaphorical. She’s been converted to a Dalek, but retains her humanity by believing that she’s still shipwrecked and awaiting rescue, fending off the Daleks all the time. But when she’s presented with the truth, she still overcomes, still retains her humanity, and sacrifices her life to save the lives of others as proof. In so doing, she’s granted the “self awareness” to look directly into the camera, with a bit of a smile, as if she’s remembered exactly who she is. So in this context, at least, by “ascension” we also mean self-realization, a cross of self-consciousness and enlightenment and efficacy in the world (social material progress).

For contrast, though, I must offer up The Crimson Horror. It’s a very interesting episode, perhaps Mark Gatiss’s best, and it’s absolutely refulgent with alchemical motifs. More importantly, however, it offers a  kind of subversion of the motif I’ve described. We certainly get plenty of “Red Person in the Eyeball” images, but here it’s made starkly literal, so much so it’s incorporated into the plot.

kind of subversion of the motif I’ve described. We certainly get plenty of “Red Person in the Eyeball” images, but here it’s made starkly literal, so much so it’s incorporated into the plot.

Likewise its use of other alchemical symbolism and indeed phrases. Mrs Gillyflower calls her scheme the “Great Work,” and invokes a “Golden Dawn,” harkening to the very real Order of the Golden Dawn, a Hermetic order devoted to studying the occult. Her plan is to send a rocket up in the air to release the “crimson horror” and thereby forcing everyone to participate in the rubedo stage of an alchemical working. Hell, she dips her converts into the stuff, all in devotion to an imagined “perfection.” Thanks to the efforts of the costuming department, we see that those who survive her deadly venom end up silvery and white, a recognition of the albedo stage, while she and her minions (the people in charge) are all dressed in black, a sop to the nigredo stage. Note that these stages end up being reversed. But even here there’s an ascension – Ada, the daughter, also dressed in silvery Hermetic colors, her albedo eyes blinded by experimentation, learns the truth of who she is in her mother’s Red room, and fights back as part of her emancipation.

All this is really part and parcel of Moffat’s vision for the show, which we first saw back in the Davies era, at the moment it became known to all that Moffat would be the next showrunner. So yes, we have to go back to The Library to see where it all began. The Library has some of the clearest Ascension imagery ever produced by the show. This is where River Song sacrifices herself to save not just the man she loves, but thousands of strangers, too. She ends up bathed in the white light of the “afterlife” of the Library, ironically now positioned to live a life in the “Ordinary World.”

But we are not concerned with River’s ascension here. Rather, we are concerned with the Little Girl – Charlotte Abigail Lux, or CAL. First, the relevant imagery: at one point we see her figure curled up in an Eye motif on the floor. In the other, we realize that all of her trips through the Library are actually facilitated by a Wooden Eyeball that doubles as a security camera. The “pupil” of the Wooden Eye bears the same logo as the rug on the wood floor upon which Charlotte falls. She’s the Girl in the Eye.

But we are not concerned with River’s ascension here. Rather, we are concerned with the Little Girl – Charlotte Abigail Lux, or CAL. First, the relevant imagery: at one point we see her figure curled up in an Eye motif on the floor. In the other, we realize that all of her trips through the Library are actually facilitated by a Wooden Eyeball that doubles as a security camera. The “pupil” of the Wooden Eye bears the same logo as the rug on the wood floor upon which Charlotte falls. She’s the Girl in the Eye.

She’s got an interesting name. Charlotte is the female diminutive of Charles, which simply means “man”; ergo, Charlotte pretty much means “little girl.” Abigail comes from the Hebrew for “Father’s Joy” or “Father is Joy,” and Lux means “light.” So, she’s the Little Girl of Joyful Light.

More importantly, though, is Charlotte’s role as a savior. This is reiterated several times throughout the story – she “saves” people (“I have to save,” she says) quite literally to a hard drive, then sets them up in a virtual reality afterlife that might as well be Heaven – and this is even more impressive considering it’s the Library of everything ever written, a veritable Akashic Records, but located on a technological plane as well as the astral one (such a convergence might be termed a “plane crash” for you LOST fans). Even better, Charlotte is a “perfect” savior. She passes no judgment. Which rather falls in line with the notion of Christ the Advocate, who advocates for all of humanity. And so by saving everyone, regardless of whether they are “deserving” or not, she becomes a source of Mercy and Grace.

Eye in the Sky (ascension)

Sometimes we get images of Ascension that are big. I mean, vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly, big, much bigger than that “long way down the road to the chemist’s” big. What we get in The Big Bang is probably as big as it gets. Here we are presented with an Eye in the Sky, which is about as close as we’ll ever get to a literal depiction of the Divine in Doctor Who. This is the fire of an exploding TARDIS, which is exploding at every point and moment throughout the Universe. And juxtaposed with that, wearing a Red hat, is the Doctor. He flies the Pandorica into the “eye of the storm” (a phrase invoked twice in the episode), and releases a “memory” of the Universe that is then transmitted by the “light.” In so doing, he “reboots” the Universe, which is to say, he performs a Universal Resurrection. Quite literally. And, you know, this all done by putting himself into that Eye!

to a literal depiction of the Divine in Doctor Who. This is the fire of an exploding TARDIS, which is exploding at every point and moment throughout the Universe. And juxtaposed with that, wearing a Red hat, is the Doctor. He flies the Pandorica into the “eye of the storm” (a phrase invoked twice in the episode), and releases a “memory” of the Universe that is then transmitted by the “light.” In so doing, he “reboots” the Universe, which is to say, he performs a Universal Resurrection. Quite literally. And, you know, this all done by putting himself into that Eye!

Death in Heaven presents us with some very similar imagery. Again we have a fiery eye up in the sky, but this time it’s an eye that’s created by Danny Pink (oh dear, he gave that cloud “pink eye”) when he and all the resurrected Cybermen ascend up into the sky to destroy the Dark Water that will give false resurrections to everyone. For to be an immortal Cyberman is to mistake the nature of Ascension and indeed resurrection. Cybermen are a hedge against death, qlippothic husks that believe in the body but not the spirit; there is no union of opposites here. And so they strive for Eternity rather than the Now, as if they could be those Eternals that the Doctor calls “empty nothings” back in Season 20’s Enlightenment. Anyways, the Ascension imagery here is pretty explicit – Danny and the Cybermen literally fly up into the sky to save the world through their self-sacrifice, which, as always, should be read as a metaphor for ego-death (thank you, Crimson Horror).

Another kind of “eye in the sky” image we get in Doctor Who is one that juxtaposes the Eye with a heavenly body. In The Rings of Akhaten, for example, we get an image of the Akhaten planet, which fancies itself a God, juxtaposed with the Doctor’s eye as we approach the great climax. Akhaten is a false god, of course. So is the Doctor. Notice that his attempt to kill the “god” fails. He fails because his strategy is borne not of ego-death, but out of a sense of self-aggrandizement, however self-loathing it may be (for self-loathing is still ultimately concerned with ego.) He thinks his life is “too big” for Akhaten to consume!

Another kind of “eye in the sky” image we get in Doctor Who is one that juxtaposes the Eye with a heavenly body. In The Rings of Akhaten, for example, we get an image of the Akhaten planet, which fancies itself a God, juxtaposed with the Doctor’s eye as we approach the great climax. Akhaten is a false god, of course. So is the Doctor. Notice that his attempt to kill the “god” fails. He fails because his strategy is borne not of ego-death, but out of a sense of self-aggrandizement, however self-loathing it may be (for self-loathing is still ultimately concerned with ego.) He thinks his life is “too big” for Akhaten to consume!

Conversely, Kill the Moon offers us a juxtaposition of the Moon with Clara’s eye. This is altogether stranger. I mean, Kill the Moon isn’t really about Clara’s ascension per se (though there’s certainly a kind of ascension involved by flying up to the moon and saving the Moon Dragon). Rather, this Eye Shot, which is part of the opening shot of the episode, ties into the final scene of the story where Clara stands by the window, pulls aside the veil, and looks at the moon; we see it reflected on the glass in the final image, juxtaposed with her face. This kind of juxtaposition strongly suggests that the Moon Dragon is a metaphor for Clara’s interiority, her identity, even. And it might very well be beyond words, so I will leave it as that.

Of course, Moffat didn’t create this kind of association; he’s one in a long line to play with it. In ancient times, the Eye in the Sky corresponded pretty simply to God, to an omniscient point of view. We still have its likeness on the US Dollar. But in terms of Doctor Who, and the specific juxtaposition of Eyes and Ascension, it’s really Russell T Davies we should look to. In Parting of the Ways, we get the dual ascensions of Rose and the Doctor, and those are rife with Eye imagery.

Rose is first. And, really, just by her very name (let alone her rose jacket) we should now recognize that she’s part and parcel of the season’s alchemy, a living embodiment of the rubedo stage of the Great Work. Now, when she looks into the heart of the TARDIS (which has access to every point and moment throughout Space and Time) her eyes blaze with golden light, and her words speak to an experience of glory:

Rose is first. And, really, just by her very name (let alone her rose jacket) we should now recognize that she’s part and parcel of the season’s alchemy, a living embodiment of the rubedo stage of the Great Work. Now, when she looks into the heart of the TARDIS (which has access to every point and moment throughout Space and Time) her eyes blaze with golden light, and her words speak to an experience of glory:

DOCTOR: What have you done?

ROSE: I looked into the TARDIS, and the TARDIS looked into me.

Which is almost a direct lift from Nietzsche: “He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster. And when you gaze long into an abyss the abyss also gazes into you.” Which is from Beyond Good and Evil, a phrase with a distinctly alchemical flavor.

ROSE: I am the Bad Wolf. I create myself. I take the words, I scatter them in time and space. A message to lead myself here.

“I create myself,” not just a moment of self-consciousness, but of self-realization. And she does so by creating a Bootstrap Paradox, for the words came to her before her Ascension, giving her the idea to send them through time and space to lead her back here, to her Ascension. There is no origin point, which is the point of the Bootstrap Paradox – it is an eternal loop with no beginning, no end, no cause, just pure being.

DOCTOR: Rose, you’ve got to stop this. You’ve got to stop this now. You’ve got the entire vortex running through your head. You’re going to burn.

The Doctor’s words are particularly poignant considering the Eye in the Sky imagery of Death in Heaven and The Big Bang, fiery eyes that are very much a source of burning. (In the Scottish vernacular, interestingly enough, the etymology of the name Burns is that of a “burn,” which is a brook or rivulet… a small River. I digress, but the alchemy of Fire+Water in that word is too juicy to pass up.)

ROSE: I want you safe. My Doctor. Protected from the false god.

EMPEROR: You cannot hurt me. I am immortal.

ROSE: You are tiny. I can see the whole of time and space. Every single atom of your existence, and I divide them. Everything must come to dust. All things. Everything dies. The Time War ends.

Again, she speaks of her union with all of time and space. She has the power to destroy any claim to immortality, and she does so with great prejudice. But notice what she says here – everything must die. All things. Including the Time War, which she ends by tricking the Doctor in Day of the Doctor to find another way; again she’s presented with glowing eyes.

DOCTOR: Rose, you’ve done it. Now stop. Just let go.

ROSE: How can I let go of this? I bring life.

And now she confers immortality upon Captain Jack. Which is particularly interesting as we prepare to discuss the implications of The Girl Who Died. It’s funny, by the way, that the Doctor chooses the phrase “let go” as he pleads with her. For to “let go” is actually what it takes to die. And, in a sense, to live. That ego-death, it’s all about letting go. Letting go of control. Grace doesn’t come without letting go.

DOCTOR: But this is wrong! You can’t control life and death.

ROSE: But I can. The sun and the moon, the day and night. But why do they hurt?

“Life and Death,” “Sun and Moon,” “Day and Night,” these are all positioned as a union of opposites. And again, with an acknowledgement of accessing Above and Below, Past and Future, in the Here and Now – explicitly as an act of vision:

ROSE: I can see everything. All that is, all that was, all that ever could be.

DOCTOR: That’s what I see, all the time.

“That’s what I see, all the time,” the Doctor says. And now the Doctor and Rose are mirrored.

When he kisses her, he triggers his own ascension. For he sacrifices his life to save hers. But because his perspective is fundamentally different from a human’s, so too is his ascension. His is not one of eternity or immortality, nothing so linear, no—his is of death and rebirth, something cyclical, circular. Like the iris of an eye.

Thank you, Mr Davies.

The Girl Who Died

So we have some interesting Eye symbolism to unpack in this episode. Right out of the gate, we get an extreme closeup of Clara’s eye. But this eye is upside down. It is reversed, an aspect of the mirror. The view gets longer and we then see both her eyes, and indeed her entire person, upside down, wearing that Red rubedo spacesuit, floating in space. I’m reminded of Amy floating in space at the beginning of The Beast Below, or better yet, Turlough in Enlightenment. This is a story about Ascension.

So we have some interesting Eye symbolism to unpack in this episode. Right out of the gate, we get an extreme closeup of Clara’s eye. But this eye is upside down. It is reversed, an aspect of the mirror. The view gets longer and we then see both her eyes, and indeed her entire person, upside down, wearing that Red rubedo spacesuit, floating in space. I’m reminded of Amy floating in space at the beginning of The Beast Below, or better yet, Turlough in Enlightenment. This is a story about Ascension.

But it’s not a “traditional” ascension story. The Eye presented upside-down promises some kind of inversion or subversion of the trope I’ve so painstakingly described. A false ascension, perhaps. Hmm.

This is kind of hinted at with the mirroring of the Doctor and “Odin.” Whoever Odin is, he’s not Odin. Not a god. Nor is the Doctor. It’s kind of delicious, though, that from both we get a similar kind of Eye imagery – for Odin wears an Eyepatch, and the Doctor’s sunglasses are cleaved in two, making each half look like an Eyepatch.

Odin, the real Odin, actual god of Norse mythology, he sacrificed an Eye to take a drink from Mimir’s Well, which bestows wisdom, a kind of remembrance given that Mimir is known as “The Rememberer.” But here the Eyepatch of “Odin” presents false images – the illusions of Ashildr, for example, and of course “Odin” presents a false face as well, a holographic image. Funny, that’s two episodes in a row where holography is invoked – and don’t forget, the Eye is also present as a striking closeup in Under the Lake/Before the Flood, with the writing that shines upon the cornea promising the false ascension of the Fisher King. False, because the “immortality” of those ghosts is an empty one, as people are reduced to electromagnetic signatures chanting over and over again the catchphrase of their cult: “Dark Sword, Forsaken Temple” (commas mine). The ghosts have no Eyes, only empty sockets.

Anyways, Odin’s eyepatch is mirrored in the construct of the Mire’s armor, which is rather Cyclopean in nature, one giant red eye presented through a slit (I’m reminded of old-school Cylons). Upon wearing one of these helmets, Ashildr is able to cast her own illusion, such that everyone believes in her dragon – which, we should point out, is based on one of her wood carvings (a “puppet”) and which was also subject to an extreme close-up of its eye. When Ashlidr wears the helmet, we see her bathed in Red light – the rubedo stage of the alchemical Great Work. Her death serves as a metaphor for an ego-death; naturally, this occurs while sitting in a Chair.

Ashildr’s first ascension, however, came early in the episode, when Clara put the Doctor’s “eyepatch” on her eye and had her focus on the word “open.” The two of them vanish in a puff of smoke and are raised on high to the Cloud in which Odin’s ship flies.

Ashildr’s first ascension, however, came early in the episode, when Clara put the Doctor’s “eyepatch” on her eye and had her focus on the word “open.” The two of them vanish in a puff of smoke and are raised on high to the Cloud in which Odin’s ship flies.

Likewise, Ashildr’s final “ascension” comes with a curious bit of “eye” imagery. The Doctor puts a talisman on her forehead, on her “third eye,” and this after a closeup of the device sitting in his palm. If the device itself is some kind of “third eye,” by association we now have a reiteration of the Hand Mine imagery from the season opener.

But this ascension is false. It is biological immortality, the path of a Qlippothic Cyberman.

It’s interesting, then, that Ashildr’s resurrection is show to us as “upside down,” as is that reflection of the Doctor in the water when he comes to realize what his “face” is supposed to mean, what he remembers from a previous life. And because these upside down figures (and that final shot of the stars circling Ashildr) mirrors that initial imagery of Clara, I do have to think that all this ties into Clara’s arc for the season as well. Especially given how the two “mirror shots” of The Magician’s Apprentice are Eye shots, one a reflection of Missy’s left eye in her compact mirror, the other a reflection of Clara’s face in the left eye of the Doctor’s sunglasses.

So consider the poignant final shot, circling round Ashildr as the cycles of the days and nights and seasons and stars spin around, casting an arc of infinity upon the sea, returning to her face, whereupon we begin to see the emotional cost of what the Doctor has done, and what her Ascension might mean.

It’s all in her eyes. We have only to look.

October 20, 2015 @ 5:28 am

So?

October 20, 2015 @ 5:34 am

Sorry! Wrong blog!

October 20, 2015 @ 9:47 am

I would add that the final scene, spinning around the newly-immortal Ashildr, draws attention to the power of eyes in a different way. It shows, dramatically, just how much acting is done with they eyes, and how much emotion is conveyed by subtle changes in facial expression around the eyes.

October 20, 2015 @ 9:57 am

Yes, it’s an amazing shot, and it’s nailed precisely because of the emotion conveyed through Ashildr’s eyes.

October 20, 2015 @ 10:32 am

So cool you choose this shot and this scene. And it was really interesting to read about mythology. I had a task about Odin for essay writing australia, but your explanation I like even more! Thank you for this post!

October 20, 2015 @ 4:00 pm

Given one season theme seems to be the importance of story-telling, overtly showing us the art of writing as they go, it’s the metaphorical, story mirror images that are leaping out at me this time, e.g.

in BTF he blows up a dam to make everything safe, in TGWD he starts a tiny ripple, which will become a dangerous tidal wave.

In UTL he needs promt cards to say ‘sorry for your loss,’ in TGWD he retreats with a shaken ‘i’m sorry, I’m really terribly sorry.’

in UTL/BTF he finds a way to save Clara without breaking the rules, in TGWD he breaks the rules to save one he doesn’t know.

October 20, 2015 @ 10:46 pm

So far: 1/2 Sewers, 3/4 dam, 5 lake/barrels

October 21, 2015 @ 7:57 am

I don’t feel erudite enough to respond more fully, but I really enjoy these observations and insights. More please. 🙂

October 22, 2015 @ 12:59 am

I love this so much, this article specifically, but this kind of dismantling in general. I hope this isn’t too much of a tangent, but if red lighting et al indicates a rubedo stage, and you also discussed color symbolism as albedo and nigredo which makes enough sense to me in relation to the alchemy, what would blue or green light or coloring refer to? Do they have a stage in this, or some relation? Or does that break out to different symbolism? Where can I learn this stuff??!? I’se gots to know now!

October 22, 2015 @ 10:33 am

Hi Jeremy,

I think it’s important to note that such color symbolism as I note isn’t “inherent” to the colors themselves, but is contextual to the text. Black/White/Red, for example, can have a lot of different meanings, the alchemical progression being just one of them.

And of course color symbolism can work on multiple levels. Amy Pond’s color, for example, was definitely Red, while Rory’s tended to be Green… but RTD often reserved Green for monsters and the monstrous. Rose Tyler, of course, Red. River’s palette was predominately gold. In the Clara era, on the other hand, Yellow is often used as a marker of Death, kind of like Orange in the Godfather movies.

Throughout the Revival, we often see a juxtaposition of Red and Blue, in which case it’s functioning as a Union of Opposites, like Fire and Water, respectively: Rory’s new car is Red, parked out front of a Blue door to their new home, or Melody’s bright red corvette swerving up to the TARDIS. I found it particularly interesting when Eleven opted for a Purple coat, a literal union of red and blue. In the Davies era, a Blue time-tunnel was for traveling back in the past, while Red was traveling into the future.

And of course the TARDIS is blue, making this a Doctorly color. Look at Rose and you’ll see the Doctor framed in Blue light (a halo, at that) when he stands in front of that magnificent ferris wheel… called The London Eye. 🙂 I tend to think Blue is used for something outside the Alchemical spectrum, an incursion or breach of the Divine that’s beyond the Great Work of us mere mortals. 😉

Anyways, because the symbolism of color is context-dependent, it’s something we just have to pay attention to, see what contexts the colors are used in, and over time we can determine how to “code” their usage. So, going back to Series One, we get Gold used in a particular way in The Doctor Dances (healing nanogenes) and Boom Town (Heart of the TARDIS) and that in turn informs how Rose’s ascension in Parting of the Ways comes off. And even if we’re not paying attention, I do think it registers at the subconscious level, which is one of the reasons why that scene is so effective.

In short, careful observation is the only key to true and complete awareness.