The Punishment of Luxury: Revisiting Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark in 2017

Longtime readers will know it’s been a very long time since I had anything at all to say about pop music. Newer readers will probably not know that I ever did in the first place: In my late high school years and into college I started to get really into contemporary music, as, I suppose, you do at that age. I used to say music was the art form that touched me more than any other, and when I first started my writing career (or what passes for it) I spent a lot of time trying to write about music and used to do an end-of-year recap of what I thought were the best and most important releases for me personally of the past year. I stopped doing that in 2013 (incidentally the last year the band du jour released something), I don’t say anything that dramatic anymore and I thought I was kind of done with pop music after that: Almost all of my listening these days is done on Soundcloud and I couldn’t hope to be considered any kind of an authority for what’s out there now, nor, really, should I be (though I am known to get vocal when I find something new I do get into).

Longtime readers will know it’s been a very long time since I had anything at all to say about pop music. Newer readers will probably not know that I ever did in the first place: In my late high school years and into college I started to get really into contemporary music, as, I suppose, you do at that age. I used to say music was the art form that touched me more than any other, and when I first started my writing career (or what passes for it) I spent a lot of time trying to write about music and used to do an end-of-year recap of what I thought were the best and most important releases for me personally of the past year. I stopped doing that in 2013 (incidentally the last year the band du jour released something), I don’t say anything that dramatic anymore and I thought I was kind of done with pop music after that: Almost all of my listening these days is done on Soundcloud and I couldn’t hope to be considered any kind of an authority for what’s out there now, nor, really, should I be (though I am known to get vocal when I find something new I do get into).

I feel, I hasten to add, that this remains true and I’m still not. However, when my favourite band suddenly re-emerges out of seeming retirement after four years to release an album in 2017 entitled The Punishment of Luxury, I’m kind of obligated to sit up and take notice.

There is no pop/rock outfit that has had a bigger or more profound effect on clarifying my musical and aesthetic sensibilities than Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark. There have been times I’ve tried to deny this or talk myself out of admitting it, but it’s never not been true. 1980s synthpop, and its stylistic Top 40 descendants, was the soundtrack to the most formative period of my life. Not OMD per se, but bands that sounded a lot like (and probably in hindsight owed a great deal to) OMD. And not just in the 1980s heyday, but well into the 1990s and 2000s given the slow trickle with which pop culture made its way to the hills and mountains where I’ve spent most of my life (it is not an exaggeration to say we’re 20 years behind everyone else).

As soon as I knew enough to keep track of different bands, genres and albums, I went back and listened to radio stations that played music exclusively from the 1980s to try and hunt down and rediscover the music that had been so important and meaningful to me so long ago. And when I did that, one name kept coming up over and over again: Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark. Here was a band who made music that sounded just like the way I remembered, and their songs always seemed to stand out from the crowd in terms of craft and quality. I’d be singing them to myself long after I’d forgotten everything else I heard the night before. Plus, they had one hell of a distinctive and evocative name.

As I was soon to learn, Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark did not start out as what we’d consider a normal “pop” band. Andy McCluskey and Paul Humphreys met in the mid 1970s while each was bouncing around the Merseyside-Liverpool area trying to get other musical experiments going, and bonded over their love of Kraftwerk and bizarre, electronic soundscapes they would bang together out of the likes of tape machines, old radios and the cheapest synthesizers they could get their hands on. And yet despite their Kraftwerkian, musique concrète origins and off-kilter lyrical influences (like energy usage, red telephone boxes, oil refineries, shortwave radio transmissions and Vorticism), OMD have an almost preternaturally innate knack for melody and pop songwriting structure, resulting in amazing should-not-have-beens like chart-topping love songs to Joan of Arc (one after another…and both of which have the same title) and club anthems condemning the atomic bombing of Japan.

OMD blend an extremely academic fascination with technology and Western society’s relationship to it (seriously, there is absolutely no better band for a wide-eyed, prospective student of Science and Technology Studies/Social Studies of Knowledge to become obsessed with) with a raucous, to-the-point working-class everyman sensibility and sense of romance, loyalty, melancholy and righteousness. As, one might perhaps expect, befitting a band born from the streets of Liverpool, where the pullout of local industry and manufacturing left an entire region hanging out to dry with no sense of a material future. This doubly resonated with me as at the time I was living and working in the capital region of New York, one of altogether too many communities of the United States that shared a similar fate to the North of England.

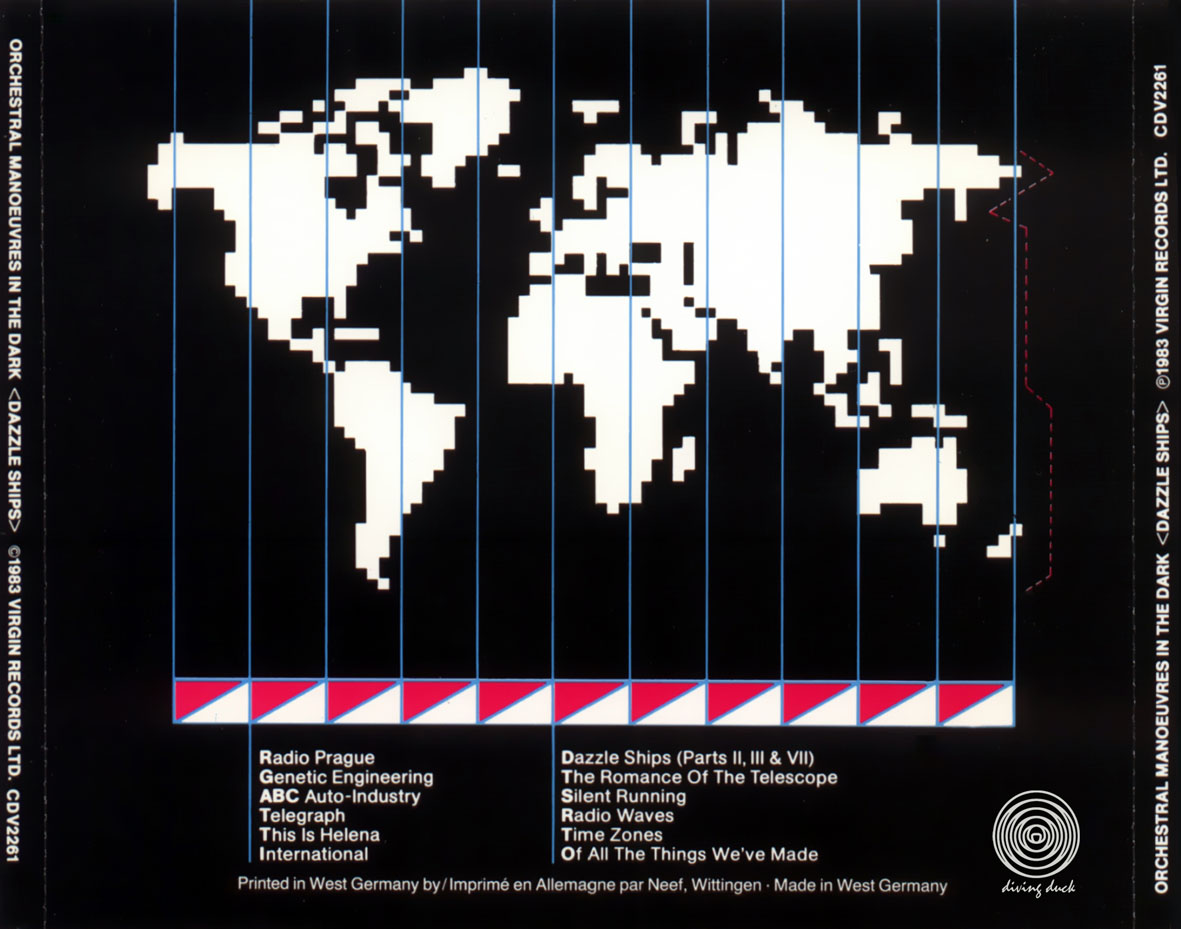

The forgotten postindustrial urban ruins living in the shadow of the upwardly mobile neon canyonlands that Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark sing paeans to defines my understanding of city life (bonus points: Try and connect my interest in this aesthetic with the Miami of the 1980s that Michael Mann depicted in Miami Vice, or to the bubble-era Tokyo of Godzilla 1984). And while the towering and revelatory  Architecture & Morality is usually considered to be OMD’s masterpiece, for my money, nowhere do they make that point clearer or more haunting than on their 1983 album Dazzle Ships, a beguiling masterpiece of confusion made up of sound collages of radio samples and Speak-and-Spells alongside morose pop songs inspired by late Cold War postmodern malaise. It’s all wrapped up in a gray and wintry aesthetic package inspired by World War I iconography, global telecommunication and modernist art movements, and capped off with the breathtakingly stratospheric lead single titled, of all things “Genetic Engineering”, as unforgettable and searing a piece of music as I’ve ever heard. Dazzle Ships easily became my favourite pop music album Of All Time once I finally “got” it, and it stayed that way for years and years until 2014 when it was finally dethroned by Trust’s Joyland, which is basically what OMD would sound like if, instead of growing up in the deindustrialized English North, they somehow emerged Elf-like from deep within the Boreal Forests of Canada.

Architecture & Morality is usually considered to be OMD’s masterpiece, for my money, nowhere do they make that point clearer or more haunting than on their 1983 album Dazzle Ships, a beguiling masterpiece of confusion made up of sound collages of radio samples and Speak-and-Spells alongside morose pop songs inspired by late Cold War postmodern malaise. It’s all wrapped up in a gray and wintry aesthetic package inspired by World War I iconography, global telecommunication and modernist art movements, and capped off with the breathtakingly stratospheric lead single titled, of all things “Genetic Engineering”, as unforgettable and searing a piece of music as I’ve ever heard. Dazzle Ships easily became my favourite pop music album Of All Time once I finally “got” it, and it stayed that way for years and years until 2014 when it was finally dethroned by Trust’s Joyland, which is basically what OMD would sound like if, instead of growing up in the deindustrialized English North, they somehow emerged Elf-like from deep within the Boreal Forests of Canada.

It’s not always been easy being a fan of Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark. I hope you out there reading have had it better, but my experience of attempting to get seriously into pop music involved a lot of stolid old music critics (and music snobs) telling me in no uncertain terms that there were distinct rules about what was cool and musically worthwhile and what wasn’t, and there were very clear directions about what I was supposed to like and take seriously and what I wasn’t. Hard rock and heavy metal? No problem. Nobody questions you if you put on Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath or Iron Maiden. Same goes for any kind of alternative rock, folk, punk (emo or otherwise), or “acceptable” pop music, like The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. Synthpop, or really anything involving any kind of 80s electronic sound (sometimes even extending to anything melodic)? Absolutely not. You let slip you like keyboard music or 80s pop of any kind, and you are immediately marked as tasteless and tin-eared and made fun of mercilessly (ironic as it is considering a great deal of OMD’s output could safely be called “alternative pop” or “alternative dance” today).

I had people laugh at the admittedly rather daft name “Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark” (a band class trying to navigate a forest at night is one particularly noteworthy put down I remember) or make fun of me for liking an album called Dazzle Ships (without even listening to it) by saying that it sounds like a name that should be delivered with “Jazz hands” (it’s named after the intersection of WWI naval camouflage and modern art as a metaphor for Western culture, philistines). Not to mention any and all of the music critics I read that refused to give 80s synthpop the time of day when it came to serious historical and cultural analysis. So I kept my love to myself, at times honestly ashamed that I liked this kind of music as much as I did, forcing myself to try and like other music instead (do not ask me about my metal phase. Or really, my Iron Maiden phase). All the while even as the other half of me kept stressing that there was a perfectly defensible reading of albums like Architecture & Morality and Dazzle Ships showing they had real artistic merit, even with the hooks, melodies and synthesizers.

Sadly, Dazzle Ships was a commercial failure upon release (though it’s proven to be a huge musical influence in the years since: Radiohead cribs more than a fair bit from it, just to name one particularly egregious example), which spooked OMD into spending the rest of the 1980s making inoffensive bubblegum pop electronica for the Top 40 set, most famously the inescapable “If You Leave”, written for the soundtrack to the John Hughes movie Pretty in Pink. It’s a good single, arguably a classic one, but it’s also a single tailor-made for (and found in) every high school prom ever and remains to this day an overwhelmingly overplayed stalwart of the kind of terrestrial radio that seems to only play the same 10 iconic popular hits over and over again in constant rotation.“If You Leave” used to be a sentimental favourite of mine, but now I can’t fucking stand the bloody thing, and when I turned on it I turned on it swift and hard. “If You Leave”, and what it did to OMD, is a big part of the reason I kind of hold a grudge against the whole John Hughes thing and the cultural impact those films had on the 1980s and those of us who choose to remember them.

But even during this era, which can only be called their decline period, OMD’s professionalism of craft and knack for melody allowed them to regularly and reliably turn out cracking synthpop numbers easily above and beyond those of their peers: Check out “Tesla Girls” (which still manages to retain a bit of that bonkers early OMD sensibility), “Secret” (dig Andy McCluskey’s gloriously out-of-place Sonny Crockett inspired getup in the music video for that one) and the utter barnstormer that is “Dreaming”, none of which you should be at all ashamed about enjoying completely unironically. Even OMD defenders can roll their eyes at this stuff, but that’s displaying the exact kind of snobby rockism I was denouncing above. Out of all OMD’s songs (“If You Leave” notwithstanding), these are the ones you’re most likely to hear on the radio or on an 80s playlist, and indeed, they were the ones that got me into the band in the first place. But it’s not just my own personal nostalgia that makes these singles deserving of your attention and respect: They’re not going to win any awards for songwriting, but these are legitimately great pop songs with a pleasing sense of manufactured adolescent earnestness, and “Dreaming” in particular I’d go so far as to call absolutely perfect.

Andy McCluskey carried on solo using the Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark name throughout the 1990s, a sidenote to the band’s career that produced (in my not so humble opinion) exactly one noteworthy song (“Pandora’s Box”, a tribute to silent film starlet Louise Brooks, though it’s better when they play it live today with Paul Humphreys backing Andy up), before putting OMD on ice to spearhead the Atomic Kitten girl group project. The band proper wouldn’t return until 2006, an event which saw a slew of remasters of OMD’s classic albums, and a brand new release: The first record featuring exclusively the “classic” lineup from the 1980s of McCluskey, Humphreys and their friends Malcolm Holmes and Martin Cooper since Dazzle Ships. The result was History of Modern, an album I was super psyched for all throughout 2009 (I mean come on, that title)…Up until its release in 2010, when it became evident that it was actually kind of bad.

History of Modern felt like OMD pastiching themselves, running down their musical influences while mixing in a bunch of dusted-up unused song concepts from the 80s. This is not necessarily a terrible idea: OMD have done this multiple times in the past-Dazzle Ships is basically half unused concepts culled from the recording sessions for Architecture & Morality, and so is “Dreaming”-but this time it didn’t quite seem work out for them. There were some standout tracks here, namely the fabled OMD Holy Grail of “Sister Marie Says”, which finally saw a proper release (that song was the intended A-side to a single planned for 1988 that never came about. The intended B-side? “Dreaming”). But an alarming number of songs on this album I frankly found tough to even physically listen to, with combinations of poorly-thought out lyrical motifs and song styles that made me distinctly uncomfortable. Even the band themselves seem at times somewhat regretful of this effort, with both Andy and Paul emphasizing that they felt the record was overproduced.

OMD released a follow-up in 2013 in the form of English Electric, with a more stripped-down electronic sound and more cohesive sense of aesthetics and themes. It’s that quintessential OMD melancholia about mankind’s relationship with technology, this time in the form of futures we dreamed about when we were children that never came to pass: Namely, the broken promises of mid-20th Century modernism. I thought English Electric was very good, and it had a killer lead single in the form of “Metroland”, but I did feel there were some places here and there where it came across as less of a new beginning and more of a better version of History of Modern: A second draft that still runs down OMD’s influences, self-pastiches and retooled old ideas, but wraps them up in a package that’s more artistically defensible and coherent (even on “Metroland”, which really wears its Kraftwerk influence on its sleeve. I mean, we’re pretty much straight Trans-Europe Express all up in here). Though they claimed to be creatively re-energized by it, the English Electric era was also apparently “grueling” for the band, and that shows in the final product. With an album so downbeat and introspective, and with a closer worryingly entitled “Final Song”, I got the implicit sense English Electric was going to be Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark’s epitaph to itself: An attempt to sum up everything it had been and wanted to be and putting it out as one final definitive statement.

OMD released a follow-up in 2013 in the form of English Electric, with a more stripped-down electronic sound and more cohesive sense of aesthetics and themes. It’s that quintessential OMD melancholia about mankind’s relationship with technology, this time in the form of futures we dreamed about when we were children that never came to pass: Namely, the broken promises of mid-20th Century modernism. I thought English Electric was very good, and it had a killer lead single in the form of “Metroland”, but I did feel there were some places here and there where it came across as less of a new beginning and more of a better version of History of Modern: A second draft that still runs down OMD’s influences, self-pastiches and retooled old ideas, but wraps them up in a package that’s more artistically defensible and coherent (even on “Metroland”, which really wears its Kraftwerk influence on its sleeve. I mean, we’re pretty much straight Trans-Europe Express all up in here). Though they claimed to be creatively re-energized by it, the English Electric era was also apparently “grueling” for the band, and that shows in the final product. With an album so downbeat and introspective, and with a closer worryingly entitled “Final Song”, I got the implicit sense English Electric was going to be Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark’s epitaph to itself: An attempt to sum up everything it had been and wanted to be and putting it out as one final definitive statement.

So imagine my surprise when, in early 2017, OMD released a new single. And announced a forthcoming new record…called The Punishment of Luxury.

This essay is getting very out of hand, so I’m breaking it into parts. Come back next week where I, hopefully, take you through The Punishment of Luxury cover to cover and track-by-track.

November 1, 2017 @ 10:41 am

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qzuXlKU6eCw