The_OA Exegesis: Champion

Thank you for coming back. My travels have kept me away. I’m so sorry to have kept you waiting.

Thank you for coming back. My travels have kept me away. I’m so sorry to have kept you waiting.

You must be hungry! Aren’t you? Maybe having a little bite of something something will help to take the edge off. Yeah, a nice morsel. A small good thing. Maybe a chicken sandwich, or a bowl of soup. Maybe some chocolate, or chips. Something charred, perhaps? Or a bit salty? Maybe something cheesy, or with tomatoes, something with color.

Whatever it is, go get it now. That tasty thing.

I’ll wait. Oh, and save one bite for the end, if you would.

Thank you. You know who you are.

Champion

Again, the opening image of the episode points to something significant in its middle, something significant that ends up being a point of failure. In “New Colossus” we first saw the eyes of the Statue of Liberty, and that place marked a huge turning point in Prairie’s life, but it wasn’t exactly a success for her. This is where her prophecy failed her – but then, maybe she was always going to be found by Hap, and she simply ended up being the cause of her own fate. In any case, there’s a profound irony between the Statue of Liberty, and how “New Colossus” ends with the revelation of Prairie’s imprisonment. Here, we get another seeming success: Prairie actually finding Homer’s ring, and a cell phone bill, which allows the prisoners a chance at escape—only for it to completely fall apart when the ring is ultimately lost. Clever manipulation fails, and the episode ends with images of brute strength and violence.

That said, we really should attend to the implications of everything to do with Homer’s ring, especially in light of the repeating motifs that have already been established in the first two chapters. First, we’ve detailed a number of circular motifs—Homer’s ring was actually mentioned in “Homecoming,” and in “New Colossus” we got details like The Healos’ “Full Circle” with its verses pointing towards Ouroboros (combined with various snake references) and hence Eternal Return. As we established in Chapter 1, the presence of WATER symbolizes a “bridge” in The_OA, a passage between different realities, a way to cross from the Ordinary World to the Other Side. And as we saw in Chapter 2, the presence of GLASS symbolizes separation and isolation. All these signifiers come together in the championship ring scenes.

Homer’s ring returns, again and again—in the opening image, which itself is presented as being underwater; then when Prairie finds the ring and drops it in a bathtub that holds a woman long dead (of course); and finally when the ring is passed back and forth between the glass cubicle prisons via an underground river, a river that eventually captures the ring (enveloped in a wireless cell phone bill) and takes it away forever. So, yeah, there’s plenty here to work with. The ring symbolizes eternity—the snake eating its own tail, the perpetual cycle of death and rebirth. Of course it’s going to get back to Homer via the river, which is that bridge that can penetrate the glass walls of separation, which also indicates that the individual cells of Prairie, Homer, Rachel, and Scott might be different realities unto themselves, a nice metaphor for the human condition. Of course the river takes the message of Eternity to a watery grave. It’s… it’s neat, I think, to suggest that we ultimately have to let go of our notions of Eternity. That a hope for perpetuity in the endless cycle of death and rebirth is something to escape from rather than to clutch onto.

There’s an extra layer here to consider as well—in Chapter 2, the use of the SNAKE motif, with the opening shot of snakes tucked away into glass cubicles, suggests that the prisoners are snakes themselves, symbolically at least. So the source of Eternity, of that endless cycle of shedding your skin, is something that actually comes from within, not without. It’s tapping into that power that ultimately allows Prairie, Homer, Scott and Rachel to connect. Their plan for escape fails, but the walls that separate them have started to come down, figuratively speaking, they’re able to work together in a way that they hadn’t been able to before. They’ve become connected, which itself is a form of resistance against Hap’s domination.

Glass Houses

OA: The first time you fall asleep in prison, you forget. You wake up a free woman. And then you remember that you’re not. You lose your freedom many times before you finally believe it.

One of our concerns here at the Exegesis has to do with the practical application of alchemy to our real world concerns, which is one of the things we really appreciate about The_OA. This show isn’t just about one woman’s journey through death and back again, but about the nature of fear, and power, and how we can respond to it, and how effective those responses may or may not be. It does this primarily through metaphor—I mean, it’s not like we’re all locked away in the basements of mad scientists, literally speaking. But this is such a fantastic and striking image that we can glean general structural principles to the dynamics of power-over that can be applied to a variety of real-world situations.

So what is it that actually imprisons us? Not literal walls of glass, no. Not our computer screens, really. But “walls of glass” certainly makes a nice image to represent the prison of a mind that isn’t aware of the restrictions it places upon itself in response to the abstract structures of power and domination. Take, for example, how differently we behave when we believe we’re being observed versus when we think we have privacy. On the one hand, such… viewability… can be incredibly constricting. We see this when Prairie and Homer pass the ring back and forth only while Hap is outside burying the body of August. They couldn’t do this when they thought they’d be seen. It’s much the same as we saw in Chapter 1, when Nancy and Abel remove the door to their daughter’s bedroom, to keep her under surveillance.

And yet, conversely, open doors are also what we need to let someone in to our lives, to forge a real and deep connection. To be seen by another, we must be visible, open. So it’s not visibility itself that’s inherently oppressive. How visibility functions depends on the context of the existing power structures and intentions that are already in play.

So when Hap is down in the basement wiping WATER off the windows (preventing connection in the midst of isolation), loudly, in the dark before daybreak with only the light of his headlamp to guide him (the light emerges from his forehead, the “third eye,” indicating his focus is actually on something that resides deep with human consciousness, as well as what his impact really is), we see things like Homer rolling over and ignoring him, and Prairie waking up restlessly to the noise, and Scott hiding behind one of his plants, like a feral animal in the jungle. Hap is exercising material control over his prisoners, from their perceptions of day and night to the food they eat, so their visibility is another form of constriction.

But then Prairie stands up for herself, uses that visibility to reach out to Hap and manipulate his emotions: she’s blind, she needs fresh air and sunlight so as not to lose her mind. And Hap complies. She uses the opportunity of visibility to make herself seen as she wants to be seen—which isn’t necessarily the same as being seen for who she really is, which is much more powerful, but not always appropriate when power relations aren’t balanced. Nonetheless, she’s actively resisting her conditions. And when the time comes for her to bond with Homer, Scott, and Rachel, the visibility of each other makes that possible… because they’ve finally been able to exercise power with each other, which is rooted in having the same power amongst each other. This is something that exists even though Prairie has privileges not afforded to the others. It exists because despite those privileges, she doesn’t use them to establish herself within a hierarchy. Given the opportunity to eat real food, for example, she waits until she can bring sandwiches to everyone.

However, the glass prison isn’t so easily dismantled.

OA: We were like the living dead. Right next to each other, but alone. There’s nothing more isolating than not being able to feel time.

“The living dead,” what a great line. It evokes the sense of being in a coma—what Homer recovered from back when we saw his “news story” on YouTube in Chapter One, and what Hap described the ordinary world as back in Chapter Two. We are zombies, asleep, not woke, only milling about looking for something to eat. At least, that’s how we are before some kind of enlightenment to the situation we’re actually in.

And even if we’re “awake,” that doesn’t mean we’re free. As OA pointed out, when you’re in prison you have the illusion of being free, and then one remembers that one is not as you wake up. Waking up doesn’t change power dynamics,  it only informs us to power dynamics that we weren’t previously aware of. And just being aware doesn’t solve our problems for us.

it only informs us to power dynamics that we weren’t previously aware of. And just being aware doesn’t solve our problems for us.

Take, for example, the scene where OA and Steve huddle in an empty bathtub. It’s an interesting scene, starting with the fact that it takes place in an empty bathtub, with OA staring out a window as a single lit tree. Bathtubs are containers for water, the “bridge” in this show, so an empty one is striking both visually and thematically. There’s the suggestion of connectivity between OA and Steve—they’re getting into casual conversations that don’t really have a point to them other than self-expression and getting to know each other. Like, OA starts waxing philosophical, talking about the family that was going to live here and what life was going to be like for them: fights in the kitchen, making babies, heartache, sex, growing old.

STEVE: You sound like one of the poetry kids.

OA: Poetry kids?

STEVE: You know, the ones who write poems about, like, cutting themselves and shit.

Like OA wouldn’t have any idea about cutting herself or anything. Anyways, while she’s telling this story, she starts laying out little pieces of tile on the edge of the tub, arranging them like little walls, forming little parallel compartments. I’m sure there’s a metaphor here, maybe for parallel realities? Like, the Abandoned House in this reality is, well, abandoned, but had the economy not collapsed then the there’d be a family living here instead. Something like that. Or perhaps the realities are nested, like Russian Matryoshka dolls, or the concentric rings that flash on the screen at the end of this chapter.

Steve asks about whether OA’s plans include something “dangerous,” namely the rescue of Scott and Homer and Rachel. She nods, and then Steve reaches out to touch her hair. OA reacts—she’d said back in the first episode that “no touch” was one of the rules, and here Steve has just broken it. This ends their reverie, and she leaves the house. Which demonstrates that even though OA is now free from the imprisoned reality that she’s described to the Five, the internal prison remains, she’s not free enough to let herself be touched by another human being yet. She still flinches from touch, having been denied it for so long.

Steve asks about whether OA’s plans include something “dangerous,” namely the rescue of Scott and Homer and Rachel. She nods, and then Steve reaches out to touch her hair. OA reacts—she’d said back in the first episode that “no touch” was one of the rules, and here Steve has just broken it. This ends their reverie, and she leaves the house. Which demonstrates that even though OA is now free from the imprisoned reality that she’s described to the Five, the internal prison remains, she’s not free enough to let herself be touched by another human being yet. She still flinches from touch, having been denied it for so long.

I bring all this up because I don’t want us to lose track of this underlying current. The glass prison, the translucent prison, it doesn’t need physical glass to function effectively. This is because it’s so pervasive in society, it’s become an assumption that everyone takes for granted.

As soon as OA leaves the house, we get Alfonso “French” Sosa coming back in, and an altercation between him and Steve ensues. This starts, however, with an invocation of power dynamics:

FRENCH: Hey, what’d you do to her?

STEVE: Nothing. Don’t treat me like I’m some fucking pedophile or something.

FRENCH: Pedophiles are people who are into kids.

STEVE: You think you’re so fucking smart, don’t you? You think you’re the king of the world and we’re your dumb little servants?

French, as we noted previously, is someone who has complied with the system, whereas Steve has reacted with rebellion. The system, though, as Steve astutely points out, is one based on the notion of kings and servants, of an established power relationship that’s based on overt domination. But this isn’t ultimately what presses Steve’s buttons—it isn’t until French brings up the fact that Steve’s parents want to send their son to military school in Asheville, invoking another context of domination and more importantly one of abandonment that Steve and French actually resort to violence against each other. And it’s funny, Steve is all sure that he can still beat up French (having done so, apparently, when they were twelve years old), and actually gets in a nice cut on French’s forehead, but French quickly established his own dominance and gets Steve on his back in a chokehold. When French relents, Steve calls him a “pussy” because he didn’t go all the way, but it’s not like Steve tries to reassert himself after this.

This is all still glass prison stuff. By establishing hierarchies, true connection is prevented.

Systems of domination are so pervasive that they even infiltrate our leisure activities, our games. Like football (American style). Or lacrosse. We haven’t talked about football yet, other than as an example of school-related violence, but this is a thread that’s been present for three chapters now. In Chapter One, Homer’s near-death experience happened on a football field, and the sidebar to this YouTube video had other football-related activities highlighted. In Chapter Two, we noted that a news story in the background of French’s mother’s room was in the context of a local college’s football game, and of course French got his scholarship in part because of his sports activities. In Chapter Three, it all starts to converge: we see Homer in his varsity jacket and we find he’s now got a proper championship ring; French blames the wound he got on his forehead from Steve on lacrosse; and then there’s this strange shot of a football field that sticks out like a sore thumb, because it’s not like any scenes prior or hence actually take place anywhere near a football field.

Systems of domination are so pervasive that they even infiltrate our leisure activities, our games. Like football (American style). Or lacrosse. We haven’t talked about football yet, other than as an example of school-related violence, but this is a thread that’s been present for three chapters now. In Chapter One, Homer’s near-death experience happened on a football field, and the sidebar to this YouTube video had other football-related activities highlighted. In Chapter Two, we noted that a news story in the background of French’s mother’s room was in the context of a local college’s football game, and of course French got his scholarship in part because of his sports activities. In Chapter Three, it all starts to converge: we see Homer in his varsity jacket and we find he’s now got a proper championship ring; French blames the wound he got on his forehead from Steve on lacrosse; and then there’s this strange shot of a football field that sticks out like a sore thumb, because it’s not like any scenes prior or hence actually take place anywhere near a football field.

So let’s talk about football and lacrosse for a bit. Lacrosse was actually a Canadian aboriginal ritual discovered by the French when they entered that territory – they called it “lacrosse” after the long sticks with curved nets on the end that are the standard equipment used in the game we also call “field hockey.” Well, actually, let’s call it ritual – for the originators, it was most definitely ritual, specifically symbolic of warfare but presented as an offering to the Creator. American football is also laden with war metaphors – there’s attack and defense, “aerial assaults” in the passing game (a deep pass is called a “bomb”), and there are “smashmouth” running plays, plays that are run “up the gut” and down someone’s throat. There’s actually a rape subtext here too, as “scoring” means either getting into the “end” zone, or “splitting the uprights” with a kicked field goal.

Regardless, the whole point of these games, or rituals, as practiced today is for one side to establish and demonstrate dominance over the other. And nowadays, games aren’t played to a tie; there must be a victor. And, eventually, a “champion.” “Champion,” by the way, is the title of this chapter. The word means not just someone who is victorious over another, who wins in a game of power-over, but also refers to fighters in general, especially those who fight on the behalf of others (this has shades of French’s scholarship from the Knightsmen Foundation). But the word “champion” actually derives from the word “campus,” which we now associate with, well, schools. Schools have campuses; this is where they are located.

Funnily enough, though, the word “campus” originally referred to a “field of battle.”

So let’s wrap our dive into the local school system with Steve’s foray into “alternative school” in the bowels of the school, a dead end where the word “physics” (not “psychics”) is painted on the walls such as to take advantage of the optics of a particular perspective. Now, “alternative school” is basically sitting in front of a computer while a condescending woman tells you to go at your own pace. Again, even here, there’s an aspect of power-over. Condescension only happens when a power imbalance is recognized, and actually when it’s being reinforced.

So let’s wrap our dive into the local school system with Steve’s foray into “alternative school” in the bowels of the school, a dead end where the word “physics” (not “psychics”) is painted on the walls such as to take advantage of the optics of a particular perspective. Now, “alternative school” is basically sitting in front of a computer while a condescending woman tells you to go at your own pace. Again, even here, there’s an aspect of power-over. Condescension only happens when a power imbalance is recognized, and actually when it’s being reinforced.

The layout of the room itself enforces a lack of connection amongst the students: they are all sitting behind computer screens (glass walls, in other words) and as such they can’t really see each other. You’d have to lean around the screen to see who’s sitting across from you. Like one student does with the woman sitting next to Steve. She immediately recognizes that the young man is looking at her tits, and she makes a big scene—she takes Steve’s water, pours it over her breasts, then throws the empty bottle at the, um, jeez he’s not really a teacher, is he? More like a monitor. Another pair of eyes in the Panopticon. (Given that Steve actually points out that the water is his, and given that water is a “bridge” or a medium of connectivity in the visual language of the show, we’d expect Steve and the young woman to eventually develop a relationship, right?)

She goes unnamed in this chapter, alas, but we’ll address her name later. It’s terribly apt. But what we can do is see how she is reacting to power structures—like the male gaze, or the “alternative school” overall. She is a rebel, like Steve. She reacts with big gestures and the intimation of violence. Quite natural. Also pretty ineffective in the long run, as power-over structures have already cornered the market when it comes to violent expression. (But damn, pretty satisfying in the short term!)

A Lamb in Wolf’s Clothing

A Lamb in Wolf’s Clothing

The young woman has put together an interesting ensemble for herself. I was particularly taken with her jewelry – she wears necklaces featuring both an Ankh and a Yin-Yang symbol. Now, this isn’t out of the ordinary for someone rocking a light-goth look. Entirely apropos. But I still think it’s a neat production choice – the Yin-Yang points back to our basic alchemical principle, the union of opposites, while the Ankh means “life,” pure and simple, though it often carries divine connotations; it’s also been hypothesized that it represents the union of the “male triad” and the “female unit.”

Anyways, it’s here that we’re going to start paying closer attention to things like costuming in The_OA, for it’s here that we see OA actually pick out an item of clothing to wear while shopping with her mother. She picks out a sweatshirt with a Wolf printed on the front, which is a stark contrast to her outfit in flashback, where she wears an overshirt that resembles lamb’s wool. And, I dunno, I think there’s something to be said about this. Back when she was Prairie, she really did have the innocence of a lamb. Now, she’s The OA, and there’s a darker connotation to this… she is no longer a lamb, but looking to feast. Which suggests a lot more intentionality to her storytelling with the Five than might be readily apparent. She really is a completely different person with them than she is with, say, her parents.

The color of the Wolf shirt is a kind of purplish periwinkle. Now, this doesn’t have a particular Alchemical resonance in of itself. (The colors of Alchemy are traditionally Black, for the nigredo period of self-disintegration, White or Silver, for the albedo period of self-purification, and Yellow to Red for the rubedo period of integration and spiritual mastery, all three of which make up the Great Work. So when Rachel tells the story of her near-death experience, which for her includes an out-of-body experience at the scene of her death, and points out that her little brother had a RED backpack from this out-of-body perspective, it’s a story that has a particular alchemical resonance.) However, just because a color isn’t alchemical doesn’t mean it can’t have resonance of its own within the text itself. And as it turns out, there is an interesting color palette at work within The_OA.

In particular, we see a kind of lavender hue associated with Hap. The lights above the glass cages at dusk, for example, have a faint purplish glow. The bath water in which the dead body of August sits has that same color to it. It’s the same color of Hap’s scarf when he finds Prairie in the New York subway. It’s the same color, actually, that gets added to blue to make it periwinkle.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves—we aren’t supposed to know yet what Hap and The OA are actually up to at this point, so let us just leave these fashion choices here for posterity and attend to one last costuming detail before the intermission: Betty Broderick-Allen’s broach. It’s a lovely bird motif, all shiny and sparkly! I like sparkles. Anyways, this cues us into BBA’s path in the show – she is becoming a bird (and don’t forget, when we first saw her in Chapter One, we saw her with a veritable flock of tweety-birds pasted to the chalkboard behind her). Birds are symbols of freedom, we think, for this show at least. BBA is slowly earning her freedom… but we’ll get to her after the break.

Intermission

Intermission

Today we have a couple of songs sung by Sharon Van Etten. Van Etten plays Rachel on The_OA, but acting is a relatively new gig for her, as she’s an accomplished singer and songwriter in her own right. In Chapter Three, we get to hear Van Etten sing a couple of songs, one as Rachel, and the other as a voice over at the end of the episode.

The first song is one of Van Etten’s own compositions, “I Wish I Knew,” from her debut album Because I Was in Love. It’s a striking scene—Rachel has just told the story of stealing away her little brother to pursue her dream as a singer in Nashville, but she flipped the minivan and had her NDE, and in the process left her brother in a wheelchair. Anyways, Rachel starts imagining what she’d do if she escaped Hap’s prison, and she says she’d sing a song to her little brother. Homer eventually asks Rachel to sing the song, at which point she turns around on her bed, facing away from everyone, and it seems as if she’s declined the invitation. Everyone else slumps back, as if in defeat… and then Rachel begins to sing.

(This conceit of not facing one’s audience when singing immediately reminded me of Sia, an Australian singer/songwriter who now chooses not to show her face when she’s performing, to avoid the cult of celebrity and maintain a modicum of privacy. We’ll return to Sia and her recent work with dancer Maddie Ziegler and choreographer Ryan Heffington in a later essay; for now, we simply want to put them on our radar.)

Rachel sings “I Wish I Knew,” in a slow, low, bluesy fashion, much more so than on the album recording. It’s sad, and lilting, and rather poignant within the context of the Underground in which they live.

I wish I knew what to do with you,

But the truth is I ain’t got a clue,

Do you? Do You?

I wish I had an idea of what I need,

But we, oh we, can’t know and that’s okay,

That’s okay.

This is a song that’s supposed to be sung to Rachel’s little brother, and the first stanza really works with this intention. She wishes she knew what to do with him, this little boy with the lost red backpack who is now in a wheelchair. When we get to the second stanza, though, it seems to become more self-referential. Being locked away in those glass cages, losing track of time, of course it makes sense to lose the sense of what one needs. But then the lyrics shift to “we” and it’s like Rachel is singing to the whole group that this is okay, it has to be okay, because none of this is really their fault.

This song transitions to the final scene upstairs, which we’ll cover a bit more in depth a little bit later, but it’s nice hearing Van Etten sing while we get shots of Hap’s kitchen, now adorned with Braille labels for Prairie to find her way around. (The first shop upstairs is of a kitchen cabinet labeled “glasses” in Braille, followed by a salt shaker labeled “salt” and a pepper shaker that has “soap” labeled on it, upside down, strangely enough.) Prairie spills coffee, and the song ends.

The second song comes right at the end, when Prairie is running through the woods. At first it sounds like a continuation of Van Etten’s earlier song, so similar is it in style and cadence, but it’s actually a cover of “It’s a Wonderful World,” written by Bob Thiele and George David Weiss, performed and popularized by Louis Armstrong, back in 1967. The song itself is pure schmaltz, a ballad of pure gratitude for the beauty of the world around us, but with Van Etten’s rendition, slow and laden with minor notes, it becomes imbued with sadness and irony.

I see skies of blue and clouds of white

The bright blessed day, the dark sacred night

And I think to myself what a wonderful world.

For it’s not a bright blue day with clouds of white, nor a dark night—the skies are grey and steely, the wind whips through Prairie’s hair, the trees stripped bare and the ground hibernating under a mantle of copper and brown, even the parts that have been strip mined. And it’s not like Prairie can see any of this anyways, she’s blind, and yet after this period of isolation and imprisonment, to suddenly taste freedom, would an environment even as harsh as this seem like a wonderful world?

BBA

BBA

So, we were talking about Betty Broderick-Allen, or “BBA” as Steve calls her, and her lovely bird pin that she’s wearing as she’s sitting in the car listening to her phone messages, communications left behind by a lawyer, Rod Spence… and then what’s presumably the last message left by her late brother.

Rod Spence is reminding BBA that there’s the matter of her brother’s will to attend to. Which she keeps putting off. Spence doesn’t actually say much of import here, but damn that’s an interesting name. “Roderick” means “famous power” and “Rodney” derives from “Hroda’s Island,” which you just know I’m going to take as an invocation to LOST. (I have my reasons.) “Spence,” on the other hand, derives from “Spencer,” and a “spencer” is someone whose job it was to dispense the lord’s provisions. Rod Spence is the person responsible for dispensing the provisions of BBA’s brother.

But in what sense should BBA’s brother be considered a “lord”? Well, I’m glad I asked that question, because her brother’s name is Theo. “Theo” derives from the Greek for “god.” So here, then, we get a level of subtext beyond BBA’s feelings of sadness and guilt for the loss of her brother. No, this is more than that—we can also take this as a parallel world exploring her feelings about the death of God. This is reinforced by Theo’s message:

THEO: Hey, Otter. Theo. Just throwing out a line to see what comes back.

First, BBA has a nickname, “Otter.” Not quite a fish, but an aquatic animal nonetheless. And Theo here is “throwing out a line,” as if he were a fisherman. A fisher of men, perhaps, or a fisher king, however we want to posit it, it still plays into certain Christian mythologies, where “fishing” is a metaphor for finding people and helping them along on their spiritual journeys—and even more so, hooking people’s souls for salvation. So Theo, the “god” of this metaphor, is reaching out to Otter and hoping to save her from her own remorse.

No wonder she’s so taken with The OA.

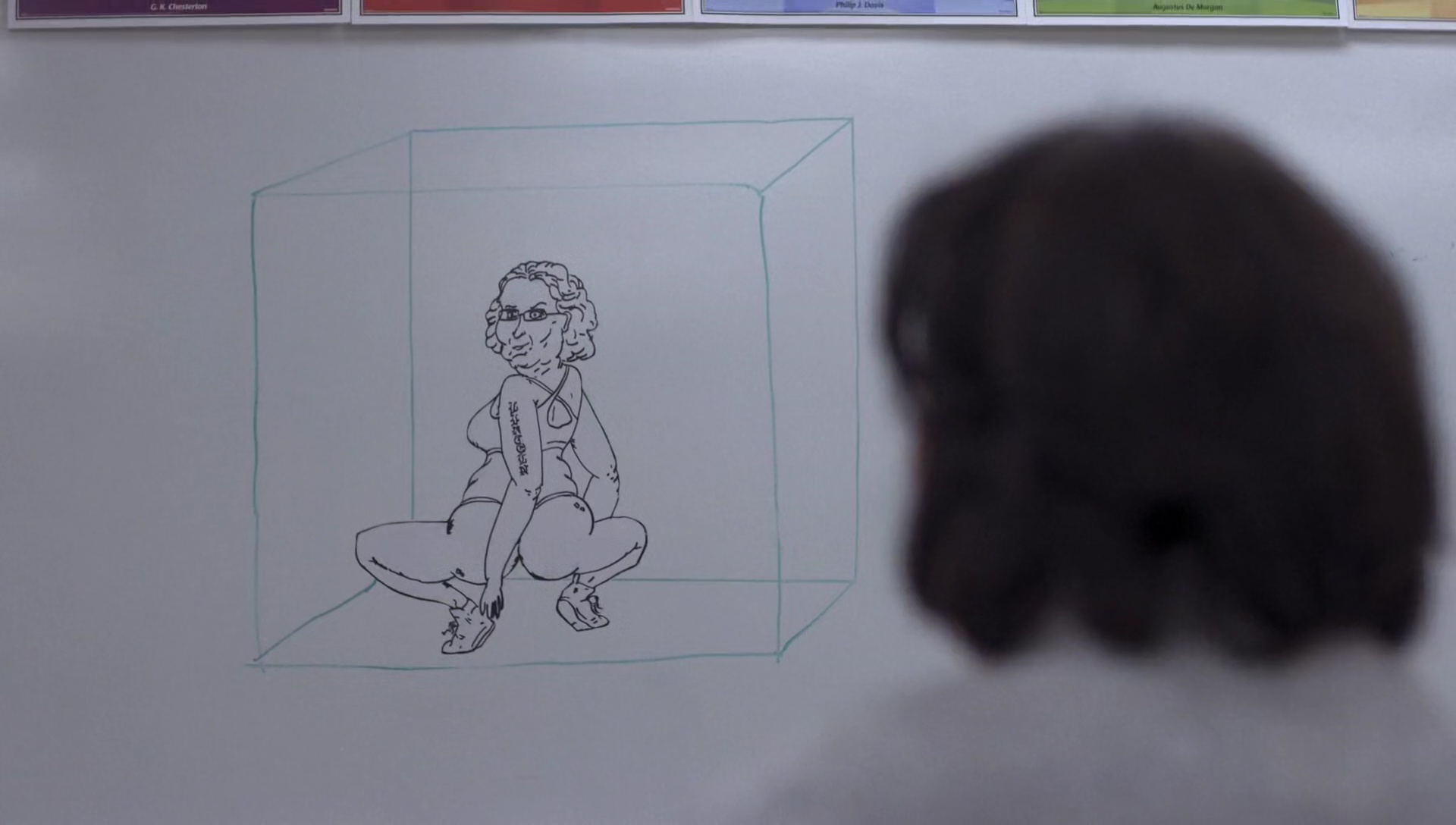

The other striking image with BBA occurs in the classroom: she finds a somewhat lewd picture of herself, drawn presumably by one of her students, up on her whiteboard. But rather than simply erase it, she draws a green box around the image, using perspective, then sits back and simply gazes at it. Reflecting on how she’s boxed in? The sides of the box aren’t filled in, they’re clear, like windows. BBA is learning to let go.

But not so much that she’s unwilling to dig into Steven a little bit. She tells him, as a reminder to head off to “alternative school,” that she “stuck out her neck for him.” Stuck out her neck, like a chicken?

Pat Knowler, Chicago Tribune

Hey, I said I had another LOST connection going on, and it comes to us in spades via Pat Knowler, the writer from the Chicago Tribune who accosts Nancy at the Costco (or Sam’s Club, whatever) about getting “Prairie” her story in book form.

Sadly, there’s not much to a name here. “Pat” means “noble” (think patrician) and “Knowler” means “dweller by the knoll,” though “kneller” means “noisy, disruptive.” The book that Pat wrote, Stolen, is about a young man named Jamie Price, which is slightly more interesting. “Price” fits in nicely with some of our other comments on The_OA, as it’s a name that means “son of the fiery warrior” and as such resonates with our broader concerns of power-oven and American football.

“Jamie,” on the other hand, derives from “Jacob,” and that is a name that strongly resonates with me. It’s a biblical name, and references a patriarch who had an “ascension” experience of his own.

Jacob left Beersheba, and went toward Haran. He came to the place and stayed there that night, because the sun had set. Taking one of the stones of the place, he put it under his head and lay down in that place to sleep. And he dreamed, and behold, there was a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven; and behold, the angels of God were ascending and descending on it! And behold, the Lord stood above it [or “beside him”] and said, “I am the Lord, the God of Abraham your father and the God of Isaac; the land on which you lie I will give to you and to your descendants; and your descendants shall be like the dust of the earth, and you shall spread abroad to the west and to the east and to the north and to the south; and by you and your descendants shall all the families of the earth bless themselves. Behold, I am with you and will keep you wherever you go, and will bring you back to this land; for I will not leave you until I have done that of which I have spoken to you.” Then Jacob awoke from his sleep and said, “Surely the Lord is in this place; and I did not know it.” And he was afraid, and said, “This is none other than the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven.

Jacob left Beersheba, and went toward Haran. He came to the place and stayed there that night, because the sun had set. Taking one of the stones of the place, he put it under his head and lay down in that place to sleep. And he dreamed, and behold, there was a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven; and behold, the angels of God were ascending and descending on it! And behold, the Lord stood above it [or “beside him”] and said, “I am the Lord, the God of Abraham your father and the God of Isaac; the land on which you lie I will give to you and to your descendants; and your descendants shall be like the dust of the earth, and you shall spread abroad to the west and to the east and to the north and to the south; and by you and your descendants shall all the families of the earth bless themselves. Behold, I am with you and will keep you wherever you go, and will bring you back to this land; for I will not leave you until I have done that of which I have spoken to you.” Then Jacob awoke from his sleep and said, “Surely the Lord is in this place; and I did not know it.” And he was afraid, and said, “This is none other than the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven.

From this passage we get the phrase “Jacob’s Ladder,” which is basically another axis mundi that connects the Ordinary World to the Other Side. A bridge, in other words, so very relevant to our proceedings here in The_OA. Well, as it turns out, there’s also a very important character in LOST named Jacob (for much the same reasons, I expect), the man who we discover is the “protector” or perhaps the “rulemaker” of The Island in that show.

Now, why is Jane so hung up on seeing LOST references in The_OA? Maybe she’s just seeing things that aren’t there? Well, that’s always possible. But then we get a character like Pat Knowler bringing up a set of numbers, twice (we could say twinned) that makes the hair on the back of Jane’s neck stand up on end:

PAT: I won the National Book Award for this. I’m only trying to say that my work is not sensationalistic. I spent 8 months with that family—

NANCY: I don’t care.

PAT: —15 weeks on the USA Today best-seller list.

8 months, 15 weeks. That’s an 815 reference, which LOST fans should recognize immediately as “Flight 815” – you know, the plane that crashed on the Island. The numbers come up again when Pat has dinner with the Johnsons:

OA: You wrote the book about the boy?

PAT: Jamie. Amazing young man.

OA: What is he like?

PAT: He was only 8 when he was abducted. Uh, 15 when he was rescued.

There it is again, 8 and 15, back to back. To back.

OA ends up declining to help Pat write this book. As Pat describes it, being able to write “the end” at the end of the book with Jamie Price helped Jamie to achieve a measure of closure and healing to his ordeal of abduction. But OA balks at this: “His story has an end… I’m… This is just beginning.” And it’s not that OA doesn’t want to tell the story—obviously she does, as evidenced with her time at the Abandoned House with the Five. But a story that has no end, well, that’s a story that’s always happening. A circular story, perhaps, or at least one with many parallel iterations.

HOMER: You got it?

RACHEL: He’s coming! He’s coming!

PRAIRIE: I got it, I got it. I got it. Wait. Wait, I lost it. I lost it!

HOMER: Catch it downstream! Downstream!

————–

FRENCH: Wait, so you lost Homer’s ring?

OA: Yeah.

Repeating Motifs

So, yeah, there are a lot of repeating motifs in The_OA, like the bathtub sequence we described earlier, which is mirrored by a transitional shot—after the conversation with Pat Knowler, we get a simple shot of OA washing up in the bath, and then we cut to the Abandoned House, where OA continues her story with the Five. A “transitional shot” is a shot that allows us to transition from one scene to another. It is, in other words, a bridge.

As we pointed out before, there’s plenty of water in this episode: the underground river running through the glass cages, ultimately connecting them (which Prairie finds out to some dismay when she tries to drink when everyone else is bathing), or the scene where Steve’s water is taken so that the young woman in “alternative school” (hmm, parallel reality) can make a point. And when Prairie describes to her fellow prisoners what she’d like to do when they escape, she says she’d like to swim. Be surrounded by water, held by something other than the dark.

There’s also the matter of the dead woman in the bathtub water, a dark mirror to Prairie’s own experience. The dead woman is named August, not by herself but as a nickname from the others. “August” means “great” or “venerable,” sharing the same Latin root of augere (to increase) that lies in the word “augment.” But that root is also the root of “augur,” a diviner or soothsayer, a prophet. What a strange juxtaposition – death as something prophesied, and great.

Songs and birds recur again as well. Rachel sings like an angel, frankly. More interestingly, when Prairie is sobbing by the River after the failed “ring in the Verizon bill” scheme, she’s snapped out of it by Homer in a most interesting way:

HOMER: Jump.

PRAIRIE: What?

HOMER: Stop talking. Start jumping. Jump. Again.

PRAIRIE: Please, I can’t.

HOMER: Oh, keep going. Do it, Prairie. Jump. Again. Flap your arms as you jump. Not silly, but for real. Like your arms are giant wings. Again. Higher. Again.

The girl who imagines herself as a fish is being taught to fly. Again and again. Over and over. Iterations. Eternal Return.

We also talked previously about “waking” and “sleeping” as metaphors for spiritual enlightenment, especially in the context of the prophetic dreams that Nina and Prairie had; Hap previously described the world around us as being in a “coma,” and Homer himself was in a coma after his football injury. Here, we get introduced to two new vectors of “sleeping” – the sleeping gas that Hap uses to knock out his prisoners, and the sleeping pills that Prairie uses to try to knock out Hap.

Hap says he uses the sleeping gas so his prisoners don’t have to “worry,” which of course implies that what Hap is doing is indeed worrisome. I mean, I’d be worried, especially given that one of his prisoners, August, is a dead woman in a bathtub. In an ironic twist, though, it’s talking about sleeping gas that makes Hap fall asleep to the reality of what he’s got on his hands, namely a strong competent woman that he’s grossly underestimated simply because she’s blind: she takes this conversational opportunity to push Hap down the stairs and make her own escape.

An escape that she herself failed at by trying to use sleeping pills to knock out Hap. See? Everything that goes around, comes around.

Parsley, Sage, Rosemary, and Time

Parsley, Sage, Rosemary, and Time

Let’s talk about food. We’ve kind of touched on this before—like, when Nina ate birds’ eggs the morning of her near-death experience. Prairie eating oysters with Hap; in The Hymn of the Pearl, eating food in Egypt and falling into a stupor. In “Champion,” there’s all kinds of stuff going on with food, throughout the chapter, and with all kinds of implications, alchemical implications.

Take the beet soup that Prairie makes for Hap, which just happens to have sleeping powder in it. Hmm, sounds familiar. Prairie’s trying to take the role of Egypt here, which is exactly the opposite position she really needs to take, at least when we consider this all as metaphor for her journey (as opposed to addressing just the literal aspects of her condition). She’s stepped into a position of power, and tries to exercise power-over her captor. It’s completely understandable, trying to manipulate the system, but the problem with system manipulation is that it doesn’t actually challenge the underlying assumptions of the system; instead, it ends up perpetuating them.

Mmm, that’s a big bite to swallow.

It’s an interesting soup that she makes Hap, even before the addition of the sleeping powder. It’s a beet stew that Prairie’s father taught her to make—so this is something laden with both childhood experience and metaphorical implications (the “father” being a representative of the Divine in this case), a point that’s emphasized with the primary ingredient:

HAP: Why do Russians love beets so much?

PRAIRIE: Beets survive frost.

HAP: Hmm. Of course. Something always survives.

Beets represent the ability to overcome death, to realize a kind of rebirth. They’re also RED in color, which has alchemical significance (and Prairie is performing alchemy here, making this stew); the rubedo stage of the Great Work is where the work of integration occurs, a “reddening” whereby the opposites of the ordinary world and the divine are wedded together.

But it isn’t this reddening that Hap reacts to. Rather, it’s the “tomato” paste (another Reddening, but without the divine implications) in one of the other stock ingredients. Being allergic, Hap isn’t just in danger of falling asleep, but nearly has his own near-death experience. And this is such a great sequence—it’s at this point that Prairie has to save Hap, lest the other “starve” to death in the basement, despite the automated food pellets. It’s at this point that Prairie finds Homer’s ring in the bathroom, and drops it in the bathtub water where August rests in peace.

Food runs through this entire chapter. Right at the very beginning, we see Nancy shopping for groceries, as she’s accosted by Pat Knowler. In the next scene, they’re all having dinner together at the Johnsons’ house, eating some Little Caesar’s pizza (light on the tomato sauce, but not lacking in allusion, for a “little Caesar” is akin to the Gnostic demiurge), while Pat talks about being a vegan, “not a political or spiritual decision,” she says, but actually rooted in “wanting to take control” of what she puts in her mouth. While in Hap’s basement, we see automated food pellets being delivered to the prisoners, an entirely different form of control being exercised by Hap.

And then there’s the great scene early in Prairie’s time at Hap’s, when he lets her upstairs for the first time, ostensibly just to feel the sunlight on her face. Prairie finds a knife, but doesn’t use it for attack; rather, she applies it to a loaf of bread, and quickly learns her way around the kitchen to make Hap a chicken sandwich. The chicken, of course, plays into all the bird symbolism we’ve seen so far. Here, Prairie takes flight, gaining all kinds of good things for herself: a measure of freedom from Hap, and the gratitude of the other prisoners, for Prairie is certainly adept at manipulating a system she’s barely familiar with.

SCOTT: Why’d you have to fuck it up with mustard?

Prairie puts mustard on the sandwiches she makes for Hap and the prisoners, something that Scott points out in particular. I’m reminded of the Parable of the Mustard Seed: “The Kingdom of Heaven is like a grain of mustard seed, which a man took, and sowed in his field; which indeed is smaller than all seeds. But when it is grown, it is greater than the herbs, and becomes a tree, so that the birds of the air come and lodge in its branches.” Nice, the reference to birds here, too. But what’s actually interesting here is the implication that by making a bird sandwich, in a particular way, Prairie is opening up a door to “the kingdom of heaven,” if not actually creating it in the first place.

This is such a far cry from how the chapter ends, though. For while Prairie is quite resourceful in complying with her dominator, and manipulating that system, she still can’t escape it in the end. So she resorts to rebellion, to violence, and actually gets further than she ever had before, even though it’s not nearly far enough. And again, there are all kinds of interesting details that converge here:

HAP: The gas is so you… you don’t have to worry. Look, Prairie, all great work… important work, comes at great cost.

I love this union of the sleeping gas and the phrase “great work” in this dialogue. Prairie pushes Hap down the stairs at this point, depositing him in the dungeon that he’s kept for his prisoners. And then she grabs a cast iron skillet – a tool for cooking, and she breaks open a window (destroying that which prevents connection) through which she escapes, however temporarily. She winds her way through the trees, while we hear Rachel singing in voice-over. But her violence is, in the end, met with more violence, as the butt of a rifle knocks her out as the wind whips through the (talk about sleeping gas!).

So that’s where we end the chapter, with a cliffhanger at the edge of a cliff – see, this text is perhaps more self-aware than we’ve given it credit for.

I do hope you remembered to save a bite to eat. You can go ahead and swallow it now.

You know who you are.

March 9, 2017 @ 11:01 am

Little to add, other than I am so tremendously glad that this exists, because the OA deserves some really meaty analysis. Great stuff.

March 9, 2017 @ 4:10 pm

Welcome back – hope you had a nice trip. Great stuff, as always. The density of the writing and mis-en-scene of this show is quite impressive…I’m definitely going to have to “go back” and rewatch to catch all of the details you’re pointing out.

March 13, 2017 @ 12:59 pm

M.C.Escher painting relevant

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/4/4c/Sky_and_Water_I.jpg