Wiping Moscow From The Face of the Earth Would Be Fine (The Last War in Albion Part 9: Starblazer, the Pulps, Russian Structuralism)

This is the fourth of five installments of Chapter Two of The Last War in Albion. You can still grab the ebook single of chapters one and two at Amazon, Amazon UK, and Smashwords. Please consider helping support this project by buying a copy.

PREVIOUSLY IN THE LAST WAR IN ALBION: Grant Morrison’s contributions to Starblazer consisted of action-packed adventure stories that always came back with the editorial note “more space combat.” This style of writing owes much to the cheap populist fiction of the American pulps and British penny dreadfuls, which favored a dynamic and breathless prose style…

“Wiping Moscow from the face of the earth would be fine.” – Warren Ellis recounting editorial guidance from Hasbro, 2008

Indeed, the absence of this hypnotic prose in favor of banal action set pieces provides at least part of the explanation for why the John Carter film was so singularly unable to replicate the narrative magic of its source text. Their text was a sort of verbal spectacle, doing the same thing to language that Siegel and Shuster did for the comics page.

But the chief engine of the narrative was the cliffhanger. A story’s job was to be exciting for a certain number of words, then to end on a big cliffhanger so the reader would want to see what happens next week. Their cryptic introductions serve as replacements for the lead-ins from previous installments, and the stories quickly get into their own distinctive rhythms. Chapter Four of A Princess of Mars ends with the revelation of a creature described as “about the size of a Shetland pony, but its head bore a slight resemblance to that of a frog, except that the jaws were equipped with three rows of long, sharp tusks.” The chapter then leaves off, more questions than answers.

|

| Figure 69: Cover of the tenth issue of Eagle, featuring a page of Dan Dare: Pilot of the Future (Frank Hampson, 1950) |

This structure survived the pulps’ gradual evolution into comics. In the UK the successors were things like The Beano and The Dandy, but also titles like Eagle, Marcus Morris’s 1950 comics magazine headlined by two brightly coloured pages of Frank Hampson and his studio’s Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future. Dan Dare is one of the most iconic figures in British comics, and will appear several times in the course of the War. A square-jawed pilot meant to evoke the heroism of the RAF in the still-vividly remembered Battle of Britain, Dan Dare fought the villainous Treens, coded blatantly as space Nazis and led by the fiendish Mekon. Dare was in the tradition of action heroes like Flash Gordon, Alex Raymond’s 1930s newspaper comic. In the US they were anthologies like Action Comics featuring adventures of various different heroic figures. Some featured cliffhangers, while others resolved stories with emphatic promises of further adventures with popular characters like Superman.

Even these shorter stories had their breathless quality, however, and it’s telling that the digest format, which didn’t serialize its stories, got a similarly punctuated effect by its small page sizes. Because it’s difficult to get more than three panels onto a single page and complex page layouts are simply impossible (to say nothing of improbable on the cheap wages and fast schedule of Starblazer), stories acquire a momentum. Grant Morrison uses this format to reasonable effect, executing fast shifts among settings to cram more action into his comic, and the short bursts of plot exposition punctuated by action sequences serve all the same narrative functions as cliffhangers.

|

| Figure 70: A Western-style shootout in the frozen northland featuring Herne, the heroic space pilot in Starblazer #15 (Grant Morrison, 1979) |

What Morrison does that’s particularly clever, though, is to use the genre-blending techniques he was already experimenting with in Near Myths on the space combat action of Starblazer. This is why Herne can wander through what is obviously a bit taken out of a western, only set in a frozen northland and in the course of a story about robotic space conquerers. The episodic structure of the plot lets Morrison switch among genre codes, so that, for instance, a hard-boiled detective in the Hammett/Marlowe style can meet a barbarian princess straight out of Robert E. Howard as they race around space stations like a Flash Gordon serial.

But these elisions of genre had always been part of the pulps. Robert E. Howard’s sword and sorcery epics were close cousins of H.P. Lovecraft’s cosmic horror, and Burroughs’s planetary romances were in many ways distinguishable from Conan stories only because they have a Civil War veteran in space as the main character and not a sword-wielding barbarian. Michael Moorcock’s genre experiments are, in this regard, the natural extension of his boyhood days editing the Sexton Blake Library and Tarzan Adventures, to which he contributed his own Sojan the Swordsman “sword and sorcery” character, the decision to launch Jerry Cornelius with a rewritten Elric of Melniboné story coming off as a wry joke about just how interchangeable the plots of all of these are. The mass success of Star Wars is nothing more than George Lucas realizing that cinema was capable of executing the genre fusion of monks wielding laser swords in a space-set Eroll Flynn movie about a young farmboy, and that what worked in the pulps would probably work on the screen. Sure enough, it did.

|

| Figure 71: An early Michael Moorcock story from his time editing Tarzan Adventures (1958) |

But there’s a question in all of this that may be non-obvious, which is why is it so easy to switch around among the seemingly disparate genres of noir detectives, sword and sorcery fantasy, and space adventure. These genres are clearly natural fits for each other in practice, but what is it that enables them to work so well together? More broadly, why does genre-crossing work in the first place?

|

| Figure 72: The intimate and personal style of an autobiographical comic like Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home is visually distinct… (2006) |

First it is necessary to understand genre, a word with two distinct but related meanings. In a classical sense, at least, genre describes structure as much as content. This is true even to the extent that Aristotle, in The Poetics, discussing how epics are distinct from tragedies not just in their plot structure, but in the fact that epics are written in hexameter. That is to say, it’s not merely the fact that tragedies have a particular plot structure about “a man who is not eminently good and just, yet whose misfortune is brought about not by vice or depravity, but by some error or frailty,” but that tragedies are distinct from epics on the basic level of the rhythm of language used within them. Even today this distinction applies to a significant extent – consider, for instance, the way in which personal and autobiographical comics will use a sparser visual style that suggests a single artist compared to the slick and stylized approach of American superhero comics, where even though the distinctive styles of individual artists are discernible the imagery is processed so as to (quite accurately) look like it comes from a corporate gestalt and not a single visionary. Different types of stories are told in fundamentally different ways.

|

| Figure 73: …from the kinetic excess of Rob Liefeld’s cover to Cable and Deadpool #1 (2004) |

In the early 20th century this sort of approach to genre was in vogue through a set of critics known as structuralists. Structuralists were interested in describing things in terms of larger, often deterministic structures. A representative example is Russian folklorist Vladimir Propp, whose 1928 landmark Morphology of the Folktale, which attempted to create a generalized schema that all Russian folktales followed, thus allowing the folktales to be represented as quasi-mathematical formulas. Individual plot elements were assigned letters, so that I represents victory over the villain, with I1 referring to “victory in open battle,” I2 to “victory or superiority in a contest,” I3 to “winning at cards,” and I4 to “superiority in weighing.” Notably, however, within this any amount of variation in particulars can exist – any plot incident in which the hero defeats the villain in a contest is an I2 regardless of whether the contest is a test of strength, an archery competition, or any other competition. A given Proppian formula, in other words, can be filled in with an infinite number of possible details.

|

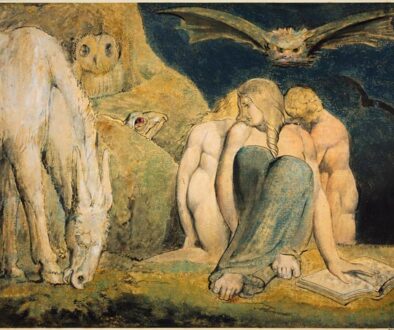

| Figure 74: Narrative as understood by Vladimir Propp |

Indeed, one can even expand the Proppian formula to include details that would be anachronistic to a Russian folktale. There is no inherent reason one could not construct a story that strictly followed Proppian structure, but where the open battle of I1 is a spaceship battle, or a shootout in the wild west. Such a story would fail to be a Russian folktale only for the incidental reason that spaceships and the wild west were not popular concerns of 19th century Russian storytellers. What matters, in this sense of genre, is only the broadest and most abstracted shape of the plot.

There is, however, a second sense of genre in which the word refers not to the structure of stories but to certain elements within them. These are genres like fantasy, science-fiction, and westerns that are defined by the presence of magic or spaceships or a particular geographic/historical setting as opposed to by what happens in them. These genres are characterized by an almost infinite level of granularity, so that fantasy can be broken down into “high fantasy,” “dark fantasy, “sword and sorcery,” et cetera, allowing for no end of debate as to whether or not A Princess of Mars is most accurately described as “planetary romance” or “sword and planet.” But these genres do not define the plots of their stories so much as the tone generated by the plot devices. It is worth comparing two of Morrison’s Starblazer stories in this regard: “The Ring of Gofannon” and “The Last Man on Earth.” Both involves a lengthy journey to recover a powerful object – the eponymous Ring of Gofannon and the “stardust equation.” In each case, the journey has multiple distinct steps in which the protagonist encounters and overcomes new threats. The difference is that in one the threats are spaceships and mercenaries with laser guns, and in the other they’re air elementals and dragons.

It would, however, be trivial to switch them. A fantasy story in which some mad king sends a hero on a quest for a powerful weapon that the hero eventually uses to overthrow the king is as easy to imagine as a sci-fi one in which the central twist of the “ring” being sought is not a piece of jewelry but a circuitous route on a map. The basic content of the two stories, in other words, is not genre-specific, and either one could trivially be reworked into another genre. Arguably, in fact, one is simply Morrison reworking the other.

|

| Figure 75: The lone genre film to crack the top ten in 1950 was Compton Bennet and Andrew Marton’s adaptation of King Solomon’s Mines |

All of this conspires to make an important point about the terrain the War is fought on. The comics industries that Grant Morrison and Alan Moore affected were ahead of the trend in a general shift the nature of popular culture. What might broadly be called tales of the fantastic – science fiction, fantasy, and horror, but really a wide swath of genres that developed in cheap serialized print media in the 20th century, including superheroes – became increasingly popular in film over the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Consider the ten top-grossing movies of each of the years following the end of World War II – a significant period of cultural shift in both America and the United Kingdom. This requires some marginal calls – does Song of the South count as fantasy, for instance? But a general narrative can be traced. From 1946-1979, the average number of films featuring some sort of sci-fi/fantasy elements in the top ten was .88. From 1979 – the year Moore and Morrison got their professional starts – to 1987 – the year of Watchmen (and the year before Animal Man) – the number is 2.3. 1987 is the last year to date that there were no sci-fi/fantasy films in the top ten. From 1988-2000, the turn of the millennium, and the end-date of The Invisibles (and in the middle of Promethea) it was 3.8. 2000 also marked the release of X-Men, the film that launched the contemporary superhero boom. From 2001 to the present day, using the current 2013 numbers, it has been 6.5, 2001 having been the first year to have a majority of its top ten films be sci-fi/fantasy.

These numbers do not, to be clear, represent a rise in pulp-derived action/adventure films. Rather, they represent an increase in the presence of specifically fantastic elements in films, most of which but not all of which are also action/adventure films. Nor do they suggest some direct causality whereby Grant Morrison’s sigilistic working in The Invisibles causally increased the number of sci-fi films being made, although it is certainly the case that they did increase sharply the year after that comic finished. The rise of sci-fi/fantasy happened gradually over decades. However, it is most certainly the case that the people who produced this increasing torrent of sci-fi/fantasy were influenced by the pulps and cheap serialized material that existed during their childhoods.

|

| Figure 76: Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind was one of several films in the late 1970s sci-fi boom (1977) |

So in the late 1970s, as this tide began in film with things like Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and Alien major filmmakers in the genre like George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and Ridley Scott were inspired by the pulp fiction of their childhoods – 1950s America for George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, and late 40s/early 50s Britain for Ridley Scott. All of this took place in the context of other historical shifts, of course, but it was the trend that Moore and Morrison were swept up in, and, eventually, came to find themselves appearing to steer. Film and serialized print, after all, had always been bedfellows. Film adapted popular serialized print stories and genres – the films that were popular in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s were still action-adventure stories derived from the pulps, but they were war stories and westerns that lacked sci-fi/fantasy elements.

But the lines between these pulp genres often blur, much as the line between superheroes and the pulps blurs. Starblazer was the sci-fi/fantasy sister title to the straight war digest Commando, also published by DC Thomson. [continued]

September 12, 2013 @ 1:04 am

You raise some interesting points at the end regarding the rise of the fantastic in popular culture (and dodge around wehther this is a societal shift that allows the rise or technological shifts that make the fantastic easier and more effective to realise), but you seem to be skipping a generation or conflating pre-war pulp – what is generally known as pulp – and the post-war genre writing. To claim that both Dan Dare and A Princess of Mars are both "pulp" is a huge leap. The cultures and societies that produced either are wildly different and have that great big war in the middle.

Additionally, Moore and Morrison are a generation removed from the first pulps and the first reactions to them. They are being influenced by those who were influenced by the first generation – film makers like Lucas (who you identify), and TV shows like Doctor Who (of course) or the Avengers or Batman '66 (pulp fiction crossing media with no attempt at translation to the new medium), that play with these older tropes and give permission for this play. Isn't Dan Dare a perfect example of this cross genreism (which is not a word), WWII in space. Perhaps I read too hastily, but you seem to be insinuating the two main protagonists of The War are children of the pulps, but aren't they really the grandchildren?

September 12, 2013 @ 3:03 am

Lester Dent, who wrote most of the Doc Savage pulps, documented his process in this little essay. Don't know its provenance, but it's a great example of writing as an assembly line.

Dirty 30s! – The Lester Dent Pulp Paper Master Fiction Plot

http://www.paper-dragon.com/1939/dent.html

"This is a formula, a master plot, for any 6000 word pulp story. It has worked on adventure, detective, western and war-air. It tells exactly where to put everything. It shows definitely just what must happen in each successive thousand words."

September 12, 2013 @ 5:12 am

Burroughs’s planetary romances were in many ways Conan stories reworked into outer space

This makes it sound as though Conan came first. John Carter first appeared in 1912 (as did Tarzan, yet another influence on Conan), while Conan didn't make his first appearance until 1932.

September 12, 2013 @ 5:15 am

does Song of the South count as fantasy, for instance

I think so; if the framing device made it non-fantasy, then the it's-all-a-dream framing device of Wizard of Oz would make that non-fantasy too.

September 12, 2013 @ 7:11 am

Nothing to do with the War, or the nature of genre, or any of that stuff, but I'd just like to say that if anyone, staring in disbelief at that Liefeld cover, thought "I wish someone had devoted a lengthy paragraph to mockingly describing how ludicrous Cable looks", well, enjoy:

http://web.archive.org/web/20080201080044/http://www.thexaxis.com/cabledeadpool/cabledeadpool1.htm

September 12, 2013 @ 7:42 am

I'd just like to praise you for implicitly positing Alison Bechdel and Rob Liefeld as polar extremes… a dichotomy that works in so many ways (not least quality).

September 12, 2013 @ 7:57 am

Good point – I've reworked the line.

September 12, 2013 @ 7:58 am

Ooh, thank you. /quickly reworks last part of the chapter.

September 12, 2013 @ 8:36 am

Descendants in general is really the important part of the claim – in this case I'm less interested in the chain of influence as the fact that they were working within the old pulp genres and trying to reinvent them in a particular way. The focus on the pulps and their immediate successors like Dan Dare and American superhero comics is largely about tracing the history of a particular kind of narrative that Moore and Morrison disrupted.

September 12, 2013 @ 11:10 am

How much is the rise in the amount of fantasy/sci-fi in the top ten films is down to the decreasing costs of more and more complicated and 'realistic' special effects that form an integral part of what is perceived as block-buster films? There is also Morrison's assertion that Super-heroes are migrating from comics to the moving picture.

I suppose comics in general have been ahead of this particular curve purely on the basis that fantastic sequences can be as easily produced as the more mundane. The apex of this approach been Ellis & Hitch's The Authority which was of course referred to as 'wide-screen' comics in reference to the cinematic epic.

Looking forward to your opinion on Morrison & Hughes's subtle anti-Thatcher satire Dare.

September 12, 2013 @ 12:58 pm

Yes, thanks brownstudy – and thank you, too, Philip, for bringing up Propp. Both have given me some bedtime reading!

September 12, 2013 @ 4:02 pm

Though there's still the difference that Conan's ethics are a bit more flexible than the ethics of a Burroughs hero.

September 12, 2013 @ 4:16 pm

Happy to be of service! I've had that link for years wondering where the hell I could deploy it…

September 12, 2013 @ 6:26 pm

The ending of Song of the South has something of a narrative collapse which I believe Phil would appreciate, despite it being an awkward and abrupt end to a rather slow-moving live-action film with brief bits of animation where it comes alive.

…sorry, that sentence was crappy. But you get my point, I hope. :-S

September 12, 2013 @ 7:56 pm

So which is better, B for Beretta or The Unsmellables?

September 12, 2013 @ 11:32 pm

This is not a review blog. Mind you, if it were, you'd be better off comparing Gloom Patrol and Marbleman (latterly Mackerelman).

Alternatively:

"There's only one way to find out FIGHT!!"</Harry Hill>