Killing in the Name Of

Fascism isn’t socialism. This isn’t the sort of thing that one should have to say, but apparently it is.

Politics has content as well as form. It is not, as fascism always tries to make it, a game of aesthetics. No matter how superficially similar fascist and antifascists may be – and I contend that, with a very little good-faith scrutiny, they are not actually very similar at all – there is a world of difference, so much difference on every level that equivalence of any kind is a gross falsehood, a catastrophic failure of understanding. It is the content of political action which gives it meaning, not the form. And the content always ultimately derives from the class content, which ultimately derives from the class basis. The class content and basis of fascism, whatever the rhetoric, is bourgeois, based on the defence of capital either directly or via the defence of those divisions and oppressions which are both generated by and bolster the rule of capital. They don’t need to be generated by or to bolster capital to be wrong, but they are and do. The class content and basis of antifascism, by contrast, is found in defensive reaction against the fascists’ project to divide the working class along lines of race in the interests of capital.

This is ultimately both why people can pull the “the nazis were socialists” bullshit – “National Socialists! It’s even in the name!” – and why they’re wrong. The question of why the Nazis called themselves socialists, and why fascism generally often flirts with left-wing rhetoric and even some superficially left-wing ideas, is complex. What isn’t complex is the question of whether fascism is or is not, ultimately, a phenomenon of the left. The answer is no, because of its content, which is ultimately its class content, and which is ultimately determinable via an examination of what it actually does.

Fascism as a governmental form was a form of response to a crisis of capital accumulation. Fascism as a movement – at least in its classical form – also tends to arise as a reaction to the rise of a challenge, or perceived challenge, to capitalism from the working class, and from socialism. Part of its process of evolution as a mass movement tends to be a certain aping of left movements in an attempt to assimilate some of their popularity and membership while opposing them. The Nazis arose in Germany on the crest of a wave of reactionary, nationalist counter-revolution against the German Revolution of 1918-23, which caused the Kaiser to abdicate and flee, and the German generals to capitulate to the Allies in the First World War. The defeat of the revolution was a combination of sharp turning points and slow decay. But socialism remained a hugely popular idea with the working masses of Germany throughout the 20s and 30s.

The ostensibly socialist Social Democratic Party (SPD) was huge, with a vast network of workers’ clubs, magazines, papers, camps, youth organisations, etc.

And what of Moore? Where was he as the company he forsook remade itself in what they imagined his image to be? How did the Prophet of Eternity respond to what he had wrought?

And what of Moore? Where was he as the company he forsook remade itself in what they imagined his image to be? How did the Prophet of Eternity respond to what he had wrought?

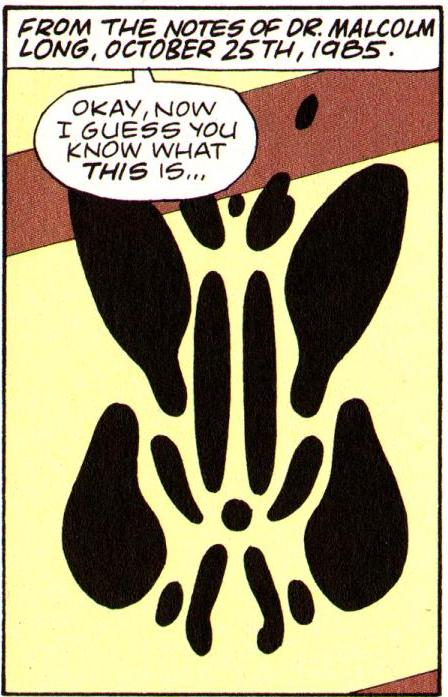

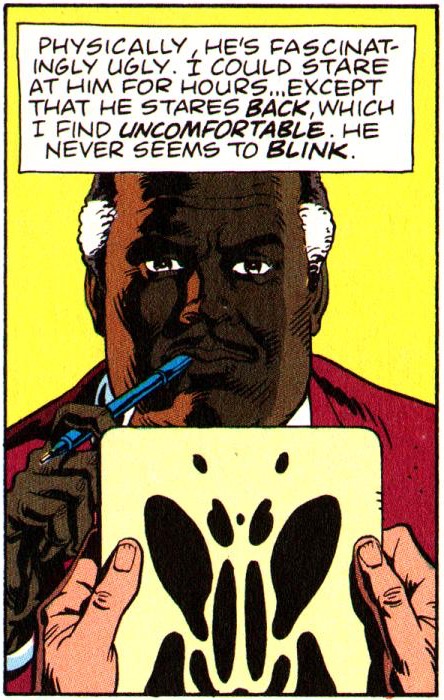

The core of the problem was that from DC’s perspective, the lesson of Watchmen could only ever be one thing: things like this sold. And within the post-Crisis reality of the direct market, what DC specifically cared about was what fans said. The simple reality is that what the vocal fans who showed up and bought Watchmen in their specialist comic book stores liked most about the book wasn’t the moving explorations of sexuality in “A Brother To Dragons”; it was Rorschach being a moody badass in “The Abyss Gazes Also.” And so this is what DC imitated.

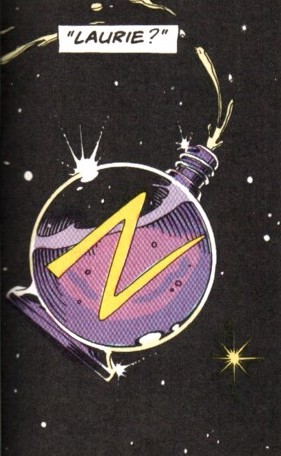

The core of the problem was that from DC’s perspective, the lesson of Watchmen could only ever be one thing: things like this sold. And within the post-Crisis reality of the direct market, what DC specifically cared about was what fans said. The simple reality is that what the vocal fans who showed up and bought Watchmen in their specialist comic book stores liked most about the book wasn’t the moving explorations of sexuality in “A Brother To Dragons”; it was Rorschach being a moody badass in “The Abyss Gazes Also.” And so this is what DC imitated. Consider January of 1987, the month that Moore finally came to the decision that he would not accept any new work from DC. In addition to Watchmen #8, in which Rorschach breaks out of prison with the help of Dan and Laurie after violently murdering his way through a number of inmates, high profile comics being released included the final issue of Legends, DC’s first attempt to duplicate the success of Crisis on Infinite Earths, two issues of John Byrne’s Superman run, and an issue of George Pérez’s Wonder Woman. In more grim and gritty terms, DC released an issue of Vigilante, with its right-wing fantasy of extrajudicial executions, and The Question, which saw Denny O’Neil putting his own spin on Rorschach’s source material, and the third installment of Frank Miller’s post-Crisis Batman: Year One relaunch. But even within the Batman line, that same month saw the release of Detective Comics #573, a goofball issue featuring the Mad Hatter, albeit one that ends with Robin being shot and gravely wounded. But DC still had at least one eye firmly situated on the past. Other titles included Infinity Inc., co-written by Roy Thomas, a twenty-year veteran of the industry who had succeeded Stan Lee as editor in chief at Marvel Comics.…

Consider January of 1987, the month that Moore finally came to the decision that he would not accept any new work from DC. In addition to Watchmen #8, in which Rorschach breaks out of prison with the help of Dan and Laurie after violently murdering his way through a number of inmates, high profile comics being released included the final issue of Legends, DC’s first attempt to duplicate the success of Crisis on Infinite Earths, two issues of John Byrne’s Superman run, and an issue of George Pérez’s Wonder Woman. In more grim and gritty terms, DC released an issue of Vigilante, with its right-wing fantasy of extrajudicial executions, and The Question, which saw Denny O’Neil putting his own spin on Rorschach’s source material, and the third installment of Frank Miller’s post-Crisis Batman: Year One relaunch. But even within the Batman line, that same month saw the release of Detective Comics #573, a goofball issue featuring the Mad Hatter, albeit one that ends with Robin being shot and gravely wounded. But DC still had at least one eye firmly situated on the past. Other titles included Infinity Inc., co-written by Roy Thomas, a twenty-year veteran of the industry who had succeeded Stan Lee as editor in chief at Marvel Comics.… There is, however, another important sense in which Rorschach represents a myopia within Watchmen and, more broadly, Moore’s larger artistic vision. As mentioned, a crucial part of Rorschach’s psychology is his tortured relationship with sexuality. Sex is a major theme of both Watchmen and Moore’s career, and one that he has much of value to say about, but there is something unseemly about the directness with which Rorschach’s disgust with sex is pathologized, not least because it’s a character trait inherited from his underlying relationship with the apparently asexual Steve Ditko. More broadly, there is something oversimplified and unsatisfying in Moore’s approach to sexuality—a flaw intimately connected to his persistent inadequacy on the subject of sexual assault. This would be a relatively minor issue were it not for the awkward fact that the relationship between superheroes and sexuality is one of the comic’s major themes.

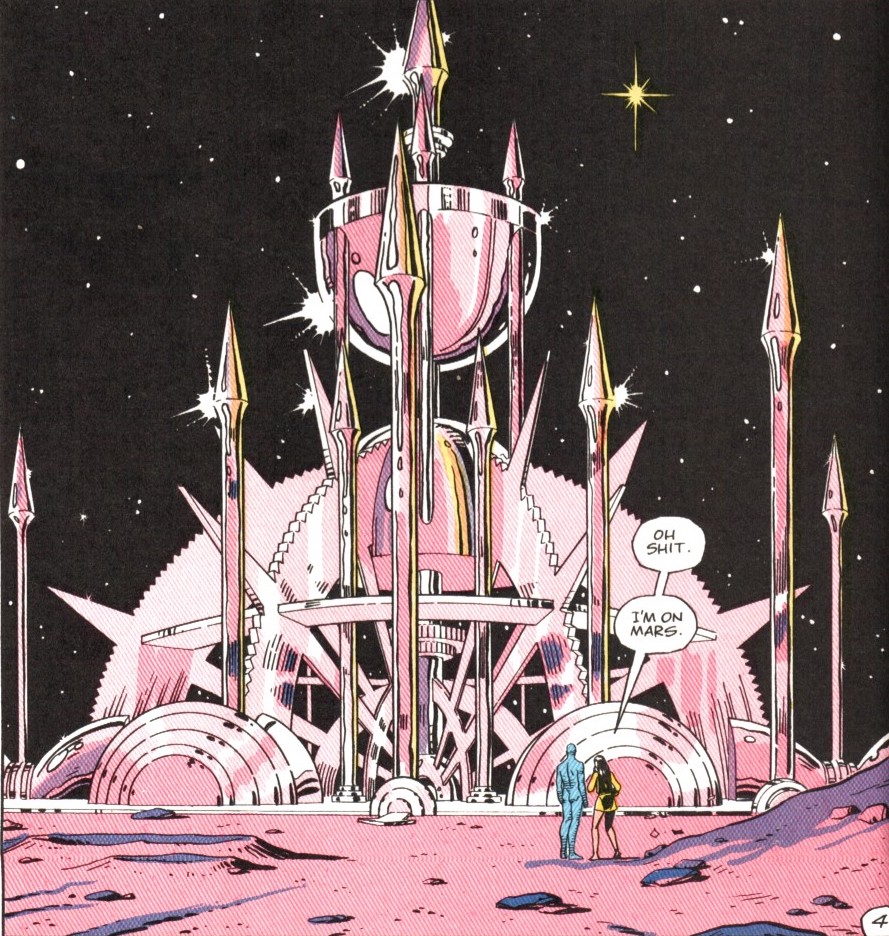

There is, however, another important sense in which Rorschach represents a myopia within Watchmen and, more broadly, Moore’s larger artistic vision. As mentioned, a crucial part of Rorschach’s psychology is his tortured relationship with sexuality. Sex is a major theme of both Watchmen and Moore’s career, and one that he has much of value to say about, but there is something unseemly about the directness with which Rorschach’s disgust with sex is pathologized, not least because it’s a character trait inherited from his underlying relationship with the apparently asexual Steve Ditko. More broadly, there is something oversimplified and unsatisfying in Moore’s approach to sexuality—a flaw intimately connected to his persistent inadequacy on the subject of sexual assault. This would be a relatively minor issue were it not for the awkward fact that the relationship between superheroes and sexuality is one of the comic’s major themes. The theme of sex within Watchmen ignites in the seventh issue, “A Brother to Dragons,” which forms, along with “The Abyss Gazes Also,” a symmetrical axis at the center of the series. Watchmen can be divided into two types of issues: ensemble pieces that feature a large cross-section of the cast, and character-focused issues that provide backgrounds and meditations on individual heroes. The first half of the book alternates between these two types, with “At Midnight, All the Agents,” “The Judge of All the Earth,” and “Fearful Symmetry” jumping among multiple points of view while “Absent Friends,” “Watchmaker,” and “The Abyss Gazes Also” focus on the Comedian, Dr. Manhattan, and Rorschach respectively. The second half also alternates back and forth, but here it is the odd-numbered issues that are character-focused, looking at Ozymandias, Silk Spectre, and, in “A Brother To Dragons,” Night Owl.

The theme of sex within Watchmen ignites in the seventh issue, “A Brother to Dragons,” which forms, along with “The Abyss Gazes Also,” a symmetrical axis at the center of the series. Watchmen can be divided into two types of issues: ensemble pieces that feature a large cross-section of the cast, and character-focused issues that provide backgrounds and meditations on individual heroes. The first half of the book alternates between these two types, with “At Midnight, All the Agents,” “The Judge of All the Earth,” and “Fearful Symmetry” jumping among multiple points of view while “Absent Friends,” “Watchmaker,” and “The Abyss Gazes Also” focus on the Comedian, Dr. Manhattan, and Rorschach respectively. The second half also alternates back and forth, but here it is the odd-numbered issues that are character-focused, looking at Ozymandias, Silk Spectre, and, in “A Brother To Dragons,” Night Owl. The line, of course, belongs to Rorschach, the glamorous poison at the heart of Watchmen’s appeal. Moore is self-effacing about the character these days, joking that his popularity is down to the fact that Moore “had forgotten that actually to a lot of comic fans that smelling, not having a girlfriend – these are actually kind of heroic.” But unlike a lot of Moore’s self-deprecation, there’s an edge to this quip. He’s emphasizing his failure to anticipate the reaction to Rorschach, but only as a means to insult Rorschach’s fans even more spectacularly. There are obviously a lot of things about Watchmen that have gone sour for Moore, but at times it seems that there is nothing he resents quite as deeply as the reception of Rorschach.

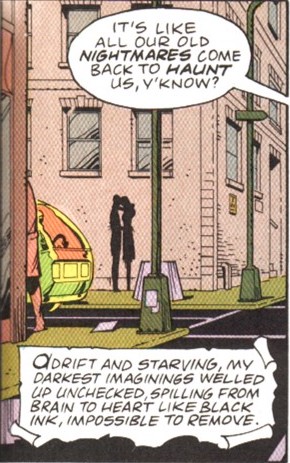

The line, of course, belongs to Rorschach, the glamorous poison at the heart of Watchmen’s appeal. Moore is self-effacing about the character these days, joking that his popularity is down to the fact that Moore “had forgotten that actually to a lot of comic fans that smelling, not having a girlfriend – these are actually kind of heroic.” But unlike a lot of Moore’s self-deprecation, there’s an edge to this quip. He’s emphasizing his failure to anticipate the reaction to Rorschach, but only as a means to insult Rorschach’s fans even more spectacularly. There are obviously a lot of things about Watchmen that have gone sour for Moore, but at times it seems that there is nothing he resents quite as deeply as the reception of Rorschach. The fundamental problem at the heart of this is simply that Rorschach is an unsettlingly fascinating character. Even Moore, for all the reservations he would come to have about him, freely admits that “Rorschach was one of the characters I enjoyed writing most.” And no wonder – think of a classic line in Watchmen and the odds are overwhelming that you’re thinking of a Rorschach line, probably either a bit of his opening monologue or “none of you understand. I’m not locked up in here with you. You’re locked up in here with me.” Whether or not one relates to the character, he is undeniably compelling, reliably giving the book a jolt of energy whenever he shows up.

The fundamental problem at the heart of this is simply that Rorschach is an unsettlingly fascinating character. Even Moore, for all the reservations he would come to have about him, freely admits that “Rorschach was one of the characters I enjoyed writing most.” And no wonder – think of a classic line in Watchmen and the odds are overwhelming that you’re thinking of a Rorschach line, probably either a bit of his opening monologue or “none of you understand. I’m not locked up in here with you. You’re locked up in here with me.” Whether or not one relates to the character, he is undeniably compelling, reliably giving the book a jolt of energy whenever he shows up._p01_(comichost-dcp).jpg) Moore’s disorientation and confusion in the wake of Watchmen is wholly understandable. Even reading Watchmen is, at times, enough to generate a sense of dazed exhaustion. And this is very much the point – an effect consciously generated by Moore’s use of the dense uniformity of the nine-panel grid. As Kieron Gillen puts it in Kieron Gillen Talks Watchmen, “if we’re talking about the many icons of Watchmen, [the nine-panel grid] is the invisible one. It underlies everything. We’re to watch these little boxes – hundreds of them – and make sense by combining them all into a larger piece of meaning. Watch,” he says, and snaps his fingers to cue his projectionist to advance his PowerPoint to a shot of Ozymandias watching his wall of television screens. Gillen talks about the comic as a “clockwork machine” in which “everything is predetermined. The forces that are put into motion mean this… the clock will carry on ticking, and if you read Watchmen enough you’ll know what the next tick is.” Gillen, here, is talking about the comic’s famously ambiguous ending, making a strong case that in fact there is only one possible “next step” for the book to take, and that the inevitable momentum of that step hangs impermeably over the entire work, which is in turn what Morrison speaks of when he talks about how the god of Watchmen is always shoving his cock in the reader’s face.

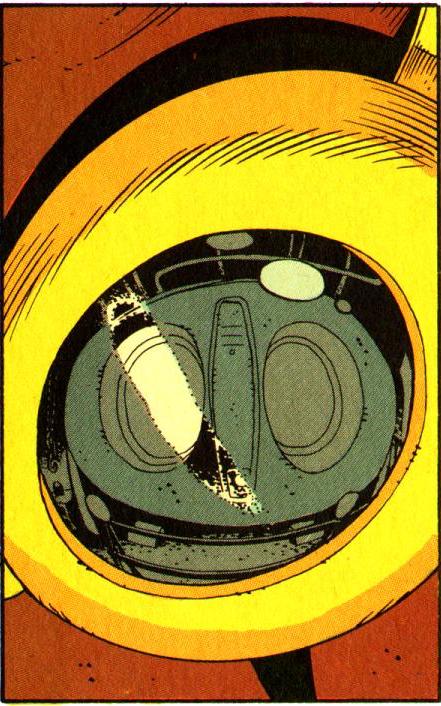

Moore’s disorientation and confusion in the wake of Watchmen is wholly understandable. Even reading Watchmen is, at times, enough to generate a sense of dazed exhaustion. And this is very much the point – an effect consciously generated by Moore’s use of the dense uniformity of the nine-panel grid. As Kieron Gillen puts it in Kieron Gillen Talks Watchmen, “if we’re talking about the many icons of Watchmen, [the nine-panel grid] is the invisible one. It underlies everything. We’re to watch these little boxes – hundreds of them – and make sense by combining them all into a larger piece of meaning. Watch,” he says, and snaps his fingers to cue his projectionist to advance his PowerPoint to a shot of Ozymandias watching his wall of television screens. Gillen talks about the comic as a “clockwork machine” in which “everything is predetermined. The forces that are put into motion mean this… the clock will carry on ticking, and if you read Watchmen enough you’ll know what the next tick is.” Gillen, here, is talking about the comic’s famously ambiguous ending, making a strong case that in fact there is only one possible “next step” for the book to take, and that the inevitable momentum of that step hangs impermeably over the entire work, which is in turn what Morrison speaks of when he talks about how the god of Watchmen is always shoving his cock in the reader’s face.