The Proverbs of Hell 36/39: And The Woman Clothed In Sun

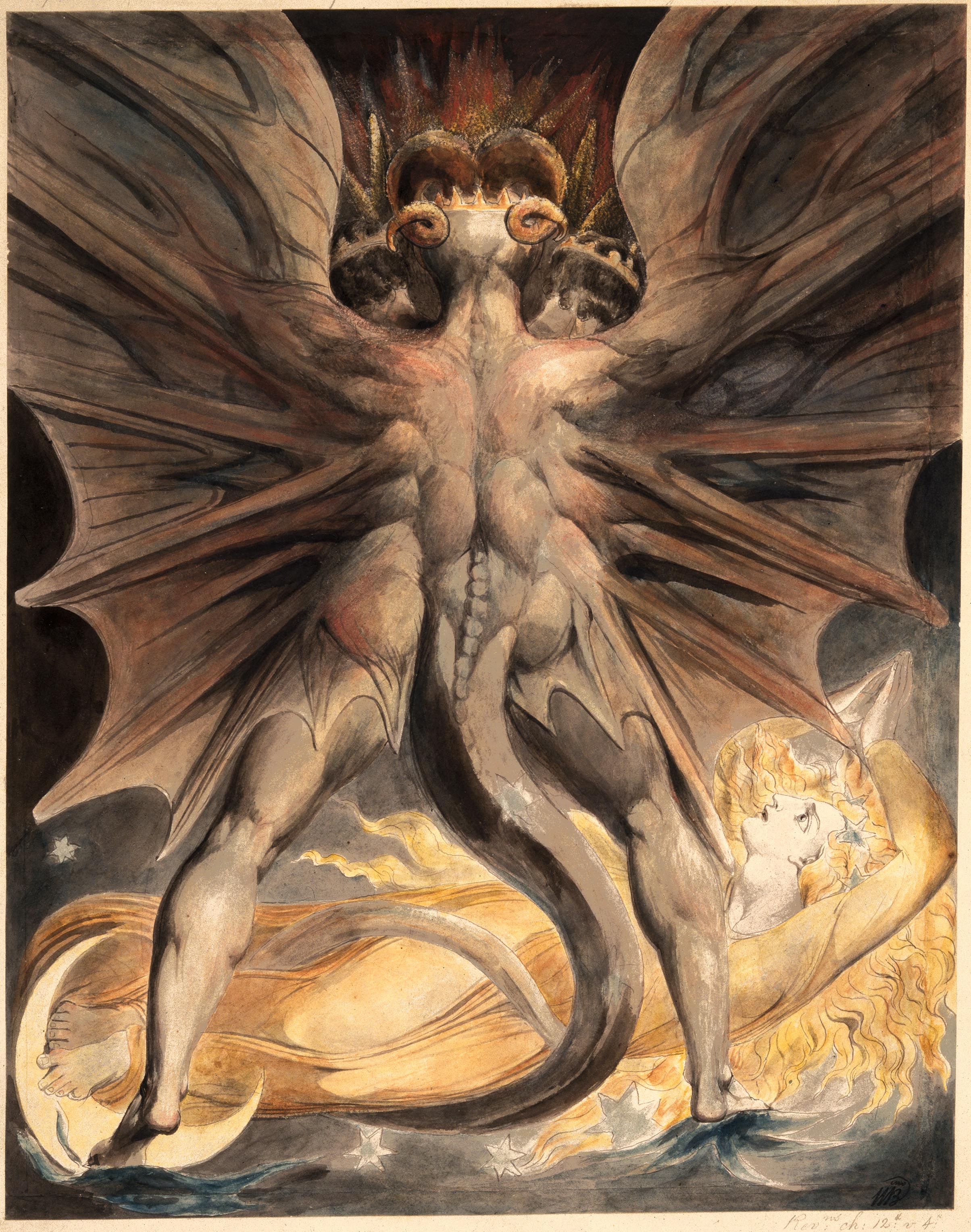

AND THE WOMAN CLOTHED IN SUN: The big one. Hannibal describes its “unique and nightmarish charge of demonic sexuality,” which is fair enough, but seems desperately insufficient. Let’s add, then, a brief discussion of gaze. As John Berger memorably simplifies it, in art the norm is that “men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” Which at least broadly describes this picture, sure, in that we are seeing a woman being looked at. But the woman is obscured in the picture. We watch her being looked at, yes, but we do not really see her ourselves. That picture is The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed With the Sun. Here the object of our gaze is, as they say, dat ass. This isn’t so much a charge of demonic sexuality as a stunningly homoerotic vision of erotic puissance. Dolarhyde, clearly, does not miss the point nearly so much.

AND THE WOMAN CLOTHED IN SUN: The big one. Hannibal describes its “unique and nightmarish charge of demonic sexuality,” which is fair enough, but seems desperately insufficient. Let’s add, then, a brief discussion of gaze. As John Berger memorably simplifies it, in art the norm is that “men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” Which at least broadly describes this picture, sure, in that we are seeing a woman being looked at. But the woman is obscured in the picture. We watch her being looked at, yes, but we do not really see her ourselves. That picture is The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed With the Sun. Here the object of our gaze is, as they say, dat ass. This isn’t so much a charge of demonic sexuality as a stunningly homoerotic vision of erotic puissance. Dolarhyde, clearly, does not miss the point nearly so much.

FRANCIS DOLARHYDE: Hello, Dr. Lecter. As an avid fan, I wanted to tell you I’m delighted that you have taken an interest in me. I don’t believe you’d tell them who I am, even if you knew.

HANNIBAL: What particular body you currently occupy is trivia.

FRANCIS DOLARHYDE: The important thing is what I am Becoming. I know that you alone can understand this.

HANNIBAL: Tell me. What are you becoming?

FRANCIS DOLARHYDE: The Great Red Dragon.

Hannibal’s initial response to Dolarhyde is interesting, in that there’s no obvious piece of information on which he should be able to base this leap. And it’s clearly a massive leap—a response that immediately affirms and reinforces Dolarhyde’s trust in him, but that in no way follows from anything in Dolarhyde’s opening line. (In Harris’s original, the line is Dolarhyde’s.) The easiest explanation is that it has been inferred from the crime scenes; that Hannibal can read a theme of transformation into the particular mutilation and mirrors involved. But the underlying reasoning is never explicated.

The puzzled fascination with which Dolarhyde observes himself talking to Hannibal is an interesting grace note picking up off of his dual nature. The scene has a light tension as to which Dolarhyde is which aspect of him. This is eventually resolved such that the Dolarhyde watching is human, whereas the one talking to Lecter is the Dragon, but the tension is a delicious disorientation.

FRANCIS DOLARHYDE: I want to be recognized by you.

HANNIBAL: As John the Baptist recognized the one who came after.

FRANCIS DOLARHYDE: I want to sit before you as the Dragon sat before 666 in Revelation. I have things I’d love to show you. Someday, if circumstances permit, I would like to meet you and watch you meld with the strength of the Dragon.

HANNIBAL: See how magnificent you are. “Did he who made the Lamb make thee?”

One reacts, of course, with a certain irritation at the banality of invoking “The Tyger” in the vicinity of Blake. It has nothing to do with the Great Red Dragon paintings, which were painted a decade after Songs of Experience, and feels like going for the most obvious bit of Blake instead of building up anything that actually engages with his work.…

Let’s be cheeky and try to understand something about the Austrian School using the ideas of the Frankfurt School. The two are, in any case, now permanently locked-together in a Reichenbachian struggle. At least, the bastard ideological descendants of the Austrian School seem to imagine this. For some reason. So fuck it, let’s ignore the fact that this is actually a delusional notion (at least as it is generally meant), and see what happens when they actually fight.

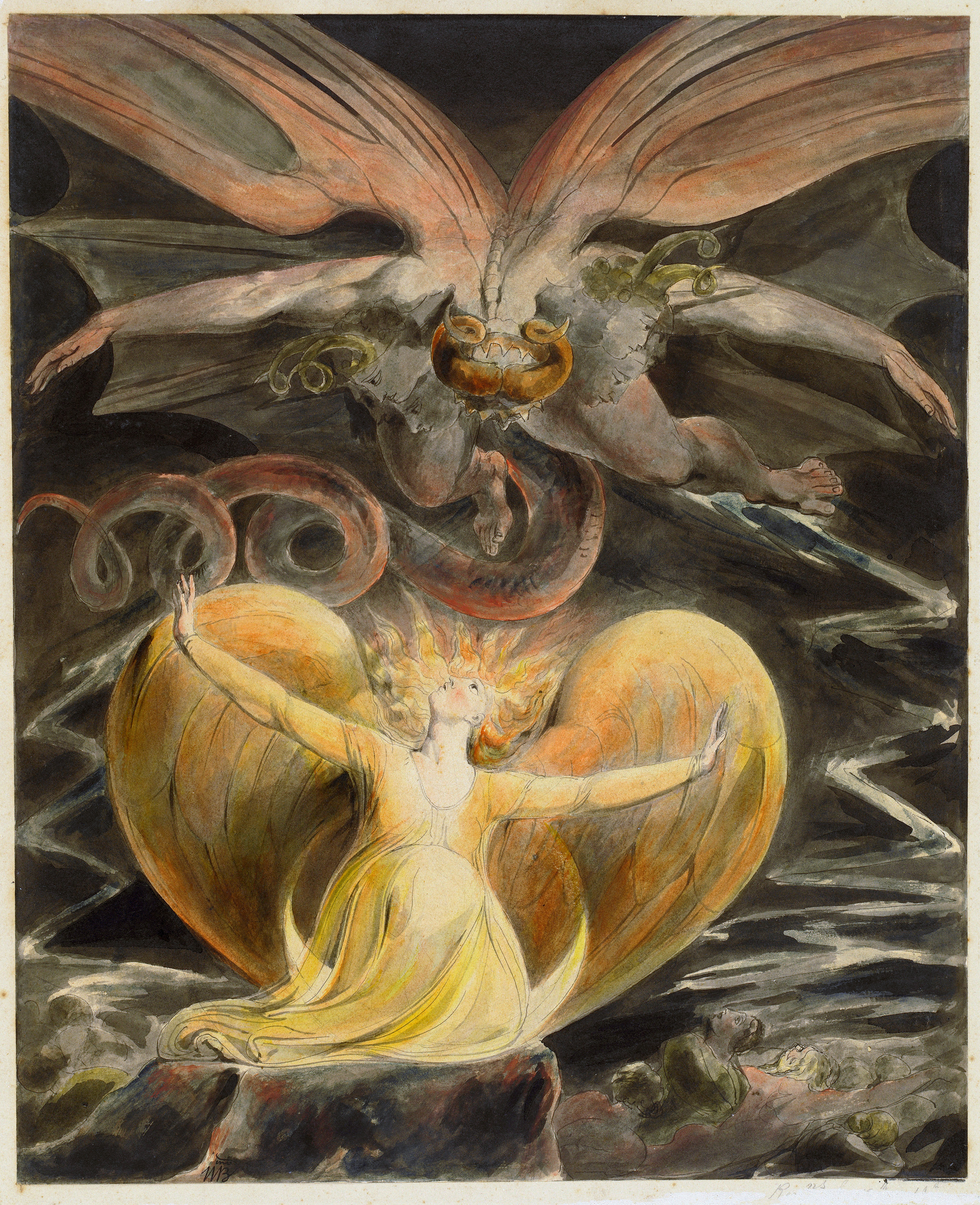

Let’s be cheeky and try to understand something about the Austrian School using the ideas of the Frankfurt School. The two are, in any case, now permanently locked-together in a Reichenbachian struggle. At least, the bastard ideological descendants of the Austrian School seem to imagine this. For some reason. So fuck it, let’s ignore the fact that this is actually a delusional notion (at least as it is generally meant), and see what happens when they actually fight. AND THE WOMAN CLOTHED WITH THE SUN: This is not the picture that Dolarhyde worships, which is “The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed in Sun.” The distinction flummoxed Harris himself, who got the wrong one in Red Dragon, and the most satisfying explanation for this preceding the episode named after the story’s central painting is that Fuller is providing an homage to the error. In any case, this painting is essentially Dolarhyde’s from the opposite perspective. The result is that the woman is the central object of the painting, with the Dragon looming above her, mimicking our own act of looking at her. The picture Dolarhyde prefers is on the whole the far more interesting framing, which we’ll get to next week.

AND THE WOMAN CLOTHED WITH THE SUN: This is not the picture that Dolarhyde worships, which is “The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed in Sun.” The distinction flummoxed Harris himself, who got the wrong one in Red Dragon, and the most satisfying explanation for this preceding the episode named after the story’s central painting is that Fuller is providing an homage to the error. In any case, this painting is essentially Dolarhyde’s from the opposite perspective. The result is that the woman is the central object of the painting, with the Dragon looming above her, mimicking our own act of looking at her. The picture Dolarhyde prefers is on the whole the far more interesting framing, which we’ll get to next week. In his researches into Hayek’s role in the decision to hold the 1981 conference of the Mont Pèlerin Society (MPS) in Pinochet’s Chile, Corey Robin discovered a 1979 letter from Hayek to another MPS member in which he enthusiastically – and, as it transpires, successfully – endorsed Madrid as a conference venue.

In his researches into Hayek’s role in the decision to hold the 1981 conference of the Mont Pèlerin Society (MPS) in Pinochet’s Chile, Corey Robin discovered a 1979 letter from Hayek to another MPS member in which he enthusiastically – and, as it transpires, successfully – endorsed Madrid as a conference venue.  Eruditorum Press is pleased to announce the launch of our latest Kickstarter, for TARDIS Eruditorum Volume 7: Sylvester McCoy.

Eruditorum Press is pleased to announce the launch of our latest Kickstarter, for TARDIS Eruditorum Volume 7: Sylvester McCoy.