The Proverbs of Hell 36/39: And The Woman Clothed In Sun

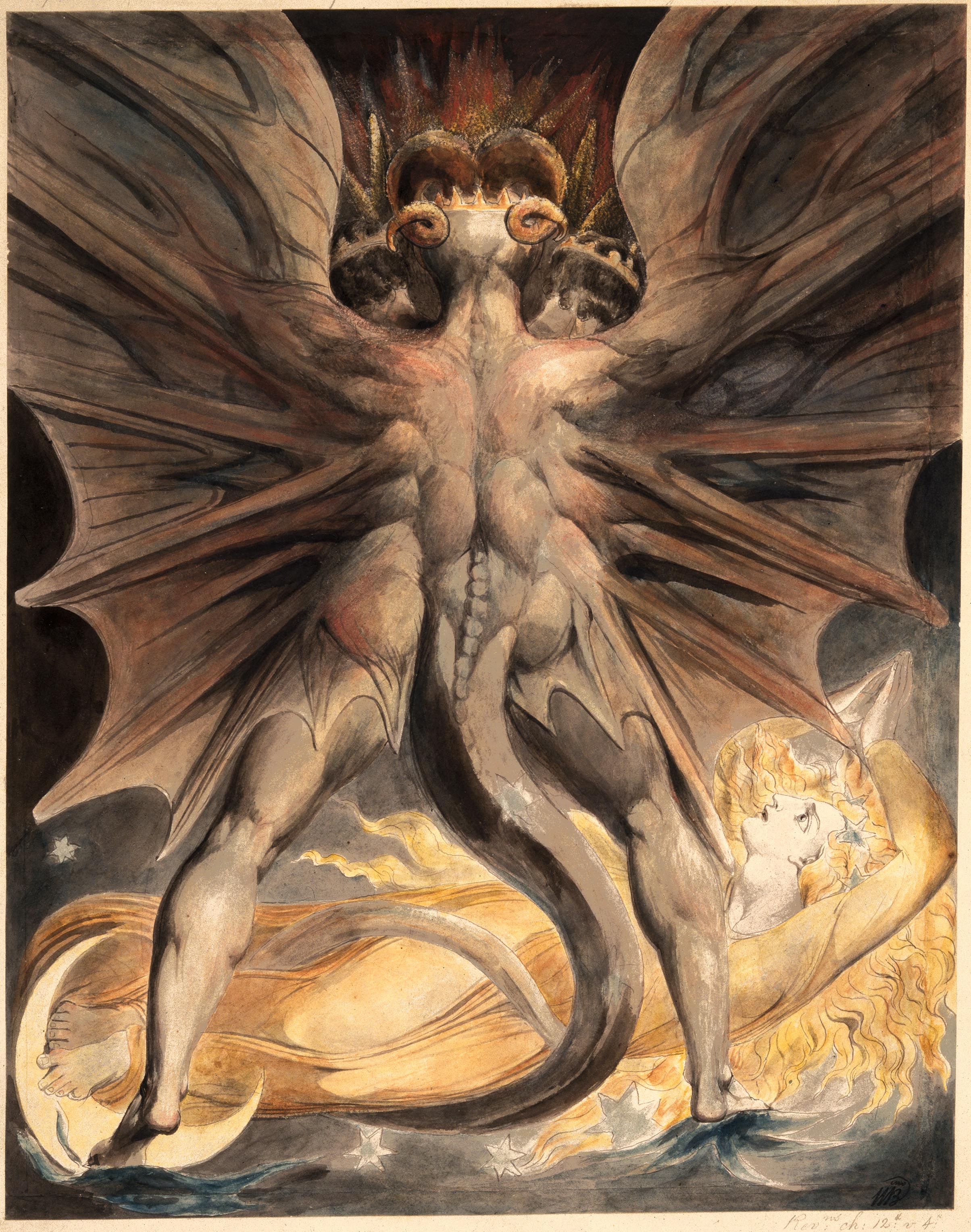

AND THE WOMAN CLOTHED IN SUN: The big one. Hannibal describes its “unique and nightmarish charge of demonic sexuality,” which is fair enough, but seems desperately insufficient. Let’s add, then, a brief discussion of gaze. As John Berger memorably simplifies it, in art the norm is that “men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” Which at least broadly describes this picture, sure, in that we are seeing a woman being looked at. But the woman is obscured in the picture. We watch her being looked at, yes, but we do not really see her ourselves. That picture is The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed With the Sun. Here the object of our gaze is, as they say, dat ass. This isn’t so much a charge of demonic sexuality as a stunningly homoerotic vision of erotic puissance. Dolarhyde, clearly, does not miss the point nearly so much.

AND THE WOMAN CLOTHED IN SUN: The big one. Hannibal describes its “unique and nightmarish charge of demonic sexuality,” which is fair enough, but seems desperately insufficient. Let’s add, then, a brief discussion of gaze. As John Berger memorably simplifies it, in art the norm is that “men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” Which at least broadly describes this picture, sure, in that we are seeing a woman being looked at. But the woman is obscured in the picture. We watch her being looked at, yes, but we do not really see her ourselves. That picture is The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed With the Sun. Here the object of our gaze is, as they say, dat ass. This isn’t so much a charge of demonic sexuality as a stunningly homoerotic vision of erotic puissance. Dolarhyde, clearly, does not miss the point nearly so much.

FRANCIS DOLARHYDE: Hello, Dr. Lecter. As an avid fan, I wanted to tell you I’m delighted that you have taken an interest in me. I don’t believe you’d tell them who I am, even if you knew.

HANNIBAL: What particular body you currently occupy is trivia.

FRANCIS DOLARHYDE: The important thing is what I am Becoming. I know that you alone can understand this.

HANNIBAL: Tell me. What are you becoming?

FRANCIS DOLARHYDE: The Great Red Dragon.

Hannibal’s initial response to Dolarhyde is interesting, in that there’s no obvious piece of information on which he should be able to base this leap. And it’s clearly a massive leap—a response that immediately affirms and reinforces Dolarhyde’s trust in him, but that in no way follows from anything in Dolarhyde’s opening line. (In Harris’s original, the line is Dolarhyde’s.) The easiest explanation is that it has been inferred from the crime scenes; that Hannibal can read a theme of transformation into the particular mutilation and mirrors involved. But the underlying reasoning is never explicated.

The puzzled fascination with which Dolarhyde observes himself talking to Hannibal is an interesting grace note picking up off of his dual nature. The scene has a light tension as to which Dolarhyde is which aspect of him. This is eventually resolved such that the Dolarhyde watching is human, whereas the one talking to Lecter is the Dragon, but the tension is a delicious disorientation.

FRANCIS DOLARHYDE: I want to be recognized by you.

HANNIBAL: As John the Baptist recognized the one who came after.

FRANCIS DOLARHYDE: I want to sit before you as the Dragon sat before 666 in Revelation. I have things I’d love to show you. Someday, if circumstances permit, I would like to meet you and watch you meld with the strength of the Dragon.

HANNIBAL: See how magnificent you are. “Did he who made the Lamb make thee?”

One reacts, of course, with a certain irritation at the banality of invoking “The Tyger” in the vicinity of Blake. It has nothing to do with the Great Red Dragon paintings, which were painted a decade after Songs of Experience, and feels like going for the most obvious bit of Blake instead of building up anything that actually engages with his work. (Contrast with the reasonably adept reading of Dante in “Antipasto,” although to be fair this was borrowed from the novel.) There are, however, two marginal justifications. First, this is situated in the same episode as the literal tiger. Second, Blake’s The Number of the Beast is 666, which is visually quoted immediately after this exchange, does in fact feature a lamb, although this detail is omitted in the show’s representation. More on that painting in two episodes, however.

The sense of artistic laziness is not assuaged by the random and mostly unmotivated invocation of The Garden of Earthly Delights as a backdrop for Bedelia’s lecture. At least when Hannibal got explicitly framed as Lucifer in “Antipasto” it was a clear signification and a sensible part of his lecture. This appears to be Bedelia talking in a room decorated in Bosch. The implication is that she is sinful and physical? Maybe? No, it’s probably just lazy.

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: Dante was the first to conceive of hell as a planned space. An urban environment. Before Dante, we spoke not of the “Gates of Hell,”

but the “Mouth of Hell.” My journey of damnation began when I was swallowed by the beast.

Bedelia uses Dante’s inversion of hell from being rooted in nature to being rooted in civilization to obscure her own inversion, moving the end of her damnation to the beginning.

WILL GRAHAM: How did you manage to walk away unscarred? I’m covered with scars.

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: I wasn’t myself. You were. Even when you weren’t, you were.

WILL GRAHAM: I wasn’t wearing adequate armor.

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: No. You were naked. Have you been to see him?

WILL GRAHAM: Yes.

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: Haven’t learned anything, have you? Or did you just miss him that much?

WILL GRAHAM: Have you been to see him?

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: I’ve seen enough of him. I was with him behind the veil. You were always on the other side.

Bedelia is the rare—perhaps only—character who can pull this sort of rank on Will when it comes to intimacy with Hannibal. It’s interesting to see her take any sort of moral high ground, however, and to have that largely work. For the most part her post-“Dolce” appearances are part of a major heel turn in which she becomes an unsympathetic and even monstrous figure. We’ll see key examples of that shortly, in fact. But this scene, and the basic fact that she’s played by Gillian Anderson, keep that from being a complete flip, leaving her ambiguous and fascinating for it.

The glow effect applied to the tiger is probably the most interesting detail here, not least for the conceptual dissonance between it and the fact of Reba’s blindness. Although, because I am very cynical about invocations of “The Tyger,” it’s potentially just because it’s burning bright or some shit.

Still. Killer first date. (Shit. I didn’t even mean that joke.)

FRANCIS DOLARHYDE: He’s striking. Orange and black stripes. The orange is so bright, it’s almost bleeding into the air around him. It’s radiant.

I mean, or it could just be literalizing this line of dialogue. I guess.

So obviously I have feels.

Let’s start with the obvious—the fact that this is the second Blake painting visually quoted in the episode, and it’s not named after either of them. In neither case is the visual quote particularly compelling. Blake’s art loses an unsurprising amount when mimicked, and the crisp CGI of the Hannibal representations feels like overly fawning fan-art, meticulously detailed in excess of what is actually communicative.

And yet at the end of the day this is still a sex scene that, at the moment of erotic culmination, cuts to Blake art and expects this to communicate and signify. I am obviously going to go for that, and be profoundly grateful that it exists and was broadcast on network television.

WILL GRAHAM: If he does end up eating you, Bedelia, you’d have it coming.

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: I can’t blame him for doing what evolution has equipped him to do.

WILL GRAHAM: If we just do whatever evolution equipped us to do, then murder and cannibalism are morally acceptable.

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: They are acceptable. To murderers and cannibals. And you.

WILL GRAHAM: And you. You lied, Bedelia. You do that a lot. Why do you do that a lot?

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: I obfuscate. Hannibal was never not my patient. Covert treatment suffers secrecy and disapproval.

It’s a nice touch that Bedelia obfuscates in her response, downplaying the severe ethical issues of covert psychiatric treatment as something that is “suffered.” And, for that matter, in her carefully chosen framing of “obfuscation” as distinct from lying. But more interesting is the suggestion that Hannibal’s pathology is a matter of “evolution,” an interesting case of the frequent implication that Hannibal is a higher form of life (which has increasingly supplanted the supernatural account in the show’s affections, itself a transmutation of hauntology into weirdness) being rendered textual.

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: You experienced a traumatic event you now associate with Dr. Lecter.

NEIL FRANK: I nearly choked to death on my own tongue. And he was indifferent.

WILL GRAHAM: How is one patient worthy of compassion and not another?

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: I’m under no illusions how morally consistent my compassion has been.

Cross-cutting Will and Neil like this equates them in a startling way that undermines assumptions about the power relationship in this scene. We recognize at this point that Neil was by any reasonable standard murdered by Bedelia after being treated as an experiment by both her and Hannibal. This, to be fair, also accurately describes Will, but at this moment, with Will in a position of stability and seeming to investigate Bedelia, the equation is compellingly jarring.

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: You’re walking down the street and you see a wounded bird in the grass. What’s your first thought?

WILL GRAHAM: It’s vulnerable, I want to help it.

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: My first thought is also that it’s vulnerable. Yet I want to crush it. A primal rejection of weakness which is every bit as natural as the nurturing instinct.

Mostly here as setup for the next and more significant exchange, to which it is inexorably linked, but it’s a tremendously evocative exchange in its own right.

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: You’re not a killer. You’re capable of righteous violence because you are compassionate.

WILL GRAHAM: How are you capable?

BEDELIA DU MAURIER: Extreme acts of cruelty require a high degree of empathy.

And here we get the chaser. Superficially the observation is applied to Will, and it makes damning sense. But the real insight is regarding Hannibal, both in terms of his friendship with Will and the nature of his cruelty. Again there’s been progress in the show, moving away from the tedious model of “intelligent psychopath” and towards something entirely different. (This also gets at why Reba does not make Dolarhyde less dangerous.)

This is also probably the line of Hannibal that has aged best politically. It’s really a crucial insight into the nature of much political cruelty, namely that it is very rarely extreme, or indeed anything other than banal. Cruelty can be an exquisite artform. It hardly ever is.

PAULA HARPER: May I ask what you’re researching?

FRANCIS DOLARHYDE: A paper on Butts.

PAULA HARPER: On Thomas Butts? You only see him in footnotes as a patron of Blake’s. Is he interesting?

Yes and no. Relatively little information exists about him, but he appears to have been the one of Blake’s patrons most straightforwardly sympathetic to Blake’s vision, and it’s safe to say that nobody who supported Blake’s work to the extent he did could have been uninteresting. One wonders what looking at The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed In Sun in person contributes to that research, but hey.

It says a lot about me that this scene is much more difficult for me to watch than any of the murders, although to be fair some of what it says is also about how explicitly things are depicted. The detail of destroying the original is straight out of the book, but given the particularly complex relationship between Blake and the basic idea of “originals,” there is something particularly violent about eating one of his. But it’s also just an odd rupture to the logic of Hannibal; an alteration to the world that feels bigger than what is usually allowed within it.

When there was a big auction of Hannibal props a few years ago, two-packs of reproductions of the painting, one in marzipan, were available for quite cheap. I really should have gotten one, along with a blood-splattered cutting board. Oh well.

February 21, 2018 @ 9:10 am

“One wonders what looking at The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed In Sun in person contributes to that research, but hey”.

Interestingly, Dollarhyde doesn’t say “Thomas Butts”. You yourself commented at the beginning on The Great Red Dragon’s ass. There are certainly interesting links to be drawn here between sexual desire and a desire for transformation. As someone who recently started questioning their gender identity, I think the lines between wanting to be with someone and wanting to be like someone get blurred sometimes.

“But it’s also just an odd rupture to the logic of Hannibal”

When I watched it the first time, I thought Dollarhyde eating the painting is his attempt to contain the Dragon. This would certainly mesh with him placing mirrors on the eyes and in the mouth and labia of his victims as a way of blocking the ways through which they could consume him. But judging from the opening conversation between Dollarhyde and Hannibal, the former is still set on becoming the Dragon.

In any case, this speaks to the power the eaten has over the one eating. It would be interesting to see what would happen if Hannibal did eat Will.