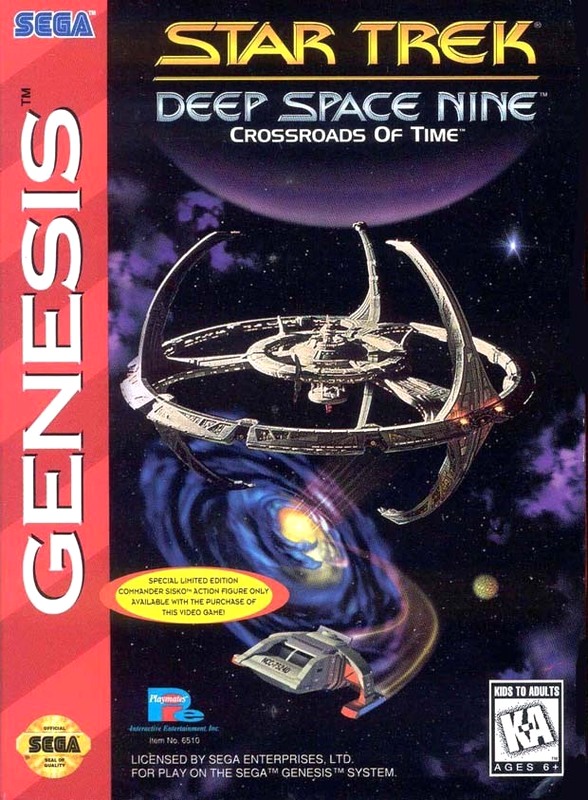

Flight Simulator: Star Trek: Deep Space Nine – Crossroads of Time (SEGA Genesis, Super NES)

While both official and unofficial video games based on Star Trek: The Next Generation were quick to release upon or soon after the show’s premier in 1987 and have been in no short supply over the years (my inability to play almost all of them when they were current notwithstanding), that wasn’t the case for sister show Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. It took a good two and half years after “Emissary” before Commander Sisko and Co. started getting representations in video game form, and when it finally happened it happened a weird way.

While both official and unofficial video games based on Star Trek: The Next Generation were quick to release upon or soon after the show’s premier in 1987 and have been in no short supply over the years (my inability to play almost all of them when they were current notwithstanding), that wasn’t the case for sister show Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. It took a good two and half years after “Emissary” before Commander Sisko and Co. started getting representations in video game form, and when it finally happened it happened a weird way.

Without rehashing the whole history of the video game medium again, it’s perhaps unsurprising that the earliest Star Trek: The Next Generation video games were fanmade or otherwise small-scale affairs for DOS and similar personal computers of the mid-to-late 1980s. The first proper “mainstream” Next Generation game I was aware of (at least, the first on a video game console) didn’t land until 1993 on the Game Boy. There is a very good reason for this, of course: It wasn’t until 1993 that it was eminently clear Star Trek: The Next Generation was a pop culture juggernaut that deserved more recognition than it was getting from tie-ins. 1991 might even have been a more on-point date, but Paramount was slow to capitalize on this and took their time getting their marketing gears in action and doubling down on quality control and brand uniformity. By the time all was said and done of course Star Trek: Deep Space Nine was out, but it didn’t get a companion release.

Of course, there certainly wasn’t a *complete* dearth of merchandise before 1993. The Playmates Toys line launched in 1992, and its quality and speed make a good case for it being the definitive Star Trek: The Next Generation tie-in. And yet even so, it is fundamentally bizarre that they should be the ones to self-publish the first Star Trek: Deep Space Nine video game: Crossroads of Time on the SEGA Genesis and Super Nintendo Entertainment System. Let me make something perfectly clear for those of you who are not versed in the history of the video game industry: A toy company spontaneously deciding to start a video game publishing house is not a normal thing. Sure, it’s happened before-Bandai-Namco is still around, but Namco was, you know, an actual game developer. Mattel and Coleco both made halfhearted stabs at competing with the Atari 2600 in the early 80s, but the current status of those companies gives you an idea of how well that worked out for them. The one notable exception is, of course, Nintendo, who, for a good 70+ years or so was known almost exclusively for their hanafuda playing cards until then-president Hiroshi Yamauchi decided to aggressively expanded into other markets, namely video games.

(It is also perhaps interesting to note how Star Trek: The Next Generation‘s first games went straight to DOS, while Deep Space Nine‘s went straight to home consoles. I think that says something about where the presumed audience was at that point in time.)…

COQUILLES: Coquilles are shells, referring either to shellfish like oysters or to casseroles served in a shell-shaped dish. The poetic meaning would involve something about how people are just shells for the higher angelic spirit within. The crass (and likely intended) meaning is a visual pun based on what happens when you flay wings off of someone’s back.

COQUILLES: Coquilles are shells, referring either to shellfish like oysters or to casseroles served in a shell-shaped dish. The poetic meaning would involve something about how people are just shells for the higher angelic spirit within. The crass (and likely intended) meaning is a visual pun based on what happens when you flay wings off of someone’s back. You were supposed to be getting another Shabcast – with another great guest – this week, but life had other plans. So, having staked everything on that, I am left without an essay to post. So you’ll have to make do with the third chapter of one of the novels I’m currently occasionally writing. Here are chapters

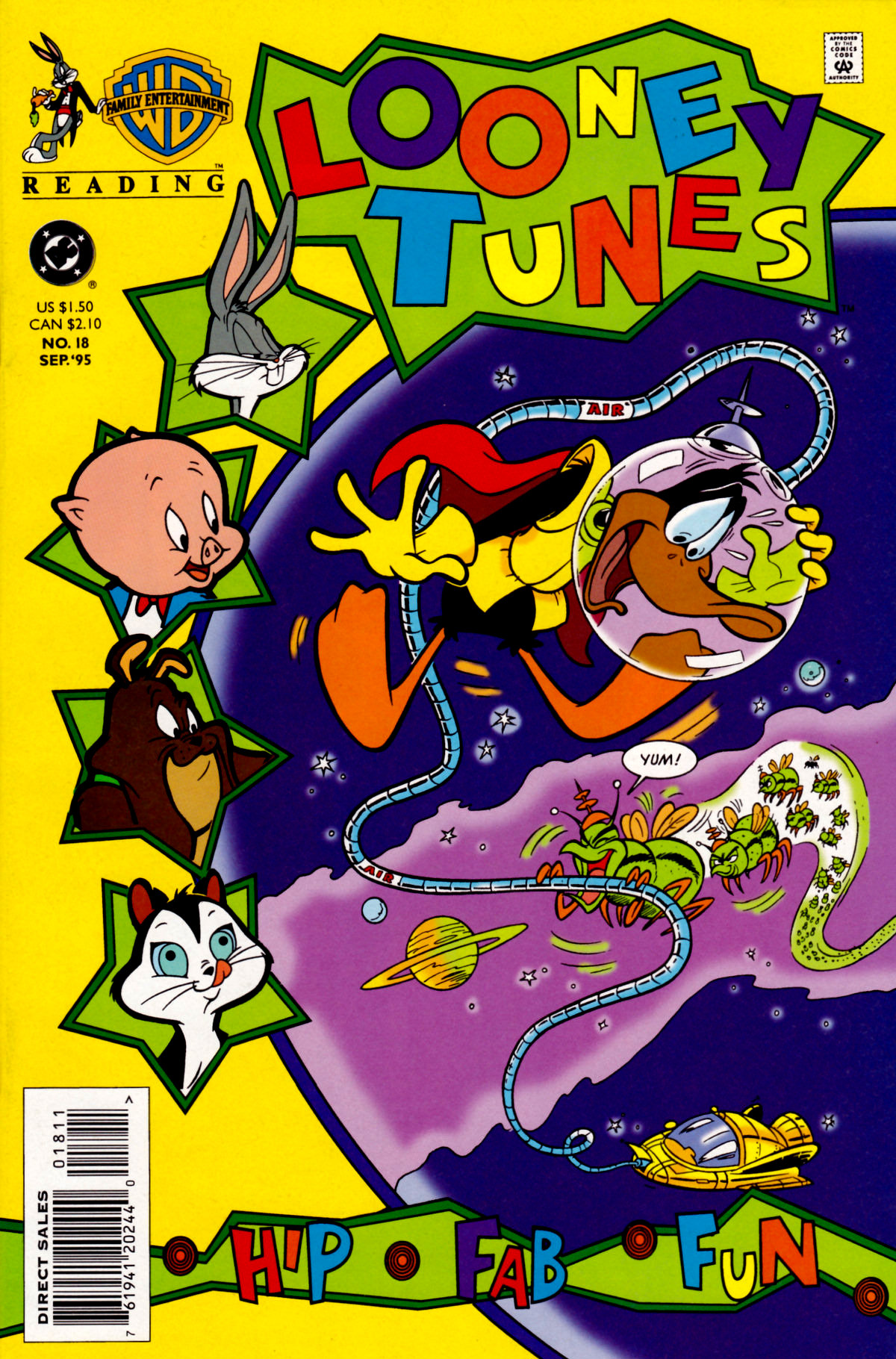

You were supposed to be getting another Shabcast – with another great guest – this week, but life had other plans. So, having staked everything on that, I am left without an essay to post. So you’ll have to make do with the third chapter of one of the novels I’m currently occasionally writing. Here are chapters  I’ve said before I’m no expert on comic books. I know I’ve spent basically the whole back half of this book talking almost exclusively about Star Trek comics, but Star Trek was an exception for me, like it was in a lot of other ways. My knowledge of the history of the medium and its important events and figures is functional at best, but, like a lot of people I should imagine, I did use to read them every now and again. Now I never read a ton of comics (at least, not US comics), but neither was Star Trek the only thing I followed in four colours at the time. I never read superhero comics (though I was aware of the characters from other media), but aside from Star Trek I did have a few books I kept an eye out for at the newsstand whenever I’d go shopping with my family. Probably unsurprisingly, they were all licensed titles: Archie Comics’ Scooby-Doo series, Gladstone Publishing’s reprints of Carl Barks’ Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge stories, and a monthly book from DC Comics published under the Warner Brothers name based on Looney Tunes.

I’ve said before I’m no expert on comic books. I know I’ve spent basically the whole back half of this book talking almost exclusively about Star Trek comics, but Star Trek was an exception for me, like it was in a lot of other ways. My knowledge of the history of the medium and its important events and figures is functional at best, but, like a lot of people I should imagine, I did use to read them every now and again. Now I never read a ton of comics (at least, not US comics), but neither was Star Trek the only thing I followed in four colours at the time. I never read superhero comics (though I was aware of the characters from other media), but aside from Star Trek I did have a few books I kept an eye out for at the newsstand whenever I’d go shopping with my family. Probably unsurprisingly, they were all licensed titles: Archie Comics’ Scooby-Doo series, Gladstone Publishing’s reprints of Carl Barks’ Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge stories, and a monthly book from DC Comics published under the Warner Brothers name based on Looney Tunes.