new forms of labyrinths made possible by modern techniques of construction

new forms of labyrinths made possible by modern techniques of construction

The brutalist architecture that High-Rise does not critique has many fathers (and essentially no mothers), but its Anthony Royal figure is no doubt Le Corbusier, the pseudonym of Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, whose 1923 manifesto Vers Une Architecture (first published in English as Towards a New Architecture, but these days called simply Toward an Architecture) laid out the principles of a new, sleek modernist style, and whose Unité d’Habitation design, used as the blueprint for several 1950s housing projects, defined the specifically brutalist style with its use of rough (or, in French, brut) concrete.

As an architect, Le Corbusier is a giant. Whatever crimes may be laid at the feet of the movement he spawned (and there are many), his actual buildings were iconoclastic and compelling, and remain striking to this day. But it is in many ways as a polemicist that he really shines. Modernism produced no shortage of manifestos, but any list of the great ones that excludes Vers Une Architecture is simply off its head. It is a work of masterful provocation, full of taunting and grandiose slogans. The most famous of these, and thus, given the nature of Le Corbusier’s impact, the most important is his declaration about a third of the way into the book that “a house is a machine for living in.” Ballard echoes it, almost certainly consciously, in the first chapter of High-Rise when he describes the building as “a huge machine designed to serve, not the collective body of tenants, but the individual resident in isolation. Its staff of air-conditioning conduits, elevators, garbage-disposal chutes and electrical-switching systems provided a never-failing supply of care and attention,” a litany that echoes Corbusier’s next sentence, “Baths, sun, hot water, cold water, controlled temperature, food conservation, hygiene, beauty through proportion.”

But the Ballard quote quietly embeds the critique of Le Corbusier when it notes the distinction between serving the collective residents of the building and the isolated individual. At first glance, this is counterintuitive. Even before his turn towards the harsh greys of raw concrete, Corbusier’s aesthetic had a clear austerity to it that’s implicit in the cold inhumanity of the word “machine.” (Note Ballard’s subsequent use of it to describe how people like Laing “thrived like an advanced species of machine” in the high-rise, and for that matter Corbusier’s own praise for men who are “intelligent, coolheaded, and calm” and in touch with their “mechanical side.”) Indeed, the declaration comes in the course of a three-part essay in which he admires the construction of ocean liners, airplanes, and automobiles, praising the uniform principles of their design across multiple manufacturers, their forms standardized by the needs of the clearly stated problem they solve. The statement “a house is a machine for living in” is, for Le Corbusier, essentially equivalent to the observation that the form of an airplane is not that of “a bird or a dragonfly, but a machine for flying.” He praises at length the long and uniform promenades of ocean liners, describing them as “pure, crisp, clear, clean.”…

But the Ballard quote quietly embeds the critique of Le Corbusier when it notes the distinction between serving the collective residents of the building and the isolated individual. At first glance, this is counterintuitive. Even before his turn towards the harsh greys of raw concrete, Corbusier’s aesthetic had a clear austerity to it that’s implicit in the cold inhumanity of the word “machine.” (Note Ballard’s subsequent use of it to describe how people like Laing “thrived like an advanced species of machine” in the high-rise, and for that matter Corbusier’s own praise for men who are “intelligent, coolheaded, and calm” and in touch with their “mechanical side.”) Indeed, the declaration comes in the course of a three-part essay in which he admires the construction of ocean liners, airplanes, and automobiles, praising the uniform principles of their design across multiple manufacturers, their forms standardized by the needs of the clearly stated problem they solve. The statement “a house is a machine for living in” is, for Le Corbusier, essentially equivalent to the observation that the form of an airplane is not that of “a bird or a dragonfly, but a machine for flying.” He praises at length the long and uniform promenades of ocean liners, describing them as “pure, crisp, clear, clean.”…

Continue Reading

Title says it all really.

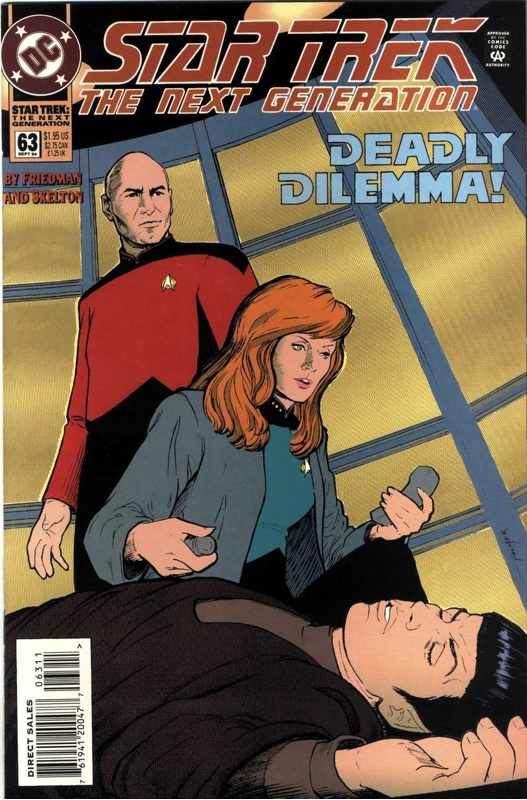

Title says it all really. The Enterprise is on routine patrol of the Romulan Neutral Zone. Perhaps that should be left to speak for itself.

The Enterprise is on routine patrol of the Romulan Neutral Zone. Perhaps that should be left to speak for itself. If you enjoy this and haven’t already, please consider

If you enjoy this and haven’t already, please consider

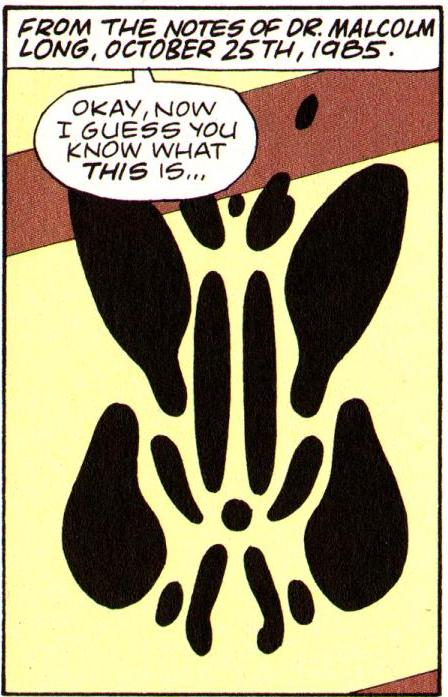

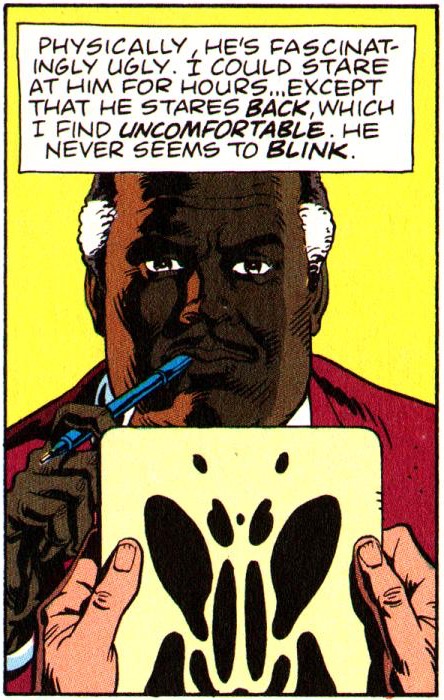

The fundamental problem at the heart of this is simply that Rorschach is an unsettlingly fascinating character. Even Moore, for all the reservations he would come to have about him, freely admits that “Rorschach was one of the characters I enjoyed writing most.” And no wonder – think of a classic line in Watchmen and the odds are overwhelming that you’re thinking of a Rorschach line, probably either a bit of his opening monologue or “none of you understand.…

The fundamental problem at the heart of this is simply that Rorschach is an unsettlingly fascinating character. Even Moore, for all the reservations he would come to have about him, freely admits that “Rorschach was one of the characters I enjoyed writing most.” And no wonder – think of a classic line in Watchmen and the odds are overwhelming that you’re thinking of a Rorschach line, probably either a bit of his opening monologue or “none of you understand.…

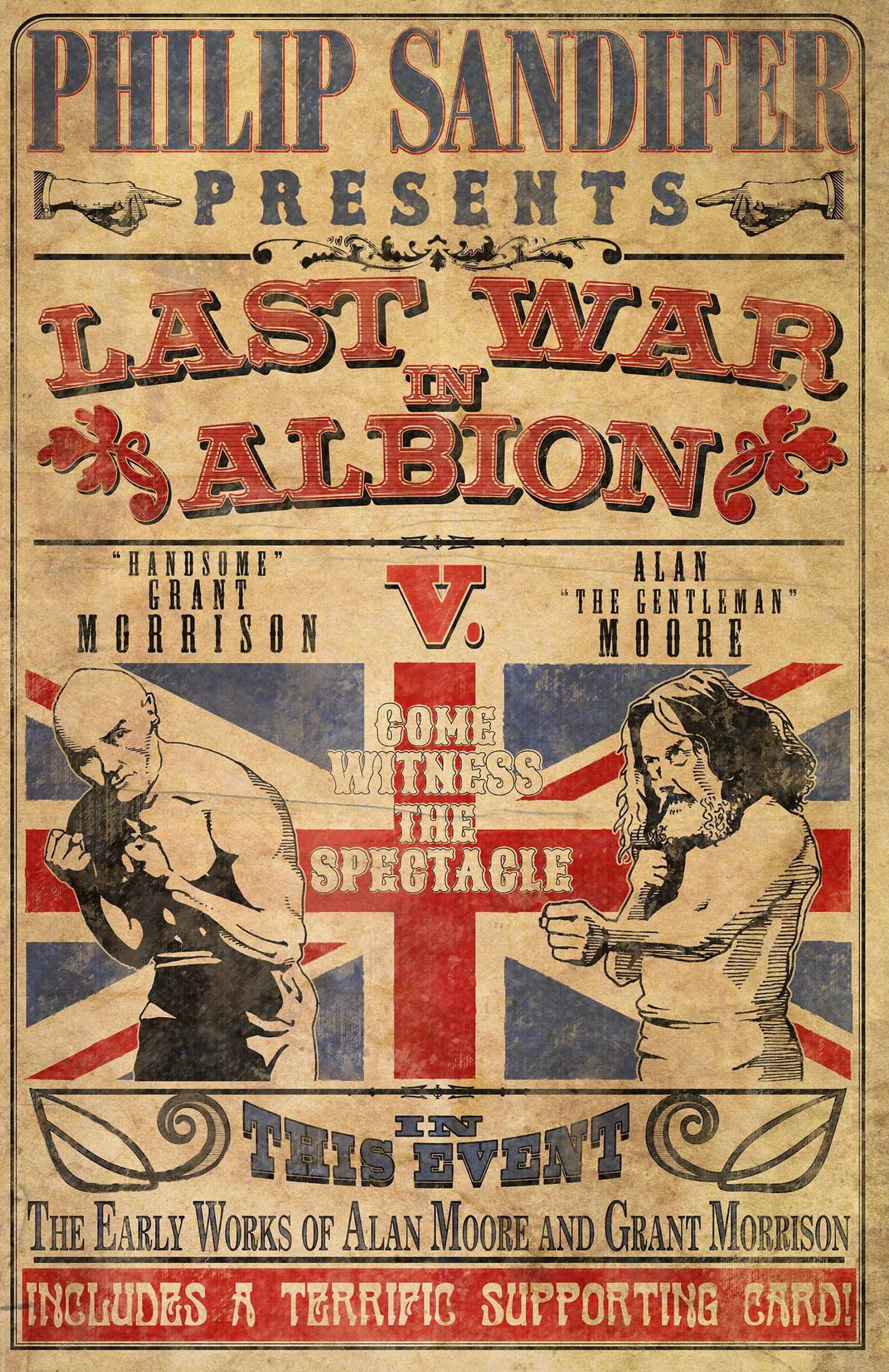

Eruditorum Press is pleased to announce that, at long last, the first volume of The Last War in Albion, Phil Sandifer’s epic critical history of the magical war between Alan Moore and Grant Morrison, is available for purchase. Covering the period from Morrison’s earliest professional sales in 1978 to just before the publication of Watchmen #1 in 1986, the book charts the beginnings of two of the most fascinating careers in the history of comics. The book features extensive looks at Swamp Thing, V For Vendetta, Marvelman, The Ballad of Halo Jones, Captain Britain, and more, including the first detailed study of Morrison’s early superhero strip Captain Clyde since 1985.

Eruditorum Press is pleased to announce that, at long last, the first volume of The Last War in Albion, Phil Sandifer’s epic critical history of the magical war between Alan Moore and Grant Morrison, is available for purchase. Covering the period from Morrison’s earliest professional sales in 1978 to just before the publication of Watchmen #1 in 1986, the book charts the beginnings of two of the most fascinating careers in the history of comics. The book features extensive looks at Swamp Thing, V For Vendetta, Marvelman, The Ballad of Halo Jones, Captain Britain, and more, including the first detailed study of Morrison’s early superhero strip Captain Clyde since 1985.  new forms of labyrinths made possible by modern techniques of construction

new forms of labyrinths made possible by modern techniques of construction But the Ballard quote quietly embeds the critique of Le Corbusier when it notes the distinction between serving the collective residents of the building and the isolated individual. At first glance, this is counterintuitive. Even before his turn towards the harsh greys of raw concrete, Corbusier’s aesthetic had a clear austerity to it that’s implicit in the cold inhumanity of the word “machine.” (Note Ballard’s subsequent use of it to describe how people like Laing “thrived like an advanced species of machine” in the high-rise, and for that matter Corbusier’s own praise for men who are “intelligent, coolheaded, and calm” and in touch with their “mechanical side.”) Indeed, the declaration comes in the course of a three-part essay in which he admires the construction of ocean liners, airplanes, and automobiles, praising the uniform principles of their design across multiple manufacturers, their forms standardized by the needs of the clearly stated problem they solve. The statement “a house is a machine for living in” is, for Le Corbusier, essentially equivalent to the observation that the form of an airplane is not that of “a bird or a dragonfly, but a machine for flying.” He praises at length the long and uniform promenades of ocean liners, describing them as “pure, crisp, clear, clean.”

But the Ballard quote quietly embeds the critique of Le Corbusier when it notes the distinction between serving the collective residents of the building and the isolated individual. At first glance, this is counterintuitive. Even before his turn towards the harsh greys of raw concrete, Corbusier’s aesthetic had a clear austerity to it that’s implicit in the cold inhumanity of the word “machine.” (Note Ballard’s subsequent use of it to describe how people like Laing “thrived like an advanced species of machine” in the high-rise, and for that matter Corbusier’s own praise for men who are “intelligent, coolheaded, and calm” and in touch with their “mechanical side.”) Indeed, the declaration comes in the course of a three-part essay in which he admires the construction of ocean liners, airplanes, and automobiles, praising the uniform principles of their design across multiple manufacturers, their forms standardized by the needs of the clearly stated problem they solve. The statement “a house is a machine for living in” is, for Le Corbusier, essentially equivalent to the observation that the form of an airplane is not that of “a bird or a dragonfly, but a machine for flying.” He praises at length the long and uniform promenades of ocean liners, describing them as “pure, crisp, clear, clean.”