Build High for Happiness 8: Jerusalem (2016)

such rich centers of possibilities and meanings

such rich centers of possibilities and meanings

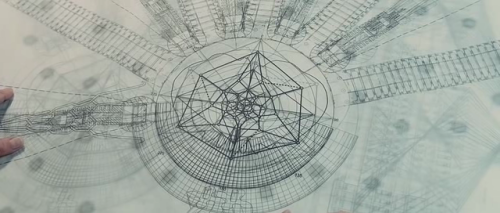

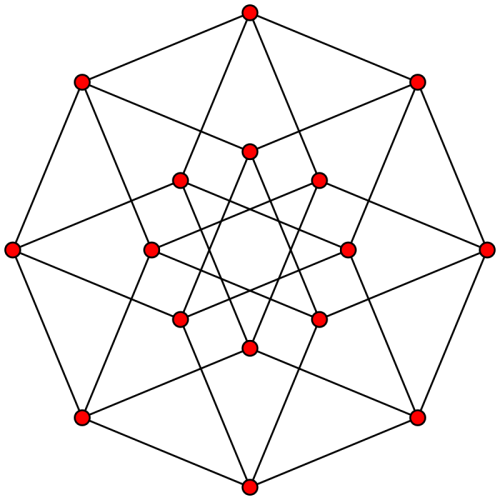

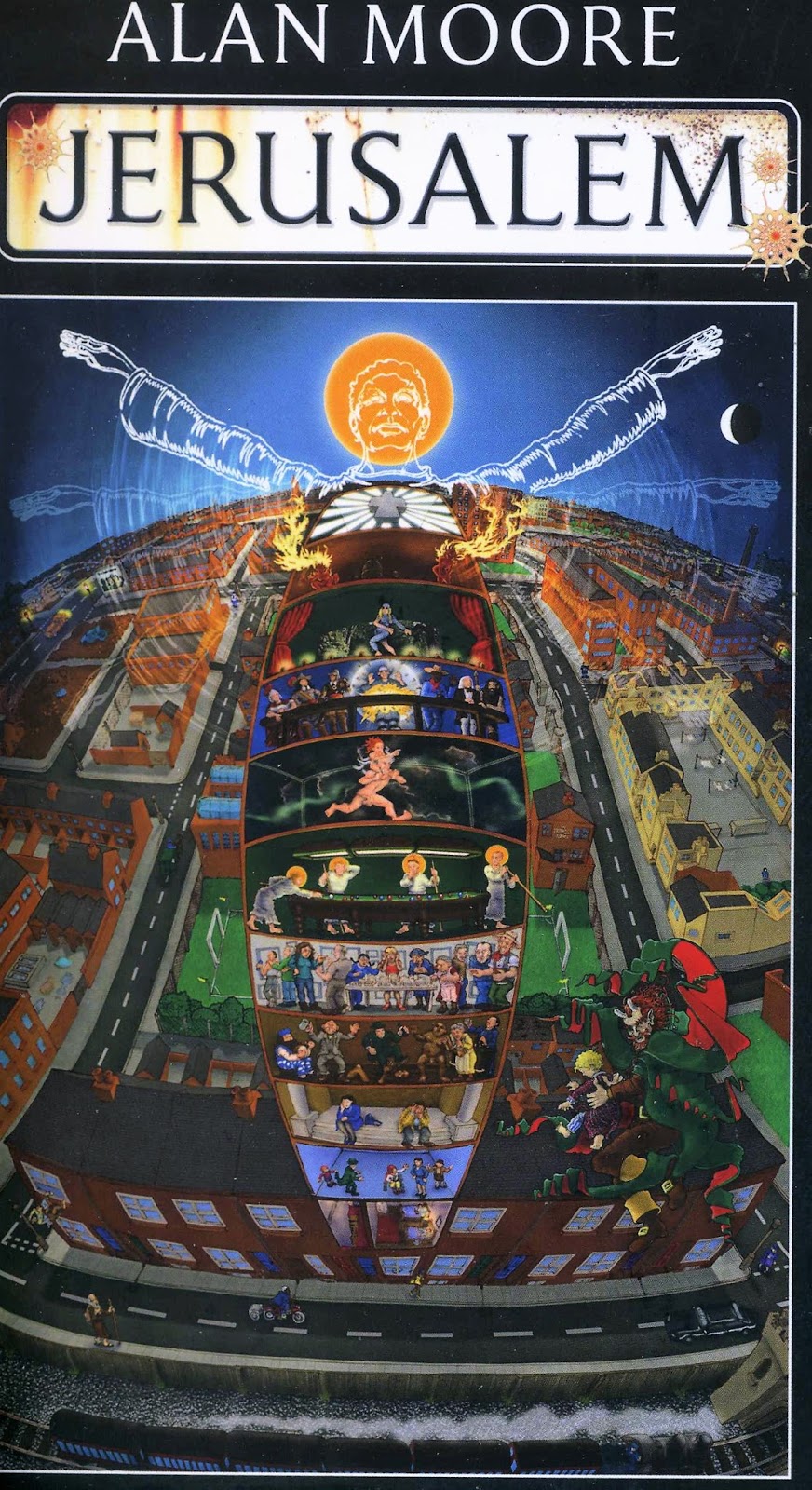

There is of course no other way this could end, which is fitting given that one of the (many) things Jerusalem is about is predestination. Moore’s vision of the world is closely related to the one we’ve been exhaustively exploring throughout this series. He does not actually use the word hypercube (and indeed envisions the structure in even higher dimensions), but it’s nevertheless clearly what’s going on. And though it would be wrong to describe it as a prison (he’s ultimately too optimistic for that), the multidimensional superstructure in which he places us is nevertheless utterly inescapable. As Moore imagines it, reality is a fixed solid existing in at least four dimensions, in which all events are fixed, and human consciousnesses simply experience their lives on endless repeat, passing through their allotted portion of the structure over and over again, experiencing the same unchanging lives each time.

This poses several problems, of which the loss of free will is only one, and a fairly minor one at that. Some are acknowledged by Moore, either within Jerusalem itself or in interviews, most notably the apparent loss of any moral perspective. Moore, being a monstrously intelligent man, anticipates these, emphasizing the sacredness of consciousness and the way that it imposes morality and aesthetics upon the world, and for the most part this works. Certainly there’s a flat truth to it: whatever the overall cosmological structure of reality (or even just history) may be, we are in the end pinned to linearly experienced consciousness, and in a way that means that our perception of morality is all-encompassing. Moore unfolds this with moving humanity, suggesting that we are ourselves harsher moral judges than any external force could ever be, but the point stands as a simple, stark description of how the world works: in the end, we are alone with our experience of it and left to make of that what we will.

Within the novel, of course, this is a cheat, albeit a fairly well-earned one. The narrative perspective shifts among two dozen or so characters in the course of the telling, but they are all in the end Moore’s perspective upon Moore’s world, a fact all but explicitly acknowledged by Moore’s blatant avatar within the work, an artist working on an installation about the working class Northampton neighborhood she lives in that consists of thirty-five works corresponding precisely to the novel’s thirty-five chapters. And the larger cosmology of the novel tacitly acknowledges this cheat: in fact there is an afterlife that one can retire to when one is tired of repeating one’s life, consisting of existence in the higher realm of Mansoul in which the four-dimensional solid of reality can be observed from above, and where the immortal souls appear to have free will and the ability to die. And there are several points where it’s noted that there’s a level above Mansoul on which the pattern repeats, occupied by a singular architect that Moore has been perfectly willing to suggest is him all along, typically via a long and deadpan interview routine in which he discusses the idea of simulationism before noting that the designer would probably incarnate himself in the simulation, and that most portrayals of God are of an older man with a long beard before trailing off pointedly.…

wandering in subterranean catacombs forbidden to the public

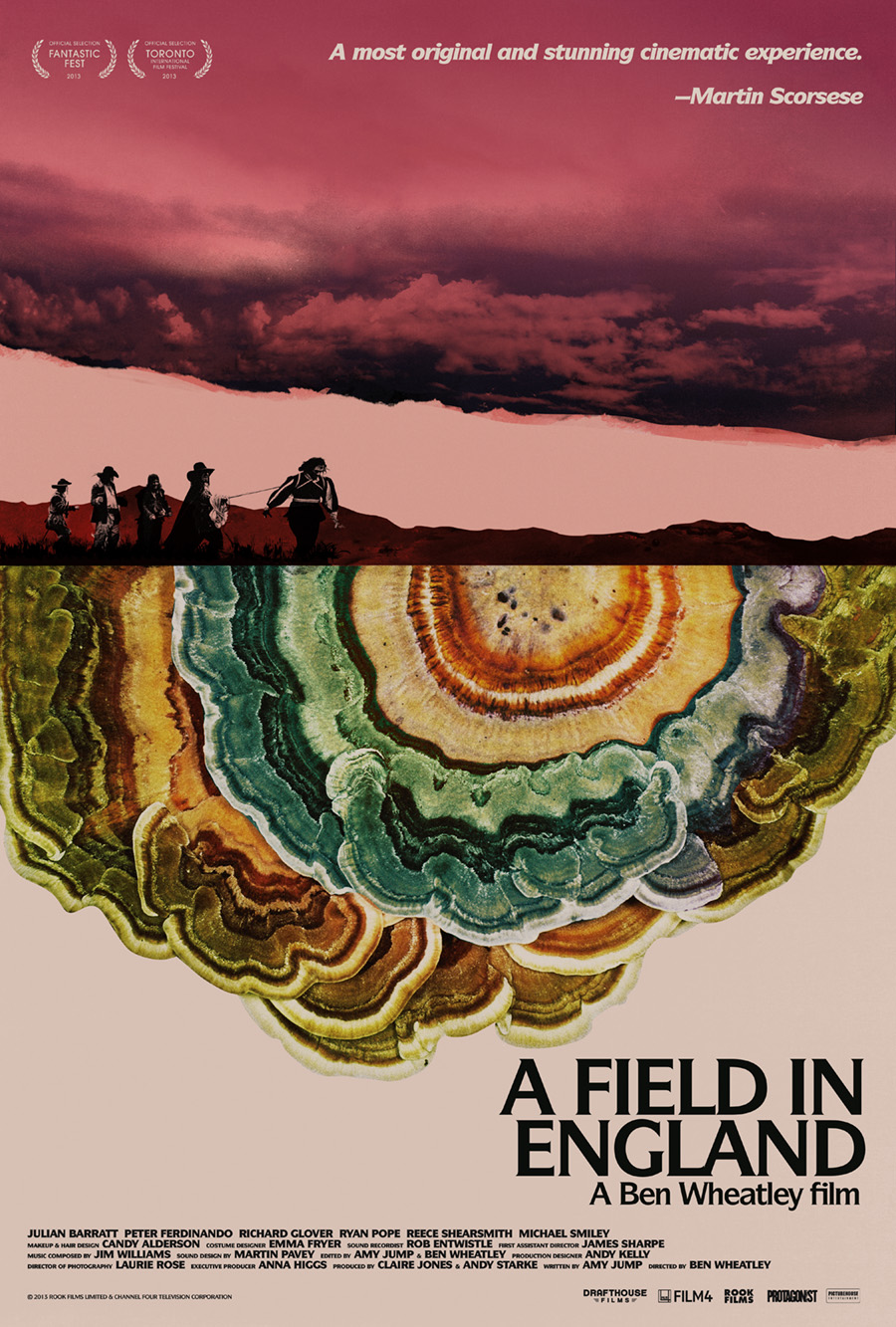

wandering in subterranean catacombs forbidden to the public Wandering in open country is naturally depressing

Wandering in open country is naturally depressing a fixed spatial field entails establishing bases and calculating directions of penetration

a fixed spatial field entails establishing bases and calculating directions of penetration new forms of labyrinths made possible by modern techniques of construction

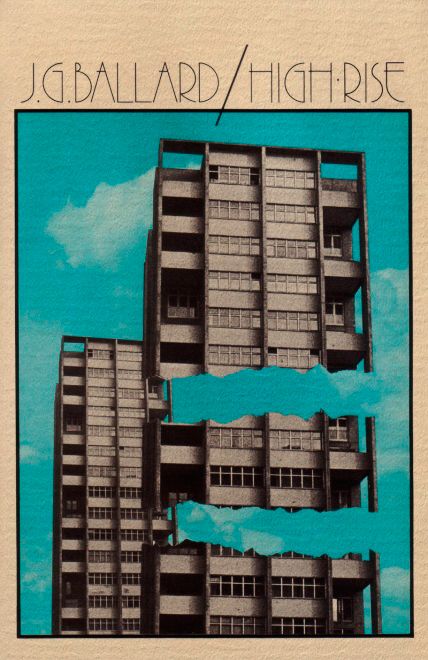

new forms of labyrinths made possible by modern techniques of construction But the Ballard quote quietly embeds the critique of Le Corbusier when it notes the distinction between serving the collective residents of the building and the isolated individual. At first glance, this is counterintuitive. Even before his turn towards the harsh greys of raw concrete, Corbusier’s aesthetic had a clear austerity to it that’s implicit in the cold inhumanity of the word “machine.” (Note Ballard’s subsequent use of it to describe how people like Laing “thrived like an advanced species of machine” in the high-rise, and for that matter Corbusier’s own praise for men who are “intelligent, coolheaded, and calm” and in touch with their “mechanical side.”) Indeed, the declaration comes in the course of a three-part essay in which he admires the construction of ocean liners, airplanes, and automobiles, praising the uniform principles of their design across multiple manufacturers, their forms standardized by the needs of the clearly stated problem they solve. The statement “a house is a machine for living in” is, for Le Corbusier, essentially equivalent to the observation that the form of an airplane is not that of “a bird or a dragonfly, but a machine for flying.” He praises at length the long and uniform promenades of ocean liners, describing them as “pure, crisp, clear, clean.”

But the Ballard quote quietly embeds the critique of Le Corbusier when it notes the distinction between serving the collective residents of the building and the isolated individual. At first glance, this is counterintuitive. Even before his turn towards the harsh greys of raw concrete, Corbusier’s aesthetic had a clear austerity to it that’s implicit in the cold inhumanity of the word “machine.” (Note Ballard’s subsequent use of it to describe how people like Laing “thrived like an advanced species of machine” in the high-rise, and for that matter Corbusier’s own praise for men who are “intelligent, coolheaded, and calm” and in touch with their “mechanical side.”) Indeed, the declaration comes in the course of a three-part essay in which he admires the construction of ocean liners, airplanes, and automobiles, praising the uniform principles of their design across multiple manufacturers, their forms standardized by the needs of the clearly stated problem they solve. The statement “a house is a machine for living in” is, for Le Corbusier, essentially equivalent to the observation that the form of an airplane is not that of “a bird or a dragonfly, but a machine for flying.” He praises at length the long and uniform promenades of ocean liners, describing them as “pure, crisp, clear, clean.” outrage at the fact that anyone’s life can be so pathetically limited

outrage at the fact that anyone’s life can be so pathetically limited ecological analysis of the absolute or relative character of fissures

ecological analysis of the absolute or relative character of fissures a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiences

a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiences