A Brief Treatise on the Rules of Thrones 4.07: Mockingbird

|

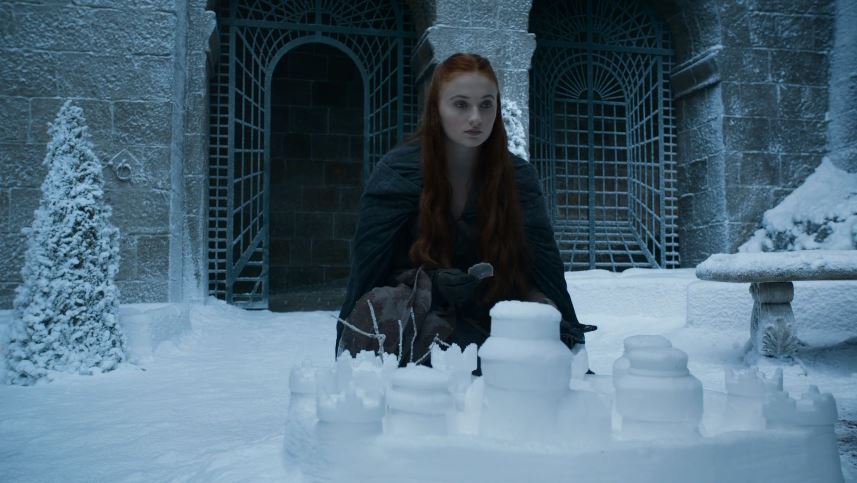

| I think it’s symbolic or something. (The weird doors in the background, I mean.) |

State of Play

The choir goes off. The board is laid out thusly.

Lions of King’s Landing: Tyrion Lannister, Jaime Lannister, Cersei Lannister

Dragons of Meereen: Daenerys Targaryen

Direwolves of the Wall: Jon Snow

The Mockingbird, Petyr Baelish

The Burning Heart, Melisandre

Archers of the Wall: Samwell Tarly

The Direwolf, Sansa Stark

The Direwolf, Arya Stark

The Dogs, Sandor Clegane

The Shield, Brienne of Tarth

Chains of King’s Landing: Bronn

With the Bear of Meereen, Jorah Mormont

Winterfell, the Dreadfort, and Braavos are abandoned.

The episode is in eleven parts. The first runs four minutes and is set in King’s Landing. It is in sections. The first section is three minutes long; the first image is of an angry Jaime, his dialogue preceding his appearance. The second section is one minute long. The transition is by dialogue, from Jaime talking about who Cersei will choose as her champion to the Mountain

The second part runs five minutes and is set in the Riverlands. The transition is by family, from Gregor to Sandor Clegane.

The third runs three minutes and is set at the Wall. The transition is by family, from Arya Stark to Jon Snow.

The fourth part runs four minutes and is set in King’s Landing. The transition is by hard cut, from Jon and Sam sitting ruefully to Tyrion’s window.

The fifth part runs three minutes and is set in Meereen. The transition is by hard cut, from Tyrion in his cell to the great pyramid.

The sixth part runs four minutes and is set in Dragonstone. The transition is by image, from naked Daario to naked Melisandre.

The seventh part runs three minutes and is set in Meereen. The transition is by hard cut, from Melisandre and Selyse looking into the fire to Daario walking out of Daenerys’s room and getting dressed.

The eighth runs three minutes and is set in the Riverlands. The transition is by hard cut, from Daenerys to a wide shot of the Hound and Arya.

The ninth runs five minutes and is also set in the Riverlands. The transition is by dialogue, with Brienne and Podrick coming to speak of Arya.

The tenth runs five minutes and is set in King’s Landing. The transition is by dialogue, with Podrick having just talked about Tyrion.

The last runs eight minutes and is set in the Eyrie. The transition is by family, from Tyrion to Sansa. The final image is of the Moon Door after Lysa Arryn has taken landing on a snake to new levels.

Analysis

Structurally speaking, the elegant style of play that had been the hallmark of the season pretty much gives out here. “Mockingbird” is a jagged mess of hard cuts and piece-shuffling concerned more with positioning plot lines to be able to handle the existence of a single-location ninth episode than with anything of its own. Thankfully the season’s overall shape from “First of His Name” on, in which episodes are anchored by a sequence of escalating set pieces, largely covers for this lack, making “Mockingbird” a more or less satisfying experience.

Given this, any analysis must start at the end, as Lysa Arryn’s return to the story comes to a succinct halt. It is interesting to look back at “The Climb,” in which Littlefinger emphatically bested Varys in the last of their occasional and consistently delightful throne room debates. This season Varys has essentially been a bystander to events, whereas Littlefinger has now had his fingerprints on the two most shocking deaths of the season, as well as being offered as the solution to what was literally the show’s longest standing mystery. The result, especially in the context of the episode title, is to confirm the fundamental shift indicated at the end of “The Climb,” making Littlefinger the apparent architect of the board. (And it’s notable that Varys has had essentially nothing to do all season.)

But notably, his role in Joffrey and Jon Arryn’s deaths were only revealed retrospectively. Here, for the first time since his betrayal of Ned, we finally see Littlefinger in action, and we see that his methods are far from architectural. He makes a significant alteration to the state of play in killing Lysa, yes. Indeed, a case can be made that destabilizing the Vale by killing Lysa is actually a more substantial shift in the balance of power than replacing Joffrey with a more pliable king and thus solidifying Tywin’s control over things. But it’s an utterly impulsive act – an unplanned reaction to momentary circumstances that only exist because of his earlier surrender to his lust. In other words, yes, Littlefinger is the figure most responsible for the current shape of play, but this mostly serves to highlight the way in which events are on the brink of chaos and collapse.

Which they unmistakably are. Or, rather, they mistakably are. Nothing, after all, looks particularly out of the ordinary, although much of this is simply down to Tywin’s unwavering hand, a fact notably pointed out by Davos last week. And yet across the board things are on the brink. Jon is alone in understanding the threat to the Wall. Tyrion, as much the architect of any stability in King’s Landing as Tywin, is all but on death row. Daenerys’s straightforward and unstoppable conquest has given way to precarious rule. And now the Vale joins the North and the Riverlands in having lost their long-standing regimes to chaos.

The next most substantial bit of episode is King’s Landing, which is essentially confined to Tyrion’s cell with a brief sojourn to the wonderfully ludicrous spectacle of the Mountain, apparently only recently arrived in the capital, casually slaughtering people for no discernible reason. The structure here is probably the most elegant thing about the episode, as Tyrion fails to recruit the two most obvious choices for his champion, Jaime because he can’t face the Mountain, Bronn because he won’t, before, as the official description dryly puts it, enlisting an unlikely ally. This is perhaps overstatement given the degree to which Oberyn has been visibly woven into Tyrion’s fate so far, but the scene between them, with Oberyn’s account of visiting Casterly Rock as a child probably being the single best sequence in his brief time on the show.

The rest, however, is varying degrees of mess. The Jon and Daenerys scenes are classic instances of “well we’d better put them in or else people might forget they’re there.” Contriving another instance of Jon conflicting with Alastair is better than leaving him out of the show two weeks in a row, sure, but does nothing. And the Daenerys scene exists largely to give Jorah and Daenerys a sympathetic moment before next week, which is reasonable, but still leaves the scene mostly interesting for Michael Huisman’s ass, the most sexualized a male credited regular ever gets (although Huisman’s not a regular until next season).

The Arya/Hound scenes are predictably more fun, and more straightforward in their use, demonstrating Arya’s growing warmth towards the Hound as she tries to persuade him to let her help him, and providing some (re)-exposition about the suddenly important Gregor Clegane. They also have the typically welcome decision to decompress things a bit, with the scene in which the Hound puts the wounded man out of his misery given the room it needs to breathe despite mostly being important for its mood and tone. But even these are a bit off, the attack by Rorge and Biter given curiously excessive weight in light of the way this plot is eventually going to diverge from its book version. A divergence, speaking of which, that is set up by the episode’s real and self-evident highlight: Hot Pie’s return.

July 12, 2016 @ 1:14 pm

It’s funny how killing Joffrey would have been a perfectly reasonable action for any reasonable person in Littlefinger’s position, but is hard to account for in his case because of his espousal of chaos. That point of view would seem to urge leaving Joffrey in place to tear the Lannister-Tyrell regime apart. No wonder he had to flannel a series of explanations, of increasing plausibility but none of them entirely convincing.

In general, I think the easiest way of making sense of his behaviour is to suppose that it’s as clear to him as it always has been to the audience that he’s protected from on high by the Prince of Darkness (an elderly bearded gentleman with an idiosyncratic taste in headgear), and can do whatever pops into his head because it will all work out for him regardless (at least until the last book/season, when all bets are off for everyone, except maybe Tyrion).

The relevant motto here, from Martin’s perspective at least, is “Shoot all the Greyjoys you want, if you can hit ’em, but remember it’s a sin to kill a Mockingbird”.

Sorry.