A Red and Angry World (Book Three Part 2: Morrison’s Style, The Coyote Gospel)

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Morrison’s first assignment from DC, the biggest in their career, was to revitalize the all but forgotten character of Animal Man, which they set about doing according to a template originated by Moore on Swamp Thing. But this was not the whole story.

There is a red and angry world… red things happen there. The world eats your wife, eats your friends, eats all the things that make you human. And you become a monster. And the world just keeps on eating.—Alan Moore, Swamp Thing

These Moore riffs existed, after all, in a comic where Animal Man treats superheroing as a job to support his family, musing on ways to increase his profile. Joining the Justice League International is mooted as a plausible option, but he reacts to his wife’s suggestion that the Outsiders might be more his speed with horror, saying that they’re “almost as bad as the Forgotten Heroes. I’m trying to get away from all that nohope stuff.” This is both sly metafictional commentary on the order of precedence within the DC Comics line and a clever vision for what superheroing is. Neither of these have any precedence in Moore, whose “superhero as ordinary person” riff in Miraceman never got bogged down in questions like how Michael Moran paid the rent. And they do have analogues in Morrison, who works with similar ideas in Captain Clyde and Zenith.

Similar examples abound. A scene where Animal Man briefly meets a distracted Superman who compliments the big A on his costume before flying off to rescue a plane, a riff where Animal Man signs an autograph for a kid who’s immediately disappointed he’s not Aquaman, and a repeated tendency to entertain himself by giving Animal Man weird powers from random animals instead of, as Dave Wood typically did, finding some excuse to put him near a tiger or something. Morrison even gets a cliffhanger set piece out of this, with Animal Man getting his arm ripped off in a fight and regrowing it with the power of earthworms. (And being Morrison, they then have Animal Man express a degree of confusion and horror at how weird this is.)

Perhaps more to the point, however, while Morrison uses many of Moore’s techniques and approaches, they use them as tools, not as basic modes of operating. Morrison throws in portentous narration, but they’re not as good at it as Moore, never capturing his poetic lilt, and they clearly recognize it, using it purely for Bwana Beast’s narration instead of as a core structural element of entire issues. Morrison writes Berger the Moore riff they know she’s looking for, but the result is clearly Morrison doing Moore as opposed to a Moore imitation with no further character or elements. It is perhaps most impressive against the backdrop of Veitch’s Swamp Thing and Delano’s Hellblazer, managing both to land closer to a successful Moore imitation than either and to more successfully do its own thing. This was no small feat, and it’s not hard to see why DC gave Morrison the go ahead to make the series an ongoing.

For Morrison’s part, if they were going to write the book as an ongoing then they wanted to do more than an Alan Moore riff. Accordingly, they set about doing a series of one-shots that would allow them to redefine the book in their own image. The first and most extraordinary of these was called “The Coyote Gospel.” At its simplest level, this story was a riff on the Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote cartoons from the Looney Tunes/Merrie Melodies stable of animated shorts, which served as a key element of DC’s corporate parent Warner Bros.’ brand identity. Warner Bros., for its part, was founded in the early days of the 20th century by a quartet of Polish immigrant brothers named Wonsal, anglicized to Warner. They began as a theater company, buying a movie theater in New Castle, Pennsylvania in 1903, and gradually expanded to film distribution and production, breaking out with the Rin Tin Tin features in the 1920s.

Their animation unit began as an independent studio created by Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising, who in 1930 sold a cartoon featuring their character Bosko to Leon Schlesinger, who in turn sold it to Warner under the Looney Tunes banner, and, subsequently, the sister series Merrie Melodies. This was an obvious clone of Disney’s Silly Symphonies series, pitched as a means of promoting Warner’s music library. In 1933 Harman and Ising fell out with Schlesinger, who took over the line, hiring directors like Friz Freleng, Tex Avery, and Chuck Jones and creating a run of popular characters beginning with Porky Pig in 1935, Daffy Duck in 1937, and both Elmer Fudd and Bugs Bunny in 1940. This kicked off a twenty year period in which Warners’ shorts were the most popular animated shorts in the industry, during which they debuted Sylvester the Cat, Tweety Bird, Yosemetie Sam, Foghorn Leghorn, and, in 1949, Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner.

These characters were the brainchildren of writer Michael Maltese and director Chuck Jones, who eventually took over writing duties on the series as well. Jones was a proper legend of the animated form, and the Road Runner shorts were in many ways the zenith of his work. Their premise is aggressively simple: Wile E. Coyote tries and fails to catch the Road Runner. Crucially, unlike the conceptually similar shorts in which Bugs Bunny evades hunters like Elmer Fudd his failure is not generally due to any cleverness on the Road Runner’s part (although he occasionally straightforwardly outsmarted the coyote), but because of the collapse of his grandiose schemes, often but not always due to a malfunction in whatever gadget he’s bought from the omnipresent Acme Corporation. (Jones, clearly with the benefit of hindsight, explains this as a metaphor for his own failures using tools.)

Looney Tunes were in general defined by their sense of manic and frenetic energy, but the Road Runner shorts took this to a conceptual limit, spending the bulk of their time as literal blurs of motion. Done entirely without dialogue save for the Road Runner’s incessant, mocking “Beep Beep,” described by Chuck Jones as “the Esperanto of comedy,” the series distilled its form into the absolute purest essence, stripping away everything that was not the basic structure of “the gag.” There is no overarching plot to a Wile E. Coyote/Road Runner cartoon—it is simply a series of doomed efforts on the part of Wile E. Coyote, each of which end with grievous bodily harm that is shrugged off a few seconds later for another try. This was storytelling in its most archetypal sense, less a series of gags than an endless series of facets of a single ur-gag manifesting in self-contradictory simultaneity: there was a Coyote and a Road Runner; they fought, and the Road Runner won. Here are all the ways it happened.

The level of abstraction involved in crafting such as this requires an intense formalism, and indeed Jones codified a set of nine rules governing the construction of Road Runner cartoons. These were almost certainly developed after the fact as opposed to as a design document per se, not least because almost all of them are at some point broken. But their formulation still reveals the amount of structure involved, covering relatively banal issues like the fact that “the Road Runner must stay on the road—otherwise, logically, he would not be called Road Runner” and specifying that all stories must take place in the American desert—and issues that are clearly axiomatic to the function of the cartoons, perhaps most obviously the twin injunctions that “the Road Runner cannot harm the Coyote except by going ‘Beep-Beep!’” and “no outside force can harm the Coyote—only his own ineptitude or the failure of the Acme products.” Perhaps most important, however, was Jones’s account of the Coyote’s psyche, explaining that he “could stop anytime—if he were not a fanatic.”

This simple observation of motive is at the heart of the cartoon’s central structural irony. Although the underlying rules of such things mean that Wile E. Coyote is the bad guy and the Road Runner is the hero, in terms of how the cartoons harness audience sympathy there is no question that the Road Runner is the villain. The central emotional engine of the gag is Wile E. Coyote’s fundamentally doomed quest: his endless, scheming confidence that this time he’ll get it as it fades inevitably to crushing indignity. As Jones puts it, “In the Road Runner cartoons, we hoped to evoke sympathy for the Coyote. It is the basis of the series: the Coyote tries by any means to capture the Road Runner, ostensibly and at first to eat him, but this motive has become beclouded, and it has become, in my mind at least, a question of loss of dignity that forces him to continue. And who is the Coyote’s enemy? Why, the Coyote. The Road Runner has never touched him, never even startled him intentionally beyond coming up behind the Coyote occasionally and going ‘Beep-Beep!’”

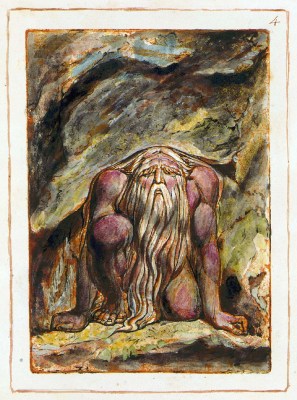

It is akin to Blake’s treatment of Urizen, who is at once a force of destruction and, crucially, a figure of tremendous pity that Blake spent his entire artistic career trying to redeem. Indeed, much of the basic dynamic of the Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote cartoons resembled Blake, whose mythology similarly functioned through an endlessly variant series of independent tellings, each of them exposing new facets of the whole. Like the Coyote, Urizen is a force of hubristic reason within this system, endlessly constructing systems which serve only to ensnare him. Both Urizen and the Coyote are driven primarily by their own inability to stop—by the fact that they simply cannot conceive of any action other than imposing their system onto the world even as doing so brings him to repeated, helpless ruin. They are two sides of the same coin—two images of the demiurge failing utterly to confront the knowledge that there exist things beyond his single vision.

This observation sits at the heart of “The Coyote Gospel,” which uses Wile E. Coyote as a Christ metaphor. It opens with a man and a hitchhiker in an eighteen wheeler. They discuss luck and fate, with the truck driver explaining the history of his silver cross pendant, which he got from his boyfriend Billy. Whilst driving, however, they strike some sort of animal—a doglike creature on its hind legs. As the truck speeds on the comic lingers on the roadkill, which proceeds to begin healing itself while Morrison’s narration describes the excruciating pain as “its pelvic girdle fuses along hairline sutures, to cradle rapidly healing organs. A splintered rib that saws back and forth in one lung is withdrawn. The thoracic case locks seamlessly. The lung reinflates.”And as the creature rises, the narration makes the point clear: “Behold! The miracle of the resurrection!”

From here the story jumps forward a year. The man is now stalking the desert. Narration explains that Billy died in an awful accident, and that the hitchhiker had failed to make it in Holywood, turned to sex work, and been killed in a drug raid. From this the man has concluded that the creature he ran over a year earlier must have been the devil, and he has thus vowed to kill it. And so he stalks the desert with a rifle, laying bombs and preparing to hunt the creature. What follows is a violent and macabre parody of Chuck Jones’s cartoons; the man shoots the creature, who plummets down a ravine. “Briefly, its feet pedal empty air,” and then it slowly recedes down the canyon, leaving nothing but a comedic puff fo dust; meanwhile the narration describes how “an outcrop breaks its spine. A second impact crushes its skull. Unhinges its jaw. Snaps both legs. And it hits bottom, blind and quadriplegic.” Then the man drops a rock on it. After that, the bomb goes off, mangling the creature almost beyond recognition.

As this is going on Animal Man happens by, and the creature proceeds to abandon the now gravely injured man, staggering off to find Animal Man instead and present him with the scroll it has been wearing around its neck all issue. Animal Man opens it, and the comic shifts to provide “the Gospel according to Crafty” over three and a half pages. In these the comic changes to a funny animals style to describe a world where various animals fight in “n endless round of violence and cruelty. With bodies that renewed themselves endlessly, following each wounding, no one thought to challenge the futile brutality of existence. Until Crafty.” Defeated one too many times by his unseen but fast moving adversary, Crafty takes it upon himself to find God, demanding he be held to account for all this cruelty. In response, God damns Crafty, throwing him into the real world, where he will live and suffer while God makes peace in the cartoon world. And so Crafty is killed and resurrected again and again, knowing that his suffering is saving the world and vowing to some day return to the cartoon world “and on that day overthrow the tyrant God and build a better world.” [continued]

April 5, 2021 @ 7:54 pm

Was Crafty’s world the best art Chaz Truog did for Animal Man? Is it possible he was just totally mismatched for superheroes whilst still having skill at other elements? Or am I just misremembering the issue?

April 8, 2021 @ 5:40 pm

I posted a long comment about Truog on the installment before this. TLDR, I think he’s an underrated artist who actually did some good-to-excellent work on this series — mullet haircuts notwithstanding.

But yeah, this particular issue is a high point. And not just Crafty’s world! Look at the resurrection sequence, and the final splash panel with the wild-eyed Crafty and the wheeling vultures. Then look at the panel above, with his subsequent resurrection several pages later. The parallelism is very well done. There’s a bunch of stuff like that in this issue.

Doug M.

April 12, 2021 @ 5:56 am

Oh Ell! that is both an amazing parallel between Urizen and the coyote, and the transition between the paragraphs when it happened! Love it.

I think I rather like Truog’s artwork too, I can see how it really sings in the panels above and in Crafty’s world. I love the phrase in panel 1202 that describes how the dead eyes looked like how they were “glazed like pots”.