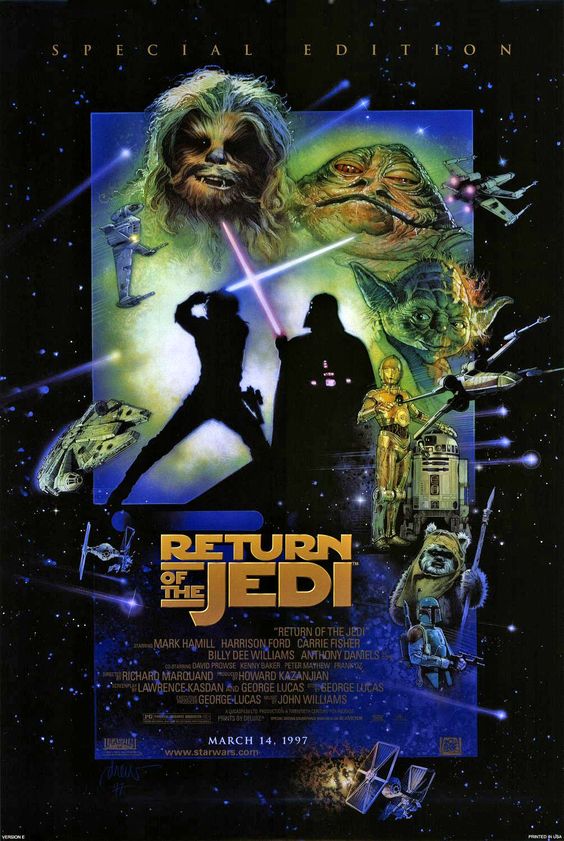

An Increasingly Inaccurately Named Trilogy: Episode VI – Return of the Jedi

The standard line about the original trilogy is that Return of the Jedi is its weak link. It will surprise nobody to learn that I’m suspicious of this logic, which is at its heart rooted in an aesthetic that says that big reveals like Vader being Luke’s father are good and Ewoks are bad, but it’s nevertheless worth recognizing that Return of the Jedi is the one film in the original trilogy that’s markedly improved by the presence of the prequels. This isn’t a new observation – it’s at the heart of the famous Machete Order, which suggests putting the prequels between The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi, and which basically prompted this entire series with its argument for why you should skip The Phantom Menace while doing this, which was the immediate cause of my remarking that prequel criticism was generally worse than the prequels themselves.

The standard line about the original trilogy is that Return of the Jedi is its weak link. It will surprise nobody to learn that I’m suspicious of this logic, which is at its heart rooted in an aesthetic that says that big reveals like Vader being Luke’s father are good and Ewoks are bad, but it’s nevertheless worth recognizing that Return of the Jedi is the one film in the original trilogy that’s markedly improved by the presence of the prequels. This isn’t a new observation – it’s at the heart of the famous Machete Order, which suggests putting the prequels between The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi, and which basically prompted this entire series with its argument for why you should skip The Phantom Menace while doing this, which was the immediate cause of my remarking that prequel criticism was generally worse than the prequels themselves.

The problem that Return of the Jedi has on its own merits is Luke’s constant assertion that there’s still good in Darth Vader, a claim that not only lacks justification in the films but is actively unjustified by the sheer degree that Darth Vader is an ostentatious force of pure evil badassery. As we’ve discussed at length, it’s not that the claim that there’s some good in him is particularly justified by the prequels either, but at least the line is uttered by Padme in Revenge of the Sith, and more to the point, the prequels put significant effort into making Anakin an actual character. It’s difficult to actually imagine the Darth Vader of A New Hope and The Empire Strikes Back making an abrupt face turn, but while it’s still a bit out of left field, it’s perfectly possible to imagine the Anakin Skywalker of Attack of the Clones and Revenge of the SIth doing it. (I mean, hell, he’s so fickle in Revenge of the Sith that it’s basically possible to imagine him doing anything.)

More broadly, the relationship between Luke and Vader is, in the original trilogy, a pure abstraction – it matters entirely because of the basic ideological valences of fathers and sons. Indeed, the fact that it literally only matters because of patriarchy goes a long way towards explaining the weirdly outre status of Leia within this relationship, with her involvement a somewhat disposable third movie reveal in which she gets played as the fool, getting a piece of information the audience already knows and that has no actual bearing on the plot. But as a conclusion to the entire Lucas-governed saga it’s a far deeper relationship, and that gives the film new weight, a fact reflected in Lucas’s decision to replace Sebastian Shaw with Hayden Christensen in the final scene. (Honestly not a bad decision, though he probably should have replaced Alec Guinness with Ewan MacGregor in this and The Empire Strikes Back to set it up better.)

But it’s worth interrogating why this should be the case. After all, it’s not obvious that the solution to an undercooked finale is to go back and add more stuff before it while not actually changing anything about the finale itself save for swapping out “Lapti Nek” for “Jedi Rocks.” Indeed, in most circumstances adding more things that a finale is expected to resolve is the exact opposite of fixing the problem. Part of the issue is what we’ve already discussed – the concerns set up by A New Hope and The Empire Strikes Back are abstractions based on archetypal relations. But this isn’t a fault – indeed, it’s baked into George Lucas’s basic idea of a Buck Rogers-style serial.

No, the important thing is that Return of the Jedi marks the point in Lucas’s chronological development of Star Wars where the movies start getting a bit weird. I mean, The Empire Strikes Back isn’t without its utter barminess, featuring as it does both the Exogorth and Yoda. Even A New Hope has the Cantina scene. But both films spend most of their time on fairly standard space action serial ideas. By the time of Return of the Jedi, however, Lucas was running out of obvious ideas, and so was forced towards things like, well, Jabba the Hutt’s palace and the Ewoks. This trend only continued over the course of the prequels, and so it’s not a surprise that adding them to the narrative helps Return of the Jedi, in that it becomes a film that balances the approach of the five previous instead of a weird aberration.

Obviously the consensus is not that Lucas running out of obvious ideas was a good thing. As I said, I’m naturally inclined to be skeptical of this. Doctor Who fandom has a famous factionalization into “guns” and “frocks,” with guns preferring action and exploding Daleks and the like, while frocks like stories that are much more like, well the prequel trilogy. And I’ve got a long critical track record of standing up for frocks. All the same, it’s clearly the case that the prequels simply are not as good movies as the original trilogy, which isn’t exactly a ringing endorsement of Lucas’s weirder instincts.

The problem, though, isn’t Lucas’s weirder instincts so much as the fact that his weirder instincts lead him away from his strengths. By and large, as sheer weirdness increases, clarity of storytelling has to as well. Lucas, meanwhile, is deeply undisciplined in his storytelling. His plots are sloppy and ill-structured, his characters are bland archetypes, and his dialogue is cornball. And as his more (literally) alienating ideas come to the forefront these failings get less and less room to hide.

The irony of this, though, is that even though his weirder instincts drag him away from his best filmmaking, they’re still on their own merits his absolute best tendencies. Even A New Hope works largely because of Lucas’s propensity for slight strangeness, with much of its texture defined by touches like the Jawas, Chewbacca, or throwaway phrases like “moisture farm” and “clone wars.” The decision to have the initial viewpoint characters be C-3PO and R2-D2 is astonishing in its out-of-left-fieldness, and yet it’s one of the most important in the film, a bold setting of expectations that notably convolutes attempts to pretend the film begins with Luke’s call to adventure and not Leia’s droids. And for all that the original trilogy is better, its overall plot of generic rebels overthrowing generic fascists is far less interesting than the collapse of a corrupt democracy. Indeed, if you want to boil the core argument of An Increasingly Inaccurately Named Trilogy into a single sentence, it’s basically “the movies the prequels are failing to be are much more interesting than the ones the original trilogy are succeeding at being.”

But then there’s Return of the Jedi. A film where Lucas’s weird instincts have the moderating force they so desperately need in the form of Lawrence Kasdan, who dutifully makes sure the film remembers to actually be about something most of the time. Sure, Lucas’s weird instincts also just aren’t on full blast yet (notably he blatantly can’t think of anything other than “the Death Star again maybe?”). But there’s also a clear arc with narrative purpose to the strange sequences. The Jabba the Hutt opening is even more cut off from the rest of the film than Hoth is in The Empire Strikes Back, with the film all but restarting with Mon Mothma’s appearance. But it still has a clear arc of demonstrating how much the events of the previous film have changed Luke and a nifty gimmick of sequentially reintroducing the characters as the rescue scheme unfolds. As a result the weird bits are delightful instead of simply alienating, and the sequence is a classic.

But even better are the Ewoks. Jabba, after all, is grotesque, but his sequence is decidedly not frock, and Carrie Fisher’s got the metal bikini to prove it. The Ewoks, on the other hand, are an absolutely bonkers turn that clashes gloriously with the operatic grandeur of the three-way showdown on the Death Star. And yet they’re handled with just as much attentiveness as the Jabba the Hutt sequence. Everyone involved is clearly committed to making the Ewoks work as a concept, and is hell-bent on taking them seriously. The Ewok death scene is very possibly the most brilliant thing in the entire saga, a rare moment in which the story decides to just go for it and really push an idea as far as it can go. Sure, the battle for Endor hasn’t got the visceral thrill of Hoth or the trench run, but it’s an utterly gonzo notion played with skill and conviction, and I think that’s a fundamentally better thing to be.

Like most of Return of the Jedi, though, the Ewoks really shine in the context of the whole saga, where they more clearly provide a sense of thematic resolution. As mentioned, taken on its own the politics of the original trilogy are not particularly complex. And this poses something of a problem for the saga as a whole; Revenge of the Sith ends with a complex network of moral and political concerns that it inadequately resolves before ostentatiously punting them onto the next generation. The original trilogy, however, does not pick any of them up. One can divine interesting answers, and the saga’s not over yet, but it’s simply not the case that A New Hope or The Empire Strikes Back are particularly interested in the questions asked by Revenge of the Sith.

But the Ewoks do. They’re another iteration of the prequel trilogy’s most fascinating thematic concern, namely the practice of considering groups as subhuman, whether the droids, the Tusken Raiders, the clones, or the practice of slavery. The Ewoks are filling the classic pulp adventure role of “the savages,” but avoid the crass racial stereotypes that characterize a lot of the prequel trilogy’s alien species. Indeed, they’re one of a handful of successful ways to incorporate the trope of savages into adventure fiction that don’t involve ugly racial implications.

More than that, however, the Ewoks finally provide something of a resolution to the longstanding issue. They form an entirely functional rebellion of their own, not only rising up against their oppressors but clawing out a place within the human-dominated social order. It’s easy to make too much of this; the Ewoks are, like R2-D2 and Chewbacca, left untranslated, which makes it difficult to ascribe much depth to anything they do. But the fact that the Empire’s climactic downfall is fundamentally down to a subaltern indigenous population rising up against oppression is valuable – a significant statement that makes editing Naboo into the closing montage sensible in spite of the fact that we’ve not spent any significant time there since Attack of the Clones, just because the Gungans are one of the most obvious parallels to the Ewoks (though not quite as blatant as the Jawas). This is in many ways a more meaningful sort of closure than anything character-based could possibly be – one rooted in what the saga has been about instead of in its raw iconography.

And so the saga as Lucas envisioned it comes to a close. It is worth noting, this would have been enough. Either as a trilogy or a sextet, Return of the Jedi would have made a fine conclusion to Star Wars, a series that was always grounded more in George Lucas’s desire to see his daydreams realized on a movie screen than in anything else. Star Wars has always been more than just these six movies, yes, but as a statement of artistic vision in science fiction they are peerless. Even as they acquired countless imitators, Lucas remained singular, strange, and at times downright baffling. On some level quality seems no more interesting a question to raise about Lucas’s work than it is about Henry Darger’s. The only difference is that somehow Lucas’s mad visions got made into multimillion dollar movies instead of drawings abandoned in a Chicago apartment.

But, of course, the consequence of that is that his vision was never going to remain his own. There was always too much money in allowing it to be otherwise. This is not some suggestion that Lucas’s vision was somehow compromised by his tendency to keep one eye on the toy market. There is no “Lucas’s vision” separate from the commercial concerns, a fact that does not detract from its delightful weirdness in the slightest. Rather, it is an acknowledgment that this vision could never endure as the untouched center of Star Wars. It was always going to become a franchise, not a saga. This has its merits – Jack’s done a stellar job of illustrating how interesting Rogue One is over the last few weeks, and I’m going to have plenty of nice things to say about The Force Awakens next week. But there’s still something that even I, who, twelve thousand words into this thing still don’t actually like Star Wars very much, find poignant about seeing Lucas’s vision pass into history within it.

Ranking

- Return of the Jedi

- A New Hope

- Attack of the Clones

- The Empire Strikes Back

- The Phantom Menace

- Revenge of the Sith

March 6, 2017 @ 4:05 pm

Jedi has always been my favorite of the original trilogy.

I do think the post-colonial reading ends up being more complex than you present, with the Ewoks actually being even more empowered in that they themselves don’t actually appear to have been colonized yet. The Imperials don’t construct their bunker with Ewok slave labor, have an Ewok “Friday” on-site; they don’t have a stockade full of “vermin Ewoks” or keep them as pets; they haven’t even displaced the Ewok village. Either they haven’t yet gotten around to doing so, or they just don’t care enough about the Ewoks yet to do anything.

Within that context, we’d expect more of a cargo-cult response. But the actual Ewok motivation turns out to be remarkably principled and deeply associated with themes of slavery running through the movies. It is a droid, after all, who the Ewoks identify as the superior being when they find our heroes. C3P0’s comment that impersonating a god is against his programming demonstrates the extent to which his subsequent actions empower him; further, his attempts to free the others only bear fruit when he demonstrates (through Luke) that he has Force powers, while the lack of a connection between droids and the Force has been an undercurrent justifying their continued servitude and status as property.

And once freed, our heroes gather Ewok support, but not because the Ewoks have a long list of grievances against the Empire based upon their past enslavement. Instead, they incorporate Han, Luke, Leia and Chewbacca into their tribe (meaning that Luke’s victory is now the Ewoks’ victory), and they turn against the Empire on the basis of the story C3P0 tells: in effect, they oppose imperialism not because of what it has done to them, but what it does to others.

Then the “primitive savages” who can’t match Imperial technology manage to win their battle. The subset of fans disgusted by this sequence for its unrealistic qualities (“Logs beat an AT-ST?” Cue recital of armor thickness and tensile strength or claims that Wookies would have been better) have missed that the whole battle is a metaphor for a larger struggle against imperialism. The Rebels include both former Imperials and their slaves/victims; the Ewoks express such strength because they are neither, yet, instead being outside the system, the “soon-to-be-oppressed.” No wonder the movie refuses to translate their speech or to subtitle it. These are not Tonto-figures speaking pidgeon English as “noble savages,” but an independent polity worthy of respect and acting out of principle to destroy the Empire. Given the chance at cargo-cultism, they opt to worship droid technology, specifically, and thus align themselves with the enslaved over the slavers, the servants over the masters. No wonder a specific subgroup of the fandom despises them.

March 7, 2017 @ 5:14 am

Funnily enough, I believe the MythBusters (at least two of whom actually worked on Star Wars as VFX designers) demonstrated the Log vs. AT-ST scene was realistic: Those logs have a lot of mass, and get them going fast enough and you’d be surprised at what they can do. Royally fucked up a 4X4.

March 7, 2017 @ 7:03 am

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R2Nnrco01Bo

Start watching at around 40:00 or so…. Logs vs Armored Car..

March 6, 2017 @ 5:47 pm

Rome never looks where she treads.

Always her heavy hooves fall

On our stomachs, our hearts or our heads;

And Rome never heeds when we bawl.

Her sentries pass on—that is all,

And we gather behind them in hordes,

And plot to reconquer the Wall,

With only our tongues for our swords.

We are the Little Folk—we!

Too little to love or to hate.

Leave us alone and you’ll see

How we can drag down the State!

We are the worm in the wood!

We are the rot at the root!

We are the taint in the blood!

We are the thorn in the foot!

Mistletoe killing an oak—

Rats gnawing cables in two—

Moths making holes in a cloak—

How they must love what they do!

Yes—and we Little Folk too,

We are busy as they—

Working our works out of view—

Watch, and you’ll see it some day!

No indeed! We are not strong,

But we know Peoples that are.

Yes, and we’ll guide them along

To smash and destroy you in War!

We shall be slaves just the same?

Yes, we have always been slaves,

But you—you will die of the shame,

And then we shall dance on your graves!

March 11, 2017 @ 10:23 am

A fantastic poem, but a very strange one for an arch Imperialist to write.

March 19, 2017 @ 5:03 am

Kipling was complicated. He wrote “The White Man’s Burden,” a clear paean to western/white supremacy. He wrote “The Ballad of East and West,” celebrating mutual respect between westerners and nonwesterners as equals. And he wrote “Letting in the Jungle,” celebrating the triumph of jungle over civilisation. One can find similar complications in Edgar Rice Burroughs and Robert E. Howard.

Speaking of Howard, I suspect Kipling’s poem influenced Howard’s fascinatingly strange obsession with the Picts:

https://aaeblog.com/2008/08/08/he-picked-picts-to-depict/

March 6, 2017 @ 7:29 pm

Return was far and away my favorite as a kid, but to be honest the more I watch it now the less and less I like it (though I have to say the Ewoks have always been one of the highlights for me, and the backlash against them is ridiculous. It says a lot about SW fandom that the two most overtly “kiddie” films (this and TPM) are by leagues the most hated in the franchise).

My big problem with Return has always been the awful things it does to Leia–the slave bikini is obviously as bad as everyone says, but more damaging to me is the sister retcon, where Leia becomes quietly devalued as an individual character and starts to exist only as a counterpart to the men–instead of being “Leia”, she’s now effectively “Luke’s Sister” and “Han’s Girlfriend” (even Force Awakens, with all the strides it makes towards better female characters, can’t help but put her in those same functions).

The whole film just doesn’t allow her to really exist in of herself anymore–what little she gets in the Boushh costume is devalued by her almost immediate damseling (which is so ridiculous–there’s absolutely no reason for Luke’s plan to be this convoluted, and the film seems to tie itself up just to get her in the slave outfit), and once we actually get to the rebellion it’s Han and not her that gets to actually lead the squadron. The film as a whole seems to only want to put her in stereotypical ‘feminine’ roles–the damsel, the maternal figure, the supportive counterpart to the Brooding Man Hero. It’s probably the most embarrassing film in terms of what it does to its female characters, which is saying quite a bit for the Star Wars franchise.

Other than that I just dislike how simplified the film becomes–the more complex morality introduced in Empire gets squared away here in favor of an over-the-top Big Bad, retconning Vader’s choices as being the result of an Evil Corrupting Influence, and the whole thing just feels like a dumbed-down version of the original film. Add on top of that the bad structuring (the Jabba sequence is overindulgent to the extreme–there’s no way the plot function there demanded two entire setpieces) and the rather limp direction and SFX work (outside of the astounding puppetry it’s the cheapest looking of the original films), and yeah, this one just hasn’t held up for me.

March 7, 2017 @ 5:16 am

I’ve never been a Star Wars fan so I don’t even know why I’m commenting, but it’s the treatment of Leia that always killed this movie for me too, for much of the reasons outlined here.

Big ups Ewoks.

March 6, 2017 @ 8:49 pm

The Leia reveal really is down to Lucas just wanting to avoid having to deal with resolving a love triangle (although the whole implied celibacy of becoming a Jedi could have dealt with it quite adequately).

A more interesting resolution that could have been developed out of the revelation would have been for both Luke & Leia to confront The Emperor & Vader at the climax.

March 6, 2017 @ 9:31 pm

Personally, I find it hard to rate Return at all. It’s got the best fifteen minutes or so of the entire series in it, but it’s also got the worst other ninety minutes.

The opening bit at Jabba’s Palace never worked for me. I can see the arguments for it, and the notion that the whole (six-part) Trilogy is really just a sequence of these half-hour serial episodes, where three or four have been edited together to make a single movie is really quite an interesting one. (And it shows why Star Wars itself is a rogue element that needs to be discarded or drastically restructured in order to properly fit this newer model.)

I quite like the middle bit on Endor. There’s still very little that matches the speeder bike chase for sheer visceral excitement (but then again, I like the Light Cycles sequence in Tron too.) And the whole implication that the Ewoks are going to eat their prisoners is nicely underplayed.

But then you get to the grand finalé where Lucas gets too self-indulgent by making the final battle split three ways so that he can cut between them to make it feel as though there is more tension than there actually is.

And yet, despite the fact that the confrontation with the Emperor definitely severely diminishes Vader’s role, that sequence is so good as a payoff to one of the best bits of retconning ever, that it still works for me. The rest of the battle is just filler though. Sure, there’s some barbed political commentary going on, but it never really felt real to me (I wonder if that’s because I found the politics in the prequels much more interesting and subtle?)

I’m glad that Phil’s final list goes so flagrantly against the general consensus, although that was clearly his intent from the start, and I think he mostly gets away with it. 🙂

March 6, 2017 @ 11:39 pm

I remember an interview with Lucas in Rolling Stone-and bear in mind, Lucas has always been a bit of a mythologist about his long term story telling plans, so how he told a story in 1983 wasn’t really how he told it later-that the choice to make Leia Luke’s sister was decided in the writing of Return, where they needed a reason for Luke to become angry enough to fight Vader and “Vader threatens to turn Leia!” was what they decided on.

Which sure sounds like Lucas and his cavalier way of writing movies. And in a lot of ways makes what happens to Leia in this movie worse, since if it wasn’t just Lucas pulling stuff out his ass in an interview, it means that she was made Luke’s sister really late in the game, in an utterly half-assed fashion. And the character has suffered ever since, since even the EU versions only made grudging motions towards being a Jedi and was defined, as Phil said, to the end as “Luke’s sister” and “Han’s girl.”

March 8, 2017 @ 11:44 pm

If true, it makes me wonder what Yoda’s line in Empire “There is another” was about. I always thought it foreshadowed Leia as Luke’s sister, but now I’m thinking maybe it’s referring to Vader.

March 9, 2017 @ 5:13 pm

That line was meant to give the idea that we could lose Luke and not end the story, so people might think he’d actually die. The idea became to introduce his sister as a new character, perhaps in a second trilogy. And then they hurriedly resolved both aims with “Leia is his sister.”

March 7, 2017 @ 12:18 am

Another beautiful ‘frock’ moment is the crying owner of the Rancor. Always stuck in my head along with the Ewok death as one of the purest moments of pathos in the saga.

March 7, 2017 @ 2:43 am

The Rancor trainer/handler’s moment of utter despair at the loss of his beloved pet/monster is ‘the moment’ of the entire original trilogy for me. It’s one of the rare moments, (even though played for laughs) of verisimilitude that made me believe in the universe around the main characters.

March 8, 2017 @ 3:25 am

To me, Star Wars is always at its best when it’s humanizing the alien (“alien” in this case including humanoids with alien cultures or behaviors). That scene is probably one of the best, but I always felt the cantina scene worked well not just because of the sudden flood of weird aliens in it, but that they’re all just lounging around, getting out of the heat, enjoying a drink, betting and dancing and having a good time. They’re aliens, sure, some of them are straight up monsters, but they’re still people.

March 7, 2017 @ 2:56 am

I always loved that moment. Sure, it was a giant murder machine, but it was HIS giant murder machine.

March 9, 2017 @ 6:35 pm

I found it easier to empathise with the grief of the keeper of the Rancor on the creature’s death – it was after all an animal kept captive for the enjoyment of a psychopath – than to empathise with Luke on Vader’s death.

Vader, let’s face it, was a genocidal fascist who tortured most of the leading characters during the orginal trilogy. Going gooey over his sprog at the end didn’t really redeem him.

Perhaps worse, Vader was someone who got promoted, despite making a complete hash of everything he tried, just because he was in the same minority cult as the big boss. People like that I really hate.

March 13, 2017 @ 10:15 pm

I’m reminded of this webcomic:

http://whosthewhatnow.tumblr.com/post/34666694626/dear-disneypixar-ive-got-an-idea-for-you-to