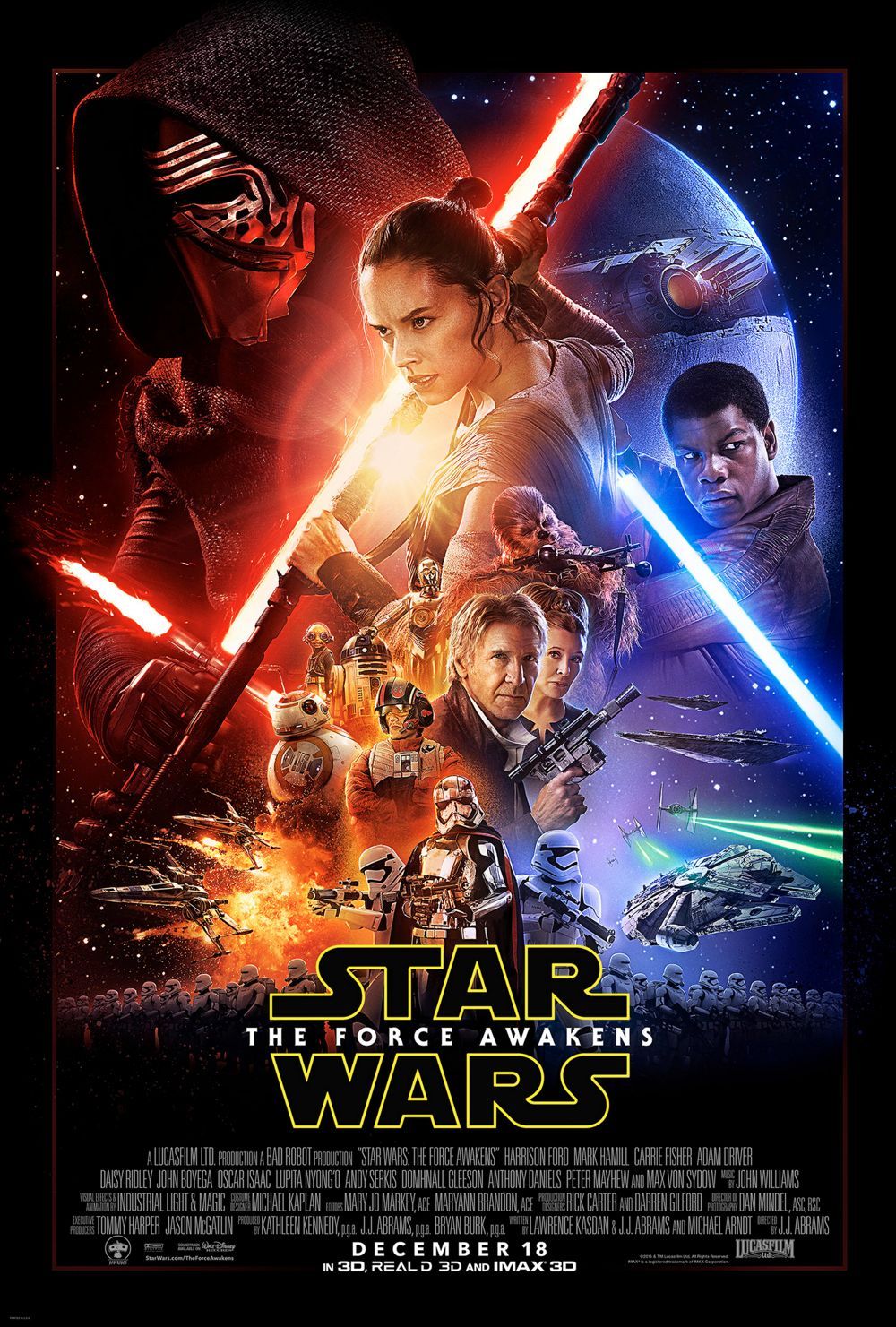

An Increasingly Inaccurately Named Trilogy: Episode VII – The Force Awakens

It is damning with faint praise to say that “George Lucas done right” is a task perfectly suited to J.J. Abrams’s abilities, which is of course why it’s such a fun thing to assert. It’s not quite true, for reasons we’ll get to, but there’s more truth to it than not, and for the most part the truth is more revealing. Certainly it’s very obviously the logic Disney applied in hiring Abrams for the job of making Star Wars into a viable property again, and their benign cynicism is on the whole easy to understand. The prequels had made Return of the Jedi a better end to the saga in more ways than one, their famous awfulness drying up the bulk of the cultural goodwill the franchise had while muddying the question of what Star Wars should look like post-1983 with a host of unsatisfying answers that nevertheless needed to be considered.

It is damning with faint praise to say that “George Lucas done right” is a task perfectly suited to J.J. Abrams’s abilities, which is of course why it’s such a fun thing to assert. It’s not quite true, for reasons we’ll get to, but there’s more truth to it than not, and for the most part the truth is more revealing. Certainly it’s very obviously the logic Disney applied in hiring Abrams for the job of making Star Wars into a viable property again, and their benign cynicism is on the whole easy to understand. The prequels had made Return of the Jedi a better end to the saga in more ways than one, their famous awfulness drying up the bulk of the cultural goodwill the franchise had while muddying the question of what Star Wars should look like post-1983 with a host of unsatisfying answers that nevertheless needed to be considered.

Abrams, in this context, was an eminently safe pair of hands. He’d already rebooted Star Trek with an aesthetic that could uncharitably be summarized as “wishing it was Star Wars,” and with Super 8 had shown himself a skilled practitioner of 1970s nostalgia. More broadly, he was a director who could solve both of Disney’s immediate problems. On the one hand, he was fluent and respected enough in geek culture to keep rabid Star Wars fans on board. Such fans make up a negligible share of the audience for a major tentpole film, but are vocal and engaged enough that losing them creates a significant marketing problem. On the other hand, he was actually capable of making films that people liked and wanted to see.

I noted when I reviewed the film that Abrams was decidedly more interested in making a good Star Wars film than he was in making a good film. This is indisputably true. The Force Awakens works because it is a well-executed Star Wars film. Abrams strikes an intelligent balance between the obligatory wipes and stylistic tics that define the saga and more dynamic, lively moments. Much of this is little stuff – the shuddering, darkly lit shots of Storm Troopers in their shuttles, for instance, or the cut from Finn’s helmet to Rey in her goggles – that hardly merits praise, but there’s still a form of sophistication to it that Lucas simply wasn’t invested in. And these are mixed, in the early sequences, with teasing shots of ruined Star Wars iconography: a crashed Star Destroyer, or a fallen AT-AT. There’s a cheeky, illicit thrill – a child getting to play with the grown-up toys, and yet rising to the occasion so that their exuberance is tempered with real technical nous. Abrams is awed by the material, but not overawed.

This is, in the end, because Abrams is a joyless cynic interested only in appearances and iconography. Abrams is, throughout the film, singularly interested in making sure everything looks good. Over and over again the tone the film reaches for is “here’s a classic Star Wars moment… but it looks good, no?” And Abrams’s sense of classic Star Wars moments is thoroughly predictable, drawing almost entirely from the original trilogy while ignoring the prequels. What this means is that the film is as devoid of Lucas’s gonzo instincts as it’s possible to be while still being the seventh Star Wars film. The only place things flirt with overt weirdness is the sequence on Takodana, and its weirdness is all borrowed imitation of the cantina scene. Past that, the film is determined to reassure its audience that there’s not going to be anything like Jar-Jar Binks or the Ewoks here.

What Abrams brings, on the other hand, is basically a Kasdan-like competence applied throughout the production. (And of course, Kasdan’s around on script duty.) Abrams spent enough time in the killing fields of dramedy television to be good at mixing action and comedy, and the bits that are supposed to be funny have an easy charm that Lucas’s work doesn’t. Even broad physical comedy like the BB-8 lighter gag plays out with effortless-feeling comic timing as opposed to broad silliness. Characters have clear motivations and arcs across the film. There’s never a moment where the film does not seem to know what it’s doing. All of this is straightforwardly good, just as it was when Kasdan arrived to apply some discipline to Lucas’s vision.

But what’s really important about Abrams is that he extends this clarity to the thematic elements. The high point of this is undoubtedly Kylo Ren, who is a wickedly clever synthesis of Lucas’s varying conceptions of Anakin Skywalker/Darth Vader. Jack has already wisely noted that Abrams offers a very politically right-on update to Star Wars, but the decision to forgeround Anakin’s MRA tendencies in crafting a new generation of the archetype is by some margin the choice of his with the most teeth. Abrams wisely sequences the revelations about him for maximum effect. He’s introduced first as a sadistic quasi-Vader, thus relieving Adam Driver of the difficult challenge posed to Hayden Christensen whereby one must play an angst-ridden teenager first and then convincingly make him a dark lord of evil. And all of this, in turn, is established before the mythos-based reason why the audience should give a fuck about him, namely that he’s Han and Leia’s son.

This is also, sensibly, Abrams’s strategy for introducing a new set of protagonists. In contrast to how A New Hope is forced to function, the film does not open with familiar characters from the previous trilogy, but rather with a tangible absence of Luke, a decision that’s sustained through the entire film. Han and Leia are similarly withheld, which gives Rey and Finn time to breathe instead of having to compete with the mythos right off the bat. Abrams also eschews Lucas’s tendency towards treating protagonists as things to observe, making a film that’s actually structured around Rey’s Hero’s Journey that’s long on scenes where the viewer is invited to empathize with her. This is undoubtedly wise, not because that approach is inherently better than Lucas’s more Brechtian tendencies, but because it’s necessary to sell the idea of a Star Wars film with no obvious Skywalkers. Rey has to win over a mildly skeptical (and sexist) audience, and the more intimate approach to her story accomplishes that.

The other thing that holding back the familiar characters for a bit accomplishes is the inspired decision to give Han Solo the structural role occupied by Obi-Wan in A New Hope. This works not only because Harrison Ford is straightforwardly the best actor of the previous generation, but because it creates a satisfying parallelism – Obi-Wan and Han were both the most morally interesting characters of their respective trilogies. By having him be the relic of the past that serves as a launching pad for the next generation of protagonists (and we should note that this is also the Qui-Gon role) Abrams sets his film up as a moral progression of the series that takes it forward towards new questions and perspectives.

In this regard we should note the obvious early frontrunner for this role in Episode X: Finn. There is an unexpected horror in his character – a fascist army obtaining its shock troops by stealing children is uncomfortable in its closeness to how the world actually works. Like Anakin’s enslavement (and quite unlike “they’re clones with suppressed intelligence”), there are aspects of this concept that are simply too upsetting to depict within the framework of what Star Wars is. Obviously he’s another iteration of the familiar trope of subaltern and objectified people – the whole “literally doesn’t have a name” thing kind of settles that. But he’s the first such character since Anakin to obtain any sort of protagonist status, and the first ever to do so as a straightforwardly sympathetic protagonist. Even if the subsequent two parts of this trilogy don’t do anything interesting with this (just as The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi don’t really find much to do with Han’s moral implications), there’s a weighty moral progression in the very fact of it.

This is echoed in the larger transformation of the mythos as the role of the defeated Empire is taken up by the First Order, who are a new iteration of the familiar space fascists. This time, instead of being an evil within or an established government, they are a defined military enemy within the galaxy. This creates a pattern that had not previously been part of what “starting a new trilogy” meant within Star Wars, in that the fascists in both A New Hope and The Force Awakens take on the basic form of the previous trilogy’s good guys. The First Order is, by all appearances, a rebellion.

The good guys, meanwhile, have turned into a Resistance. This is a subtle upgrade, but one emphasized elsewhere in the film, most obviously in Maz Kanata’s speech about evil and the taking many forms. The saga has always acknowledged the dark side as an eternal threat, but here it’s more a cyclic one – something that’s defeated and then comes back in a new form, against which one must be perpetually vigilant. “Resistance” nicely captures this, acknowledging that this opposition must be a part of everyday existence. There was no resistance to speak of in the prequel trilogy, and this is certainly part and parcel of how the Empire came to rise. Note also the “temptation to the light side” idea, which further enriches the notion of this as a perpetual struggle instead of, as the prequel trilogy suggested, a series of wily plots from a secretive two-man crew of Darths.

Obviously there is much that is in the air here. Firm comment on how this new batch of thematic pieces fit together and, more to the point, how they don’t will require two further movies. How Rey fits into the generational Skywalker saga, where Finn fits into the overall design, the precise contours of what the First Order is, and for that matter how they handle the obvious importance that Princess Leia has to the narrative as the person saying that there’s still good in the bad guy given Carrie Fisher’s death (I say recast the role; if Alec Guinness can be replaced, anyone can be.) are all questions whose answers will open and foreclose possibilities. But Abrams, in his meticulousness, has also left a narrower field of possibilities than either The Phantom Menace or A New Hope did. The Force Awakens is straightforward even for a Star Wars film. This is not a criticism, to be sure – much of the twistiness of previous Star Wars films has been due to poor filmmaking, not well-done ambiguity. But it’s an interesting situation going forward.

The other interesting thing going forward, of course, is the lack of actual architect for this trilogy. Abrams remains an executive producer going forward, and surely handed some information over to Rian Johnson, but is far more out of the picture going forward than Lucas was on The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi. Rian Johnson, on the other hand, is a shockingly bold choice for The Last Jedi – the first time the series has ever been graced by a writer or director who’s already done better stuff than Star Wars. Indeed, I’m half tempted to do a quick triptych of posts on his filmography before December, just to really set ridiculous expectations for myself in covering The Last Jedi.

But for now we bring this trilogy to a temporary close. What shall I say? I still don’t particularly like Star Wars, in the sense of not feeling any investment in its mythology. It contrasts sharply with Doctor Who in this regard, and even with the Marvel Universe. It pales even behind Game of Thrones, which is a show I hate to love. But I am, at least, invested in the question of what’s next and looking forward to The Last Jedi. Yes, this is in part because of Johnson, a director I’ve followed avidly since before The Brothers Bloom. But that doesn’t diminish the role of The Force Awakens in that. As beginnings go, it’s the most promising that Star Wars has ever had.

Rankings

- Return of the Jedi

- The Force Awakens

- A New Hope

- Attack of the Clones

- The Empire Strikes Back

- The Phantom Menace

- Revenge of the Sith

March 13, 2017 @ 1:20 pm

You touch on what is for me, perhaps, the most interesting aspect of TFA; and that is Finn, especially the likelihood of there being more like him in the massed ranks of stormtroopers regularly mowed down as canon fodder in the original trilogy, in TFA, and currently on TV in Star Wars Rebels series.

My seven-year-old son commented while watching some random stormtroopers swapping quips just before being taken out by our series regular heroes in a recent episode that ,”They sounded like Finn.” And the concept of some of the stormtroopers being ‘good’, or at the very least likeable struck him silent for a while.

Hours later he came to me to bring up an incident in an old episode of Clone Wars (we just completed a full six season binge about three weeks ago). Three Battle Droids were facing down a rampaging Jedi, intent on cutting his way past them. Droid #1 tries to rally his troops with a, “Stand firm, there’s three of us and only one of him.” The droids swap comic double takes, and he drops his blaster to his side and comments, “What does it matter!” And all three are unceremoniously dispatched by said Jedi, and forgotten. All played for comedy. And we did laugh when we watched it.

The Finn/stormtrooper quandary had made him rethink this incident, and maybe start to ponder some of his young certainties about how the world worked.

“What if droids had feelings and friends, too?” he asked innocently.

March 19, 2017 @ 5:16 am

“he’s the first such character since Anakin to obtain any sort of protagonist status, and the first ever to do so as a straightforwardly sympathetic protagonist”

This is true only if one ignores the tv shows (especially Clone Wars, which goes as far as it can toward exploring the oppressed status of clones and droids without actually declaring the Jedi to be awful people).

March 13, 2017 @ 1:26 pm

I didn’t think the phrase “Lucas’s more Brechtian tendencies” would ever be a phrase I nodded in agreement with, but here we are.

March 13, 2017 @ 1:46 pm

I’m half tempted to do a quick triptych of posts on his filmography before December, just to really set ridiculous expectations for myself in covering The Last Jedi.

Do it. Do it do it dooooo iiiiit.

March 13, 2017 @ 2:45 pm

If anything, to finally convince me to watch The Brothers Bloom despite my brother’s negative reception towards the film.

March 14, 2017 @ 1:40 am

Your brother is hella wrong.

March 14, 2017 @ 1:47 am

If that was the only thing he was wrong about, I’d be much happier. Shame he also has to be an Amazing Atheist fan boy.

March 14, 2017 @ 1:34 am

Brick is brilliant, Looper is fun, and Brothers Bloom is about the power of telling stories. Do it.

March 14, 2017 @ 1:41 am

March 13, 2017 @ 5:49 pm

Wow, the structural connection between Qui-Gon, Obi-Wan, and Han is something I’d never considered before. But you’re right, each trilogy begins with a member of a generation that’s on its way out helping kick things off and then passing the torch along and getting killed by a Sith Lord’s lightsaber.

March 13, 2017 @ 10:21 pm

I like to imagine that the development meeting that came up with Kylo Ren went something like this:

– We want a villain that will be as iconic as Darth Vader.

– But we’re never going to come up with a villain as iconic as Darth Vader.

– Let’s make that our villain’s concept then: he wants to be as iconic as Darth Vader and knows he’s never going to be.

And the rest of the film follows that (for example it’s blatant following of the original structure and iconography): it’s a spectacle sf movie that is openly about being a spectacle sf movie after Star Wars; which is something that only the Star Wars franchise can really do.

March 14, 2017 @ 6:12 pm

That’s certainly how I see Kylo’s genesis. It’s the Infinite Improbability strategy; put the narrative problem itself in the text in such a way that it becomes its own solution.

March 14, 2017 @ 11:10 pm

I remember when TFA first came out, one of the bits of news I came across involved how there were a ton of Kylo Ren toys manufactured, but which no one could move. And parents and children at stores and online were asking for more Rey merchandise that corporate never thought to make. Ren was featured really prominently in the trailer too.

Basically, because Kylo Ren was the big villain with the coolest sword and the badass mask, the marketing and merchandising bros must have thought he’d be the best merchandising hook for the movie. They probably also bought into the notion that only boys would buy Star Wars toys. I don’t think the folks in charge of the initial marketing push for the film (if they even bothered to watch the film, which I doubt) had any idea that A) girls like sci-fi or B) Kylo Ren is, from top to bottom, designed as a pathetic wretch whose pale imitation of his grandfather invites only contempt.

March 15, 2017 @ 5:22 am

Right after the movie came out, I was talking with some fellow Star Wars fans and Kylo Ren came up, and one of them said they hated him because he was a whiny little wanna be, not a good villain like Vader

I told them that they didn’t get it: that was the point of him. Rey explicitly says it. I’m guessing the marketing people didn’t get the memo. To be fair, after I saw the first trailer, I did think “that droid and that lightsaber are going to sell like hotcakes” but once I saw the movie, I knew Kylo Ren wasn’t going to be a commercial force, no pun intended.

BB-8 turned out just fine.

March 14, 2017 @ 10:08 am

Recast Leia…bold…needs to be someone equally iconic…

Oh, wait

Karen Allen.

There. Job done.

March 17, 2017 @ 9:01 am

When we were going to see The Force Awakens we were speculating on what Mark Hamill’s role would be. I suggested it would be a Police Squad style ‘special guest star’ appearance, where he dies in the opening credits before he can speak.

I was almost right.

March 28, 2017 @ 2:20 am

Leigh Brackett doesn’t count as a writer who’d already done better stuff than Star Wars? She worked on the scripts for The Big Sleep, Rio Bravo, and The Long Goodbye