Anything Nasty About The Sicilians (Book Three, Part 27: Skreemer, Shade the Changing Man)

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Peter Milligan made a name for himself in the British market through a series of collaborations with Brendan McCarthy, most notably the banned-from-Crisis comic Skin, about a skinhead thalidomide baby.

“They gave him a silver coffin. They walked behind his coffin, with the Irishers, and Al himself paid for five thousand dollars’ worth of flowers! And after that, if anybody said anything nasty about the Sicilians they said it quiet, and they said it where nobody could hear them talking.” -Neil Gaiman, Violent Cases

It is not entirely clear when Milligan was first tapped by DC. Notably, and unlike other combatants in this phase of the War, DC was not his entrypoint to the American market; he’d published Strange Days with Eclipse back in 1984, and subsequently put out The Johnny Nemo Magazine with them and Paradax with Canadian publisher Vortex Comics. This would have surely meant he was on Berger and Giordano’s radar by the time of the famed February 1987 trip to the UK, where they no doubt met with more writers than just Morrison and Gaiman. In a 1993 interview Milligan described how DC “were asking me to work for the, so I wasn’t going to them. They were phoning up saying ‘Peter you should write something for us. You should do a mini-series, you should do an ongoing series.’” This isn’t entirely incompatible with the idea that Milligan pitched back in February 1987, but it’s notable that his first work for DC, Skreemer, while still a “for mature readers” book edited by Karen Berger in the same basic style as her other imports, did not debut until mid-1989, well after Morrison and Gaiman’s debuts.

But Skreemer stands apart from other first projects by UK imports in other ways as well. Morrison and Gaiman’s first projects were both done according to a very specific template: take an obscure DC character and revamp them, broadly speaking, the same way Alan Moore did Swamp Thing. Even Gaiman’s second project, Sandman, was explicitly set in the DC Universe and at least vaguely connected to an old vintage property. Skreemer, on the other hand, was a standalone miniseries outside of DC continuity. This is always a tougher sell, and to attempt it as a new creator without a proven track record is either an act of hubris or sheer perversity.

This sense continued with the actual content of Skreemer—a violent sci-fi gangster comic told non-linearly and jumping freely among multiple timelines with little indication of sequencing saved for a desaturated color palate on the flashback sequences. This was, in other words, a difficult book. Milligan hs joked that DC “were all keen for writers to be themselves. As long as you were exactly like Alan Moore,” but he was notable as the only one of the initial wave to handle this mandate by trying to work with the structural and narrative techniques of Watchmen, weaving a narrative connected by visual and symbolic transitions as much as by straightforward narrative causality. This is not to say that Skreemer reads like a Watchmen clone, nor even that Moore was Milligan’s primary inspiration in approaching the comic this way—Milligan has made clear that the comic owes a large debt to James Joyce’s famously challenging Finnegans Wake, a connection nodded to both at the outset of the comic, when the narrator introduces himself as Finnegan, and in the concluding issue, literally titled “Finnegan’s Wake.”

The result of this is a comic that by Milligan’s own admission was “a very odd comic. It’s a very strange, intense, very intense, comic. And what’s really strange, I’m finding when I go to—people are kind of like looking at it, like this kind of classic, like this kind of very strange…’my god, Skreemer.’ I read it again recently…I find it more and more—I’m reading it again and realizing it was a very strange—it was a very strange comic.” It is undoubtedly impressive—a fair case can be made that it’s a technically more accomplished and confident debut than either Animal Man or Black Orchid. But it’s a comic that requires a much higher investment from its reader than either of those titles. To do this on your debut with little promotion beyond a DC Direct Currents plug describing it as “a hard-edged, fast-paced series that is at times realistic, at times over the edge of surrealism” is, however, an approach to breaking out as a major talent in the American market that could not possibly work.

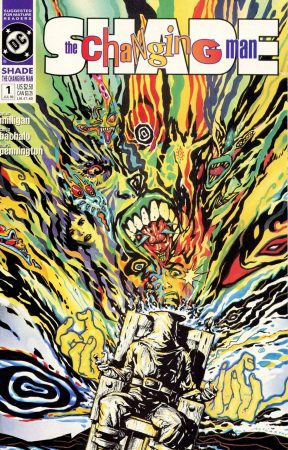

And indeed, it didn’t. Skreemer produced six issues and largely vanished from there, remaining out of print for over a decade before finally getting a trade paperback in 2002 that has long since gone back out of print. It stands as a well-regarded cult classic—a minor work with its ardent devotees, but not a landmark work that shifted the history of comics. In its wake, Milligan disappeared from the American market for the better part of a year before returning with a cluster of projects in mid-1990. The first of these to release was Shade the Changng Man in May, which would both be the iconic work of Milligan’s career and see him correct course and do what sense and prudence would have suggested he do the first time: revamp an obscure DC property for the modern day.

The property Milligan selected for his reboot was Shade the Changing Man, a 1977 comic created by Steve Ditko that was part of the famed DC Implosion the next year. (This event is an oddly seminal one for the British invasion scene, with multiple comics cancelled in this general period or included in the eventual Cancelled Comics Cavalcade ashcan collections to establish copyright on the material eventually getting used for Moore-style revamps, although this is probably simply because it’s a remarkably high density of obscure DC concepts as opposed to out of a specific fondness for the era.) The character was one of several from Ditko’s several year stint at DC in the late 1970s, part of his itinerant later career picking up odd jobs in between his independent work on things like Mr. A.

For those whose preference runs towards Ditko in his most gonzo, Shade the Changing Man is a mixed bag. Ditko drew and plotted issues, but actual dialogue was handled by Michael Fleisher, meaning the comic was never an overt vehicle for Ditko to embark upon lengthy treatises about the virtues of Ayn Rand. Certain underlying themes such as a man seeking to control his reputation within a society of ineffectual bureaucrats feel rooted within Ditko’s beliefs, but this is not the sort of passionate explosion of idiosyncratic belief that characterizes Ditko’s most personal material. All the same, the material appealed to Milligan, who enthusiastically noted, “I really like Steve Ditko, cause he was so fucking crazy. And I liked the idea that — I guess I made it difficult for myself. I couldn’t think of a more absurd and insane character to take on—it was Shade the Changing Man. Because I doubt if you’ve ever read the original Steve Ditko Shade the Changing Man. It’s like, so incomprehensible. It’s really insane.”

Instead the book is a late flourishing of Ditko’s capacity for psychedelic strangeness—an attempt to recapture the weird visual excesses that made his work on Doctor Strange for Marvel so iconic. The eponymous Shade is a former N-Agent from the extra-dimensional world of Meta who, after being framed for treason and imprisoned, escapes to the Earth Zone to clear his name, win back the trust of his partner (another N-Agent, Mellu, who is tasked with hunting him down) and defend the planet from the other escaped Metan criminals. Aiding him in this is a hazily defined device called the M-Vest, which generates a perception-altering force field that means that people around Shade perceive him as weirdly and grotesquely deformed, with a giant asymmetrical head and enlarged fist. Shade has no other powers to speak of (although the force field provided a measure of invulnerability as well), but nevertheless fights off a variety of inventively designed baddies.

The comic was cancelled after eight issues without ever tying into the larger DC universe. Nevertheless he made the obligatory single panel appearance in Crisis on Infinite Earths with every other character imaginable (he’s inexplicably located in New Orleans and teaming up with the equally obscure Prince Ra-Man), and in 1988 John Ostrander revived him for Suicide Squad, having the team run into him while dimension hopping and then work with him for a couple of years before writing him back out by having Darkseid send him back home to Meta.

Just under six months later, Peter Milligan’s take on the character debuted. Unlike what Moore and Morrison did with Swamp Thing and Animal Man, Milligan’s comic was not a straightforward continuation of the original character, who made no further appearances after Ostrander’s use of him in Suicide Squad except in various cameo shots as part of larger tableaus signifying “all the completely forgotten bits of DC lore.” Instead Milligan took the core ideas of Ditko’s series and remixed them into a concept of his own. Rac Shade was still an alien from Meta, still in possession of an M-Vest, and had much of the same supporting cast back on Meta, though they played much smaller roles in Milligan’s version.

The major departure, however, came in the nature of the M-vest and Shade’s powers. In Ditko’s original the M-Vest is the arbitrarily named Miraco-Vest; Milligan, meanwhile, took as his departure point the Area of Madness that existed in the Zero-Zone between Earth and Meta. In Ditko’s original conception this was simply a place that would lead people to scream themselves to death, but Milligan took it as the foundation for the entire character, reimagining the M-Vest as the Madness Vest, which gave Shade never entirely well-defined powers of madness. As Milligan explained it, “I liked the idea of madness almost like a force for change. I heard someone say a really good thing about schizophrenia, that for most people, schizophrenia is a break down, but every now and again it’s a breakthrough. The idea that madness can be a breakthrough.” (This, notably, was adjacent to the concept Morrison sketched out in Arkham Asylum of the Joker as possessing “some kind of super-sanity… a brilliant new modification of human perception. More suited to urban life at the end of the twentieth century,” and for that matter to their handling of Crazy Jane in Doom Patrol.)

The bulk of this, however, went unexplored in Milligan’s first issue of Shade, which instead focuses on a young woman named Kathy George, who is introduced walking back to her hotel room where, she informs the reader in narration, she will murder a man. Kathy is, at least according to her narration, crazy, and as she arrives at the hotel she proceeds to tell the reader just how it was she got to be that way. This turns out to be a somewhat over the top tale of woe, beginning when Kathy and her Black boyfriend Roger goes to visit her parents in Louisiana. Kathy opens the door to their house to discover a man violently butchering her parents. The man attacks her and is tackled by Roger, who is immediately shot in the head by a cop who simply assumes that the Black man must be the problem here. (“It was still the south,” Millign wryly notes in the first of many incisive comments on the US.) All of this prompted a breakdown in Kathy, who spent some years in mental institutions until her inheritance ran out. (“It seemed I was too poor to be crazy,” Milligan notes in another.) Eventually she finds herself standing outside the Louisiana State Penitentiary on the day her parents’ killer, Troy Grenzer, is to be executed. Instead, however, when Grenzer is in the electric chair something inexplicable happens—a strange and psychedelic lightshow that soon explodes out of the penitentary itself as a giant image of an electric chair appears above it and the sky fills with screams and “that cold skeleton laughter you’ve heard since you were a kid, since you were first alone in the dark.” Kathy, standing outside the prison, is assaulted by an electric chair with a disembodied hood with a face, and then moments later finds herself driving her car with Troy Grenzer in the back seat. Except, as it turns out, it’s not Troy Grenzer but a man named Shade, who explains that he’s come from the Area of Madness and possessed Grenzer’s body. [continued]

October 20, 2021 @ 12:14 pm

Madness as a potentially superior form of cognition is a recurring theme in the War. I do hope you’ll get to Moore’s weird conversation-by-fax with Dave Sim at some point; I think it sheds some interesting light on this and related topics.

That said, exploring this concept without coming across as exploitative, dismissive, deeply naive, or just going for cheap thrills is really really hard. And I don’t think Milligan got close with Shade.

I remember when this first came out! I read the first issue and… it left me completely flat. Shade emerging in the body of a serial killer at the moment of execution… was that ever justified? Because at the time, it made my eyes roll good and hard. And while Kathy isn’t a Fridge Girl, most of the first issue is spent on the awful things that happen to this unfortunate young woman. It’s not quite Mark Millar, but there was sadistic undercurrent to it that was off-putting.

I skimmed the series from time to time, and I remember thinking that it felt like a kind of odd anthology — a collection of scattered ideas, some worked out better than others, rather than a coherent story with characters and an ongoing plot. But, tbf, it was 30 years ago and I was skimming, so maybe I missed something.

Anyway, pray carry on.

Doug M.

October 22, 2021 @ 5:18 am

Unpacking Dave Sim, even briefly, sounds like a huge project in itself.

Shade was an unfortunate comic habit that led me to buying X-Men comics by virtue of liking Chris Bachalo’s art

October 24, 2021 @ 10:39 pm

The list of comics I wound up reading because of Chris Bachalo’s art is very long, and does include some very blah X-books, so I feel this.