Erebor (II)

i

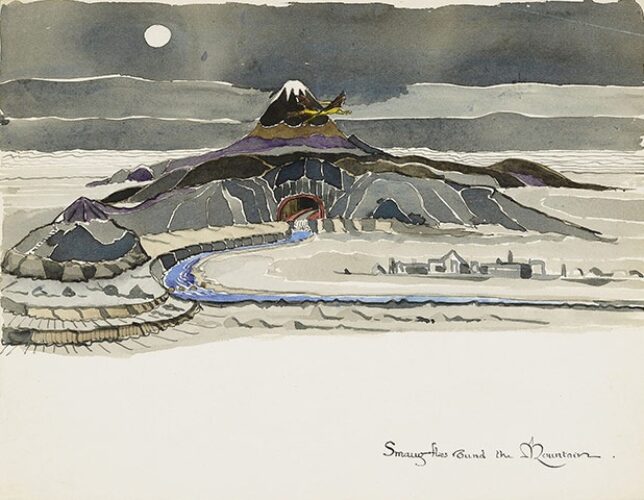

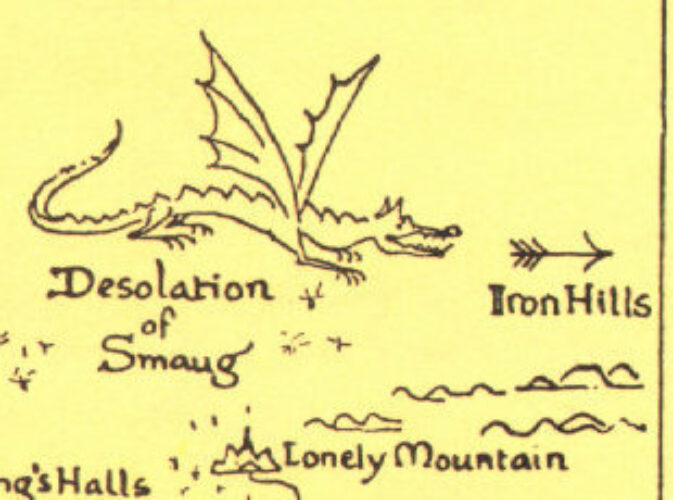

Erebor’s isolation makes it a magical symbol. It hunches over Northern Wilderland like a god of its terrain. Its six spurs reach across its territory like a maimed skulltopus, reaching in every direction, clutching the ground underneath it. Its southern spurs hold Dale like a trinket while Mirkwood watches from an apprehensive distance. Erebor’s power is individualism. What causes more catastrophe in Middle-earth than standing alone?

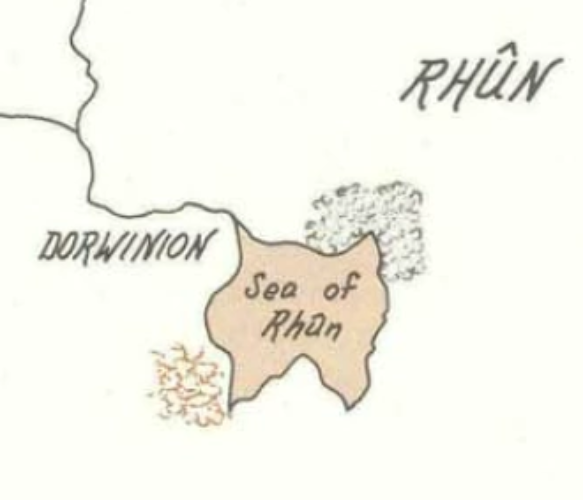

Tolkien’s identity politics are intrinsically geographic. Tolkien assigns territories to individual peoples: the Shire is for Hobbits, Lothlórien is Elvish, Gondor belongs to Númenórean Men. Threatened homelands invariably drive Tolkien’s plots, which often involve the survival efforts of their inhabitants. The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings’s casts are ensembles from numerous peoples and lands who collaborate against a common enemy. Both novels’ denouements involve the improvement of peoples’ and territories’ social and political relationships before everyone goes home to their own peoples. A few characters gain special status among other peoples, like Gimli, the only Dwarf to sail to the Undying Lands, but as ‘exceptions’ they’re nonetheless strictly racially categorized. Otherwise, the Dwarves, who Tolkien considered Middle-earth’s Jews, live outside of the Elves’ resting place.

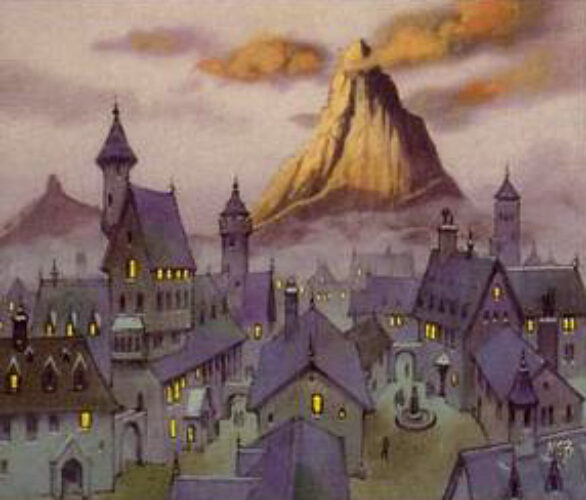

A quintessential racial home, The Kingdom Under the Mountain is the Dwarves’ greatest city, except for possibly Moria, whose sacking is one of their most catastrophic tragedies. A coil of “halls, and lanes, and tunnels, alleys, cellars, mansions and passages” (The Hobbit, “An Unexpected Party”), the kingdom is seen both through Thorin’s nostalgic recaps and as a ruin, a juxtaposition that underlines its effects. But even then, most of it is unseen. The Hobbit’s third act depicts events in only a few halls and cellars. It’s an underground city with some visible edges, not unlike how some of Pompeii’s ruins are still buried. Erebor’s culture is a secret. Its kingdom is every conspiracy theorist’s wet dream: disorientingly grand, ambivalent, intrinisically racial halls of power and commerce.

ii

Past the Front Gate’s “old carven” arch, “a stone-paved road” runs alongside a small channel, which initiates the River Running (The Hobbit, “Not at Home”). At the opposite end, a number of doorways lead to Thrór’s great chamber, which Thorin calls “the hall of feasting and of council”. Its proximity to the Front Gate indicates its stature: visitors will see it before anything else, even if they venture downstairs. It’s where the Dwarves decide and observe significant events. Its designation as Thrór’s chamber points to ancestral pride; the Dwarves commemorate Thorin’s grandfather with this hall.

Thrór is one of Erebor’s pivotal kings, shepherding Erebor’s resurgence after a Dwarvish sojourn from the mountain, driving his people’s return to their kingdom after warring with dragons, and then seeing his kingdom destroyed by a dragon. Over 300 years before Thrór’s birth, his ancestor Thorin I leaves Erebor to mine the “rich and little explored” Grey Mountains, “where most of Durin’s folk were now gathering” (The Return of the King, Appendix A: “Durin’s Folk”).…