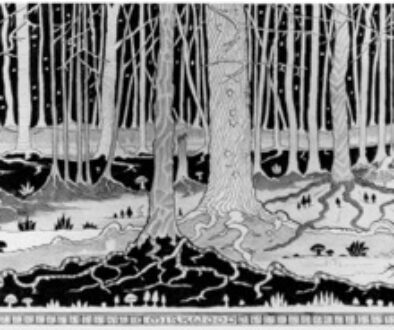

Dorwinion

Book II of Nowhere and Back Again begins here.

“It has long been said that the desert is monotheistic. Is it illogical or devoid of interest to observe that the district in Paris between Place de la Contrescarpe and Rue de l’Arbalète conduces rather to atheism, to oblivion and to the disorientation of habitual reflexes?”

— Guy Debord, “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography”

Names: Dorwinion or Dor-Winion (Sindarin for “Young-land country”, according to Tolkien)

Descriptions: Dorwinion lies on the Sea of Rhûn’s northwestern shore. Little is known of it beyond its vicinity to the River Running, which it uses to deliver some powerful wines to Rhovanion, particularly in Mirkwood, where the Silvan Elves get positively zonked on it. The wine is the only thing people know Dorwinion for, really. It seems to have had a brief tenure as a Gondor territory during the Third Age, which lasted as long as any pre-War of the Ring Gondorian conquest.

The next step of our adventure takes us into Rhovanion, or Wilderland as the Hobbits

call it, the massive, disparate and heavily populated but wild, rocky and deserted region of northeastern Middle-earth. It lies north of Mordor’s Ash Mountains, west of Rhûn, south of the enigmatic Northern Waste and its Grey Mountains, and east of the Misty Mountains and Eriador beyond them, Middle-earth’s relatively green and peaceful northeast haven. This makes Rhovanion landlocked, with the inland Sea of Rhûn the one significant body of water in its vicinity, from which runs the River Carnen to the north, where it meets the Iron Hills, and the River Running, which flows to the west, into the seemingly endless forest of Mirkwood. Mirkwood runs 600 miles from the north, just below the Grey Mountains, to the south, near the Brown Lands and Emyn Muil. To its west lies the Anduin, the Great River of Middle-earth, along which lie the Vales of Anduin, the elven haven of Lothlórien, and the residences of many foes, orc, Istar, elf, and Beorning alike.

Unlike Mordor, which is wholly ruled by Sauron, Rhovanion is lawless, with enigmas both from Valinor and from its own dark crevices, with no central authority or ruling citadel. Compared to Mordor’s monoculture of slavery and theocratic rule, Rhovanion shows us a multicultural and multiracial region (or macro-region, as Rhovanion homes many small regions), which gives us a look into the lives of more Peoples of Middle-earth. Tolkien sets many sequences of his most popular works here; Rhovanion is host to most of The Hobbit’s plot, and the latter stretches of The Fellowship of the Ring. We have far more information on Rhovanion than we do on Mordor; The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings’ appendices contain ample reports on its history. In short, it is a storied region, more ambiguous and varied in its geographic and cultural terrain than northern Mordor, where the conflicted interests of diverse peoples collide and change history. Wilderland shows us a path through light and darkness, one with no clear end in sight and no champion in the outcome. The Hobbit’s Battle of Five Armies shows Rhovanion at its breaking point, a truly weird land breaking itself apart. Let us hope our journey across its extensive battlefields will spare our hearts and minds.

Our path through Wilderland begins on the Sea of Rhûn’s northwest shores, in Dorwinion, a remote land known as Middle-earth’s vineyard. Its history involves its fleeting conquest by Gondor in the Third Age, followed by its reclamation by the Wainriders, a vagabond warrior people, its ravaging by plague, and eventual commerce with Rhovanion and particularly the Woodland Realm, the Silvan Elves’ kingdom in Northern Mirkwood. As Dorwinion is significant for its wines, its brew is its major cultural export. And apparently ”the heady vintage of the great gardens of Dorwinion,” is pretty potent stuff, which “brings deep and pleasant dreams” (The Hobbit, “Barrels Out of Bond”). It’s strong enough to knock out a Wood-elf, which is quite a feat as “it must be potent wine to make a wood-elf drowsy” (in Peter Jackson’s The Return of the King, Legolas and Gimli play a drinking game that eventually causes an inebriated Gimli to pass out while Legolas feels only “a slight tingle in [his] fingers”). This is the lowest instantiation of fantasy storytelling, something that people do in everyday life played with extra potency and mystery. It’s certainly an alluring detail; as a lightweight who can barely hold my wine and who breaks into anaphylactic shock whenever I drink hard liquor, I can look at the Wood-elves passing out and think “they’re just like me!”

Wine shows a curious side of the Woodland Realm’s infrastructure, and how the Wood-elves’ commerce with Men works. Mirkwood cannot carry out its own winemaking, as “no vines grew in those parts,” so the Woodland Realm partly relies on Dorwinion to supply it with wine. (The Hobbit says that the Wood-Elves also get wine “from their kinsfolk in the South,” possibly Lothlórien). To receive Dorwinion’s offerings, Mirkwood has a recycling program in conjunction with Lake-town to its east. The wine is sent up in barrels the Long Lake to Lake-town, from which the barrels are brought up the Forest River to the Woodland Realm, where “often they were just tied together like big rafts and poled or rowed up the stream,” or simply “loaded onto flat boats”. Once the Wood-elves have imbibed the mystery vino, they expel the barrels through trapdoors in their cavernous cellars, so “out the barrels floated on the stream, bobbing along,” until the river’s current brings them to the borders of Mirkwood, where they’re collected and floated back to Lake-town. (Tolkien does not say whether any money changes hands in this process; Elvish economy is barely glimpsed through other parts of The Hobbit). Bard the Bowman, the dragon Smaug’s eventual killer and another one of Middle-earth’s disenfranchised heirs, is seen performing this duty in The Desolation of Smaug, where he occupies a dogsbody-like role compared to his role as a soldier in the book (both suggest a fall from grace for his ancestors, but one role indicates a militaristic stature, while the other renders Bard an ancestrally disgraced worker). He does not interact with the Wood-elves at this point — it doesn’t appear that he’s met any Elves before his encounters with them in The Battle of the Five Armies. If anything, this shows that Lake-town performs waste management for Mirkwood — handling its scraps with cyclicality and care, but presumably not receiving much of that powerful Dorwinion wine in return.

While the Lake-town men lead presumably temperate lives, the Wood-elves keep masses of Dorwinion wine in their cellars. Yet even with these endless stores, it seems not all wines are afforded to all Wood-elves. The Dorwinion stuff is reserved for the Elven-king Thranduil, and is “not meant for his soldiers or his servants, but for the king’s feasts only” (which sounds like Thranduil telling his people “no guys, only *I* can handle the wine that fucks you so badly you think the shit in your britches is liquid death”). This doesn’t prevent some delinquent Wood-elves from sampling the wine, though, as the king’s butler and chief of the guards drink some, ostensibly to “see if it is fit for the king’s table.” Dorwinion wine proves more fit for a king’s table than a cellar table, though, as the butler and chief guard find themselves unconscious pretty quickly when they drink the forbidden booze. When Bilbo Baggins uses the cellar’s trap doors to evacuate his Dwarf companions from Thranduil’s realm, he’s able to steal the dungeon keys from an inebriated and unconscious chief guard, who sleeps beside his butler friend (once he’s freed his companions, Bilbo thoughtfully returns the key to the chief guard’s side to prevent him from getting in trouble with his king). Tolkien couldn’t write a better advertisement for Dorwinion’s vineyards if he tried.

Yet the homeland of this elf-zonking booze is a mystery. Tolkien never concluded who lived in Dorwinion, and its location appears to have been a late decision on his part. It was absent from Tolkien’s Beleriand maps, and also the maps in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Its first appearance is in illustrator Pauline Baynes’ 1970 Middle-earth map, its inclusion a request from Tolkien, although in The History of the Hobbit, John D. Rateliff notes that on Baynes’ map Dorwinion is “no further south” than Dol Guldur, which likely pits its location against Tolkien’s intentions when he wrote The Hobbit. While Dorwinion is certainly adjacent to the Sea of Rhûn, its precise nature can only be deciphered through the broader mythology.

As Rateliff shows, The Hobbit was more in line with the 1930 Quenta Silmarillion than its historical reputation, despite Tolkien’s later insistence that The Hobbit was developed independently of his mythology. (Elrond and the Wood-Elves and references to Gondolin and Durin show this, as well as an early redacted reference to The Silmarillion’s legendary man-elf couple Beren and Lúthien). Despite its nebulousness, Dorwinion appears in Tolkien’s mythology at its earliest stages, such as in 1918 or slightly later’s “The Lay of the Children of Hurin,” where Túrin Turambar and his companions drink the potent wine, and “their heads were mazed / by the wine of Dor-Winion [sic] that went in their veins, / and they soundly slept on the soft needles / of the tall pine trees that towered above” (The Lays of Beleriand, “The Lay of the Children of Húrin”). Tolkien wrote that Dorwinion was one of three untranslated names in The Hobbit, and the one Sindarin name in the book, meaning “Young-land country’. John Rateliff shows that this would etymologically connect Dorwinion to the Celtic mythic Tir na nÓg, which appears in Tolkien’s 1924 poem “The Nameless Land,” which speaks of a paradisal place “where no man may be!” (The Lost Road). The name also appears in the 1937 Quenta Silmarillion to refer to Valinor’s vineyards, which Rateliff says likely means that “Tolkien simply re-used this name” after its chronological writing in The Hobbit.

So the tide of Tolkien’s maps ebb and flow with his philology. This is no secret; Tolkien’s mythology grew out of the Old English word “Earendel” from the poetic compilation Christ I. To decipher Tolkien’s words on a map, they must first be understood through etymology and linguistics. Rateliff observes that Tolkien binds the Mirkwood elves with elves from Doriath, Beleriand’s Sindarin kingdom in the First Age, since “such wine appears in only two of Tolkien’s works, … and both times in connection with the wood-elves” (The History of the Hobbit, “In the Halls of the Elvenking”). And as Dorwinion is the lone Sindarin name in The Hobbit, its name for the vineyards from which elves imbibe wine that gets them totally zonked invites the audience to interrogate who lives there.

So who lives in Dorwinion? Michael Martinez has some good guesses, as guessing is the best we can do here. Tolkien doesn’t really say; he deemed “its Sindarin name a testimony to the spread of Sindarin,” which suggests Dorwinion merely has an Elvish name without necessarily being an elven kingdom. The Hobbit doesn’t help matters much, saying the Wood-elves’ wine is “brought from far away, from their kinsfolk in the South, or from the vineyards of Men in distant lands.” Either description could fit Dorwinion, which certainly lies south of the Woodland Realm but can also be classified as a “distant land”. Rhovanion’s diversity is one of its staples; it’s home to many peoples, including elves and men alongside other folks. Surely Dorwinion reflects that.

Maybe someday the Tolkien Estate will unearth a draft where Tolkien elaborates on Dorwinion. Yes, it’ll say, Dorwinion is populated by orcs. They’ve made peace with the Eldar, who bless their lands and give them some wine-making tips. The graceful Dorwinion-orcs improve on the process, using some of the Elvish magic when they ferment their wine. A happy-go-lucky orc will tip his gardener’s hat to a passing orc-maid before taking a drink. The orcs of Dorwinion are merry as they privately celebrate their Vala father Melkor, who gave them life, while living peacefully in their own land and receiving a pretty penny for their wines.

We will probably never read more of Tolkien’s winemakers. They exist as throwaway lines and details on a map; they enrich Tolkien’s mythology by adding ambiguity and a sense of a world beyond his perspective. But let’s have fun: let’s call Dorwinion-folk merely “Rhovanion-folk”: if Tolkien was interested in their stories, he would have written them, or meant to write about, take some notes, and forget about the matter for 33 years. Either way, Dorwinion makes its mark on Middle-earth: when elves are trashed, something magical and unrecorded is at work.

August 20, 2021 @ 1:48 pm

Their potency makes the wines of Dorwinion ideal for drinking contests, in which, as is customary, competitors are eliminated as they lose consciousness or are left otherwise unable to continue drinking, until one alone remains as the victor.

This is known as

Dorwinion natural selection.

August 20, 2021 @ 3:53 pm

BOOOOO

August 20, 2021 @ 2:56 pm

The stitching into the picture of the Wood-elves of elements drawn from Doriath reaches a surprising degree of closeness with the adaptation of the story of the Necklace of the Dwarves (but without the king’s death). It leaves the story as published in a strange, ambivalent spot which is neither its apparent early conception as taking place not only in the same world but in the same era as The Silmarillion, reflected in that extraordinary reference to Beren and Luthien, nor its eventual placement as part of the same world but much later. The separation in time is already there, but the world shifts out of focus, reframing strands of the existing mythology in a way that sits oddly with its being straightforwardly part of the same history.

The elvish economy may be barely glimpsed, but I think The Hobbit gets us as close as we ever do in Tolkien to a recognition that elves require any kind of primary food production at all, outside of apparently limited and semi-recreational hunting. The Wood-elves may not “bother much with trade or with tilling the earth”, but at least it suggests they may till a little, even if it leaves us in the dark as to how such activities remain so apparently discretionary, to be “bothered with” or not. The necessary drudgery of food production is a point where Tolkien never quite brought himself to impose the implications of the concrete materiality of his elves onto the more fantastical source-traditions of the fairy.

December 17, 2021 @ 7:01 am

It turns out that I overstated the totality of this – the verse Children of Hurin mentions cultivated fields and orchards around Nargothrond.

August 20, 2021 @ 3:04 pm

I don’t think any of the Wainriders’ conquests can be classed as a reclamation, unless one treats the peoples of the East as an undifferentiated mass, to a greater degree than Tolkien does.

August 27, 2021 @ 7:24 am

It’s always stuck me as amusing that the Wainriders, both in what we know of their society and geography (if Mordor is Hungary and Rhun the Black Sea, then Rhovanion is the steppe) are a pretty good match for the Proto-Indo-Europeans as per Gimbutas’ Kurgan hypothesis. And of course the Wainriders are some of the Easterlings under Sauron’s influence.

Someone better versed in the history of the field of Indo-European historical linguistics and Tolkienology might know whether this is anything other than a coincidence, but I can imagine that he’d be aware of these ideas long before they hit the mainstream.

August 27, 2021 @ 7:40 pm

In terms of historical parallels, the Wainriders map most closely onto the Huns (invading nomads from the east who conquer Germanic-speaking people with Gothic names inhabiting the great plains of eastern “Europe” and precipitate a westward migration of many of those people to escape them, subsequently clash with the “Romans” and suffer a great downfall through defeat at the latter’s hands and a major revolt of their Germanic subjects), and perhaps also the Avars (nomads of similar sort who subsequent to these events carry out a devastating but ultimately unsuccessful combined assault on the “Romans” in conjunction with “Middle Eastern” allies).

I think Hungary maps best onto Rohan, the great mountain-fringed plain inhabited by horse-people which is located to the north of core “Roman” territory and was at one time wholly or partially under “Roman” rule, is separated from the far wider steppes to the east by a major natural frontier, and is grouped within “the West”. The plains of Rhovanion are roughly the European sreppe, Rhun the Asian steppe, and the Sea of Rhun the Caspian. Mordor sits outside of the loose analogue of early medieval history going on in the surrounding lands, but geographically is a kind of weird fusion of Anatolia and the Black Sea.

August 28, 2021 @ 3:30 am

I understood that the Yamnaya had carts & chariots but not mass horse-riding (because the horses were still too small before centuries of breeding would make them big enough to ride) which is what stood out to me because they’re specifically called ‘wain’riders and not ‘horse’riders.

It struck me as either an amusing coincidence or interesting choice in view of how much is read into Tolkien’s racial views that you could see this match between a group that’s so ancestral to Europeans and a culture that’s under the sway of darkness in his stories.