Erebor (I)

Names: Erebor (Sindarin: “ereb”: lonely, isolated, “-or”: rise, mount), glossed as “the Lonely Mountain”

Description: A solitary mountain in northern Wilderland. Karen Wynn Fonstad estimates Erebor’s summit as 3500 ft (1066.8 m.) while at its broadest spurs its furthest reaches are about 9 mi. apart (approx. 14 km). The Lonely Mountain has six spurs, between the southern and southeastern of which originates the River Running, which flows through Dale, a city of Men. Home to the Longbeard Dwarves’ Kingdom under the Mountain, Erebor encompasses formidable mines, cellars, and throne rooms.

In T.A. 1999, Thráin I, a dwarf refugee from Khazad-dûm, arrives at Erebor and establishes the Kingdom under the Mountain. Dwarves begin mining Erebor, and collect gems and gold, including the Arkenstone (the Heart of the Mountain). The Kingdom under the Mountain prospers King Thrór, as the dwarves of Erebor arm the Iron Hill Dwarves and Wilderland’s Men against Easterlings.

In 2770, the dragon Smaug sacks Erebor, killing and dispersing the dwarves. He occupies the Mountain until 2941, when Erebor’s exiled king Thorin Oakenshield arrives at the Mountain with a small party. In retaliation, Smaug destroys Lake-town, a local settlement of Men, where Bard the bowman kills him. In the wake of Smaug’s demise, the Maia Sauron sends orc forces to conquer Erebor. The dwarves and their Iron Hills cousins fight in the Battle of the Five Armies. They triumph, though Oakenshield is killed. His successor as King is his cousin Dáin II Ironfoot.

In 3019’s Battle of Dale, Easterlings besiege Erebor and kill Dáin. They retreat when Barad-dûr falls. Thorin III Stonehelm is crowned King under the Mountain, and establishes a relationship with Gondor’s King Aragorn II Elessar, after which Erebor comes under Gondor’s protection.

Location in Peter Jackson’s films: Wanaka, Otago, South Island.

“I see the mountain/That is all I see.”

Carter, “The Mountain.”

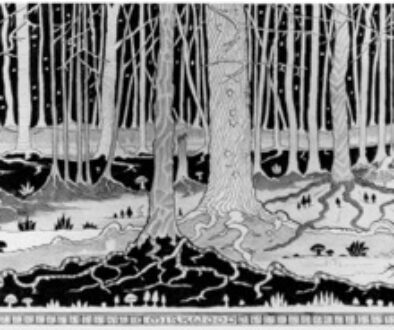

This adventure began on a mountain. Now it arrives at another one, also solitary, hospitable yet apocalyptic when it chooses to be. The Lonely Mountain changes hands and talons many times, and yet its six spurs, summit, and cavernous interiors belong to no person. The Kingdom under the Mountain is not the Lonely Mountain itself; it’s an occupying force that the Mountain permits to dwell in its guts. Smaug scorches the earth around Erebor, the Lonely Mountain, strengthening its mighty power over Wilderland. Guy Debord says that psychogeography is “the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographic environment, whether consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behaviors of individuals” (“Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography”). Some of Tolkien’s most memorable characters are seismically changed and affected by Erebor. The shaking of windows or rattling of walls has little sway on the Mountain’s power; people may only submit to it.

Erebor is one of the most haunting places in Tolkien’s mythology and a corridor to many of its crucial themes. It’s an anti-realist landmark; Tolkien’s geography has little quarter for geologic reality, a recurring aspect of his mythology that Alex Acks has analyzed in depth. Middle-earth’s landscapes are a surrealistic space of signifiers and communities where epochs and theodicies slowly fight to the death in spaces perfectly designed for them. Even in its sacked and demolished state in The Hobbit, Erebor has a functioning (abandoned) infrastructure. Its secluded eastern passage is completely untouched, and Smaug’s avarice preserves Erebor’s wealth. The Front Gate’s ruined bridge rights itself, as “most of its stones were now only boulders in the shallow noisy stream; but [Bilbo, Balin and company] forded the water without much difficulty” (The Hobbit, “Not At Home”). Tolkien’s world lives in a permanent state of planned atrophy; it contains a core of Catholic hope: a conviction that Someone great watches over the world.

Erebor is something of a guardian, as its Kingdom is the ruler (if you will) for measuring Middle-earth’s politics and economy. The dwarf-realm makes “things of wonder and beauty”, including “weapons and armour of great worth”, which facilitate “great traffic of ore between [the Erebor dwarves] and their kin in the Iron Hills (Appendix A, Durin’s Folk). In the Kingdom’s heyday, economic prosperity leads to Northmen defending the River Running and Redwater from marauding forces, keeping Erebor secure and uninvaded. These riches seduce Smaug; the Dwarves’ penchant for excessive mining often undermines their prosperity with apocalyptic results. The Dwarves inevitably rebuild their lives and repopulate their lands, and either relapse into their worst tendencies or forge a better future. Yet the future has limits; Arda’s cosmogony makes Dwarves, illicitly created by the Vala Aulë, and thus lesser beings than Elves and Men, the Children of Ilúvatar, the Dwarves’ victories and falls are relegated to lesser importance. As with history, Tolkien’s mythology is a cyclical, unending saga of triumphs and follies paying each other off.

As a testament to triumphs and follies, there is the Lonely Mountain’s Front Gate. It’s positioned between the south and southwestern spurs, towards its neighbor Dale. The River Running originates “out of a dark opening in a wall of rock” which flows through a carved channel and then down into the valley below, apposed with “a stone-paved road”, at the end of which is the Front Gate, a “tall arch, still showing the splinterings of old carven work within, worn and splintered and blackened though it was” (The Hobbit, “Not At Home”). The stream at the bottom which turns into the River Running is shallow, and easily crossed by a bridge (demolished by The Hobbit’s time). Balin estimates that the Gate is “five hours’ march” from Ravenhill, the southwest spur’s watchtower, which places Dale and Lake-town at a not-inconsiderable distance from the Kingdom under the Mountain. This also has the effect of putting various townships between Erebor and potential invasion, thus securing the Mountain’s dwarves from all but the most robust armed threats.

If the Front Gate is where hope lives, it’s a battlefield of fraught, attenuated hope. The Gate shapes its inhabitants’ experiences, but it by no means directs their morality. It’s where Smaug enters the Kingdom and massacres the dwarves. Thorin and Dáin are killed at the Gate, where swaths of the Battle of Five Armies are fought. Thorin’s fall from grace happens at the Gate, where he rejects Bard’s plea for reparations and attempts to murder Bilbo. But the Front Gate’s catastrophes are often redeemed by love and grace: Thorin repents on his deathbed, Fíli and Kíli sacrifice their lives for their uncle, Dáin rejects dwarf-rings from a Ringwraith, and the dwarves and the Bardings are permitted to continue living in their mountain. Erebor’s Front Gate serves as a backdrop for some of the great moral decisions in The Hobbit and important offstage events in The Lord of the Rings. Thorin and Dáin have to make their decisions because of their place at Erebor’s gate, and yet they come to radically different conclusions about how to utilize their power and status.

Thorin is one of Tolkien’s tragic heroes whose motivations are initially noble and are slowly warped towards sinister and myopic ends. He embodies some of Tolkien’s most frequent archetypes: a dispossessed vagabond descended from lords whose moral fall caused great catastrophe, a dwarf whose obstinate independence and avarice undermines other people’s safety, and an initially well-meaning lord who falls prey to his own worst instincts. Thorin presents a unique variation on the theme though; his motivations don’t really change. At the beginning of the book Thorin wants to reclaim Erebor and reignite his Kingdom, and when he’s accomplished that, he keeps reigniting his kingdom. The context changes how his actions affect people; when he reneges on his promise to reimburse Lake-town, particularly after causing Smaug to burn them, his previously honorable goals become monstrous and cruel. See how Thorin talks about the Lonely Mountain’s days of greatness at the beginning of The Hobbit, where unlike the other dwarves he is “very haughty and said nothing about service”:

“Kings used to send for our smiths, and reward even the least skilful most richly. Fathers would beg us to take their sons as apprentices, and pay us handsomely, especially in food-supplies, which we never bothered to grow or find for ourselves. Altogether those were good days for us […] So my grandfather’s halls became full of armor and jewels and carvings and cups, and the toy-market of Dale was the wonder of the North.”

The Hobbit, “An Unexpected Party”

Thorin also seems to have some survivor’s guilt, as he describes himself as among “the few of us that were well outside” when Smaug came to Erebor, as Smaug

“crept in through the Front Gate and routed all the halls, and lanes, and tunnels, alleys, cellars, mansions and passages. After that there were no dwarves left alive inside, and he took all their wealth for himself.”

As Erebor’s wealth is lost, Thorin has lost his dignity. He has become a workman, resentfully telling his party at Bag End that “we have had to earn our livings as best we could up and down the lands, often enough sinking as low as blacksmith-work or even coal mining.” A contemporary reader might raise an eyebrow at Thorin’s disparagement of manual labor here, but let’s remember that the dwarves are continually dispossessed. When Moria and Erebor fall, their former inhabitants are forced to live dangerous lives as unhomed and impoverished workers. Poverty sucks, and not knowing where your next meal will come from is exacerbated when you once expected to be the King under the Mountain. Here Tolkien’s use of Jewish people as a model for his dwarves shows a more sympathetic side to his understanding: a deep sorrow for the struggles and dispossession of a continually persecuted people.

The Hobbit films mostly communicate Thorin’s strong leadership of his party through conversations with Balin. It’s Balin who regales Bilbo about Azanulbizar, and in an earlier scene at Bag End Balin attempts to dissuade Thorin from trekking to Erebor by telling him “you have done honorably by our people.” Tolkien provides a broader portrait of Thorin’s years between Azanulbizar and his return to Erebor. When his father Thráin, haunted and perturbed by his Dwarf-ring (the last of the Seven), leaves his people at the Blue Mountains to reclaim Erebor, an aborted quest that ultimately leads to his death in Sauron’s hold at Dol Guldur, Thorin’s initial action as Durin’s Heir is to remain where he is:

So Thorin Oakenshield became the Heir of Durin, but an heir without hope. When Thráin was lost he was ninety-five, a great dwarf of proud bearing; but he seemed content to remain in Eriador. There he laboured long, and trafficked, and gained such wealth as he could; and his people were increased by many of the wandering Folk of Durin who heard of his dwelling in the west and came to him. Now they had fair halls in the mountains, and store of goods, and their days did not seem so hard, though in their songs they spoke ever of the Lonely Mountain far away.

This account of Thorin’s actions, written long after The Hobbit, contrasts with the Thorin of that book, who seems eager to escape from his impoverished life as a disgraced heir. The discrepancies in character, tone, and plot between The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings have been noticed by every reader who’s read both books; Tolkien’s revisions of The Hobbit, particularly his aborted attempt in 1960 to rewrite the book wholesale, are indicative of just how disparate The Hobbit and its sequel are. Ever the completionist, Tolkien worked to reconcile his books up until his death, and yet this gulf between two seemingly different Thorins remains an oddity. Thorin’s role as a pompous dwarf-lord craving to reclaim his birthright clashes with his apparent reluctance to leave the Blue Mountains, where Thorin and Thráin before him settled. Perhaps we can infer that Thorin both desires to return to the Mountain and fears it deeply. An Unexpected Journey lampshades the difference by having Thorin be a wise and successful leader of his people who’s also aching to retake Erebor. If we were to make connections between the two portrayals in Tolkien, it could be inferred that Thorin is afraid of following in his father’s footsteps and just as terrified of seeing the Lonely Mountain and Smaug again. The Mountain is both his redemption and his killer. The dichotomy is enough to make anyone mad; when trauma meets semiotics, the results break worlds.

When Thorin regains his Kingdom, he rejects his humiliation by Thranduil in particular, but also his perceived humiliation by Gandalf and Bard. The Mountain amplifies his suspicions: the dragon-sickness caused by Smaug’s claim on Erebor’s gold overtakes Thorin’s mind:

But also [Bilbo] did not reckon with the power that gold has upon which a dragon has long brooded, nor with dwarvish hearts. Long hours in the past days Thorin had spent in the treasury, and the lust of it was heavy on him.

The Hobbit, “The Gathering of the Clouds”

Alarmingly, the book makes Thorin’s failure to assist his neighbors both a moral failure and a consequence of his dwarvish ancestry. Tolkien’s dwarves are modeled after Jewish people, and the comparison invokes deeply troubling antisemitic tropes. Like Shylock in The Merchant of Venice, Thorin must execute the villainy the world teaches him. While Tolkien carefully imbued his characters with free will, wrestling with the paradox of agency in a place where people’s characters are genetically determined, he never got past the basic hurdle of inherent racial characteristics. The nature of Tolkien’s racial cosmogony means that Thorin has to turn villainous. Regardless of his opponents’ motivations (Gandalf, Thranduil, and Bard are hardly malevolent), Thorin is simply cornered by his circumstances. Even Thorin’s attempted murder of Bilbo boils down to grief and horror at his friend giving away the Arkenstone, the diadem of Erebor’s jewels:

“By the beard of Durin! I wish I had Gandalf here! Curse him for his choice of you! May his beard wither! As for you I will throw you to the rocks!” he cried and lifted Bilbo in his arms.

The Hobbit, “The Clouds Burst”

“Stay! Your wish is granted!” said a voice. The old man with the casket threw aside his hood and cloak. “Here is Gandalf! And none too soon it seems. If you don’t like my Burglar, please don’t damage him. Put him down, and listen first to what he has to say!”

“You all seem in league!” said Thorin dropping Bilbo on top of the wall. “Never again will I have dealings with any wizard or his friends. What have you to say, you descendant of rats?”

Thorin’s motivations have remained the same, except they’re now contrary to the other characters’ desires. When Dale burns and Thorin refuses to help its people, his motives become sinister to them. He has the wrong virtues (and thus the right vices) for the situation. The Lonely Mountain, which is Thorin’s redeemer in some ways, also becomes his killer. Middle-earth’s lands fall when its kings fail, yet the relationship is not causal: it is recursive and symbiotic. Thorin’s fate is bound with Erebor’s; when he fails, he must be sacrificed in order for the Kingdom to survive.

This symbiosis grants Thorin a redemptive death. He ends his legacy as a war hero in the inverse of Azanulbizar: the dwarves keep their homeland because they collaborate with other peoples, and Thorin’s tenure as curator of Durin’s line is done. As he tells Bilbo, “I go now to the halls of waiting to sit beside my fathers, until the world is renewed” (The Hobbit, “The Return Journey”). Having made peace with Bilbo and his people, Thorin’s time as Erebor’s subject ends, and Dáin Ironfoot’s more peaceful relationship with the Kingdom resumes.

New Line Cinema’s The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies alters Thorin’s death significantly. The introduction of Azog to the story gives Thorin a final duel with an old foe not at the Front Gate, but at Ravenhill, Erebor’s abandoned outpost on its southwest spur. In both the book and the film, Ravenhill is where Bilbo and the dwarves camp upon their arrival to Erebor, while in the novel alone it’s the primary outpost for Bilbo, Gandalf, and the Mirkwood Elves. Thorin’s death at the Front Gate is a death among his people, a glorious match in battle. By transplanting his last stand to Ravenhill, the film accommodates Richard Armitage’s portrayal of Thorin: a solitary warrior who wanders off on his own, particularly once he reaches Erebor, and faces doom alone. Armitage plays Thorin as particularly aloof and traumatized, tapping into a queer side of the character who’s subtextually in love with Bilbo. Ravenhill puts him at a remove from everything: he dies, an elderly veteran combatting his old enemy, alone, with only his love Bilbo present at the end.

Oftentimes in Tolkien’s work, distance between a person and power is the ultimate redeemer. Frodo is appointed Ring-bearer because his lack of cultural or spiritual connection to the One Ring puts him at the greatest remove from it (and it still defeats him). As we’ve previously discussed, Dáin Ironfoot’s isolation in the Iron Hills insulates him against corruption. He assists his family when necessary, but avoids their foibles by staying alone. Even though his killing of Azog at the Battle of Azanulbizar wins the battle, he stays away from Moria, telling Thráin

‘You are the father of our Folk, and we have bled for you, and will again. But we will not enter Khazad-dûm. You will not enter Khazad-dûm. Only I have looked through the shadow of the Gate. Beyond the shadow it waits for you still: Durin’s Bane. The world must change and some other power than ours must come before Durin’s Folk walk again in Moria.’

Another possible analogy between dwarves and unfortunate Catholic ideas of Jews sneaks in here: Dáin doesn’t personally know the holy powers that will kill the Balrog, but he’s wise enough to recognize they exist. The soteriological limits here are alarming, not least because they make Dáin “one of the good ones,” but they also help make Dáin one of Middle-earth’s most complex dwarves. Dáin mirrors Thorin: both lose their fathers, while Dáin’s choice is to stay away from more trauma for his people. His presence at the Battle of Five Armies is a sign of severe danger: Ironfoot avoids the Mountain until he absolutely cannot do otherwise. Like most dwarves, he’s secluded, but the major dramatic beats of his story entail coming out of his shell.

Dáin rejects power for the Dwarves several times: spurning Moria, not returning to Erebor until his people need him to rule, and rejecting a Ringwraith’s offer of the three remaining Dwarvish Rings of Power at the Front Gate. His actions keep Erebor independent but beholden to outside powers, and more or less preserve the Kingdom from utter ruin. In another one of the Front Gate’s tense confrontations, a Ringwraith offers Dáin a choice between “three rings that the Dwarf-sires possessed of old shall be returned to you, and the realm of Moria shall be yours for ever” in exchange for returning the One Ring to Sauron, or refusing and “things will not seem so well” (The Fellowship of the Ring, “The Council of Elrond”). Dáin is not overcome by greed the way Thorin was, as he chose to come to the Mountain, while the Mountain was Thorin’s life, diplomatically telling the Nazgûl “I say neither yea nor nay. I must consider this message and what it means under its fair cloak.” Unlike Thorin, Dáin delays war as long as he can, and saves Bilbo’s life with his words at the Front Gate.

But no dwarf survives the Lonely Mountain; the lands live longer than people ever will. Like Thorin, he is killed at the Front Gate, this time by Easterlings in a temporarily successful siege of Erebor. Yet as he predicted at Moria, some other power than his comes along and disperses his enemies. Is it the power of Ilúvatar and the Ainur? In part, but indirectly. The Lonely Mountain has a will of its own; the lands of Middle-earth direct the people who live in them, even as their geography and topography are etched around their stories. The game of Middle-earth and its lands is symbiosis: its lands and its people are one, and yet the lands always win. The Front Gate is where the Lonely Mountain’s powers eke into the world, where its desperate solitude overtakes all. What lies in the Mountain’s entrails is a far deeper and stranger power.

January 7, 2022 @ 6:43 am

Another great entry, really glad to see this series back. I remember, back when I was a kid playing the 2003 Hobbit videogame, longingly staring at the conical peak of the Lonely Mountain, visible in the gloomy purple nighttime skybox for the Lake-Town level. It gave me such a strange mix of wanderlust and trepidation, that few other experiences could quite capture (Morrowind being one that springs to mind). The way the mountain is personified really speaks to Tolkien’s intense focus on the natural landscapes in his stories.