Breeding, Darling (Book Three, Part 23: Drivel, Steed and Mrs. Peel)

CW: Sexually explicit imagery

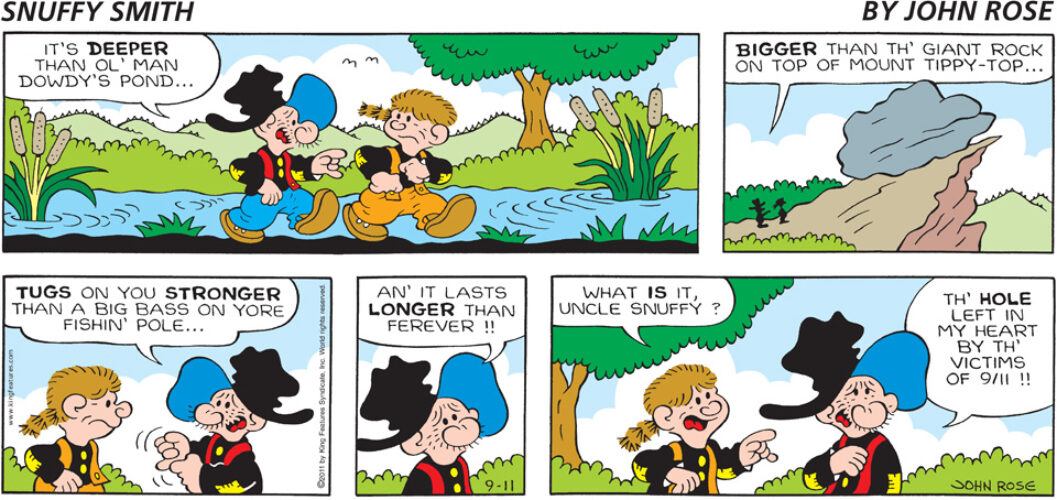

Previously in The Last War in Albion: The comics/pop culture magazine Deadline proved one of the most successful publications of the early 90s British comics renaissance on the back of the massively popular Tank Girl.

“What makes you such a bitch, Emma?”

“Breeding, darling. Top class breeding.” -Grant Morrison, New X-Men

Initially the character took off in the British queer scene—Tank Girl made a number of appearances in anti-Clause 28 protests. Deadline editor Dave Elliott successfully got the magazine US distribution under Dark Horse, who launched it in 1991, just in time to catch on with the emerging riot grrrl scene, where it took off, making Tank Girl into a latter day feminist punk icon. One of its fans was the stepdaughter of director Rachel Talalay, who gave her stepmother a copy of the comics. Talalay pursued the film rights, which publisher Tom Astor was actively shopping, and in 1995 a movie came out starring Lori Petty and Malcolm McDowell. The movie was a flop but a cult classic with an enduring legacy, not least that several of the Spice Girls met in line for the auditions to play the lead character.

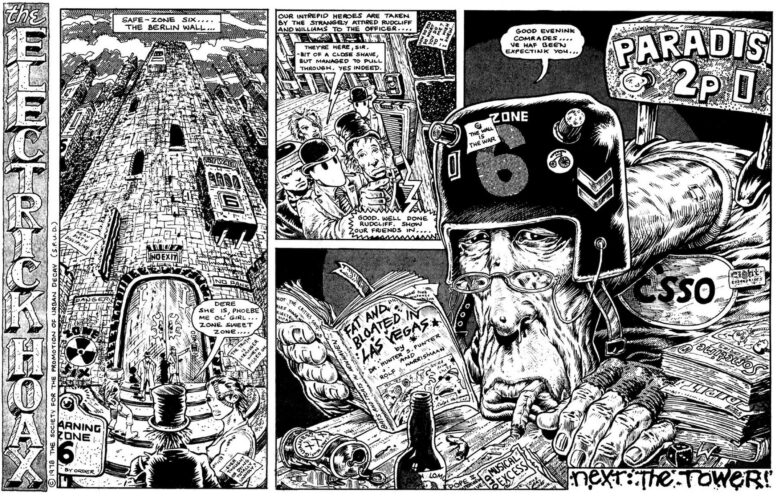

Another significant publication in terms of sitting in the comics/pop culture intersection was Speakeasy, a fanzine that gradually drifted upwards into being a professional publication before it went under in May of 1991. Its last eighteen months, however, featured a monthly one-page column from Grant Morrison called Drivel. As described by Morrison, Drivel was “a monthly, scurrilous, humour, gossip, and opinion column” that they wrote in the voice of “an exaggerated caricature partly inspired by the Morrissey interviews I enjoyed reading. The whole point of the column – which was one of the magazine’s most popular features, incidentally – was to take the piss out of the comics scene at the time.” It’s not entirely clear what Morrissey interviews Morrison is talking about and whether they included his interview two years prior to Morrison’s first Drivel column in which he proclaimed that “Reggae, for example, is to me the most racist music in the entire world” and alleged a black conspiracy to keep the Smiths out of the charts, but the point is clear enough: Morrison was engaging in an exaggeratedly catty and inflammatory performance.

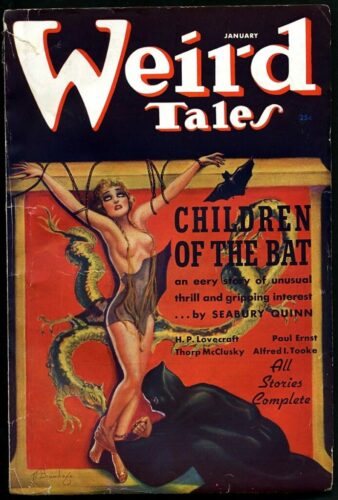

In practice this meant talking shit about other people in the industry—in their first column, for instance, they tartly bashed Howard Chaykin for his claim that “just because he wrote about and drew deviant sexual acts, it didn’t mean that he actually indulged in them. (Deviant? Forgive me if I snore more loudly than usual.)” Later on they take aim at Gary Groth for his Eros line, describing “the entire tawdry exercise” as “a cheap and none-too-cheerful money-grubbing scheme, which is rendered, doubly, triply, and even quadruply odious by the fact that it’s been initiated by one of the most self-righteous, holier-than-thou editorial voices in comics.” Their most infamous moment, however, came in a column in which they first launched their previously discussed suggestion that Moore substantially ripped off Robert Mayer’s Superfolks in various works.…