America a Prophecy 1: Exegesis

America a Prophecy is a new ongoing blog series on Eruditorum Press. It will post annually.

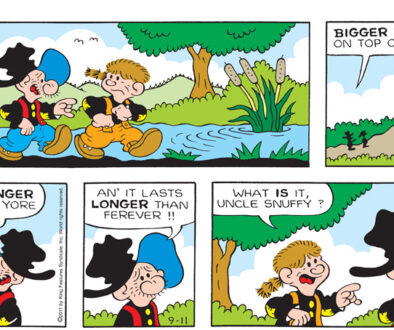

On September 11th, 2011, ten years after the events generally known as 9/11, one of the most extraordinary uses of the comics medium ever appeared in the newspaper strip Barney Google and Snuffy Smith.

As a practitioner of a magical/critical practice that I have coined psychochronography, it is my belief that one can position any cultural object at the center of one’s vision and, through sufficiently thorough exploration of it, understand the larger world in which it exists. To this end, I propose that we explore this genuinely astonishing work of comics art in order to understand the whole of America in the 21st century.

Let us begin with a rigorously tight perspective, understanding the comic strictly on its own formal terms. First of all, the plot: Snuffy Smith has taken his nephew Jughaid on a walk. There is a clear sense of motion in this: the Smiths are in different locations in every panel. At a minimum, they walk the length of Ol’ Man Dowdy’s Pond, reach the base of Mount Tippy-Top (which may well lie more or less immediately at the end of the pond), and then return along the opposite bank of the pond. This theory, which we might call the Short Walk Hypothesis hinges on the idea that the tree in the final panel is the same one as the first panel, only displayed from the other side. This is supported by the fact that both trees constitute a trunk splitting into two branches, one larger and one smaller, and that the smaller one is on opposite sides of the tree in each panel.

This hypothesis, however, requires placing a potentially undue amount of faith in the belief that John R. Rose can draw a significant enough variety of trees to make this visual comparison worthwhile. Beyond the tree, the visuals do not in fact quite line up: the shrubbery between the Smiths and the tree in the final panel does not appear to exist on the far bank of the first panel, while the shrubbery that is visible in the first panel is not visible in the last. This would seem to point towards what we might call the Long Walk Hypothesis, in which the Smiths’ journey constitutes a more extensive traversal of Hootin’ Holler akin to the famous carriage tour of London in chapter four Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s From Hell, in which William Gull, the figure Moore chooses to pin the Jack the Ripper murders on, directs a coach tour of London in which he explains a mystical history of London in a manner familiar to practitioners of psychogeography. Similarly, Snuffy’s account of his grief constituting an extended allegorical narrative related as he and Jughaid visit various physically disparate landmarks.

The Long Walk Hypothesis raises significant questions about the passage of time, however. Snuffy’s lecture simply does not seem to be long enough to play out over an entire day, hence the temptation towards the Short Walk Hypothesis. Equally, the Short Walk Hypothesis strains spatial credulity. Ultimately, neither time nor space need be taken too seriously in the hyperstylized context of the newspaper strip. The curious pacing of the Smiths’ day is not, ultimately, a significant additional weirdness in the face of a comic strip where Snuffy Smith has not visibly aged since his debut in 1934, nor is the seemingly eccentric geography of Hootin’ Holler that odd given that it is a world where feet and legs are basically the same size. Even the broadly realist From Hell takes these sorts of liberties—Moore famously hired a car to verify the plausibility of doing his tour of London in a single day, which is a strange thing to check given that William Gull’s lecture on the mythic history of phallic architecture in no way takes an entire day to read out loud. The relationship between time and geography in comics is never entirely literal.

Nevertheless, the Long Walk/Short Walk question is deeply significant to how one reads the comic. The key problem comes with Mount Tippy-Top. Precisely how big is the giant rock? The visual scale of the panel suggests that while it is certainly a sizeable boulder, the rock that provides scale for Snuffy’s cardiac hole is not actually all that big. Moreover, if one embraces the Short Walk Hypothesis, the entirety of Mount Tippy-Top ends up being pretty paltry. If panel two is depicting the Smiths standing at the base of Mount Tippy-Top, the entire mountain is only about five or six times as big as a human being (however big that is in this world). To use a not especially giant rock on top of what is fundamentally an extremely small mountain as the basis for comparison fundamentally undermines Snuffy’s grief. In contrast, the Long Walk Hypothesis enables the second panel to be read as an outcropping reached after the Smiths have climbed the largely unseen Mount Tippy-Top, which would allow for a reading in which Snuffy’s grief is comparatively sincere.

The textual evidence of the strip at large mostly supports the consequences of the Short Walk Hypothesis and its attendant implication that the hole in Snuffy’s heart is not actually all that substantial. Consider, for instance, Ol’ Man Dowdy’s pond, which is seen to have cattails growing roughly in the center of it. The common cattail seen in North Carolina, Typha latifolia, can only grow in relatively shallow water, maxing out the depth of Snuffy Smith’s grief at roughly thirty inches. Similarly, the panel in which Snuffy proclaims that “it lasts longer than forever” is, ironically, the smallest panel in the strip, which, within the grammar of comic strips, means that this moment is brief and swiftly moved past. Even Jughaid’s facial expression, which is locked in a rictus of pained unhappiness well before Snuffy reveals the subject of his oration, suggesting a sadness that comes not from remembering a national tragedy but from the fact that he is being forced to witness this fundamentally absurd performance. In other words, the strip repeatedly makes an active effort to suggest that the hole in Snuffy’s heart left by the victims of 9/11 is not, in fact, all that big.

The question of whether this is intentional will be left for further installments of this series; suffice it to say that a strictly formalist reading of the strip suggests a high degree of irony in the conclusion. Indeed, perhaps the most significant point to raise about the comic is simply that it is, in practice, still structured like a joke. The strip spends its first four panels actively avoiding saying or doing anything that would tip its hand about 9/11. That information is held back until the final panel, where it serves as a surprise that recontextualizes everything that has come before. This is a comedy structure—one that newspaper strips use routinely. Indeed, the first four panels are configured to take advantage of the normative context of newspaper strips. They are supposed to read as the setup to a joke, this being what a newspaper strip usually is. We, as readers, are supposed to read along with Snuffy’s descriptions, wondering what “it” is, and with the expectation that the answer will humorously undercut or subvert the setup.

This structure does not inherently preclude a sincere or substantive engagement with 9/11–it’s entirely normal for comedy to use its final reveal for brutal effect—a stunned, awkward laugh that makes use of the shock of a perspective shift. But that’s not what’s going on here. The revelation that Snuffy has been talking about 9/11 does not provide any incisive commentary on what has gone before—it is simply a sudden intrusion of grief into a context that had done little to suggest such a thing was coming.

Is this supposed to be funny? Certainly it in practice is funny, in that the strip is a ridiculous absurd thing. But this is a humor of bathos—one in which we laugh at the strip instead of with it. Indeed, it is funny only to the precise degree that it isn’t supposed to be. If the strip is read as insincere, with its punchline meant to be funny then it becomes a cruel and ghoulish thing. What is funny about it is its misapplied sincerity—the fact that it genuinely appears to be engaging in an act of public mourning and is getting it wrong, instead ending up weirdly and dissonantly tone deaf.

And yet as noted, the actual details of the strip when read closely, appear to strongly support an insincere reading. Although it’s worth being precise about where the insincerity is. One need not, after all, assume that Snuffy Smith is being insincere. Indeed, this reading is poorly supported by the strip, where his downturned expression and look of sorrow strongly suggests that he, at least intends this to be a sincere meditation on grief. If the strip is at all deliberate in its efforts to undermine that, this forms a critique of vapid displays of public mourning. Snuffy believes that he is engaged in some sort of profound and moving statement about his grief over a national tragedy, but he subconsciously reveals the vapidity of his performance by framing his grief in such trivial and underwhelming terms. It will not escape your attention, of course, that the alternative reading of the strip is basically the exact same thing, only it’s John R. Rose who’s engaged in the misjudged performance of grief instead of his character.

In practice the strip exists in a strange and irresolvable tension between these two readings. On a fundamental level, no matter how much textual evidence one musters for the idea that it is Snuffy, not Rose, whose bathos we are laughing at, something about the basic fabric of the strip resists this. There is an inexorable gravity pulling towards the interpretation that this is a deeply incompetent piece of graphic storytelling.

It is here that it becomes necessary to turn to the context in which this installment of Barney Google and Snuffy Smith appeared: a tenth anniversary commemoration of 9/11 entitled Cartoonists Remember 9/11. In this, a total of ninety-five ongoing newspaper strips set aside their Sunday strip to respond to the memory of 9/11 ten years on. What this meant in practice was that Sunday comics sections were filled wall to wall with mawkish and poorly designed 9/11 strips, of which Barney Google and Snuffy Smith was merely one. As few if any newspapers lead their Sunday sections with Barney Google and Snuffy Smith, this meant that by the time a given reader reached the strip they were already well-accustomed to the conceit of the section. True, not every comic joined the effort—perhaps most notably, Jim Davis’s Garfield, which remains one of the most common strips to appear on the front page of comics sections, did not participate, instead running a strip in which everyone in Garfield’s house sweats profusely because Garfield is clinging to the front of the air conditioner hogging all the cool air.

Most comics, however, took a format along these lines:

The most common basic structure was demonstrated by Blondie: a single tableau of the comic’s characters commemorating the anniversary.

And many were indeed every bit as farcially mawkish as Barney Google and Snuffy Smith.

Variations on the approach, however, abounded. One common one, demonstrated by Nancy, was more of an illustrated essay on the topic—B.C. provides another example.

Another reasonably common approach focused on commemorating first responders.

That approach, meanwhile, could blur into another, in which the occasion was used to espouse various forms of softly right-wing politics.

Less common, but certainly not entirely absent, were comments on the practical legacy of 9/11. This most frequently took the form of grousing about increased airport security.

Although Bill Griffiths’s famously vexing Zippy the Pinhead took a more oblique approach, and was the only strip to grapple with the subsequent War on Terror.

A less common still approach came with the handful of strips that still attempted to engage in straightforward comedy. This was normally simply strange:

But on occasion it could result in strips of actual warmth and humor, such as this example from Bill Holbrook, which poked gentle fun at the overall spectacle of public mourning.

Within these, Barney Google and Snuffy Smith still stands out, both for its structure and for the unusual degree of its bathos. Its underlying structure—pretending that it’s going to be an ordinary comedy strip before veering into raw sentimentality—was extremely uncommon, with the comparatively obscure Todd the Dinosaur serving as the only other example.

This structure, in the context of the larger comics page, creates an interesting tension when reading the strip—the reader is aware that the comic will more likely than not resolve into something 9/11 related. And yet the possibility that it won’t exists—between non-participants like Garfield and the puzzling phenomenon of strips that ran entirely normal installments with quick extra panels about 9/11 tacked onto the end.

This means that Barney Google and Snuffy Smith in practice read with a strange sort of suspense—a reader of the Sunday section in 2011 would proceed through the strip wondering the whole time whether it was going to resolve into being another tone deaf 9/11 strip or not. The dramatic arc of the strip becomes four panels of going “no, they’re not actually going to do this, are they? No” followed by a punchline of “oh god they did.”

But in many ways this surrounding context only widens the scope of the question. Barney Google and Snuffy Smith is, to be sure, a contender for the most bafflingly surreal of the set, but it is merely the exemplar of what is, on the whole, an extremely weird and awkward set of comic strips. It is not going to be possible to fully unpick what is going on in Barney Google and Snuffy Smith without unpacking the larger context of ninety-five cartoonists doing kitschy 9/11 strips in the Sunday section.

Next Time: The Devolution of the Funny Pages From 1895-2022.

September 13, 2021 @ 12:31 pm

First! To comment on what would appear to be your most temporally audacious project yet.

Now I’m dreading ever finding out what Family Circus put out for the date.

October 28, 2023 @ 7:31 pm

Oh, no, you see, the mountain is actually very large. It is simply extending far, far into the distance, like a hugely lengthened Pride Rock. Which of course means that the boulder at its tip is the largest boulder in the world by far, and appears poised to either tip off the top of Mount tippy-top and impact the earth with a thud registered on the Richter scale, OR, going the other way, it could very easily roll down the mountain straight towards Hootin’ Holler. Snuffy has bigger things to worry about than some pissant terrorist attack from decades ago.

November 5, 2024 @ 4:54 pm

Finally got around to reading this. May I just say, I salute your critical skills. This was very interesting.