The Proverbs of Hell 10/39: Buffet Froid

BUFFET FROID: Literally “cold buffet,” referring specifically to a charcuterie platter of thin-sliced meats. In this context, a joke about Georgia Madden’s shredding skin.

BUFFET FROID: Literally “cold buffet,” referring specifically to a charcuterie platter of thin-sliced meats. In this context, a joke about Georgia Madden’s shredding skin.

It goes without saying that there is a strange unreality here, but this is presented very differently from how Hannibal usually proceeds. It’s never before had to conjure a disposable POV character just to kill her off a few minutes later. Part of this is the peculiarities of Georgia Madden – she’s unsuitable to be a POV character herself, and there’s only one other choice. But a more basic reason is that this is the opening of a horror movie, with Madden being positioned as something that comes at the show from an odd angle She doesn’t quite belong in this series. Unlike with “Œuf,” a previous case of a killer of the week who’s not quite right for Hannibal, this is something the show is at least conscious of this time.

Timeline of events.

- May 2013: “Buffet Froid” airs.

- July 2013: Steven Moffat casts Lars Mikkelsen, brother of Mads Mikkelsen, in “His Last Vow”

- February 2014: Moffat writes “Listen,” featuring a monster that grabs your ankle from under the bed.

I leave you to your own conclusions.

HANNIBAL: We both know the unreality of taking a life, of people who die when we have no other choice. We know in those moments they’re not flesh, but light and air and color.

WILL GRAHAM: Isn’t that what it is to be alive.

Hannibal’s line here is a characteristically interesting blend of deceit and honesty. His account of people becoming “light and air and color” is quite untethered to the handful of instances of actual necessity in which Hannibal has killed someone, and for that matter an unusual description for Hannibal, whose victims are pointedly never “not flesh.” Some explanation is offered by the source, which is unsurprisingly the Thomas Harris novels, where a similar account is given by Francis Dolarhyde, who describes killing this way while projecting this assessment onto Hannibal. Its repurposing into a half life with which Hannibal ensnares Will into mutual aesthetic appreciation is clever.

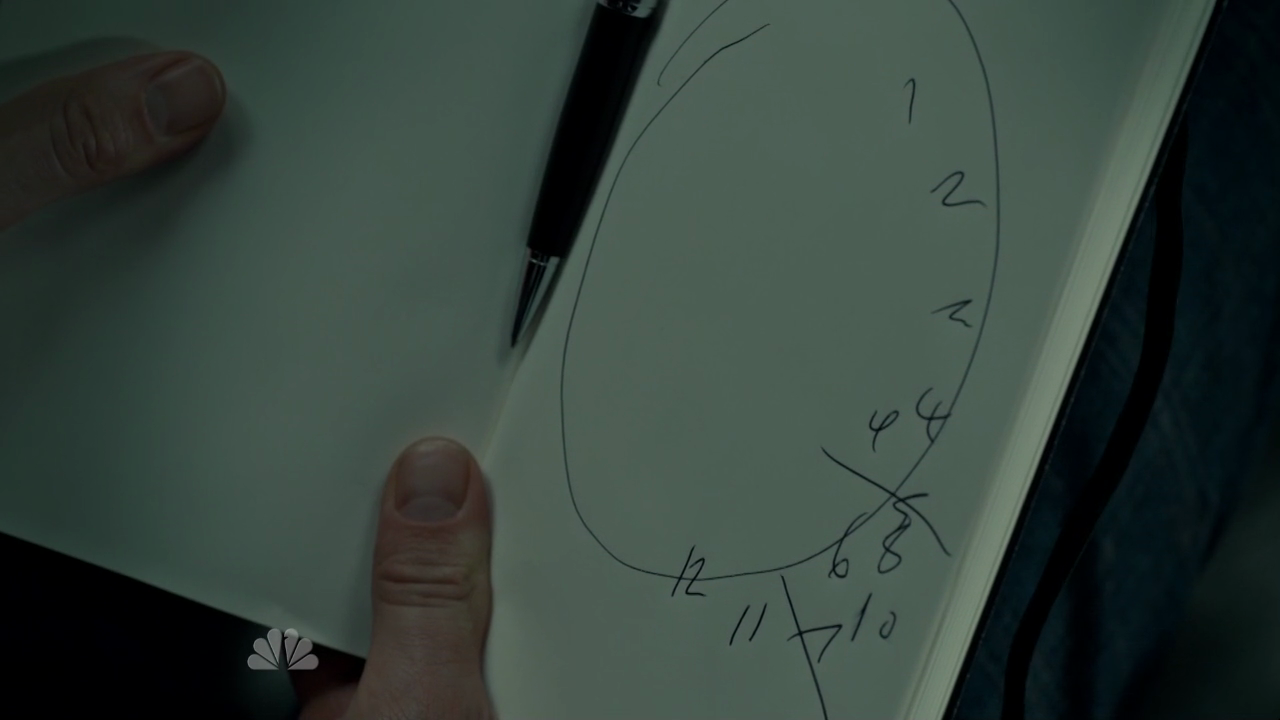

The misdrawn clocks are one of the defining images of the latter part of the first season – an immediately arresting image that communicates wrongness and sinister intent without actually having anything overtly horrifying about them. In this regard they are much like the trypophobic food designs, the cluster of numbers and vast expanse of white space both communicating a sense that this is not right even beyond the contextual horror of Hannibal’s manipulations, which are suddenly revealed to be far more advanced than the audience had realized. Note, of course, the consistent feature of Will’s breakdown: the decoherence of time.

…JACK CRAWFORD: You contaminated the crime scene.

WILL GRAHAM: I thought I was responsible for it.

JACK CRAWFORD: You thought you killed that woman?

WILL GRAHAM: Sometimes with what I do —

JACK CRAWFORD: What you do is take whatever evidence there is and extrapolate. You reconstruct the thinking of a killer, not think you are a killer.

TROU NORMAND: A palate cleansing drink of apple brandy, sometimes with a small amount of sorbet. Your guess is as good as mine, frankly.

TROU NORMAND: A palate cleansing drink of apple brandy, sometimes with a small amount of sorbet. Your guess is as good as mine, frankly.

FROMAGE: Cheese. Relating this directly to the episode contents is tricky – it’s most likely a reference to Franklyn’s declaration last episode that he and Hannibal are “cheese-folk,” although it’s certainly possible Fuller imagined this episode to be somehow cheesier than previous ones. I mean, it does involve opening people up and playing them like cellos.

FROMAGE: Cheese. Relating this directly to the episode contents is tricky – it’s most likely a reference to Franklyn’s declaration last episode that he and Hannibal are “cheese-folk,” although it’s certainly possible Fuller imagined this episode to be somehow cheesier than previous ones. I mean, it does involve opening people up and playing them like cellos.

SORBET: A frozen dessert made of sweetened, flavored water. In this case, it seems meant to suggest a palate cleanser, resetting the meal after the extremes of “Entrée.”

SORBET: A frozen dessert made of sweetened, flavored water. In this case, it seems meant to suggest a palate cleanser, resetting the meal after the extremes of “Entrée.”