Build High For Happiness 1: High Rise (2015)

a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiences

a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiences

High-Rise is an arch film, its thematic building blocks routinely presented explicitly in dialogue. In an early and particularly gleeful instance Tom Hiddleston lectures, “as you can see, the facial mask simply slips off the skull” while literally stripping the flesh off a cadaver’s skull, a statement of theme and demonstration of method all in one. This is, of course, a Ballard thing; the assimilation of his characteristically declarative style into a cinematic language for which it is not an entirely natural fit.

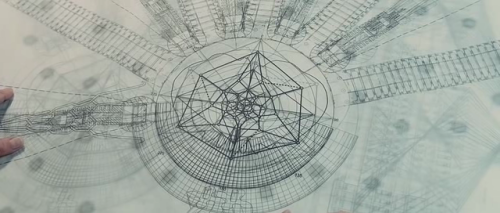

A second example, from when Hiddleston’s character, Robert Laing, is first meeting the High-Rise’s architect Anthony Royal (a name contrasting with the similarly symbolic Richard Wilder, the film’s primary working class character): looking at a blueprint of the building, he proclaims, “it looks like the unconscious diagram of some kind of psychic event.” It’s as Ballardian a sentiment as has ever been expressed, and indeed a more or less direct quote from the novel. As with the casual declaration of the thin line between society and barbarism, this is a statement of both theme and method – in this case a restatement of the basic and underlying premise of psychogeography, namely that exterior landscape shapes internal experience. In High-Rise this is framed primarily in terms of architecture, and specifically in a critique of brutalist modernism and its utopian project. The principle applies more broadly, of course, but all in good time.

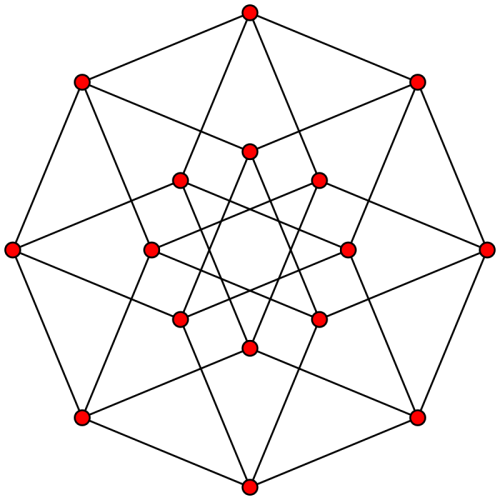

This is, of course, a temporally bounded concern, restricted to the mid-seventies milieu in which Ballard wrote the original novel. As director Ben Wheatley puts it, “if you’re trying to develop a film of High-Rise in 1978, it makes sense to set it further in the future, because the book is probably set in ’82 or ’83. But then that thinking goes on and on, and eventually you get too far away from the book, and more importantly from the technology. You get into the world of social media, and then the story about the isolation of the tower doesn’t work any more.” The fact that the high-rise is a spatial prison is made explicit in the film in a sequence where Laing attempts to leave the building to go to work only to be seized by agoraphobia and sent rushing back, but it is essential to realize that in fact the building’s residents are imprisoned in both space and time – the circumstances in which their slide to barbarism takes place tightly constrained to the London Docklands, 1975. It is, in other words, not merely a tower block but a tower hyper-block, which is, in point of fact, what Royal’s blueprint most obviously resembles.

|

|

The ironic effect of demarcating a fourth dimension of this prison is to increase the number of adjoining spaces, just as extending a square into the third dimension increases the number of walls. This question of neighboring spaces is explicit in the film’s closing moments, as Laing, finishing up the dog, looks over at the second high-rise in the complex, awaiting its descent, “ready to welcome its residents into this new world with open arms.”…

A guest post by Noah Berlatsky, from his new book

A guest post by Noah Berlatsky, from his new book  Moore, drawing from Bunyan, calls it Mansoul. Blake goes with Eternity, while the Aboriginal Australians call it the Dreamtime. Kabbalistically it’s Yesod. It is the world in which the implications of things are made real, their secret histories and imagined futures stretching into the horizon, ghosts and possibilities not haunting them so much as simply inhabiting them, the ordinary and everyday population of the vast and surreal psychic metropolis. When your children asked you where Mario goes when he’s out of lives, this is what you were afraid to tell them.

Moore, drawing from Bunyan, calls it Mansoul. Blake goes with Eternity, while the Aboriginal Australians call it the Dreamtime. Kabbalistically it’s Yesod. It is the world in which the implications of things are made real, their secret histories and imagined futures stretching into the horizon, ghosts and possibilities not haunting them so much as simply inhabiting them, the ordinary and everyday population of the vast and surreal psychic metropolis. When your children asked you where Mario goes when he’s out of lives, this is what you were afraid to tell them.  No comics reviews this week. I just can’t. We’ll see about next week when we get there, but I was thinking of winding down the feature anyway, so peg your expectations accordingly. Instead, here’s this week’s Super Nintendo Project.

No comics reviews this week. I just can’t. We’ll see about next week when we get there, but I was thinking of winding down the feature anyway, so peg your expectations accordingly. Instead, here’s this week’s Super Nintendo Project. One final guest post from Anna Wiggins. Also,

One final guest post from Anna Wiggins. Also,