Build High For Happiness 1: High Rise (2015)

a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiences

a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiences

High-Rise is an arch film, its thematic building blocks routinely presented explicitly in dialogue. In an early and particularly gleeful instance Tom Hiddleston lectures, “as you can see, the facial mask simply slips off the skull” while literally stripping the flesh off a cadaver’s skull, a statement of theme and demonstration of method all in one. This is, of course, a Ballard thing; the assimilation of his characteristically declarative style into a cinematic language for which it is not an entirely natural fit.

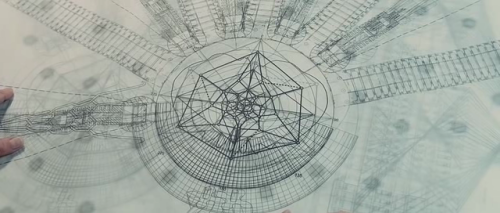

A second example, from when Hiddleston’s character, Robert Laing, is first meeting the High-Rise’s architect Anthony Royal (a name contrasting with the similarly symbolic Richard Wilder, the film’s primary working class character): looking at a blueprint of the building, he proclaims, “it looks like the unconscious diagram of some kind of psychic event.” It’s as Ballardian a sentiment as has ever been expressed, and indeed a more or less direct quote from the novel. As with the casual declaration of the thin line between society and barbarism, this is a statement of both theme and method – in this case a restatement of the basic and underlying premise of psychogeography, namely that exterior landscape shapes internal experience. In High-Rise this is framed primarily in terms of architecture, and specifically in a critique of brutalist modernism and its utopian project. The principle applies more broadly, of course, but all in good time.

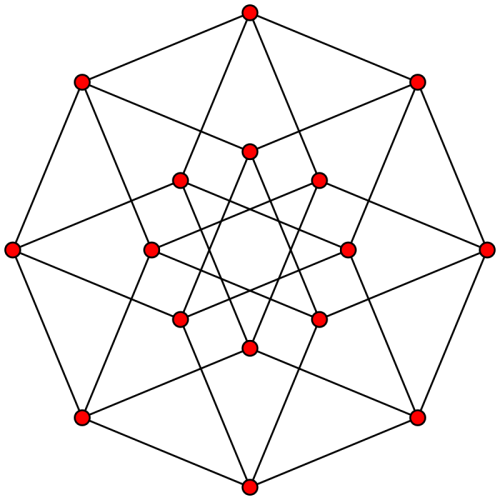

This is, of course, a temporally bounded concern, restricted to the mid-seventies milieu in which Ballard wrote the original novel. As director Ben Wheatley puts it, “if you’re trying to develop a film of High-Rise in 1978, it makes sense to set it further in the future, because the book is probably set in ’82 or ’83. But then that thinking goes on and on, and eventually you get too far away from the book, and more importantly from the technology. You get into the world of social media, and then the story about the isolation of the tower doesn’t work any more.” The fact that the high-rise is a spatial prison is made explicit in the film in a sequence where Laing attempts to leave the building to go to work only to be seized by agoraphobia and sent rushing back, but it is essential to realize that in fact the building’s residents are imprisoned in both space and time – the circumstances in which their slide to barbarism takes place tightly constrained to the London Docklands, 1975. It is, in other words, not merely a tower block but a tower hyper-block, which is, in point of fact, what Royal’s blueprint most obviously resembles.

|

|

The ironic effect of demarcating a fourth dimension of this prison is to increase the number of adjoining spaces, just as extending a square into the third dimension increases the number of walls. This question of neighboring spaces is explicit in the film’s closing moments, as Laing, finishing up the dog, looks over at the second high-rise in the complex, awaiting its descent, “ready to welcome its residents into this new world with open arms.” Another neighbor is offered moments later, in the film’s final image of the young Toby, illegitimate child of Anthony Royal, sitting in a throne-like chair adorned with antennas, listening to a speech by Margaret Thatcher. But there are numerous other adjacent psychic spaces: the iconic “Kids Rule OK” cover of Action, the film Morgan – A Suitable Case for Treatment, Freud’s The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, and of course ABBA’s “SOS,” released the same year as Ballard’s book and used twice in the film, once in a baroque orchestral number over a mock-Versailles party early in the film, once in a glowering Portishead cover that pulses like a rotten heart in a bloodsoaked third reel montage.

The video for “SOS” incorporates numerous video effects so that the band are distended through funhouse reflections or, most notably, whirled in kaleidoscopic blurs. Wheatley and his screenwriting/editing partner Amy Jump incorporate their own reflection of this figure in the film when they give outcast child Toby a kaleidoscope through which he peers at various points in the film, most notably to observe Wilder’s death at the hands of the now-unified women of the high-rise at the film’s end. And it is the occasion for one of the film’s defining on-the-nose bits of meta-text, as Laing asks him what he can see through it and Toby replies, with deadpan nonchalance, “the future.” And of course he can: the kaleidoscope is just another iteration of the hypercube.

|

|

Toby’s claim mirrors the line of dialogue used at the start of the Portishead montage (and on movie posters) as BBC announcer Cosgrove peers out from within a discarded television to ask his neighbors, “what are you doing in there?” This marks a striking level of metatextual density even for High-Rise inasmuch as it literalizes the question of televisually representing the social order of the high-rise, particularly inasmuch as Cosgrove exists as an upper-floor mirror of Wilder. But for now let’s focus on how Wheatley and Jump approach the problem as opposed to how their characters do, not least because that’s more a concern of Ballard’s novel than their film.

Broadly speaking, the answer is montage – Wheatley and Jump are reliably inclined towards cutting among multiple aspects of the high-rise, establishing their themes and focuses by intercutting between events in various areas of the building. The Portishead montage, for instance, begins with the drums overlaying the final few frames of Charlotte being dragged away to her rape by Wilder, then alternates between Laing lying silently in his apartment and a garbage-strewn hallway with the lone television out of which Cosgrove peers, with his voice appearing over both shots. Midway through the first chorus the image cuts to black from the television (with accompanying sound effect) before coming back with a shot of the high-rise against the sky, cutting to the tower’s women sneaking into Royal’s apartment to rescue Helen, then to Cosgrove departing the complex. The second verse plays out over a single scene of a battered and bruised Charlotte serving Wilder dog food out on the balcony, with the song’s outro playing over Laing receiving an envelope slipped under his door. Some of these cuts are organized according to a narrative logic – Charlotte, for instance, watches Cosgrove walk to his car from the balcony, and ends her scene by looking down at Laing’s balcony prior to the cut to his door – but for the most part the relationships among the scenes is left to implication. And there are many similar sequences: Munrow’s suicide is cut amidst shots of Wilder dancing raucously at a party; Wilder drowning the dog is interspersed with shots of the tower at sunset, lights flickering, and of Laing walking Toby up to his mother’s flat; and Laing having sex with Helen comes in a montage between people dancing ridiculously at a party in Royal’s penthouse and Royal inspecting the cracked glass in his private elevator.

As a cinematic technique, montage is inextricable from Marxism, having been first theorized by Russian filmmakers such as Sergei Eisenstein and Lev Kukeshov. For our purposes what is most interesting here, however, is the degree to which Eisenstein conceptualizes montage in terms of the linearity of film. This contrasts intriguingly with the other dominant theory of editing in early cinema, continuity editing, which, fittingly, was pioneered by the racist authoritarian D.W. Griffith, creating a tidy political dualism between film’s two conceptions of time. In continuity editing the linearity of film is treated as a mandate for order – the sequence of frames that make up a moving images is made to simulate the experience of linear human perception. Montage, on the other hand, treats film’s linearity as a way to transgress against space and time through juxtaposition, using editing to create dialectical progressions. This is immediately adjacent to the dérive, in which the linear progression of a walk is used to transgress against urban spaces to uncover the secret psychogeographies beneath.

But the hypercubic prison imagined by High-Rise poses a new category of problem for the basic montage/dérive technique by incorporating nonlinear time into its design. Its expanded conception of space means that the dérive is anticipated and defended against, all of its paths already worked into the design and thus robbed of the ability to transgress. Its hand (this being what Royal compares the design of the five towers to, with his office “the distal phalanx of the index finger”) is further strengthened by the inherent directionality of the fourth dimension in human experience such that any bounded space within it has an inextricable gravity, serving as a funnel whereby all journeys through the space are drawn inevitably towards its temporal endpoint to be excreted out into the future.

High-Rise is quite clear on the fact that this endpoint is Margaret Thatcher. Wheatley describes the final scene thusly: “the voice of Thatcher is almost like this monster stalking the land and coming for them, but they don’t realise what it means yet. Toby doesn’t know what will happen, but we do. Thatcher exists around the high-rise like an airborne virus. Toby has lost his parents, and then he finds this new, political parent – Thatcher’s voice on the airwaves – through his homemade transistor device. It’s beaming right into his head.” The directionality is inverted, but this is clearly the same metaphor – an inevitable progression from the high-rise to the future. It is particularly telling that Toby is the invention of Wheatley and Jump as opposed to Ballard, and that Wheatley has also spoken of how he and Jump were children of the 1970s, so the slight reinterpretation necessary to transform Toby “finding” Thatcher to Toby being delivered to her.

Clarity, of course, is not the same as honesty. The use of Thatcher as an endpoint to the story serves not only to (in many ways clumsily) focus Ballard’s prophetic tendencies on a single historical object, but also serves to reinforce the fact that High-Rise is staged as a period piece, with Thatcher serving as a metonym for a larger socio-political structure pointing inexorably towards the present day of 2015-16 in which the film was released, extending the bloody birth canal down which Toby is reborn so that it reaches from modernism to the present day, and thus more generally serves as a metaphor for the twentieth century’s delivery of the twenty-first.

This, then, is our prison – this grim conveyor belt dragging the whole of history, the entire cultural edifice against which we define ourselves, towards its waste incinerator endpoint. A hypercube with one cell marked “modernism” and the opposite one marked “death.” Now to plot our escape.

November 26, 2016 @ 3:04 am

This, then, is our prison – this grim conveyor belt dragging the whole of history, the entire cultural edifice against which we define ourselves, towards its waste incinerator endpoint.

“The tenants arrive in the entrance hall here, and are carried along the corridor on a conveyor belt in extreme comfort and past murals depicting Mediterranean scenes, towards the rotating knives. The last twenty feet of the corridor are heavily soundproofed.”

November 26, 2016 @ 8:41 am

Wow! One of your best. The Docklands of course also provided the setting for two cult bookends of 1970s British cinema – A Clockwork Orange and The Long Good Friday. The former, stylishly detourning the reactionary Burgess novel into a blueprint for the seventies. Both Bowie/Glam kids and football hooligans adopted elements of the droog look, amongst other things shifting the bowler hat from symbol of bureaucratic class power to hipster style statement. The latter film of course eerily predicted Thatcherism without the benefit of Wheatly’s hindsight. Contrasting the demolition of a working class area of London, its gentrification and, yes, high rise architecture, with the east end gangster versus IRA terrorism main plot.

November 26, 2016 @ 5:58 pm

Excellent.

Piggybacking, but I reviewed High-Rise (the film) here: https://tommarshallwriter.blogspot.co.uk/2016/03/no-room-to-escape-from-themselves.html

and High-Rise (the book) here: https://tommarshallwriter.blogspot.co.uk/2016/04/on-high-rise-by-j-g-ballard-1975.html

November 27, 2016 @ 5:33 am

Out of curiosity – have you read Cinema 1 by Gilles Deleuze? Your use of Griffith and Eisenstein is strikingly similar to Deleuze’s, although you’re using them to much different ends.

Great post, by the way.

November 27, 2016 @ 2:48 pm

When one asks our host if he’s read something by Deleuze, the answer is probably in the affirmative. Also, I had to tell the pre-filled blanks that I’m not Dylan goodluck.

November 27, 2016 @ 2:58 pm

Yes, though not in enough years that I can honestly say I remember that bit.

(As for the comments bug, yeah, we know – Anna’s having trouble clearing the time to take a crack at re-solving it.)