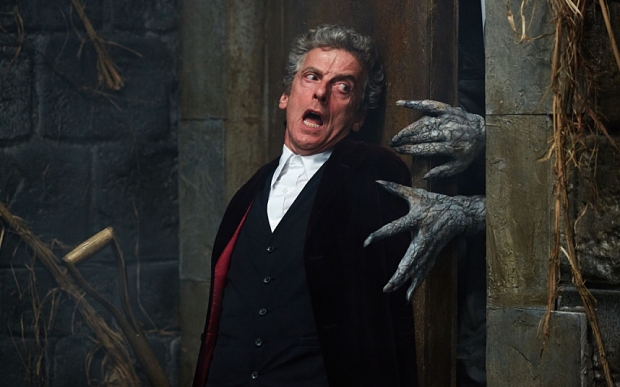

Heaven Sent Review

As I’ve said many a time, what I want out of Doctor Who is something I’ve never seen before. And so I’m not going to argue with anybody who puts this among their masterpieces. If you want to claim it as the equal of Listen or Blink then be my guest. For me, it’s a solid 9/10, and won’t be ahead of The Zygon Inversion in my rankings, so the result is that we’re going to start defensive and then move to the positive.

As I’ve said many a time, what I want out of Doctor Who is something I’ve never seen before. And so I’m not going to argue with anybody who puts this among their masterpieces. If you want to claim it as the equal of Listen or Blink then be my guest. For me, it’s a solid 9/10, and won’t be ahead of The Zygon Inversion in my rankings, so the result is that we’re going to start defensive and then move to the positive.

I suspect the crux of my disagreement with those who will put it higher is simply how much one values the basic idea of the “experimental” in Doctor Who. Which in some ways brings us back to Sleep No More, and in others back to In the Forest of the Night, two episodes that were distinctly experimental and also distinctly flawed. In both cases I value them considerably more than the consensus, and specifically for the odd things they did. And moreover, yes, obviously anyone who’s read any of my work on Doctor Who recognizes that I love its weird tradition, which has always been a huge part of the show, from The Edge of Destruction on. I’m definitely in the general camp of fandom that thinks The Mind Robber, The Deadly Assassin, Warrior’s Gate, and Vengeance on Varos are all cool just for being what they are.

But equally, the “experimental” field is crowded these days. At even the stingiest definition you’ve got to tag Listen, Last Christmas, Sleep No More, and Heaven Sent as experimental episodes in the last two years, and I’d be inclined to widen the net, and count bits of relatively non-experimental episodes like the Beethoven’s Fifth bits of Before the Flood and the two-hander first half of The Woman Who Lived, as well as much of In the Forest of the Night and the direct to camera bits of Kill the Moon. By and large this is why I’m loving the show so much right now. But it causes a small but distinct problem for something like Heaven Sent, which is that the fundamental limitations of how experimental Doctor Who can be really become visible when they’re run up against as often as they are these days. Doctor Who can do brilliantly experimental takes on all sorts of genres: western, Vikings, Restoration comedy, political thriller. But it can’t do an experimental take on experimentalism. That’s just not what it’s for.

This isn’t helped by the fact that the fundamental limitations of how experimental Moffat can be have long since become visible, and for the admirable reason that he keeps punching away at them with glorious stubbornness. This is, somewhat flagrantly, the basic concept of Time of the Doctor done as the show-off sequence in the middle of His Last Vow, with a middle finger emphatically raised at the entire “Moffat fetishizes the Doctor and this is a problem” crowd.

All of which is a very long way of saying that, slightly depressingly, this manages to be a hugely experimental one-hander that doesn’t actually do anything new aside from be a hugely experimental one-hander.…

I’m joined this week by our very own Holy Boson to discuss Face the Raven and whatever else we got off talking about. Apologies for some early audio quality issues with my end; I had a mic problem that straightens out ten minutes or so in.

I’m joined this week by our very own Holy Boson to discuss Face the Raven and whatever else we got off talking about. Apologies for some early audio quality issues with my end; I had a mic problem that straightens out ten minutes or so in.  From my forthcoming colleciton

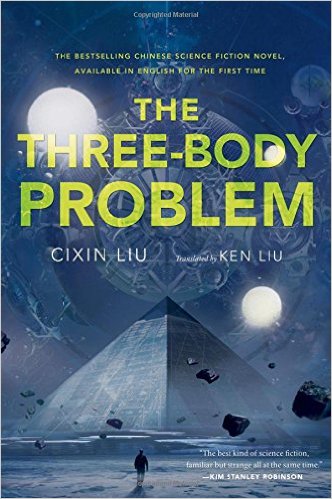

From my forthcoming colleciton

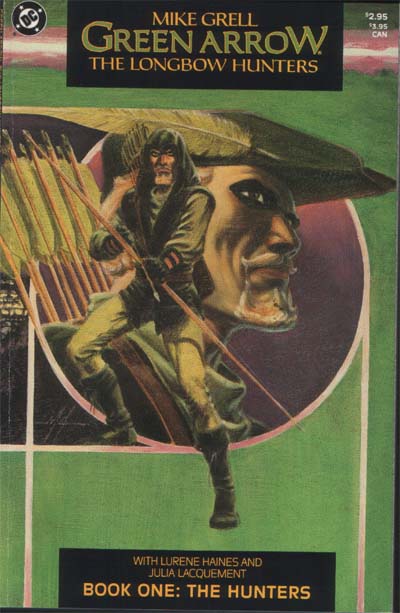

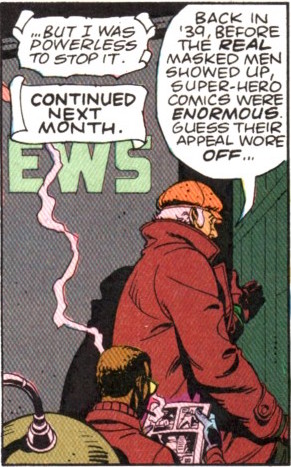

But there is a visible absence in all of this. The Veitch Swamp Thing and Delano Hellblazer runs were excellent books, and will come into focus within the War in good time, but their success in reprints has been a fraction of what Moore’s run has done. The Longbow Hunters sold well and remains in print, but is nothing compared to The Dark Knight Returns, and back issues go for roughly cover price, as opposed to the massive valuation of its predecessor. And as for Watchmen, well, there’s not even an obvious choice to compare it to. In the thirty years since its debut, DC has simply never come close to replicating its success. That they never matched the success of what is arguably the single most successful superhero graphic novel in the history of the genre is, of course, baked into the premise of Watchmen being the most successful, but to have the only other book to challenge it for the title, The Dark Knight Returns, be from the same year is, by any standard, a shocking failure at DC’s primary goal of replicating its own successful formula.…

But there is a visible absence in all of this. The Veitch Swamp Thing and Delano Hellblazer runs were excellent books, and will come into focus within the War in good time, but their success in reprints has been a fraction of what Moore’s run has done. The Longbow Hunters sold well and remains in print, but is nothing compared to The Dark Knight Returns, and back issues go for roughly cover price, as opposed to the massive valuation of its predecessor. And as for Watchmen, well, there’s not even an obvious choice to compare it to. In the thirty years since its debut, DC has simply never come close to replicating its success. That they never matched the success of what is arguably the single most successful superhero graphic novel in the history of the genre is, of course, baked into the premise of Watchmen being the most successful, but to have the only other book to challenge it for the title, The Dark Knight Returns, be from the same year is, by any standard, a shocking failure at DC’s primary goal of replicating its own successful formula.… This week I’m joined by my former partner in crime over at Slate, playwright Mac Rogers, to talk about Sleep No More, Mark Gatiss, and whatever the fuck else we got off topic about. Which, being an Eruditorum Press podcast, was many, many things.

This week I’m joined by my former partner in crime over at Slate, playwright Mac Rogers, to talk about Sleep No More, Mark Gatiss, and whatever the fuck else we got off topic about. Which, being an Eruditorum Press podcast, was many, many things.