Crinkly and Complex (Book Three, Part 72: Numerocracy, Fractals)

Previously in The Last War in Albion: The first issue of Alan Moore and Bill Sienkiewicz’s Big Numbers was a lush and splendid object that positioned itself as a formal heir to Watchmen even as it rejected superheroes in favor of shopping malls and math.

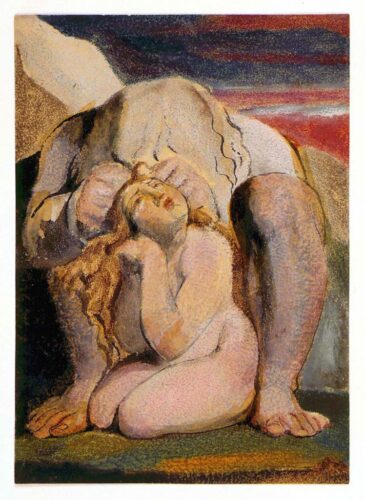

Eventually, the snowflake’s edge becomes so crinkly and complex that its length, theoretically, is infinite. Its area, however, never exceeds the initial circle. Likewise, each new book provides fresh details, finer crenelations of the subject’s edge. Its area, however, can’t extend past the initial circle: Autumn, 1888. Whitechapel. – Alan Moore, From Hell

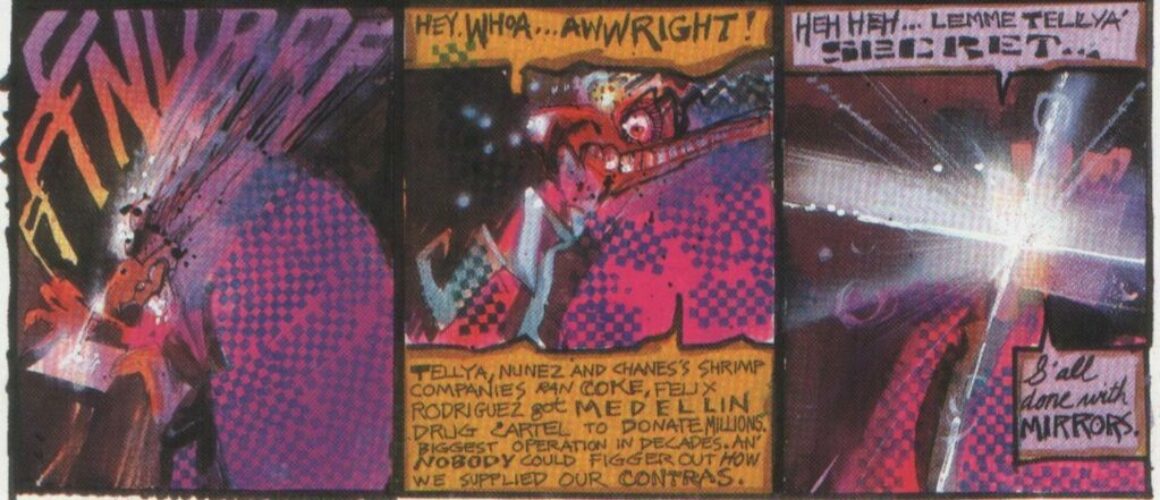

As with Watchmen, Moore uses a detached, omniscient perspective. Indeed, he takes it even further than he did in Watchmen, where he could use Rorschach as a pseudo-narrator. Big Numbers has no equivalent character. The closest it comes to narration is a montage at the end of the first issue in which one of the character’s poems is contrasted with a series of single panels reviewing the various characters that the book has introduced. For the most part, however, Big Numbers is told with an impassive objectivity. It takes flights into individual subjectivities, as with the dream sequence in the opening sequence or a later sequence in which Mr. World, a psychiatric patient released into the “care of the community,” fantasizes about the violent murder of a fellow bus passenger, but even these subjectivities are treated with a level of objectivity, the internal landscapes of the characters being treated as just another thing to look at.

Part of this sense of distance is simply the sheer number of characters involved. Moore’s outline for the series features thirty-one separate characters along with one group of characters, three characters from a story within a story, one ghost, and a set of people in a model railway set that will be treated as characters. In the forty pages of Big Numbers #1, twenty of these are introduced overtly, along with the ghost, and another is positioned in the background of a panel. Even though the action is centered almost entirely on Hampton, it gives the impression of a startlingly broad portrait of the town—one that, by the time the bulk of the remaining characters are introduced in the second issue, spans from the town’s rich and powerful to its underclass, with policemen, construction workers, students, sex workers, shopkeepers, and more all represented within the sweep of its worldview. And by exploring the connections among these people, as works of this sort of sprawling social realist genre inevitably do, Big Numbers displays the same sort of meticulous clockwork precision as its predecessor. The overwhelming sense of the first issue is one of inevitability; that a town in Thatcher’s Britain can only face the arrival of a massive shopping mall in one way. Moore even discussed as much, noting that “What I wanted to do was to show the fragility of human community, human relationships, and then to put this shadow of a large and inhuman shopping mall, a monolith of purely economic concerns, that would cast its shadow over that community.…