America a Prophecy 3: The Only Thing that Stops a Bad Guy with an Emotion is a Good Guy with an Emotion

Scrape away the deconstructive close-reading, scrape away the history of decline, scrape away the entire wilfully absurd edifice of an annual blog series devoted to it and what you are left with is an unusually bathos-heavy bit of glurge.

The word “glurge” was coined by Patricia Chapman on a mailing list attached to the website Snopes. “Glurge” referred to a specific category of urban legend—the heartwarming, inspirational, and completely uncited and often fact-free stories that were often sent via e-mail in the late 90s and early 00s by the sorts of elderly relatives who would soon be preyed upon by the likes of Fox News and Breitbart. The term originally came out of the site’s then focus on urban legends, describing a common style of story characterized by an unabashed and excessive sentimentality. A doctor operates for free on a young girl that once gave him a glass of milk. A dying child comes back from the brink when her brother sings “You Are My Sunshine.” A marine comforts a dying stranger in the hospital. Stuff like that.

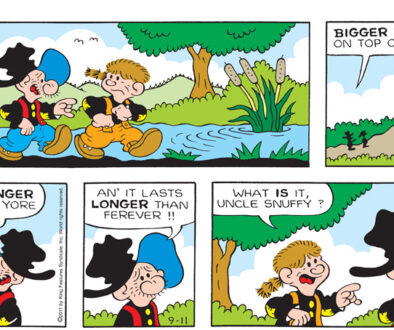

9/11 provided something of a heyday of glurge—a sticky, cloying spray of it so voluminous that it becomes possible to identify distinct subgenres of glurge. There’s state glurge, like a motley collection of Members of Congress singing “God Bless America” on the Capitol steps. There’s imperialist glurge, like Toby Keith’s “Courtesy of the Red, White, and Blue.” There’s first responder fetishism, stories of American resilience, impassioned insistence about the dignity of American Muslim. And then, of course, there’s the category that John Rose’s Barney Google and Snuffy Smith comic fits into: public mourning.

Public mourning is a concept I’ve always had a complicated relationship with. There’s a stagedness to it—a sense of perfunctory ritual in the place of actual emotive content—that runs counter to how I experience grief. Equally, of course, there are people who value it highly. One need only look at the scenes taking place in the UK when the last post went up and the sheer number of people standing in an hours-long line to shuffle past a box to see that these rituals of mourning carry weight. This is an important thing to keep in mind when we look at a misfiring bit of public mourning like the Barney Google and Snuffy Smith strip.

On the other hand, it’s not an especially radical observation to note that public mourning really can go embarrassingly wrong. Perhaps the worst piece of public mourning glurge I ever saw for 9/11 came a few years before I wrote that essay, in the parking lot for my vet’s office in Florida, where a car routinely sat bearing a bumper sticker that read “am I the only one who still mourns 9/11?” Like the Barney Google and Snuffy Smith strip, this bumper sticker provokes a certain awed horror. The question it asks is singularly stupid—the only possible response is “of course you aren’t, you narcissistic twatwaffle.” But this reveals what should be perfectly obvious, which is that the question is rhetorical. The person displaying the bumper sticker is not sincerely asking who else is still mourning 9/11; they’re castigating the world at large for not mourning 9/11 enough.

The sense of outrage implicit in this is characteristic of the form. The point of glurge in general, after all, is the reduction or elimination of ambiguity. Its bathetic over-earnestness exists to construct a reality of simple, aggressively straightforward morality. That this morality focuses on excessive, stagey goodness is largely immaterial—equally cartoonish evil exists, it’s just handled in different propaganda than glurge. The point is simply that there’s no complicated nuance or irony here. (Indeed, those who were old enough for 9/11 to be a feature of their adulthood will remember the endless discussions of the “death of irony” that it supposedly heralded. Irony, thankfully, proved more durable than feared.) Glurge does not simply tell you how to feel, it attempts to cut off all alternatives to that feeling. This explains, among other things, the strange and uncanny alienation that it provokes in those disinclined towards the prescribed emotion.

None of this, however, explains why 9/11 provoked so fucking much of it. This may seem a strange question, given how obvious it was at the time that the correct response to 9/11 was a torrent of sentimental crap—so obvious that even those not especially sympathetic to it largely conceded the point. And yet it’s worth noting that 9/11 saw the death of just shy of three thousand people; the weekend this blog series began saw the death of 3315 in the US alone, part of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which, once the death toll started to rise in earnest, provoked a surprising lack of glurge, and certainly no universal consensus for it. Clearly, in other words, the reason that 9/11 required glurge was not simply that a lot of people died and it was very sad.

The key factor, I would argue, is implicit in what 9/11 provoked: the war on terror. Note that it was always described this way—not as a war on terrorism, or on terrorists, or on Al Qaeda, but a war on the emotion of terror itself. This gets at what the true wound of 9/11 was, which was not simply a moderate death toll but the permanent disfiguring of the New York City skyline, which was itself a metonym for America. This is also crucial to the oft observed dynamic where people in New York City turned out to be far less fond of the war on terror than elsewhere in the country. It wasn’t the damage to New York City itself that mattered; it was the symbolic damage.

Although by any remotely sane moral standards violence against architecture pales before killing thousands of people, violence against fundamental symbols of America is not supposed to happen. The United States of America is an appallingly wealthy country with an absolutely mind-wrenching level of military strength, and the entire point of being one of those is supposed to be that things like this don’t happen. But, of course, the nature of terrorism as an asymmetrical tactic is that instead of attempting to win unobtainable concrete material goals you simply engage in high profile strikes that make your enemy look vulnerable. Instead of attacking a country, you attack its myth. And so the response was focused primarily on the restoration of that myth. In the main, this was accomplished not through shitty comic strips but by bombing the shit out of people until we felt better. But glurge was also a part of the solution. But if the 9/11 attacks were meant to spread fear, the terrifying glut of glurge was meant to spread… what, exactly?

To some extent, there’s not a singular answer to this, or at least not a coherent one. Its goals are, in the end, fundamentally contradictory in the face of the reality that all killing three thousand people and scarring the New York City skyline took was a couple guys with box cutters. Sure, you can erect a deafening security theater around airports to make sure that specific attack doesn’t happen again, but the fact of the matter is that terrorism is easy to commit and impossible to defend against, doubly so when you’ve made ownership of an AR-15 trivial. Which is why the twenty-two years since 9/11 have been full of mass shootings, cars driven into crowds, and more. The fact that it can be done by ordinary people without any particular training is central to terrorism as a tactic. So any actual countering of the existence of that fear is futile.

With actual safety off the table the culture turns instead to a story of American resilience. This was particularly visible at the inevitable benefit concerts—the America: A Tribute to Heroes telethon on September 21st, and the VH1-aired Concert for New York City a month later—where, songs played included David Bowie’s “Heroes,” Maria Carey’s “Hero,” Enrique Inglesias’s “Hero” (conveniently his latest single), Five for Fighting’s “Superman (It’s Not Easy), and Tom Petty’s “I Won’t Back Down” for the theme of direct resilience/heroism, while other popular picks included songs including the word “America” (curiously always covers—Bowie played Simon and Garfunkel’s “America” while the Goo Goo Dolls played Tom Petty’s “American Girl”), Billy Joel’s “New York State of Mind” at both concerts, and a wealth of inspirational schmaltz like Stevie Wonder’s “Love’s in Need of Love Today,” Wyclef Jean covering Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song,” Neil Young playing “Imagine,” and, in perhaps the most intensely 2001 moment it is possible to imagine, the lead singers of the Goo Goo Dolls and Limp Bizkit dueting on a version of Pink Floyd’s “Wish You Were Here” with new lyrics written about 9/11. On aggregate, it feels like an Americanized remix of the “Keep Calm and Carry On” posters—a message that, yes, sure, terrorism is now a constant threat, but it’s fine because of some nebulously defined but supposedly universally felt notion of America.

Of course, this was mostly happening in 2001 and 2002, and while it’s all aged terribly poorly, it at least made a certain emotional sense in the moment. One can make the comparison to COVID to highlight the hypocrisy, but the fact of the matter is that 9/11 had it right: 3000 people dying should be a big deal. Yeah, a lot of the public response felt chintzy at the time, but outside of a few unusually tone deaf exceptions it mostly felt like an appropriate chintz, or at least like an inevitable one. But the Barney Google and Snuffy Smith strip came a decade later, in 2011, when the needs for glurge had changed markedly. Its insistence on a universally shared sense of grief and pain falters against the reality that ten years is largely enough time to mourn, heal, and move on. 9/11 was, in spite of the strip’s po-faced insistence, no longer an active and immediate wound on the American psyche anymore, and this sort of schmaltz felt very different.

And yet the glurge remained. But instead of providing a simple thing that one could latch one’s grief onto in order to foster a sense of national unity and identity in the wake of a terrorist attack, its purposes were somehow even more sinister. By the time of September 2011 the Iraq War was still dragging on, though near its end, or at least near the phase where we began conducting it entirely with drones, while Afghanistan would have another decade to run. Osama bin Laden had finally been killed earlier that year, but the war on terror was rumbling onwards, with no real sign of abating.

I mean, that’s the real reaction to “am I the only one who still mourns 9/11” as a question. Of course not; if you were, we wouldn’t be bombing people. Which is to say that this later glurge serves a subtly altered purpose. Instead of attempting to heal the psychic wound of 9/11, it’s endlessly reiterating and attempting to reinvoke the patriotic unity of a decade ago so as to justify the staggering enterprise of eternal war. Make no mistake, this was the real content of Snuffy Smith’s claims about the hole in his heart: that it was casus belli, that the pile of mutilated corpses left in the wake of our drones were justified. Which is quite a weight to put on a bad comic strip that was already sagging under the weight of its own facile vapidity.

And yet it exists. Mockable as it may be, this comic and dozens of only slightly less stupid ones got made and published. We can deconstruct the ideology and come to have an understanding of exactly what’s going on, but that doesn’t remove or even really ameliorate the vertigo of it. Mapping out the skeptical position is easy, but the question still remains: who is this for?

Answering that question with any specifics is, of course, very difficult, especially a decade later. Finding someone who opened their paper that Sunday, read Barney Google and Snuffy Smith, and thought “oh, wow, that’s great” is not an especially realistic critical technique. So let’s do the next best thing and ask who it is that creates something like this strip.

Next Time: Rose

November 8, 2024 @ 4:51 am

“Glurge”, that’s a nice word. I’ll be adding it to my vocabulary, thanks.

And thanks for the great essay.