America a Prophecy 2: The Devolution of the Funny Pages, 1895-2022

CW: Racist imagery, not discussed by the larger essay

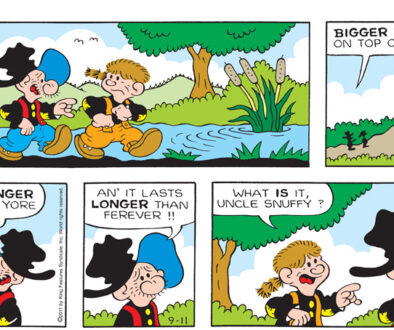

One complicating factor in our exegesis of the 9/11/11 Barney Google and Snuffy Smith strip is that the strip exists in two different forms with two distinctly different resonances. Last year we discussed a five panel version of the strip, however another version exists and saw publication with an additional sixth panel at the beginning of the strip.

At first glance this version of the strip seems to collapse some of our discussions, particularly around whether Snuffy’s final line constitutes a punchline or not. The addition of Snuffy reading a newspaper marking the anniversary of 9/11 and weeping while Jughaid looks in from the window and weeps alongside him removes the element of bathetic surprise that the five panel version of the strip traded on. More to the point, it renders the strip strangely incoherent—if Jughaid has just been weeping at the cover of the newspaper, his confusion as to what the strange perambulatory ritual that Snuffy is engaged in might be about becomes harder to reconcile.

Broadly speaking, and inasmuch as discussions of craft can be applied to the strip, the addition of the new opening panel unquestionably harms the strip, muddying its intentions and rendering it incoherent in places where its coherence had been, if not strictly speaking a positive, at least broadly interesting. But while the panel muddies interpretation of the strip, it is clarifying in a different sense. The key question to ask is simple: why are there two different versions of the 9/11/11 Barney Google and Snuffy Smith strip in the first place?

The answer is tied to the medium of newspaper comics themselves. By 2011 (or indeed decades earlier) newspaper comics sections had become extremely compressed things that attempted to fit as many comics into as small a space as possible. To accommodate this, the syndicates that distribute the comics sought to ensure the comics were rearrangeable. Part of this meant that the initial panels of a Sunday strip had to be disposable—the comic had to work with or without them. An ordinary example can be found in this 1991 Calvin and Hobbes strip, in which the first two panels are a standalone gag that the remaining panels do not depend on.

In fact the rearranging goes far further, however. Note in the Calvin and Hobbes strip that the second two rows divide into four equally sized quadrants. This means that if a newspaper wants they can shrink the art down, move the first panel of the second row to the first row, and run the remaining panels as a second row, taking up even less space (while also using the full version of the comic). A similar thing is possible with the Barney Google and Snuffy Smith strip—in its five panel version, panels two and three are equally sized so that it can be run in two rows instead of three, which is the format we discussed it in last year. Other strips are even further compressible—it’s entirely normal for a strip to be comprised of entirely equally sized panels so that it can be rearranged in any sort of grid or even in a single column that can be shoved down the side of a page. (Indeed, so debased is the medium that when I went to find a Sunday comics section to illustrate the ways in which strips are crammed onto the page I discovered that Ithaca’s daily newspaper no longer has a Sunday edition, and that the Sunday funnies are simply no longer sold in Ithaca.)

This is, obviously, no way to treat comics as a medium. And it’s an impressive falling off from the beginning of the newspaper comic, which was in many ways the origin point of the medium. Comics are not something that were straightforwardly invented, instead being gradually refined over the course of the 19th century until they reached something approximating its current form, more or less at the same time it reached popular success, in the form of Richard Outcault’s Hogan’s Alley, originally published in 1895 in the New York World. This feature essentially evolved out of political cartoons into a full-page color features, and saw the standardization of things like speech balloons, if not generally sequential storytelling. Its iconic figure was the Yellow Kid, a young boy, shaved bald, whose dialogue came in the form of words printed on his iconic yellow nightgown.

The key role the Yellow Kid and Hogan’s Alley played was promotional—it was part of the full color supplement published in the paper on Sundays and meant to attract readers and win the heated rivalry between New York World publisher Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst, who in 1896 poached Outcault for his New York Journal. So central was the Yellow Kid to this journalistic rivalry that he became a metonym for the increasingly sensationalistic style of both papers, which became known as “Yellow Kid journalism,” and finally simply “yellow journalism.”

Unsurprisingly, imitators followed. The Katzenjammer Kids, created by Rudolph Dirks and based on the German Max und Moritz, came in 1897, and was the earliest strip to survive into the modern era, running all the way until 2006. By the 1910s, the comics pages were beginning to be populated by strips that are still familiar to the present day: Gasoline Alley, Popeye, and Barney Google and Snuffy Smith itself all date to that decade, while numerous other strips like Little Orphan Annie (1924), Blondie (1930), Dick Tracy (1931) appeared in those early decades. All told, of the ninety-four strips to participate in Cartoonists Remember 9/11, fourteen had been running for over fifty years by 2011.

Discussion of the early days of newspaper strips tends to end up returning to two figures: Windsor McCay and George Herriman, the creators of Little Nemo in Slumberland and Krazy Kat respectively. These were comics that used the luxurious space of the full-size newspaper page—a stunning 16×21 inches in McCay’s case—to its full effect, creating comics of a scope and artistry that have not been matched in the century since, if only because the specific conditions and sort of canvas they worked upon were only available in that narrow stretch of a couple of decades early in the medium’s development. Consider, for instance, the below Little Nemo in Slumberland strip and the way it uses the diagonal across the page for its storytelling, with the arc of Nemo’s tumble completing in the final panel where he wakes up.

Likewise Herriman’s Krazy Kat, a work of inventive surrealism that made its own ambitious use of the page, with an inventive use of negative space that would simply not be possible in later eras of newspaper strips.

These lions of the medium marked a high water mark for newspaper comics—a piece of Americana that stands up a century later as a clear accomplishment and triumph. Alas, the subsequent eight decades are a near unbroken narrative of decline. The first major step was the introduction of the topper—a second, shorter strip run atop the main feature that could be cut by editors looking to include more comic strips. Barney Google, for instance, ran with a topper strip called Bunky, as seen below.

This, clearly, was an antecedent to the cuttable panels in the modern comic strip—a liminal space between the early “full page” comics days and the increasing shrinkage of the modern strip. Eventually the topper was cut entirely because it was preferable to run advertising, or simply more strips. Underlying this was a move from the early days of comics, where they existed as features to sell individual papers, to a syndicate model, where companies would sell libraries of comic strips to papers. In this model, papers could no longer use individual comic strips as exclusives to attract readership, and so instead relied on numerical advantage. Suddenly the full page size of a strip became an impediment, and so the strips moved towards mutability. As the late twentieth century came and went, and the decline of newspapers accelerated, so too did the shrinkage and compression of newspaper strips in an attempt to reduce page counts.

It is not that comic strips form an unbroken narrative of decline—the 1980s, for instance, saw strips like The Far Side, Bloom County, and Calvin and Hobbes revitalize the form, and indeed Bill Watterson used his clout late in the strip’s run to demand that his Sunday strips be run in a half page format that gave him the ability to actually use the medium in ways comparable to what McCay and Herriman had done a half century earlier. (Indeed, note the similarities in how Watterson and Herriman use negative space.

For the most part, however, the comics section became an increasingly conservative section, not simply in the political sense, although Cartoonists Remember 9/11 makes clear the degree to which that is a factor, but in an aesthetic sense. As papers cut page counts to save money an obvious choice became to eliminate comic strips, both to reduce syndication fees and to free up space. But the culling of comic strips inevitably spared the worst of the bunch. Never mind that Blondie or Hagar the Horrible or Beetle Bailey had not been funny once in the last quarter century. They were institutions, and the retirees who increasingly formed the only remaining audience for newspapers would defend them to their last subscription dollar. This quickly became a source of outright infamy among editors—the fact that any effort to cut some old piece of shit comic would be met with a flood of complaints. Which meant that new comics had little to no room to thrive, and those that did largely accomplished it by offering the same sort of comforting vapidity of Hi and Lois or The Wizard of Id.

It is, of course, worth stressing that the newspaper comic is not the only kind of comics in town, nor, more to the point, the only kind of comic strips. By 2011, the medium of the comic strip had been thoroughly revolutionized by the same thing that was accelerating the death of newspapers: the Internet, where anyone with the resources and discipline to create a regular comic strip could do so. It is not, obviously, that there are not bad webcomics. There are in fact very, very many bad webcomics. But there are also countless good webcomics, a renaissance of the form. In particular, while newspaper comics made the basic concessions to diversity that meant that strips like Herb and Jamaal existed to offer Black versions of the bland fare on offer in other strips (although mention must be made of Aaron McGruder’s short lived but incendiary The Boondocks), the funny pages were utterly devoid of queer content, a gap webcomics have filled with style and vigor.

Indeed, in recent years this has even begun to salvage the newspaper medium, as several geriatric strips whose original creators had long since died were handed over to artists from the webcomics scene. This began with the pseudonymous Olivia Jaimes, who took over Nancy after Guy Gilchrist’s execrable twenty-three year run and immediately turned the strip into a massively acclaimed strip by returning to a sense of humor rooted in strip creator Ernie Bushmiller’s sense of whimsy, only updated for the twenty-first century.

This was followed by the arrival of Joey Alison Sayers to update the moribund Alley Oop and, a few years later, Jules Rivera’s revamp of Mark Trail and Randy Milholland’s takeover of the Sunday Popeye strip. This remains a drop in the bucket compared to the number of ancient strips tottering along with no visible talent involved in their creation—John Rose is, for instance, still in charge of Barney Google and Snuffy Smith, which is still utterly devoid of quality. And, of course, the popularity of these strips is largely on the web, which has in general become the primary domain for syndicated comics even as print newspapers continue to lurch along with much the same vigor as Gasoline Alley.

So the 9/11/11 Barney Google and Snuffy Smith strip was not simply a preposterously mawkish piece of crap—it was a preposterously mawkish piece of crap in a nearly century old franchise published in a once majestic but now dying medium where quality had essentially become both impossible and unwanted. There is, obviously, a metaphor here that is worth unpacking. But there’s a more urgent concern, which is the revelation that, in the context in which it actually existed, it was in fact a perfectly good comic strip. I do not mean this claim in any technical or aesthetic sense, but rather in the sense that newspaper comics were definitionally a medium free of any technical or aesthetic ambitions. A project such as Cartoonists Remember 9/11 was designed to create horribly over-sentimental schmaltz, because that’s the only thing that a decayed and bastard medium like the newspaper comic could possibly offer. The 9/11/11 Barney Google and Snuffy Smith strip is terrible, yes, but it was terrible in the precise way it was supposed to be.

But why would anybody want something that is terrible in this precise way?

Next Time: The Only Thing that Stops a Bad Guy with an Emotion is a Good Guy with an Emotion

September 11, 2022 @ 9:08 am

This is a very interesting annual series. I’m from the UK, where aside from Garfield I don’t think we really have any of the strips mentioned in your articles, or at least I don’t remember them growing up. Stuff like Fred Bassett and Rupert Bear were still going when i was a kid. Roy of the Rovers kept coming and going. Most of the strips just felt sub-Beano in terms of sophistication and quality.

I’m surprised there was still so many still in publication in 2011 in both countries given the decline of print media even then.

September 11, 2022 @ 10:03 am

I remember Calvin and Hobbes collections here in the UK, but I don’t think I ever saw them in the paper, no. The only US strips I remember seeing actually in newspapers are Peanuts, Garfield, and I think Spider-Man.

The other ones mentioned I all learned about from the Comics Curmugeon blog.

September 15, 2022 @ 5:54 pm

Actually, Calvin & Hobbes used to run in the Daily Express, sometimes very badly re-lettered to replace American terms with British ones, eg, squirrel for chipmunk. A friend’s parents took the paper and his mother would cut the strips out for me each week, until the next collection was available. And the Guardian re-ran Krazy Kat for maybe six months.

September 11, 2022 @ 6:00 pm

Stuff like Fred Bassett and Rupert Bear were still going when i was a kid.

Fred Basset is still going here in the US, or at least I get Sunday strips in both of my local papers and dailies in the Herald-Mail, though I’ve no idea how old those strips may actually be.

September 11, 2022 @ 9:31 pm

Loving this series. Interesting stuff, especially about how newspaper strips have shrunk over the years.

The Phantom still shows up in the Sunday Mail here in Aus, except it’s been reduced to three panels. Meaning your weeks’ worth of Phantom content boils down to “Phantom hides behind a wall, Phantom jumps over a wall, Phantom says a line of dialogue”. It’s completely pointless, and hilarious to think that anyone might actually be following the story in the way they present it.

November 7, 2024 @ 6:23 am

Oh this is fascinating. I’m loving this series so far. Thank you.