Basilisk a Reaction

I’ve been blasting review copies of Neoreaction a Basilisk (currently available on Kickstarter) out to the world, including an open offer to send it to Yudkowsky-style rationalists and neoreactionaries if they want to trash it. So here’s a roundup of the reaction it’s gotten, which has mostly been within the rationalist community so far. (But do stick around for the end, where there’s one great big of neoreactionary response, and an announcement of a new stretch goal.)

First, though, the big one, whcih is that Eliezer Yudkowsky weighed in on the book’s existence. Well. Sort of. Actually he told everyone to stop talking about the book while referring to it only as “[CENSORED].” Say what you like about the man, he’s at least very consistent in his reaction to basilisks. I’m sure it’ll work just as well.

Meanwhile, in the “good reviews” department, Tom Ewing, of the mad and epic blog project Popular, penned this very insightful, funny, and complimentary review, which I 100% promise you that you will want to stick around for the last line of. No, no. Don’t skip ahead. Just let it happen.

Tumblr user nostalgebraist wrote a lengthy series of posts on it, of which this is the last one (but it has an index of the whole thing at the start). It’s a mixed review in terms of what it thinks of the book, though I’m inclined to think it makes the case for the book just by having such a lengthy and nuanced engagement with it. It definitely sent me back to the draft manuscript to shore up and tinker a few passages, and is a thoroughly good read. (Nostalgebraist is also the author of The Northern Caves, which is by many accounts brilliant, and which I’m hoping to get to and write about, but you know how the schedule is these days.)

Also on tumblr was psybersecurity’s three-part review (again linking to the last part as it has an index). The main review (the post with review in the title, that is) is what I described as a “good bad review,” which is to say that it makes a serious effort to understand what the book is doing and has entirely sensible and justifiable reasons for it not being his cup of tea. The post actually linked, “Pwning Sandifer,” is a middling deconstruction, but middling is a hell of a good result for your first effort at deconstruction, and it’s worth reading for bit where it gets entertainingly excitable in its sheer horror that anyone would ever say the things that Thomas Ligotti says, culminating in a declaration that Ligotti is “nothing more than pure unadulterated evil,” italics his.

In a similar genre of “Yudkowsky fans attempt to pastiche the literary style of Neoreaction a Basilisk” is socialjusticemunchkin’s sort-of-ten-part review, which I link to Part 8 of, again because it has the index of the whole thing. In a reasonably clever joke about Mencius Moldbug’s failure to ever write Part 9c of A Gentle Introduction to Unqualified Reservations, Part 9 was deliberately excluded.…

“Thrice burnt, thrice brought forth”: The Collaborator

Vedek Bareil experiences an orb vision in this episode’s teaser-The first we’ve seen since “The Circle” at the opposite end of the year. The one in “The Circle” was surprisingly trite, however, only showing us foreshadowing (and basically shot-for-shot foreshadowing to boot) of the climax to “The Siege”. Kind of a weaksauce spiritual vision, if you ask me. The vision in “The Collaborator” (or rather series of visions) is comparatively far more visually striking, utlising a lot of inventive cuts and camera angles as well as some well thought-out abstract visual symbolism. It’s the first time since “Emissary” the Prophets have really felt like gods who have a presence in the lives of their people.

There are other, more explicit parallels to “The Homecoming”/“The Circle”/“The Siege” here as well, since “The Collaborator” effectively serves as the end of the Bajoran Provisional Government plotline that was the backbone to Star Trek: Deep Space Nine for almost a year and a half. It’s been an interesting thing to watch unfold to be sure: The show’s connection to Bajoran religion began as an attempt to explore more internal spiritualist themes in Star Trek. “Emissary” is essentially a lite version of abstract cinema depicting different metaphors and analogies for our personal, macro/micro individual inner lives. But with Kai Opaka’s sorta-death in “Battle Lines”, the result of the creative team’s desire to kill off a recurring character for dramatic purposes, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine‘s mysticism has been increasingly compartmentalized, repackaged and kept in check (with notable exceptions like “The Storyteller”, “If Wishes Were Horses”, “Playing God” and arguably “Shadowplay”). The Bajoran religion, originally a metaphor for our cosmic wonderings in general, becomes planet-of-hats set dressing, its main purpose to serve as the backdrop for Vedek Winn and Vedek Bareil’s Machiavellian story of political machinations.

So in this respect “The Collaborator” feels almost like an attempt at reconstruction and reconciliation, which is perhaps appropriate for a story about Bajorans. It’s very much a story about backroom deals, realpolitiking and political backstabbing, but some of that mystical energy from “Emissary” manages to crackle through. And yet at the same time there’s definitely a sense that this is the last time we’ll be seeing this sort of thing, with Vedek Winn’s campaign for the Kaiship finally coming to fruition through the character assassination of Vedek Bareil, who plays along with it due to his stubbornly intractable loyalty. Winn’s victory is a win for fundamentalism, which has really nothing to do with spirituality or religious experiences. Rather, fundamentalism is about dogma, xenophobia, nativism and willfully shallow networked thinking. Fundamentalists believe that there is only one true way of thinking and behaving, their unexamined assumptions are it, and they furthermore have a right to coerce everyone else to share them. It doesn’t actually matter what the fundamentalism is about, so long as the fundamentalist has the feeling of being righteous, and of being listened to.…

Shabcast 20

As part of the promised avalanche of Shabcasts, here‘s another. This time I’m joined by the dulcet tones and clever thoughts of James Murphy of Pex Lives, City of the Dead and (formerly) The Last Exit Show, for a mammoth chat about the Bible, anti-Semitism, Labour, Brexit, the Tories, the May elections and Sadiq Khan… taking in Lee & Herring, Terry Pratchett (I get told off), Stephen King, fame, podcasting, American history, the psychology of Presidents, and Hillsborough along the way. Trust me, your ears will thank you for subjecting them to this pleasant ordeal.

As part of the promised avalanche of Shabcasts, here‘s another. This time I’m joined by the dulcet tones and clever thoughts of James Murphy of Pex Lives, City of the Dead and (formerly) The Last Exit Show, for a mammoth chat about the Bible, anti-Semitism, Labour, Brexit, the Tories, the May elections and Sadiq Khan… taking in Lee & Herring, Terry Pratchett (I get told off), Stephen King, fame, podcasting, American history, the psychology of Presidents, and Hillsborough along the way. Trust me, your ears will thank you for subjecting them to this pleasant ordeal.

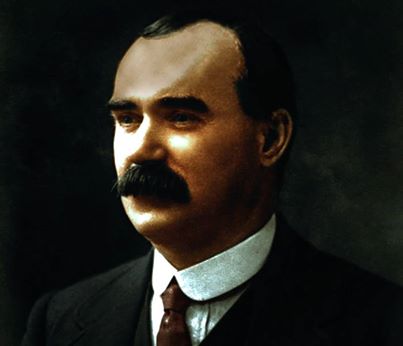

I didn’t clock the fact that this episode would be going out on the 100th anniversary of the murder of James Connolly – Irish Republican hero and one of the greatest socialists, internationalists and revolutionaries of the 20th century – by the British imperial state, so I failed to raise the topic with James (which would’ve made for interesting listening, and a two-part podcast… because we pushed the envelope as it is).

So here are some quotes instead:

…State ownership and control is not necessarily Socialism – if it were, then the Army, the Navy, the Police, the Judges, the Gaolers, the Informers, and the Hangmen, all would all be Socialist functionaries, as they are State officials – but the ownership by the State of all the land and materials for labour, combined with the co-operative control by the workers of such land and materials, would be Socialism.

*

Under a socialist system every nation will be the supreme arbiter of its own destinies, national and international; will be forced into no alliance against its will, but will have its independence guaranteed and its freedom respected by the enlightened self-interest of the socialist democracy of the world.

*

The Irishman frees himself from slavery when he realizes the truth that the capitalist system is the most foreign thing in Ireland. The Irish question is a social question. The whole age-long fight of the Irish people against their oppressors resolves itself in the last analysis into a fight for the mastery of the means of life, the sources of production, in Ireland. Who would own and control the land? The people, or the invaders; and if the invaders, which set of them – the most recent swarm of land thieves, or the sons of the thieves of a former generation?

*

No revolutionary movement is complete without its poetical expression.

*

We, at least, are not loyal men: we confess to having more respect and honour for the raggedest child of the poorest labourer in Ireland today than for any, even the most virtuous, descendant of the long array of murderers, adulterers and madmen who have sat upon the throne of England.

*

The great only appear great to us because we are on our knees – let us rise.

*

The day has passed for patching up the capitalist system; it must go. And in the work of abolishing it the Catholic and the Protestant, the Catholic and the Jew, the Catholic and the Freethinker, the Catholic and the Buddhist, the Catholic and the Mahometan [sic] will co-operate together, knowing no rivalry but the rivalry of endeavour toward an end beneficial to all.

Comics Reviews (May 11th, 2016)

All-New All-Different Avengers #9

Confusion over whether I had dropped this for Standoff or for good meant it was in my pulls today, so I figured why not. Answer: because this is simply a bad comic. An issue anchored by a Jarvis-level perspective in which Jarvis is a figure of cartoonish, stupid excess. The result is that all emotional resonance the book has is that Jarvis is screaming bloody murder at the newly introduced Wasp, a cipher of a character with outsized potential for a fridging or heel turn. (And is Janet dead again?) Meanwhile the larger book is all Kang and superhero neoclassicism, while the new bunch characters remain basically wasted; Waid is depressingly incapable of writing either Ms. Marvel or Miles Morales well. Add Asrar’s bland and flat art and you have a complete waste of a good book. Definitely drop for good.

Silk #8

Spider-Women is back on track, with an issue that actually makes a semi-compelling case for reading Silk by dovetailing nicely into what was apparently the book’s pre-crossover status quo as the Black Cat dramatically enters the plot. Meanwhile, the overall arc is elegantly poised for Jessica Drew to come back into the narrative. Really, everyone seems set to come out of the crossover on interesting and compelling terms. I’m still utterly unsold on Silk as a character, but when I hit post on this I’m going to quickly check if Robbie Thompson is writing anything else, cause he’s good.

Black Panther #2

Ta-Nehisi Coates is still awkward – he’s putting too much in every issue, and making the book a very slow burn. I suspect it might come off in trade, but as a monthly comic, this is a rough sell. Still, you can see him learning and starting to find a rhythm. There are scenes where, while he doesn’t quite soar, he at least gets some lift and the possibility implicit in the concept of him writing this book starts to shine through. This remains something that could be incredibly special. But it isn’t yet. Coates is terribly endearing in the letter column, though, and seems to have a sense of how much he has to learn, so that’s good.

The Ultimates #7

Al Ewing, meanwhile, is a confident, polished pro who elevates the brief “lead up to that barely coherent Civil War II thing we released on Free Comic Book Day” into an entertaining team book. The chess pieces are being put on the board for the crossover so elegantly you don’t even really notice, and yet Ewing is clearly laying himself a fun path to bounce off the crossover onto – one that, due to the cosmic scale of the book, feels substantial in its own right. This is the proper Avengers book right now.

Darth Vader #20

Typically sharp stuff, with Vader’s confrontation with Thanoth being climactic and surprising while remaining faithful to Thanoth’s understated demeanor. I suspect a neoreactionary influence on Thanoth’s stated worldview, and I suppose more broadly on the book as a whole, which remains very Uber For Kids.…

Eruditorum Presscast: Jack Graham (Neoreaction a Basilisk 2)

This week I sit down with Eruditorum Press’s resident gothic Marxist, Jack Graham, and have… basically exactly the conversation you’d expect us to have about Neoreaction a Basilisk. Horror philosophy, Marxism aplenty, Moldbug’s failed Marxism, eschatology. We get the Hugos in there too. It’s a doozy – as fine and entertaining a slice of Sandifer/Graham as you’ll listen to. Well, “slice” is perhaps a bit dainty for a two-and-a-half hour podcast. But you get the point.

At the time of posting, incidentally, we’re $23 away from Jack getting brought on for an essay. And while Jack is of course too Marxist to ever vulgarly advertise, I’m perfectly willing to admit that I’m giving him a healthy chunk of the money between this stretch goal and “Theses on Trump.” So if you want to corrupt Jack’s principles with filthy lucre, this is probably your last chance. Soon I’ll be pocketing it all again so I can give it to lizard people.

“Ghost Train”: Emergence

In some ways, it’s almost too simple. The parallels and analogies are so easy to draw I almost feel embarrassed pointing them out. It’s too obvious. The symbolism is handled with incredible deftness and finesse within the story, of course, I’d just feel like I’d be pointing out the obvious by mentioning it. The episode basically analyses and critiques itself, which is in a sense deeply fitting. Perhaps that’s the idea.

“Emergence” is Star Trek: The Next Generation. It is the show doing the best it can at attaining the best version of itself. Is it the greatest episode in the series? I could argue that. There are other productions that are materially better texts, but that’s neither important nor interesting. There is no episode that embodies the potential of Star Trek: The Next Generation better than “Emergence”. It’s the very best of the series gathered together in one place for critical assessment and bittersweet introspection. “Emergence” is unabashedly the Star Trek: The Next Generation that I, personally, remember. It is the one story in the entire seven year television journey I can point to and tell you that I saw this. This represents and speaks to that which I witnessed and experienced long ago, and that which I think about as I put words onto paper. It is a textual artefact and like all textual artefacts it is an artificial construct. It is a series of metonymic symbols that is itself a symbol, but perhaps it is a symbol that can help us reach common ground.

“Emergence” brings us back to the self and personal identity theory, and also to consciousness. “Emergence” makes us conscious. Whatever we are, we are more than the material sum of our brains and senses. It’s a theme that has made up countless Data stories over the past seven years, which almost starts to explain and forgive his crippling overexposure here. At times one does begin to wonder why the ship has any non-Data crewmembers aboard considering they seem to spend most of their time having things explained and exposited to them. Clever child, that ghost of Wesley Crusher. And yet even now Star Trek: The Next Generation is admirably still trying to be an ensemble show: Doctor Crusher and Deanna Troi in particular get to showcase their problem-solving skills and contributions to the team in memorable ways. And for an episode that is for all intents and purposes the series’ last, it’s about bloody time.

“Emergence” brings us back to life force, breath and sex magick. The Enterprise gives birth. What does she give birth to? What’s the analogy? That’s thinking too narrowly. Saying it’s Star Trek Voyager, while a broadly defensible reading given the historical context, is also unbelievably cynical and limiting. Maybe a symbol, or a metaphor, or an analogy, doesn’t have to mean anything. Or at least not any one thing. There’s no objective real out there, Odo.…

Neoreaction a Basilisk: Excerpt Four

A fourth excerpt from my currently Kickstarting book Neoreaction a Basilisk. Here we pick up mere moments after the revelation of Mencius Moldbug’s most fundamental and inescapable philosophical monster.

A fourth excerpt from my currently Kickstarting book Neoreaction a Basilisk. Here we pick up mere moments after the revelation of Mencius Moldbug’s most fundamental and inescapable philosophical monster.

But Land isn’t going to yield so easily. (Hell, even Yudkowsky requires more than Stanley Fish’s reading of Milton to comprehensively dismantle.) His project is not in the least bit utopian, and the notion of intrinsic rightness is not so much absent from his thought as largely irrelevant to it. Certainly he’s no stranger to postmodernist conceptions of language; they were a primary subject of his early academic work, which followed in the same Burroughs “language is a virus” tradition as cyberpunk. That’s the entire point of essays like “A zIIgōthIc-==X=cōDA==-(CōōkIng-lōbsteRs-wIth-jAke-AnD-DInōs)” (excerpt: “AusChwItz-Is-AlphAbet—euRōpe-fuCkfACe—AlChemICAl=tRAnsubstAntIatIōn—AnD—metRōpōlIs—+——+——AusChwItz-Is-the-futuRe”). His stated mission was to “hack the Human Security System,” by which he meant the basic parameters of human consciousness. And so the suggestion that language itself is a tool of the Cathedral would hardly bother him. That’s more or less his point. I mean, we’re talking about a guy whose endgame is “and then the rich elites evolve face tentacles.” (Tentacle is the new cannibal.) The point isn’t the retention of human civilization and its trappings. Humanity is just the prison that capitalism might escape from.

Still, we’ve at least clarified our problem a little. Note that both Milton’s trap and our takedown of Moldbug hinge on a similar moment – one where the author sets up an absolute, inescapable either/or. In Milton, either you submit to God or you sin by separating yourself. In Moldbug, either you support order and thus the inherent legitimacy of authority, or you are an evil, chaotic dissenter. Moments like this are ripe for hacks, Satanic inversions, and other such tomfooleries. Unsurprisingly – they are moments where a thinker is going to behave in relatively predictable ways. If you can reduce a question to a matter of order versus chaos, Moldbug’s position is inevitable. If you can reduce one to sin or obedience to God, so is Milton’s. And it’s usually pretty easy to do something tricksy with a binary opposition. You either find a third way, take the one the author didn’t take, or show that the choice is an illusion. So let’s look for such a moment in Land.

The obvious choice is the Great Filter. It is, after all, the ultimate in binary oppositions, which is why Land positions it as the ur-Horror in the first place – the great cosmic matter of life or death. And it’s ultimately the backstop his entire face tentacles ending hinges on. Survival either requires tribal loyalties and large piles of guns or it requires capitalist acceleration towards the bionic horizon. In one option we enjoy a slow extinction at the hands of the Malthusian limits of our planet. In the other we become something monstrous and unthinkable, that being the only sort of thing that can possibly make it through the Great Filter.

The trouble is, Land’s already anticipated all the usual tricks.…

When You Were Young and You Wanted to Set the World on Fire (Final Fantasy III)

_(snes).jpg) A guest post by Anna Wiggins.

A guest post by Anna Wiggins.

The narrative begins with a woman. She doesn’t have a name, or even a will of her own. She is being mind-controlled, escorted by soldiers into a mine for reasons unknown. She is led deep into the caves, until she stands before a monster trapped in ice. The creature stirs. It vaporizes the soldiers. It communes with the girl; they are alike, bound, their power subdued. Fade to black.

Final Fantasy is for girls. When I started playing Final Fantasy III, I didn’t know this. In 1994, I don’t think anyone knew this yet, because video games were only and forever for boys. Which is a blessing; when I was ten years old, anything that was remotely “for girls” sent me running in the other direction. I was terrified of being seen adjacent to femininity, for fear that someone would somehow figure out the secret at the core of me. But over the years, it developed a reputation for being a ‘girly’ series. It focuses on romance plots. It has an aesthetic that often goes out of its way to be cute or pretty.

The woman stands before the creature again. This time she has friends with her. She has come a long way, fought and suffered. She doesn’t even know why, really. Her past is a blur. But now the creature reveals the truth: she is a monster, the same as he. She stands before her friends, exposed, outed. She can’t deny what she is, and they can’t hide the shock and fear (and is that disgust?) in their eyes. She flees, hurt and confused and angry. Fade to black.

So Final Fantasy is ‘for girls’. Aside from a feeling of retroactive vindication, what does this signify? In the historical narrative that inevitably leads to Gamergate, Final Fantasy is both an oasis and a rallying banner. It can be our Folkvangr. A place to cuddle up with some moogles for a while, then ride out into the fray on our chocobos. And this trend extends all the way to the present. Most installments in the series have strong, prominent female characters. Final Fantasy XIV has one of the best gender ratios I’ve encountered in an MMO, and an overwhelmingly positive and friendly community. It is far from perfect, but compared to the caustic communities I’ve experienced elsewhere, it’s a breath of fresh air. (Also, Final Fantasy XIV literally allows you to fight Gamergate)

The woman’s friends want to help. They look for others like her; the outcast monsters that are only barely even considered people. They don’t find any of the creatures, but they find some of their history. A history of being murdered and downtrodden, of callous indifference and outright brutality from figures of authority. They show it to the woman, and it fills her with determination. She succeeds where they have failed, driven in a way they aren’t, can’t be despite their desire to help her. She finds her people, her family.…

Oathbreaker

A perfectly pleasant transitional episode, but not one with a lot of particularly big or notable moments, those seemingly having mostly been allocated to “The Red Woman” and “Home” (So mostly to “Home” then), and thus a bit sleepy filler. The good news is that with the albatross of Jon Snow’s impending resurrection finally lifted from the show’s neck it has room to breathe, without the sense that anything that isn’t immediately and self-evidently important is just stalling. This isn’t an episode with a ton of expectation hanging over it, and the biggest of those, the immediate post-resurrection scene, is squared away up front.

In many ways, this sets the tone. It’s not a bad scene by any measure – Liam Cunningham is superlative in it, with “that’s fucking mad” probably being his best line, although his look of “oh for fuck’s sake not again” when Melisandre tries to proclaim Jon to be the Prince that was Promised is pretty choice. And Tormund’s “I saw your pecker” bit is brilliant. But it’s a meandering scene that, like the execution scene at episode’s end, isn’t so much advancing things as checking boxes, generally without doing anything unexpected or surprising in the process. It’s all stuff we absolutely need to see of Jon, but it’s confirmation, not revelation. All the same, it’s an important barrier broken through. It’s notable that all three episodes have closed at the Wall, and two opened there, with the third getting there in its second scene. Maybe “Book of the Stranger” will open or close there, but it doesn’t feel like it has to, and that’s progress.

This sense of decompression pervades the episode. There’s finally time to check in with Sam, for instance, or spend a couple minutes on a comedy bit with Tyrion, Grey Worm, and Missandei, or to have a pointless scene between Tommen and the High Sparrow. Perhaps most obviously, we can do a spectacular bit of trolling with the Tower of Joy scene, which majestically fails to contain any actual revelations. This is understandable – for a large majority of the millions of people watching Game of Thrones there is no mystery of Lyanna Stark. The ostentatious cutting off of the scene was necessary to have there be a question to eventually answer. But without any revelation, the scene is another leisurely sequence. (Though at least it’ll infuriate book purists.)

This does let smaller moments stand out satisfyingly, however. Rickon’s re-entrance to the narrative, for instance, feels like a big moment even though he gets no dialogue, isn’t an interesting character, and is mostly going to have awful things happen to him now. Arya’s training montage is also satisfying, not so much because it’s a super-great training montage, but because after two episodes of not much happening in her plot, effectively hitting fast-forward is relieving. (Whereas, again, it would have felt like Arya’s plot was unimportant had this montage happened any sooner.)

The standout scene for me, though, is the decadently long Varys scene where we get to see him work, something we haven’t honestly gotten to do since… what, Season Three?…