Creature from the Black Lagoon

Last week we talked about the expression of the Beautiful throughout the history of Doctor Who, and gleaned different kinds of aesthetics employed by the show in the process – from awe at new, strange places… to the banal objectification of women… to an almost ritualized praise of monsters in the modern era. And it’s this latter sense of beauty that I find most interesting, given how monsters are now used in Doctor Who, especially in the Moffat era. Because monsters are no longer just villainous plot devices for generating scares. Quite often they are secret protagonists, and weighted with symbolic value, especially when juxtaposed with our main characters such that they become telling metaphors. This latter process I call the “monstering” of a character, and of particular interest to me is how Amy Pond becomes consistently monstered during her time on the show.

Last week we talked about the expression of the Beautiful throughout the history of Doctor Who, and gleaned different kinds of aesthetics employed by the show in the process – from awe at new, strange places… to the banal objectification of women… to an almost ritualized praise of monsters in the modern era. And it’s this latter sense of beauty that I find most interesting, given how monsters are now used in Doctor Who, especially in the Moffat era. Because monsters are no longer just villainous plot devices for generating scares. Quite often they are secret protagonists, and weighted with symbolic value, especially when juxtaposed with our main characters such that they become telling metaphors. This latter process I call the “monstering” of a character, and of particular interest to me is how Amy Pond becomes consistently monstered during her time on the show.

But what does it mean “to be monstered?” What does that look like? And how unique is it to the modern era? To answer those questions, I’ll step briefly back into the past, to The Android Invasion, aa 4th Doctor story with Sarah Jane in Season 13. In The Android Invasion the Doctor and Sarah Jane have landed on an alien planet that looks like Earth, but it isn’t Earth, it’s the staging ground for an alien invasion that will use android duplicates of certain Earthlings, which is pretty standard Doctor Who fare when you think of it. Anyways, there’s this great cliffhanger where Sarah Jane has been replaced by an android duplicate, only the Doctor has figured it out and attacks her, wrestling her to the ground. Her face falls off, revealing so much circuitry.

Yes, this the best moment in the otherwise fairly dreadful tale (it was written by Terry Nation, for gods’ sakes), but it’s also freighted with some potentially interesting literary readings. First of all, Sarah Jane isn’t the only android duplicate – there’s some regular UNIT personnel, and even the Doctor, all monstered by androids. It’s uncanny because we see characters we’ve known as “good” behaving in ways that are “not good,” which is rather transgressive. Aside from that, though, there’s the opportunity for the nature of the particular monster to inform us about our characters’ natures. This works particularly well in the monstering of Benton and Harry – they’re programmatic characters. Sadly, Terry Nation is not a particularly writerly writer, as the monstering of both the Doctor and Sarah Jane really don’t say much about them at all – well, unless we stretch it a bit. For example, Sarah Jane’s role as a Companion is often programmatic, from assisting in asking questions for the audience to serving as a plot device. And even the Doctor, well, it’s a role that could be (and has been) played by all kinds of performers, such that he doesn’t even have a real face anymore.

Contrast this with the monstering of Amy in Night Terrors. In Night Terrors, we see Amy transformed into a deadly Wooden Doll, the product of a child’s nightmare, a child who’s afraid of being abandoned. This, of course, is precisely Amelia’s sacred wound, the little Scottish girl alone in England, alone in that big empty house with missing parents and a Doctor who doesn’t come back in five minutes but is twelve years late instead. Furthermore, Amy’s transformation into a monster comes right on the heels of this dialogue:

Contrast this with the monstering of Amy in Night Terrors. In Night Terrors, we see Amy transformed into a deadly Wooden Doll, the product of a child’s nightmare, a child who’s afraid of being abandoned. This, of course, is precisely Amelia’s sacred wound, the little Scottish girl alone in England, alone in that big empty house with missing parents and a Doctor who doesn’t come back in five minutes but is twelve years late instead. Furthermore, Amy’s transformation into a monster comes right on the heels of this dialogue:

AMY: We can’t stay in here. We’ve got to get out!

RORY: Er, how?

AMY: Take control, Rory. Take control of the only thing we can. Letting them in.

RORY: Letting them in?

AMY: It’ll surprise them. We open the door and we push past them. Kick them, punch them, anything, okay?

Amy proposes to let the monsters in and combines it with a vow of unmitigated violence. Of course the text needs to monster her. And the thing is, it’s not unusual for Amy to use violence – this is a part of her character, whether she’s biting psychiatrists or telling Rory to whack an old woman (who, admittedly, has a venomous snake-eye monster living in her throat) or shooting the Doctor in the forehead. But here we get an instance of the text admitting that this character trait is something that makes Amy herself monstrous, by virtue of juxtaposition.

Doctor Monster

Lest you think this is an indictment of Moffat’s handling of a female character, we should point out that monstering is not a process that’s exclusive to Amy in this period of the show. Not at all. In fact, throughout most of Series Five, it’s the Doctor who gets monstered, not Amy, and even Rory gets monstered at the end of the season when he comes back as a Roman soldier who’s really plastic Auton that shoots Amy dead.

Lest you think this is an indictment of Moffat’s handling of a female character, we should point out that monstering is not a process that’s exclusive to Amy in this period of the show. Not at all. In fact, throughout most of Series Five, it’s the Doctor who gets monstered, not Amy, and even Rory gets monstered at the end of the season when he comes back as a Roman soldier who’s really plastic Auton that shoots Amy dead.

Consider how often the Doctor is monstered in this season, and how deliberately. Right out of the gate (we’ll return to The Eleventh Hour and Prisoner Zero in a little bit) we get The Beast Below, where the juxtaposition of the Doctor and the Star Whale is made explicit in the climactic exposition delivered by Amy:

DOCTOR: Amy, you could have killed everyone on this ship.

AMY: You could have killed a Star Whale.

DOCTOR: And you saved it. I know, I know.

AMY: Amazing though, don’t you think? The Star Whale. All that pain and misery and loneliness, and it just made it kind.

DOCTOR: But you couldn’t have known how it would react.

AMY: You couldn’t. But I’ve seen it before. Very old and very kind, and the very, very last. Sound a bit familiar?

Obviously, as conceived in this story, the “monster” isn’t just a figure to scare the kiddies. By the time we get to the story’s resolution, the monster is an entirely sympathetic creature; it’s the people, from the police to Liz X, who are the real villains. And this actually extends to everyone on Starship UK, everyone who votes to forget their complicity in the torture of the monster (which is both fair and not fair, as Jack has likely pointed out elsewhere). Monsters are people, and people are monsters – hence the “Winders” who bear both human and monstrous faces.

This juxtaposition of the Doctor and the monster isn’t always as “kind” as this one. In Victory it’s only the recognition of the Doctor who can verify the identity of the Daleks; their identities are intertwined, going all the way back to Power of the Daleks. (Winston, btw, is called a “beauty” and hence is also linked to the monstrous.) Amy, on the other hand, is presented as simply Doctorish, whether it’s catching Winston’s sleight of hand to defusing the Bracewell bomb by getting him to remember love alongside the memories of pain that the Doctor was focusing on. In Crash of the Byzantium both the Doctor and River are juxtaposed with the Weeping Angels by virtue of all being “complicated space-time events.” It’s the Doctor who is juxtaposed with Lady Calvierri in Venice – both are (again) the last of their kinds, and both sit on the technological throne-room chair. The Dream Lord in Amy’s Choice is really the Doctor. We get another of these “only one of its kind” monsters in Vincent, where the Doctor sees the blind monster only while looking in a mirror. And of course, in The Lodger the monster comes from the controls of a chameleonic dimensionally transcendental time machine looking for its “pilot” (which also, deliciously, monsters the TARDIS).

This juxtaposition of the Doctor and the monster isn’t always as “kind” as this one. In Victory it’s only the recognition of the Doctor who can verify the identity of the Daleks; their identities are intertwined, going all the way back to Power of the Daleks. (Winston, btw, is called a “beauty” and hence is also linked to the monstrous.) Amy, on the other hand, is presented as simply Doctorish, whether it’s catching Winston’s sleight of hand to defusing the Bracewell bomb by getting him to remember love alongside the memories of pain that the Doctor was focusing on. In Crash of the Byzantium both the Doctor and River are juxtaposed with the Weeping Angels by virtue of all being “complicated space-time events.” It’s the Doctor who is juxtaposed with Lady Calvierri in Venice – both are (again) the last of their kinds, and both sit on the technological throne-room chair. The Dream Lord in Amy’s Choice is really the Doctor. We get another of these “only one of its kind” monsters in Vincent, where the Doctor sees the blind monster only while looking in a mirror. And of course, in The Lodger the monster comes from the controls of a chameleonic dimensionally transcendental time machine looking for its “pilot” (which also, deliciously, monsters the TARDIS).

Now, this is not to say that there isn’t any monstrous juxtapositions for Amy in this season. Obviously, The Eleventh Hour has Prisoner Zero showing up not just as the Doctor, but as the Doctor with little Amelia holding onto his hand. Amy’s the one who risks killing everyone on Starship UK, taking Liz’s hand and forcing her to press the ABDICATE button – given Liz’s “Little Red Riding Hood” outfit and Amy’s own innate ginger qualities (not to mention her outfit in Crash of the Byzantium), she’s juxtaposed with the monstrous forces of Liz’s regime. Speaking of the Byzantium, an Angel tries to crawl out of Amy’s eye, threating to turn her into an angel herself. Amy begins “vampire conversion therapy” in Venice, her indecision regarding Rory and the Doctor in her titular “choice” episode frames the story’s dilemma (she even tries to commit double-suicide with the Doctor), and the clothing choices of the awful, violent Ambrose in The New Silurians also creates a juxtaposition with Amy, who takes up arms in the underground labyrinth at her first opportunity. But these are all in the background, so to speak.

Pond Scum

RIVER: A box, a cage, a prison. It was built to contain the most feared thing in all the Universe.

DOCTOR: There was a goblin, or a trickster, or a warrior. A nameless, terrible thing, soaked in the blood of a billion galaxies. The most feared being in all the cosmos. And nothing could stop it, or hold it, or reason with it. One day it would just drop out of the sky and tear down your world.

Which brings us to the Pandorica. The occupant of the Pandorica is described pretty much as a monster. Naturally, then, it’s the Doctor who ends up inside, the terrible blood-soaked thing that creates fear everywhere. But when we get to The Big Bang, it’s not just the Doctor who sits in the chair. No, the big reveal at the beginning of this episode is that the Pandorica’s occupant is Amy. Who, by association, is now some kind of goblin, or trickster, or warrior. She’s a nameless thing – she goes through at least four different names during her time on the show – and her death at the end of The Pandorica Opens coincides with the destruction of a billion galaxies. You can’t stop her, or hold her, or reason with her.

And this juxtaposition of Amy and monstrosity kicks into overdrive once we get to Series Six. Because now her darker qualities and the visuals of her monstering become quite overt. Consider The Impossible Astronaut, where she takes the gun of an FBI agent and shoots the Apollo astronaut, who is actually her daughter. I mean, come on, that’s dark. Almost as dark as the suit she wears in the next episode, which visually aligns her with the “men in black” Silence. Such costuming choices continue in Curse of the Black Spot, when Amy dons pirate apparel. Now, the pirates themselves aren’t the most monstrous monsters of the story – the Siren ostensibly is, but she’s a metaphor for River Song. However, the pirates aren’t exactly heroes, but self-centered thieves who take their bounty by force. Amy, of course, uses violence to try and rescue the Doctor, but ends up wounding Rory in the course of her swordplay.

JENNIFER: When I was a little girl, I got lost on the moors, wandered off from the picnic. I can still feel how sore my toes got inside my red welly boots. And I imagined another little girl, just like me, in red wellies, and she was Jennifer too. Except she was a strong Jennifer, a tough Jennifer. She’d lead me home. My name is Jennifer Lucas. I am not a factory part. I had toast for my breakfast. I wrote a letter to my mum. And then you arrived. I noticed your eyes right off.

RORY: Did you?

JENNIFER: Nice eyes. Kind.

RORY: Where is the real Jennifer?

JENNIFER: I am Jennifer Lucas. I remember everything that happened in her entire life. Every birthday, every childhood illness. I feel everything she has ever felt and more. I’m not a monster! I am me. Me! Me! Me!

One of the most exquisite “monsterings” of Amy comes in The Flesh two-parter, when Amy is juxtaposed with Jennifer – specifically, with the Jennifer that’s a Flesh monster. Some of this visual – Amelia Pond, after all, wore red wellies when she waited for the Doctor to return in her garden all those years ago. And then there’s what’s going on with Rory – is he becoming Jen’s boyfriend? She’s certainly positioning herself into a relationship with Amy’s lover. And of course, it’s revealed that the Amy in this episode is actually of the Flesh herself – a veritable monster in her own right.

To some extent, it’s deserved. I mean, this episode is all about consciousness, and how consciousness is what makes a person a person, not the particulars of their embodiment. Not to say that embodiment doesn’t play a huge role in who someone is, but it doesn’t matter whether someone’s Flesh or blood and bone, they’re still a person, still deserving of respect, respect for the consciousness behind those eyes. The lack of this compassion is what makes Jen a monster. Well, Amy also shares this lack  when it comes to the Flesh Doctor. It’s her major lesson in this story, but it’s still a monstrousness she had to work through (unlike Rory, for example).

when it comes to the Flesh Doctor. It’s her major lesson in this story, but it’s still a monstrousness she had to work through (unlike Rory, for example).

Sometimes Amy’s monstering is so, so subtle, like in A Good Man Goes to War. In this scene, Colonel Runaway is giving his speech on the Doctor, and how permission has been granted to reveal the true nature of a Headless Monk. Just as his says that the Papal Mainframe Herself has made this decree, we cut to a shot of Amy looking out at the proceedings (through a window with a rather Star Warsy aesthetic). The juxtaposition, then, is between Amy and the Papal Mainframe, which was apparently behind this religious witch hunt of the Doctor. And again, there’s a monstrousness to Amy in this story – her desire to take Lorna Bucket’s gun, for example, or declaring she’s armed and dangerous (she actually wields a pipette). Notice, too, that the Doctor is also monstered here – he literally appears as a Monk, and of course is acting from his heart without the benefit of his head.

We’ve already talked about Night Terrors, and how Amy’s turned into a monster upon suggesting violence as a resolution to conflict management, so we’ll cast our gaze next on The Girl Who Waited, where an older Amy lost in the Two Streams facility has turned into a monster. I mean, she’s constantly doing all this violent swordy stuff, yeah. But just look at her – she’s now wearing bits and pieces of the episode’s ostensible monsters, the Handbots, and in the heart of the episode there are several shots of her juxtaposed with her other self, such that she appears to have two heads. She’s not the only one monstered in this episode – one of the Handbots is called Rory, but he doesn’t have any hands – he’s lacking the ability to anesthetize anyone at this point. In the violent climax in the Art Gallery, there’s a great shot where Rory bashes a Handbot with a painting of the Mona Lisa, and he’s positioned such that he practically mirrors the robot.

We’ve already talked about Night Terrors, and how Amy’s turned into a monster upon suggesting violence as a resolution to conflict management, so we’ll cast our gaze next on The Girl Who Waited, where an older Amy lost in the Two Streams facility has turned into a monster. I mean, she’s constantly doing all this violent swordy stuff, yeah. But just look at her – she’s now wearing bits and pieces of the episode’s ostensible monsters, the Handbots, and in the heart of the episode there are several shots of her juxtaposed with her other self, such that she appears to have two heads. She’s not the only one monstered in this episode – one of the Handbots is called Rory, but he doesn’t have any hands – he’s lacking the ability to anesthetize anyone at this point. In the violent climax in the Art Gallery, there’s a great shot where Rory bashes a Handbot with a painting of the Mona Lisa, and he’s positioned such that he practically mirrors the robot.

One might think that this is the actual climax of Amy’s monstering. After all, in the next episode, The God Complex, it’s once more the Doctor juxtaposed with the episode’s central monster, be it early on when he’s positioned under a set of horns on the wall, or mirrored against the monster in the Beauty Spa (a BEAUTY spa!), or when the Minotaur’s dialogue as he dies implicates both Doctor and monster. Amy, she’s just someone who’s fallen under the monster’s spell. Well, except for this weird scene where she’s saving the fish from the Beauty Spa, only for them to be eaten by Gibbis… a shot that resonates with the final imagery of Amy looking out her window while the Doctor’s face seemingly bobs in the glass time rotor of his TARDIS. Fish swim in ponds, right?

Likewise, in Closing Time, there’s nothing about Amy and Cybermen – this time it’s Craig who’s monstered, obviously because he struggles to form an emotional bond with his child. But there’s just a tiny bit of Amy in this episode – we see her massive eye staring out of a massive poster on the wall in a department store, in service to a perfume called Petrichor, which evokes the scene in The Doctor’s Wife where she solves the password to the auxiliary control room using the power of her imagination. If anything, Amy’s juxtaposed with the TARDIS here, not a monster.

Well, except that the TARDIS herself gets monstered in that episode, as her embodiment gets taken over by The House. You know, we actually elided that episode earlier, but now that Amy’s been juxtaposed with the TARDIS, we might as well explore any timey-wimeyness going on here, because frankly there is some timey-wimeyness to Closing Time and The Wedding of River Song. See, the Doctor’s going to die on April 22, 2011, but a new paper in the episode (detailing Nina’s emotional journey after getting kicked off Britain’s Got Talent) is dated 19 April 2011. So Amy and Rory in this episode have looped around back before they started on this season’s adventures. Which is why Amy’s drinking on the night of 22 April 2011 in The Wedding, because she knows that’s the Doctor’s death. So there are actually two Amy Ponds running around Earth in this episode. Yeah, timey-wimey.

That might be a bit weak, but not to fear, because Amy’s right back at it in The Wedding of River Song. It’s a great scene. She walks in on the Doctor and Winston Churchill, calls herself “Pond, Amelia Pond,” as if she were an MI6 agent codenamed 007 (7 is the number on her “room” in The God Complex) and promptly shoots the Doctor in the head. Yes, shoots him in the head. It’s a beautiful moment. In part because it’s just a stun-gun, ‘cause Amy wouldn’t really shoot the Doctor in the head for being an arsehole, unless it was with a water pistol (like in The Wardrobe, though to be fair she had it to ward off Christmas carolers).

That might be a bit weak, but not to fear, because Amy’s right back at it in The Wedding of River Song. It’s a great scene. She walks in on the Doctor and Winston Churchill, calls herself “Pond, Amelia Pond,” as if she were an MI6 agent codenamed 007 (7 is the number on her “room” in The God Complex) and promptly shoots the Doctor in the head. Yes, shoots him in the head. It’s a beautiful moment. In part because it’s just a stun-gun, ‘cause Amy wouldn’t really shoot the Doctor in the head for being an arsehole, unless it was with a water pistol (like in The Wardrobe, though to be fair she had it to ward off Christmas carolers).

But the other interesting thing about this shot is the costuming. Again, she’s wearing the black suit, and coupled with the eyepatch she’s totally rocking the aesthetic of the Silents. And eventually we see everyone wearing eyepatches. There’s a handwavey plot element to this, but seriously, everyone’s wearing eyepatches like they’re all pirates or something. Back in The Inferno, a Third Doctor story from like 1970 or something, wearing an eyepatch in an alternate universe was a mark of being evil or something. Anyways. Amy finished off her season’s arc by letting Madame Kovarian get tortured by her own electrified eyepatch, by making sure it’s properly affixed.

But this is not the end of Amy’s monstering arc. No indeedy. In Asylum of the Daleks we get a couple of interesting juxtapositions. First, and most obvious, there’s the fact that Amy gets infected by the Dalek Cloud, a bunch of nanobots that threaten to turn her into a Dalek puppet. In a particularly hallucinatory scene, she wanders into a room filled with Daleks, and declares them to be people – indeed, she literally sees them as people. Interestingly, they seem to see her as one of them as well. Well, insofar as we can believe the unreliable narration of the shots which are ostensibly from her interior first-person perspective, where one of the “people” looks at her and nods welcomingly. Here, the insanity of the Daleks is that they believe they’re people, an insanity Amy momentarily shares (and which of course foreshadows the reveal of Oswin). This is ultimately a character beat for Amy – she’s angry and bitter about not being able to have kids, which is Rory’s ultimate dream.

But there’s another “monstering” of Amy that’s far more interesting, I think. This time, rather than likening Amy to a monster, a monster is likened to her: the redheaded woman, Darla. Just being a tall ginge creates a visual likeness.

But there’s another “monstering” of Amy that’s far more interesting, I think. This time, rather than likening Amy to a monster, a monster is likened to her: the redheaded woman, Darla. Just being a tall ginge creates a visual likeness.

DOCTOR: Do you remember who you were before they emptied you out and turned you into their puppet?

DARLA: My memories are only reactivated if they are required to facilitate cover or disguise.

DOCTOR: You had a daughter.

DARLA: I know. I’ve read my file.

And the thing is, Darla had a daughter. Just like Amy. And Darla is quite cold about this fact, showing no emotion whatsoever. This, I should point out, was the center of much critique in the back half of Series Six, as people complained that Amy seemed to lack much emotion at all for the loss of her daughter.

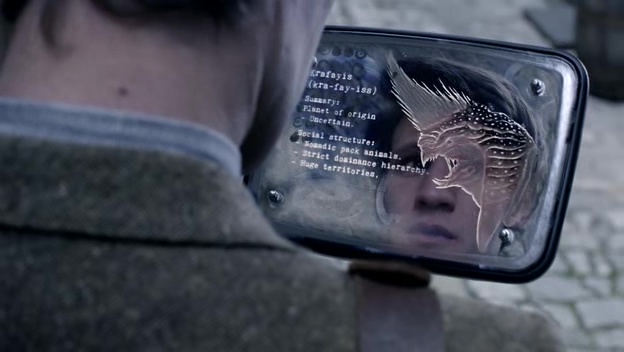

Not all monsterings are monstrous, though. In Dinosaurs on a Spaceship, we get a very interesting sequence where Amy is at perhaps her most Doctorish – she’s got her own companions, she’s investigating this mysterious ship, starts pushing buttons at a computer console… and it starts to fire up. But she’s not getting a picture, just static. We switch to a POV just behind the computer screen, such that Amy, Nefertiti, and Riddell are looking right into the camera. Amy begs the computer screen to give her a picture, and when that fails, she resorts to violence, giving it a good whack, much like the Doctors have done so (going all the back into the Classic era).

An image of a Silurian scientist appears on the screen, superimposed over Amy’s face. This is classic monstering, and to top it all off, Nefertiti points at the monster and says “Oh, it’s beautiful!” Now, I think this is great, and says more about Amy’s development than the implied critique of her violence. See, this is Amy being intellectual, figuring out the mystery of the dinosaurs on a spaceship, or at least the backstory of the mystery. She isn’t just juxtaposed with a monster, she’s juxtaposed with a scientist and savior. She’s also juxtaposed with Queen Nefertiti: Amy says that she is, indeed, a queen, and ends up taking command of this away mission. And when it comes to shooting dinosaurs, she’s juxtaposed with the big-game hunter Riddell. These juxtapositions are obviously carefully chosen. The other thing that’s clever here is that this particular kind of shot puts *us* on the other side of that television glass. When Nefertiti points, she’s pointing at us — making us beautiful monsters in the process.

However, if there’s one monstering that I’d call “gratuitous,” it’d have to be The Power of Three. In this episode, when the Cubes start coming to life, each one is different, unique, after being completely identical for nearly a year. One flies around shooting at the Doctor. Rory’s plays games with him, sliding open a door on whatever side is opposite him. Brian’s merely shifts position. And in the UNIT headquarters Kate confirms that they’re all behaving individually, from creating mood swings to playing the Birdie Song. Now, the Cube that Amy interacts with sends out a field of sharp pins, poking her in the hand, and on its side we see a pulse. As it turns out, this is the information the Cubes needed to create a mass heart-attack event. So this is a monstering.

But what does this have to do with Amy in this episode? Sure, she reacts and uses a defibrillator to restart one of the Doctor’s hearts, but is Amy being heartless at all in this episode? I don’t think so. If anything she’s milder than usual. A bit torn up about trying to balance her domestic life and her traveling life, sure, and there’s the whole “seared onto my hearts” speech by the Doctor, but it’s not like Amy’s actually being monstrous in these scenes or, indeed, in the whole episode. And neither is Rory, who is also monstered by virtue of the “nurse monsters” with cubic mouths. We might even say the Doctor is monstered in juxtaposition to the Shakri (coming from his own Gallifreyan mythology) but if anything what all these monsterings demonstrate is that they’re completely on the other side of the looking glass when it comes to our heroes – they provide contrast, nothing more.

Or maybe the Cubes find Amy’s heart because Karen Gillen was heartbroken during the filming of this episode, given she was leaving the show and her very good friends Arthur Darvill and Matt Smith. A bit of “meta” then. Funny thing, even after she left, Amy Pond still got monstered – in The Snowmen. Because the Ice Governess (who is cold to children) emerges from a frozen pond. But this isn’t nearly as exquisite as Amy’s monstering in The Angels Take Manhattan. Here, her image is replaced by the image of an Angel, which has sent her back in time, away from the Doctor. The Angel has taken Amy away from him.  But take it from her perspective. “When the Angel of Death approaches, he is terrible. When he reaches you, it is bliss.” For Amy, the Angel is no longer a monster, but something divine, for it reunites her with Rory. At the same time, it was Amy’s choice. So in a very real sense, Amy was the angel that took herself away from the Doctor. And then she “fixes” it (in the sense of making it permanent) by convincing the Doctor to complete a time loop back to her origin story.

But take it from her perspective. “When the Angel of Death approaches, he is terrible. When he reaches you, it is bliss.” For Amy, the Angel is no longer a monster, but something divine, for it reunites her with Rory. At the same time, it was Amy’s choice. So in a very real sense, Amy was the angel that took herself away from the Doctor. And then she “fixes” it (in the sense of making it permanent) by convincing the Doctor to complete a time loop back to her origin story.

Which brings us to Time of the Doctor, and the image at the beginning of this essay, just before the Eleventh Doctor regenerates. Here, Amy is kind of a Weeping Angel in her own right. I mean, she’s an “angel” in the sense that she’s only there in spirit. And her presence certainly marks the moment this Doctor is taken away, not just from Clara, but from all his fans. Most of whom, like me, were weeping during this scene, as they cup each other’s faces as they’ve been so wont to do.

This how you make monsters beautiful.

June 22, 2016 @ 11:36 am

I just wanted to say thank you for another thoughtful and though provoking piece. And I couldn’t believe no one had commented. So… thanks.

I look forward to more.

June 22, 2016 @ 12:58 pm

thanks!

June 22, 2016 @ 3:24 pm

Also thanks from me Jane. Another fascinating reading. Regarding this –

Back in The Inferno, a Third Doctor story from like 1970 or something, wearing an eyepatch in an alternate universe was a mark of being evil or something.

Indeed it was but I believe the eyepatch thing in Wedding of River Song was a cheekier bit of meta for old time fans. Back in the early days of Doctor Who conventions one of the stock anecdotes regularly reeled out to the delight of fans was Nicholas Courtney’s tale of being pranked on set while filming Inferno. His character, the Brigadier, did indeed have an alternate universe evil duplicate – the Brigade Leader, complete with eyepatch. Apparently Pertwee, after a break for lunch, arranged for the whole cast to be wearing eyepatches on set when Courtney returned. I suspect this was in Moffat’s mind when he created the ‘everyone’s wearing eyepatches now’ scene.

June 23, 2016 @ 2:12 am

This piece did the impossible. It made me consider rewatching Series Six sometime in the near future. Very compelling, very well argued. 🙂

June 23, 2016 @ 3:08 am

I enjoy this era more through your eyes than actually watching it. A bit like Mr. Marsfelder and Deep Space 9 magazine.

August 11, 2018 @ 8:27 am

A really very beautiful article Jane – thank you.