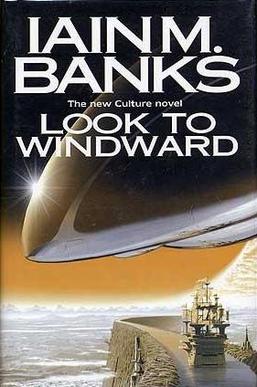

Cultural Marxism 7: Look to Windward

Banks published the Culture novels in essentially three chunks during which he’d write one every other year and between which he basically didn’t touch the setting. The first, consisting of everything through Use of Weapons, is dominated by already drafted material that Banks wrote prior to The Wasp Factory, and consists of Banks establishing the Culture in all its glories and problems. The second, beginning with Excession, but aesthetically encompassing The State of the Art, sees him testing the limits of the concept, pushing it to various breaking points to expose new faces of the idea. And it reaches its conclusion with Look to Windward. Whereas Excession and Inversions tested the limits of the format with massive high concept ideas like “what if the Culture met a vastly technologically superior civilization” or “what if you took the Culture out of a Cuture novel,” however, Look to Windward opts to break a far subtler rule: it’s a sequel to a previous book.

Banks published the Culture novels in essentially three chunks during which he’d write one every other year and between which he basically didn’t touch the setting. The first, consisting of everything through Use of Weapons, is dominated by already drafted material that Banks wrote prior to The Wasp Factory, and consists of Banks establishing the Culture in all its glories and problems. The second, beginning with Excession, but aesthetically encompassing The State of the Art, sees him testing the limits of the concept, pushing it to various breaking points to expose new faces of the idea. And it reaches its conclusion with Look to Windward. Whereas Excession and Inversions tested the limits of the format with massive high concept ideas like “what if the Culture met a vastly technologically superior civilization” or “what if you took the Culture out of a Cuture novel,” however, Look to Windward opts to break a far subtler rule: it’s a sequel to a previous book.

The clue’s in the title, which is a quote from T.S. Eliot’s “The Wasteland”—”O you who turn the wheel and look to windward.” The next line? “Consider Phlebas, who was once handsome and tall as you.” But Look to Windward is not a sequel to Consider Phlebas in any straightforward sense whereby it shares characters or even particular incidents. It is not the story of Bora Horza Gobuchul’s previously unknown child wrecking bloody revenge upon the Culture. It is not even another book set during the Idiran War. The War hangs over things, but only distantly: the novel is set in a period between the time the light of two supernovas becomes visible on a particular Culture orbital, the supernovas having been the result of the Idirans destroying two stars in the now eight hundred years past war. The Mind of the orbital is a veteran of the war, but this detail only becomes important (and indeed prominent) in the book’s denouement.

The seeds of shutting the whole Culture apparatus down for another eight years, in other words, are clearly visible. This is a book that’s straining against its own desire for straining, and it carries the sense of exhaustion you’d expect from that. And yet, ironically, this is also the reimagining of what a Culture novel can be that actually takes. From this point on, when Banks writes a Culture novel the act consists of simply writing a Culture novel as opposed to making some fundamental case for what it means to write a Culture novel.

In this regard, at least, it is fitting that the novel should serve as a sequel to the first Culture novel. Because make no mistake, it is a sequel to Consider Phlebas. The title doesn’t lie, and the Idrian war is too central to the book to be ignored, even if it’s too peripheral to call the focus. Like Consider Phlebas, Look to Windward is a book about war, a topic that, while certainly present in the other Culture books, is not generally their subject.

Though actually, its very presence is a bit odd. The Culture, after all, is an expressly utopian project. It’s not a given that futuristic utopias are pacifist—Star Trek notably isn’t—but there’s a certain obvious gravity towards it. But Banks did not just reject this angle, he explicitly chose to introduce the Culture at war. More to the point, he depicts the Culture in a war of aggression—one they started. That they did so out of moral principle, because the Idrians were actually evil, is an interesting detail of this, but it remains the case that Banks made a very deliberate choice to ensure that serpent remained in his garden.

This is not, clearly, out of some sense of fondness for the endeavor. While Banks may think war is inevitable, and cannot be excised even from utopia, this is not because of the necessity of it. The overall point of Consider Phlebas is the ugly futility of all its brutality, with its best aspect being the epilogue where Banks contextualizes the book in the larger war, mainly by suggesting the utter irrelevance of its events to the larger picture (which is itself a minor if “singularly interesting” conflict). Banks may have accepted the moral logic of intervention that underpinned the Culture’s decision to go to war, but war is treated more as an ugly consequence of that logic than as a valid alternate means of politics.

This is particularly visible in the war that Look to Windward focuses on, which is a civil war among another species, the Chelgrians, that kicked off because of a Culture intervention gone wrong. This is not because of a tangible mistake on the Culture’s part or anything; they did their usual thing of providing covert backing to oppressed segments of the population in pursuing political reform, and it just went terribly wrong when the chosen figurehead proved an unstable brute. War, in other words, is not something the Culture pursues so much as a reluctantly accepted occasional consequence of their interventions. This doesn’t entirely square away with previous books, where they definitely deliberately provoke wars, but it’s still clearly the context here.

But the Chelgrian civil war has also already ended when the novel starts, with only its prologue actually set during the war. Indeed, another way to frame its sequel satus Consider Phlebas is about the stupid brutality of war, whereas Look to Windward is about its aftermath. Look to Windward is dedicated to the Gulf War veterans, a dedication that, in the context of the 2000 publication date, points to the emerging recognition of Gulf War syndrome. This is a book about the traumas of war—the way its damage is experienced not just in the immediate circumstances of its destructive folly but over the long run, in old wounds that do not heal.

The central figure in this is Major Quilan, a Chelgrian who lost his wife during the civil war and who is now afflicted with a suicidal despair, which his government seeks to channel into a suicide mission against the Culture whereby Quilan will murder a Culture orbital in retribution. The novel essentially alternates between chapters from Quilan’s perspective as he gradually remembers the details of his mission (which have been temporarily erased from his mind in case the Culture scans it) and ones about life on the orbital, building to the moment Quilan’s plot is to go off.

This means, in practice, that the novel is a lot of waiting for things to happen. There’s not so much a plot as the gradual revelation of what Quilan’s mission is and then, once that becomes clear, a tension over how it will play out. But it’s not a procedural or a thriller—the alternating back and forth does not provide some cat and mouse game about the efforts to catch Quilan. It’s just a waiting game as the moment of decision ticks closer. There are other plot threads—an extended one about a Chelgrian expat composer on the orbital who is debuting a new symphony the first performance of which is where Quilan’s attack is set to happen—but it’s not a plot that’s long on events. It’s a meandering novel—the most “literary” that Banks has penned with an M in his name. That’s a desperately hollow aesthetic distinction, but it still stands in marked contrast to the (overly) frenetic pulp adventure of Consider Phlebas, and indeed even from the more ostentatiously stylish Use of Weapons.

What is the lasting damage of war, then? The obvious wrong answer is death. Death is what happens within war and its big tragedy, yes, but it’s clearly not what’s going on in the contemplative silence of Look to Windward. Nor is this some drab meditation on the cyclic nature of violence. Quilan’s attack fails comprehensively. The cycle of violence isn’t quite broken—Banks finds time for the Culture’s brutal and deterring retaliation against the Chelgrians—but it’s clearly not the point of the exercise. No, the word we’re looking for is mourning. What permeates the stillness of Look to Windward is a sense of grief, and a sense of despair at the permanence of grief. Both Quilan and, it ultimately emerges, the Mind he’s been sent to kill are haunted by what they lost during their respective wars and unable to move on from this.

And the novel ultimately rejects the possibility of moving on. That’s what giving the Mind a similar sense of mourning serves to do—establish that eight hundred years and a vast level of cosmic awareness that borders on omniscience is insufficient to resolve grief and heal the wound. What ultimately stops Quilan’s attack is a moment of empathy between him and the Mind in which they decide, mutually, to die themselves. The only hedge against this being an ending of outright bleak despair is the underlying sense of poetic beauty.

But what’s interesting about it is the sort of death that’s offered—one defined specifically in terms of oblivion and non-existence. Because that’s pointedly not the only sort of death on offer. Considerable effort is spent establishing the Chelgrians’ peculiar relationship with death, namely that they have an empirically verified afterlife by dint of having partially sublimed as a species. Quilan’s wife was specifically denied this afterlife for handwaved sci-fi reasons, and Quilan actively wants to avoid it himself, desiring actual un-being.

But this detail is interesting not so much because it changes the moral point of the book (which is a delicate enough thing to defy encapsulation) as because of the ways in which it points forward. When Banks picked up the Culture again after an eight year gap, questions of the afterlife would continue to intrigue him, with two of the final three novels working with ideas along these lines. Much as The State of the Art prefigured the second phase of Culture books’ approach, Look to Windward begins to show what the Culture will be like as Banks enters his de facto late style period.

In this regard, then, it’s worth stressing that Look to Windward is good in ways that the series as a whole has not been since Use of Weapons. None of Banks’s series-breaking ideas were entirely successful, though all had their charms. But Look to Windward is a deft and accomplished novel, its parts defly tallying to more than their sum without ever tipping into ostentation. There are odd details that jar—a subplot about an attempt to warn the Culture of the plot that never quite gets around to connecting to anything and resolves perfunctorily, and an epilogue that can fairly be called one clever twist too many—but even these seem proportionate to the whole, their frustrations no more than are appropriate for the book’s themes. It feels like an author who’s getting tired of his current approaches, but also of one who’s successfully refining them.

April 4, 2018 @ 6:45 pm

This isn’t the best book to discuss it since, from memory, I don’t think it’s even particularly mentioned but in light of my own personal transness and your own, I’ve been turning over an essay about the Culture novels and gender, given the interesting feature of the Culture that most members can change genders at will.

The part about this I most turn over in my head is Ian M Banks’ stated rationale for having it as a feature of his utopia, namely that the only way to ensure equal treatment of genders is to make it trivial society-wide to swap between them.

If I wrote it up I’d call it “The Transexual Culture”, a la Raymond…

April 4, 2018 @ 10:44 pm

It’s an interesting topic, though in one sense I feel there’s less there than meets the eye. I do Have Views on Banks’s treatment of gender and sexuaiity in the Culture books, but they’re a little carping, it’s hardly my area of expertise in any sense, and anyone who has just reached this point on the comment thread is about to discover just how little need they have to hear more from me at this time.

April 4, 2018 @ 9:50 pm

[I am afraid that, in the tradition of the Cultural Marxism series, this is one of my only-slightly-shorter-than-the-original-article comments. Skip to the end…]

I agree about the third-phase books moving away from the approach of testing the boundaries of the Culture novel, but as I see it the shift was not back to writing straight Culture novels, but rather to not writing Culture novels at all. You called Use of Weapons the last Culture novel, in the sense of being the last one formed by what Banks originally created the Culture to do, and I think this is the last Culture novel in a fuller sense. The third-phase books are merely novels with the Culture in them (albeit in them a lot), rather than novels about the Culture.

That’s partly a matter of plot: in all the stories up to this point, the impetus of events originates with Culture intervention policy, internal disputes over that policy and/or the reaction of other groups to that policy. In the third phase, the drive comes from non-Culture people pursuing aims unrelated to the Culture. I think the only exception to that is the GFCF in Surface Detail, and even they are only one part of a wider coalition, which is itself not the only major source of impetus in that book. The Culture’s involvement in the plot of each of those books is some mixture of investigation, extemporised reaction, and refusal to act. The shift also operates on the thematic level, where the things Banks is interested in are no longer explored through aspects of the Culture’s nature but concepts essentially unrelated to it.

Indeed, if I remember rightly, during the eight-year gap between the publication of this book and Matter, he more than once said that he was pretty much done with the Culture, and that perhaps the only thing left to do was a book about how it got started. In the event we got three more books, none of which were that, though The Hydrogen Sonata tantalised us with the suggestion that it might be.

I also disagree about the nature of the boundary being tested here. There would be nothing particularly un-Culture-like about writing a sequel, and Banks had arguably already come closer to doing so with ‘The State of the Art’, whose reuse of characters from Use of Weapons made it a sort of prequel (in the main narrative) or sequel (in the framing device). And outside of the Culture series, I don’t think he ever wrote anything resembling a sequel, so the tendency not to do so seems more an aspect of his writing in general than of that series in particular.

I do think the boundaries are being tested in other ways though. One of these is to ask the question ‘What if the Culture totally fucked up?’ It does seem that they made mistakes that contributed to the disaster. There is an element of chance contingency in the President’s sudden change of behaviour, but it is emphasised that the war snowballed with a speed and intensity indicating that he was not a freakish outlier, and it is explicitly suggested that the Culture’s grasp of Chelgrian psychology was less than perfect.

Earlier books emphasised the precision-engineered virtuosity of the Minds’ analysis and manipulation of other societies. That forms a basic prop of the Culture’s claim to the right to interfere, freeing their actions from a basic practical, and consequently moral, objection to ‘humanitarian interventions’ in the real world: the fact that in the face of the sheer complexity of human social dynamics, they have a very strong tendency to go badly wrong. (Aside: as reflected in that dedication, this book already felt closer than any of the rest to the real-world events of its time when first published, quite apart from the way that the next year’s events magnified the resonance of a book about a mass-casualty terrorist suicide attack against a superpower, a manifestation of ‘blowback’ arising from the repercussions of its bloodily miscalculated imperial foreign policy intersecting with religious militancy.) An intervention screwing the pooch on a gigadeath scale undermines confidence that Contact basically know what they’re doing, and thus challenges the moral logic underpinning the interventions which are the basic material of all Culture books, at least up until this point.

Arguably, that challenge had a lasting impact on the way the series was written, given the removal of proactive Contact intervention as a plot-driving force in subsequent books, which was reflected diegetically in an increased tendency for the Culture, or elements of it, to display diffidence about such intervention. Admittedly, this inclination is always opposed by other Culture elements in those stories, with whom Banks’s sympathy generally seems to lie, while any general shift towards restraint is presented as part of a recurrent waxing and waning of assertiveness rather than an enduring change in approach.

On a more immediate in-story level, the way the challenge is answered amounts to a reassertion of a principle from Consider Phlebas: the unsparingly, mathematically utilitarian nature of the Culture’s morality. In that earlier book the Culture justified starting, and unwaveringly pursuing to a finish, a war that killed hundreds of billions, by the calculation that the Idirans would have killed and otherwise harmed even more people if left unchecked for a few more centuries. Here, very apologetically but firmly chalking the Chelgrian fiasco up to experience and carrying on as before is justified on the grounds that the vast majority of Contact interventions work out successfully, and their benefits outweigh the cost of bringing about the occasional catastrophe. The same cold calculation underpins the merciless willingness of ‘the nice people’ (copyright C. Zakalwe) to torture people to death to make a point, just so long as the number of lives potentially at risk in the other side of the scale is large enough. The two books concerning the Idiran War may take their titles from The Waste Land, but they could have gone with The Shield of Achilles: ‘Out of the air, a voice without a face / Proved by statistics that some cause was just’.

The second boundary-pusher I would identify is ‘Can I tell a story that resolves inside the Culture?’ As Banks often observed, life in a utopia is generally too safe and stable to offer much in the way of narrative excitement, so his stories operate at the ragged edge of Culture intervention in other societies, where the requisite danger and high stakes are to be found. In other books, episodes inside the Culture tend to be merely preparatory set-up for the more adventurous activities that follow. Here, the serene heart of Culture society is not only a major setting but the place where the drama builds to its denouement. The introduction of uncharacteristic jeopardy to that setting is key to making that feasible, the underlying tension spicing the leisured debates and amiable banter of the sections set on the Orbital. In the end that air of suspense turns out to have been effectively illusory, the threat having been detected and countered in advance (it is not in fact Quilan’s heart-to-heart with the Hub that stops the attack, and I think that’s important – there is a kind of grace to their encounter that would be lost if it produced some material benefit). This storytelling device of using confected jeopardy to liven up the safe mildness of utopia has its counterpart within the story in the fondness of Masaq’’s inhabitants for dangerous extreme sports, and Ziller and Kabe’s discussion of what this sort of thing says about the utopian life.

Perhaps a third push at the boundaries of the series, though a less challenging one, is the inversion of the usual pattern of intervention in other societies by SC operatives, presenting instead a covert intervention within the Culture by operatives from elsewhere (give or take the unresolved degree to which all this is actually more of a self-reflexive intervention).

[Insert here last paragraph, which should be a good bit and have Skaffen-Amtiskaw in it.]

April 16, 2018 @ 10:00 am

Also how did I manage to talk about quasi-sequels and not mention States of War? Tsk.

April 4, 2018 @ 10:30 pm

On futility in Consider Phlebas, it’s interesting that the real degree of significance of the story’s events is left deliberately vague. The Culture estimate that if the Idirans were to capture the Mind, “it could lengthen the proceedings by a handful of months”, which, taking an average from the figures in the historical appendix, could mean something in the range of ten billion more deaths, so far from trivial in absolute terms, even if falling short of the customary conflict-deciding standards of the one-off epic. However, for one thing, even that calculation is predicated on “Assuming that we are going to win the war”. For another, the story is set shortly before the Homomda join the war, a momentous change in the course of events – we are told that the Culture had expected that this would not happen, and that ‘calculations concerning the war’s duration, costs and benefits had been made on this assumption’. That makes the estimate of the mission’s potential impact completely unreliable. What we don’t know is whether the changed context makes the outcome more or less important, or does not really affect it much at all. Given the general mood of the book, less would seem more likely, but we can’t actually be sure.

April 4, 2018 @ 11:23 pm

Although I love the Culture as a concept, the first Banks novel I read — Remember Phlebas — seemed so dreary and squalid, and its characters so unlikeable, that it was the only one. I wrote about my encounter with it here:

https://teaearlgreyhotblog.wordpress.com/2014/01/09/iain-m-banks-the-culture/

April 5, 2018 @ 5:51 pm

Read this one! Consider Phlebas is structurally and tonally quite different from the rest, being as it was Banks’ first published sci fi novel. It relies much more heavily on violence and its attendant plot settings and plot devices than any of the other Culture books, and Windward in particular.

April 5, 2018 @ 12:44 pm

Hi El. I love the Cultural Marxism series, and often wonder why it’s often quite sporadically set-up, without a single page to access them all through, and using a few different tags.

I appreciate this must be fairly low on your priorities, and I don’t want to be a typo-hunter (apologies if this is coming off this way), but would there be a way to make them easier to collect together without having to search around?

Again, apologies if I’m just being rude.

April 5, 2018 @ 1:02 pm

Stick “cultural” into the search box and they’re the top seven results.

April 5, 2018 @ 1:51 pm

Thanks. In hindsight, I was forgetting to put quotation marks around Use of Weapons.

So, really I was just not paying attention.

April 5, 2018 @ 1:08 pm

They should all be under the Cultural Marxism tag now. I’m unlikely to give them a place on the main title bar, though who knows how my blog series will be arranged in the Site Revision To Come.

April 5, 2018 @ 1:30 pm

the Site Revision To Come

“Watch this space, you poor doomed motherfuckers”?

April 5, 2018 @ 1:32 pm

[Still unsure whether that comment was the right pick over “I wish you good fortune in the site revision to come”.]

April 5, 2018 @ 1:52 pm

Thanks.

This is all starting to sound rather exciting.

August 8, 2018 @ 11:48 pm

Look to Windward is essentially a remake (deliberate, I would guess, though I’m not absolutely sure) of The Emerald City of Oz:

“The main plot of Emerald City concerns a plan by foreign hostiles to invade Oz and enslave and/or destroy its inhabitants, out of revenge for a previous intervention on Oz’s part; the story cuts back and forth between the antagonists’ gradual accumulation of forces, and the protagonists’ blithely wandering around Oz having adventures with no awareness of their peril. But in fact Ozma has all along been magically, if somewhat absent-mindedly, monitoring the invasion plans in her spare time, and when the enemy army arrives it is quickly and somewhat anticlimactically dispatched with the help of some magic dust. This description, with minimal alteration, would summarise the plot of Look to Windward also; there’s even an ‘E-dust assassin’ to correspond to Ozma’s magic dust.”

http://yellowbrickmeatgarden.blogspot.com/#14f