It’s a Game! They’re Taking Me For a Ride! (Into the Dalek)

|

| WE ARE THE DALEKS. WE HAVE INTERIORITY. |

If you want any Eruditorum Press books that aren’t Neoreaction a Basilisk, they’ll be going off sale around 2:00 EST this afternoon. This means it’s your last chance ever to buy Guided by the Beauty of Their Weapons.

It’s August 30th, 2014. David Guetta and Sam Martin are at number one, with Taylor Swift, Magic, OneRepublic, Wankelmut, and Union J also charting. In the last week, Modern Family and Breaking Bad won at the Emmys, while Amazon purchased Twitc. Alex Salmond and Alistair Darling debated Scottish Independence, Douglas Carswell defected from the Tories to UKIP, and Kate Bush staged the first concert of her Before the Dawn series, marking her first live performance in thirty-five years.

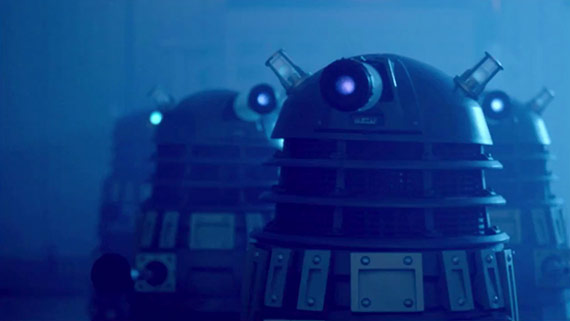

On television, meanwhile, Peter Capaldi climbs around inside a Dalek. On one level, this is another example of playing Capaldi’s rollout inordinately safe, going from a conservative Robot-inspired debut immediately to a Dalek story. On another, however, there’s a compulsive strangeness to this Dalek story. It’s based on what is clearly a kind of batty idea. Fantastic Voyage with Daleks is several miles from the sanest Doctor Who pitch ever. This is not necessarily a bad idea, of course. Some of the best Doctor Who stories ever come from completely insane pitches, and we all know what Series Eight story I’m thinking of here. But battiness is not a guarantee of success either, or else Daleks in Manhattan would be good.

More broadly, there is an element of “will this do?” to every Dalek story since about Doomsday. The answer to that question is often “yes,” and even sometimes “and then some,” but there’s still a niggling sense of “well we have to do Dalek stories occasionally so let’s see if we can come up with something” to them all. And Into the Dalek exhibits this more than most. It’s not fair to say that nobody was excited to see Phil Ford named as a writer for Series Eight, but those that were probably overestimated his contributions to The Waters of Mars and didn’t watch The Sarah Jane Adventures. Those who did recognized Ford as a writer who turns out unremarkable mediocrities with tedious repetitiveness, and his hiring as a clear and conscious lack of ambition for this story. The cynical way to frame it is that Ford is here to be rewritten by Moffat, a task he basically succeeds at.

Certainly anyone looking for reasons to slag off Into the Dalek is going to have a fairly easy time of it. Most of its best ideas were plagiarized from Rob Shearman. Nobody has actually come up with an interesting idea of what should be inside a Dalek, and the resulting set design is insipid. The CGI largely aspires to adequacy. But none of these are catastrophic problems. And while the same can be said of the stories’ virtues—none of them really manage to justify the whole—the story attains a sort of harmless mediocrity, neither particularly loveable or hateable. This will be something of a recurrent theme over the first half of Series Eight, which contains no egregious turkeys and exactly one classic, and is the clear downside of the extremely cautious rollout of Capaldi.

On the other hand, it’s hard to say that something like Into the Dalek wasn’t wise. Capaldi has his moments in the episode, though he understandably falters at the task of standing in front of a green screen and delivering lines like “Remember how you felt. you saw a star being born. The endless rebirth of the universe.” But there’s a strong sense of work in progress here. His opening TARDIS scene with Journey Blue is electrifying, and though it’s not quite the character Capaldi will eventually settle on, it feels confident and thoughtful. Elsewhere, however, Capaldi still feels slightly cowed by the part, still looking for the edges of it and at a point where his decisions are to try something instead of to do something. In that regard, the Daleks are playing much the same role as the Paternoster Gang, being a known quantity that can anchor things while the star keeps honing in on the part. (And of course Moffat did something quite similar with Matt Smith’s first two episodes, using River Song and the Weeping Angels to cover Smith’s work in progress performance; he just subsequently hid the story as episodes four and five of the season so that the audience was more familiar with the performance and would fill in the gaps left by the star’s inexperience.)

Another way of looking at this, then, is that Moffat is repeating the ploy of redoing a past Doctor’s debut story, this time redoing Power of the Daleks. In one sense this is the second time he’s done that, having already had Gatiss pilfer liberally from it in Victory of the Daleks. Though this comparison flatters Into the Dalek, however, it’s worth noting the inherent absurdity of giving Robot a luxurious seventy-five minutes and then trying to do Power of the Daleks in forty-five. What worked about Deep Breath was that it slowed down well beyond what was necessary, giving Capaldi and Coleman acres of space to work in, a decision that contrasted compellingly with the disposability of the actual concept. The best parts of Power of the Daleks, however, were always dependent on the fact that it was a 1960s six-parter that got to slow burn characterizations and revel in the strangeness of its concepts. Even though Into the Dalek comes nowhere near the hyperactivity of Series Seven Moffat, it’s still a big loud action story at heart. And that means all of what Whitaker did back in 1966 that this story has room for is the part that’s become a cliche—the sanctimonious Daleks who create moral equivalences. And the only way it has time to communicate that is in the most tedious way possible, with the Daleks attempting to create moral equivalences with the Doctor, and in the broadest terms, which is to say by nicking Rob Shearman’s climactic lines without any of the bleakly absurdist buildup that justified them.

Because let’s be clear here: that part of the episode generally pretty crap. The Doctor’s hatred of the Daleks, who are, let’s recall, genocidal nightmares who have previously attempted to literally destroy the entire universe, is in no way equivalent to the ideology that motivates mass genocide. The Doctor is, in fact, correct to define himself as not the Daleks, and the dramatic weight of telling him he is a good Dalek, even with then newly added double meaning of “good,” is fairly negligible. Likewise, all of the “am I a good man” business is criminally vapid. Clara’s “I don’t know” is preposterously unjustified (compare it to her unabashed hero worship of him next week), as, frankly, is the idea of the Doctor becoming consumed by the question in the first place. As a dramatic anchor for the story, it certainly drags it down.

Except there is more to this story than that: there’s Clara. Into the Dalek does not emphasize her revamping in the same way that Deep Breath did, but it still continues in the vein established by that story. Clara is given a measure of authority over the Doctor that’s unusual for a companion. It’s not that the joke of the companion being the Doctor’s carer wouldn’t have worked for plenty of other companions; it’s that relatively few of them would ever say it. And not only is Clara the Doctor’s carer, at various other points in the story she’s his teacher and therapist. All of these are roles with tacit power relationships, and the power relationships always flatter Clara. When people complain about this, they tend to suggest that this constituted making the show about Clara, but it’s hard to see why that would be a bad thing when you have Coleman and Capaldi immediately developing a chemistry to rival Piper and Tennant, Aldred and McCoy, or Manning and Pertwee. If the fact that in 2014, at fifty-one years of age, the show finally embraced the promise of an iconic double act by letting the female half of the equation actually have a starring role is a problem, well, the problem is you.

But this is also the story that introduces Danny Pink. Danny is not a presence here per se; he’s restricted to some light comic scenes that do not really give a sense of him as a character beyond the detail that he’s ex-military. But the story is still about him inasmuch as all of the bits he’s not in are about the Doctor’s complex relationship with the idea of soldiers. Well. I say complex. In practice, Into the Dalek has relatively little to say about this. dynamic. It’s just that what it has to say is generally satisfying, most particularly “you don’t need to be liked, you’ve got all the guns.” Equally, the Doctor doesn’t actually get to be right about any of this. His intolerance for soldiers is directly equated to his (morally condemned) hatred of the Daleks by juxtaposing his spurning of Journey Blue with the “you are a good Dalek” business. This doesn’t go anywhere, but more in the sense of aporia than fizzling out. It doesn’t quite justify the pathetic absurdity of trying to sell the Doctor and the Daleks as moral equivalents, but it is at least interesting in its own right, and more to the point it’s an idea the series will develop interestingly over the season. (Indeed, the more charitable reading of Ford’s partial authorship is that the soldier material was part of his season arc, and that he wanted to handle it, while the meat of the story was more straightforwardly Ford’s.)

Much of why this works is that unlike the Daleks, there actually is a moral complexity to soldiers, both in reality and in Doctor Who. On the one hand, they are acutely of the working class, subject to the capricious whims of authority. On the other hand, they are the direct enactors of the violence by which that authority is enforced and maintained. One can try to collapse this into a sort of “love the sinner, hate the sin” framework whereby one evinces sympathy and compassion for the individual soldier while remaining steadfast in opposition to the larger system they serve, but that kind of distinction collapses pathetically in the face of actual efforts to employ it in the real world. It’s murky and difficult, in the way that the interplay of individuals and systems often is. And it’s a murkiness that’s often appeared in Doctor Who between the Doctor’s tendency to find themself opposing alien armies (with the Daleks serving as the archetype of this) and their tendency to ally, with varying degrees of reluctance, with human military forces. So picking at that scab and having the Doctor be firmly situated in the murk is effective, or at least it would be if the whole thing weren’t rooted in the Daleks, i.e. the single least morally ambiguous soldiers in the entire series.

And yet the Daleks, all told, work here too. Sure, the actual interior of them is a bust, but this is the place where the decision to hire Ben Wheatley to direct pays off the best. Hiring an established and acclaimed film director to helm Capaldi’s first two episodes provided a stabilizing baseline. These episodes just plain looked good. The visual match between Journey waking up in the TARDIS after her death and Gretchen waking up in Heaven (in part the work of an uncredited Rachel Talalay, though she was working from Wheatley’s ideas) is a fantastic way of alluding to who Missy is. But the real triumph, as I suggested, is how good the Daleks look. The promise of explosive Dalek action has always been a double-edged sword for the series, simultaneously serving as the primary appeal of the concept and as a thing that the realities of BBC budgeting always leave partly out of reach of the program. But Wheatley sets a new high water mark, offering a deft play of light and color that is at once brutal and breathtaking. This feels like what Daleks always should have looked like, to an extent that just about justifies the naff bits promised by the actual title. (Indeed, part of why it works is precisely because it’s a climactic reward as opposed to something that’s sustained for forty-five minutes.)

So in the end we have a story with two strands, each of which is strong on its own merits (or at least competent), but where the connection between them lets down the whole. But as we said, this was never a story that aimed higher than that. Its purpose was to not be embarrassing while Capaldi progressed towards getting how to be the Doctor, and it cleared that bar handily. Will this do? Surprisingly well, actually.

April 2, 2018 @ 1:39 pm

“Ford’s Partial authorship?”

April 2, 2018 @ 1:44 pm

I was already aware of Wheatly before these two episodes, and I had seen Kill List on the recommendation of a YouTuber whose name I can’t recall. But these stories got me to watch his filmography, which I am eternally grateful for (now to get on with watching Tank Girl and The Wind in the Willows).

April 2, 2018 @ 1:45 pm

i.e. “why did Moffat, for the first time in his Doctor Who tenure, take a coauthor credit?”

April 2, 2018 @ 2:17 pm

Fair enough, I thought the “his tenure” in the parenthesis was referring to Ford.

April 8, 2018 @ 5:45 pm

Yeah, I came to comment that that parenthetical is unclear because the referent of “his” seems like it should be “Ford” but is actually “Moffat,” even though Moffat was last mentioned three paragraphs prior!

(Hi Sean!)

April 8, 2018 @ 5:55 pm

Now that I’ve read all of the comments, I would like to delete the above post, I guess.

April 9, 2018 @ 4:46 am

Corrections and queries about things that actually impede meaning do not bother me. Nitpicky spelling mistakes do.

April 2, 2018 @ 2:04 pm

On rewatch, I feel like this is the episode of Series 8 that has improved the most on rewatch. I think there’s a bit more going on under the surface, but I’ll spare anyone till I have the time to write a blog on it.

But even without that–as something you’d just want to pop in and watch on a Sunday afternoon, this really plays well. It’s darkly funny, the Dalek battles look stunning, Clara and 12 are popping, and the cinematography is super pretty.

As time goes on, there are a lot of episodes that fall out of the “Rewatch Repertoire” of eps that you just want to watch by themselves because they give you something that satisfies a mood. I don’t ever get the urge to rewatch “Victory of the Daleks” on it’s own, for instance. When going back to the old favorites, I never would have guessed I’d be coming back to this one? But here we are.

Also: I love rusty.

April 2, 2018 @ 2:13 pm

Yeah, my biggest issue with this episode is the set design. They didn’t have the budget to do what I see in my head as what the inside of a Dalek is like (and even if they did have the money, I doubt they’d have wanted to spend it on this episode), so all we get are some bland corridors and plastic tubes. There could have been Dalek tentacles and weirder antibodies than we got and who knows what else – turns out all that’s inside a Dalek is Doctor Who corridors, a few ducts, and some floating robots. This should have been the Claws of Axos for the Capaldi era, dang it!

April 3, 2018 @ 3:28 am

“…all that’s inside a Dalek is Doctor Who corridors”

I don’t know, somehow this seems perfectly correct to me. As above, so below.

April 3, 2018 @ 1:35 pm

It’s corridors all the way down!

April 2, 2018 @ 3:19 pm

Perhaps it is in the spirit of things to try an alchemically-inspired redemptive reading, where this episode puts forward the operation of “putrefaction”. I understand that this means a fundamental sort of transformation, where a substance decomposes and rots, and from that emerges a purified essence of a new material. This is made literal in the Dantean journey through the Dalek itself, especially the descent into its digestive parts, and the post-regeneration context. Moreover, on the moral plane, putrefaction is present in the Dalek’s self-destructive encounter with the numinous power of its own memory, as mirrored by the Doctor’s evolving self-understanding.

Of note here is that the human ship is called the Aristotle. This name could refer to all sorts of things, but in the realm of drama, there’s a particular notion associated with Aristotle of the ways in which stories work by purging the viewers’ emotions – a kind of purification or putrefaction.

The inevitable conclusion: this episode is an example of “the catharsis of spurious morality”.

April 3, 2018 @ 4:11 pm

I’d sooner refer to Aristotle’s metaphysics/ethics before his writings on drama. That might just be because I haven’t read the Poetics in years — but then, this is an episode about “being good”.

I like your point about putrefaction. I don’t want to plagiarise DoWntime’s brilliant analysis of this episode, but it’s worth noting the language — “Coal Hill”, “Journey”, “into darkness”, etc. You can almost feel a process of blackening, transforming, at work here.

April 12, 2018 @ 10:46 am

Really love these readings of framing the story with an alchemical context – the putrefaction, as above/ so below, and Cola Hill, etc. With the “Into darkness” trailer and the journey the Doctor seems to be taking within, THEN going within the Dalek – it all feels kind of perfect for helping in setting up a Doctor with a new regeneration cycle to go through a deeper sense of inner transmutation and journey of the soul.

I guess it doesn’t really matter if some of the visuals don’t match up with the ideas, as that has always been the charm of the show, and just like sets, CGI is not a guarantee.

April 2, 2018 @ 4:11 pm

Whilst the chemistry between Capaldi and Coleman is obvious, I’m just not a fan of the Clara character, and I don’t think she ever really quite worked.

On the subject of her essentially taking the ‘starring role’, I saw more people quibbling about how they hated it because she was poorly and inconsistently written, rather than because of her gender.

But admittedly I only really go into the er, ‘less excitable’ Dr Who forums. Having seen some of the extreme reaction to Whittaker’s casting, maybe I just wasn’t looking in the right places for the sexist takes on this episode…

April 3, 2018 @ 3:36 am

I mean, given that “poorly and inconsistently written” is just categorically untrue for Clara, there’s a fairly high chance that a lot of the problems people have with her stem from misogyny.

She demands attention and she really wants nothing more to be the centre of a mythic universe the size of Doctor Who’s. Those aren’t things female characters (or women, for that matter) are generally meant to do. As a character, she’s complex and contradictory, demanding attention, thought and compassion. She’s not easy – as a person or as a character – and women who are difficult are scorned.

However, if you put in the effort to understand her (and if you’re reading TE I can guess you like thinking about the television you watch), she’s the most infinitely rewarding character.

April 3, 2018 @ 8:37 am

I dunno, that sounds more like genuine confusion to me. There might be a danger of “ascribing to malice what can be adequately explained by incompetence” here.

Doctor Who has traditionally been a show whose leads are not terribly complex characters, but who are often terribly fun to travel the universe with. That makes a lot of sense for a show whose basic format is a magic thing which can go anywhere in time and space – it’s the “anywhere in time and space” which is the focus, not the people going there.

Hence it makes sense for a lot of fans of the show to be the sort of people who are good at or interested in understanding imaginary places, but who are not nearly so good at or interested in understanding imaginary people. And if you’re not up to difficult tasks of understanding imaginary people, then when presented with a complex character full of human contradictions, it takes a considerable amount of willingness to admit to your limitations not to be tempted to put those contradictions down to bad writing.

One thing in particular about understanding characters is that the difficulty of it varies massively depending on whether you’re similar to them or not. As someone who is similar to practically nobody in fiction or surrounding me in the physical world, (yay internet and its ability to massively increase the size of the pool of people you can try talking with,) traditional Doctor Who works well for me because the focus is on understanding things like social, political or philosophical topics, “people” in general, where this isn’t a huge disadvantage. Character complexity for its own sake, at least in live-action where you need to be able to read realistic body language, is not going to be a fruitful area of concentration for me.

April 3, 2018 @ 9:50 am

With regards to the “is Clara consistently characterised”? question, I would highly recommend the following series of articles by Ruth Long, which pick apart the themes of Clara’s time on the show in detail, and make a strong case that, yes, she is well characterised.

http://www.doctorwhotv.co.uk/clara-oswald-a-study-of-the-impossible-girl-78428.htm

http://www.doctorwhotv.co.uk/clara-oswald-a-study-of-the-impossible-mirror-78978.htm

http://www.doctorwhotv.co.uk/clara-oswald-a-study-of-the-impossible-storyteller-part-1-79998.htm

http://www.doctorwhotv.co.uk/clara-oswald-a-study-of-the-impossible-storyteller-part-2-80054.htm

http://www.doctorwhotv.co.uk/clara-oswald-a-study-of-the-impossible-storyteller-part-3-80103.htm

I am curious though – in what ways do you feel she was inconsistently written?

April 3, 2018 @ 10:11 am

As to misogyny, I’ve seen commenters calling her misognystic slurs, and wishing violent harm on the character, so yeah, I’d say there’s at least a touch of blatant misogyny there.

But I think sexism tends to manifest itself in subtler ways in criticisms of Clara – which is sort of the crux of Caitlin’s comment. Fans have blatant double standards for her that they don’t have for the Doctor – to keep this comment at less than an essay, I’ll focus on one key example:

In series 9, the Doctor gets a one off episode where he’s basically the only character in “Heaven Sent”, and a big ten minute speech at the end of “The Zygon Inversion”, as well as his usual mix of character development and big hero moments. Clara, meanwhile, basically doesn’t feature in two episodes, save for brief cameos (“The Woman Who Lived” and “Heaven Sent”).

Yet fans complain Clara “takes over the show” in the season: that’s one of the most common complaints about her departure from the show. There are studies that show men believe women who speak less than half of the time in a conversation are “dominating the conversation” – that may not be immediately obvious sexism, but it is sexism – sexism that comes from men feeling entitled to the undivided attention of women. And I think there’s a similar sexism that motivates criticisms of Clara’s character: there’s no metric by which she “takes over the show” in series nine (arguably, she gets less of the focus than a co lead should have). But she’s a female character who wants to be like the male lead, and whose story ends with her being shown as being capable of being like the male lead. That a group fans reacted so negatively to this ending, and would rather have seen her die as a consequence of her trying to be like the Doctor, does ultimately reek of sexism to me, even in the cases where no misogynistic slurs were thrown around.

April 3, 2018 @ 11:09 am

In contrast with my post a bit above, “takes over the show” is certainly a criticism it’s hard, if not impossible to explain without misogyny.

April 3, 2018 @ 3:34 pm

But Clara literally takes over, to the point where her eyes and name show up first in the title sequence for the finale, all for a cheap (not actually funny) joke.

April 4, 2018 @ 1:56 am

Counterpoint: that joke is rad and good.

April 4, 2018 @ 8:11 am

So, Clara’s eyes appear in one episode for a joke (which, as Reece says, is a rad and good joke), and you think this counts as evidence of her “taking over the show”?

Okay, just for context, let’s break this down a little more.

Number of episodes Capaldi and Coleman Appear in together: 25

Number of times Capaldi’s eyes are in the Credits: 24

Number of times Coleman’s eyes are in the Credits: 1, for a joke

April 4, 2018 @ 9:00 am

Correcting myself, Capaldi’s eyes appear in 23 title sequences, because of “Sleep no More”

April 4, 2018 @ 9:22 am

“Sleep No More” takes over the show!

April 4, 2018 @ 5:43 pm

For one episode, in a season that she had the most focus next to Twelve.

Now, if she and Capaldi had both of their eyes in the shot for ever episode….

that would be awesome and should be considered as an idea for the new era.

April 5, 2018 @ 2:29 am

“that would be awesome and should be considered as an idea for the new era.”

I would have thought that the new era is the one time this wouldn’t be quite such an awesome idea to introduce. But if they cast a male Doctor after Jodie Whittaker then yes, I’m with you, awesome.

April 3, 2018 @ 10:45 am

Setting aside the questions of sexism and whether Clara was consistently written, I think many people among the audience just don’t particularly like companions who step out of their designated role. Companions are consistently written as secondary to the Doctor and so when the show challenges that dynamic there are always complaints. I remember many people being upset about Rose and how she became this special companion/love interest/time goddess over the course of her two seasons. Which, to be fair, is sexist in itself but it’s a slightly different flavour of sexism than “I just don’t like powerful women”.

I also feel like Series 7 broke Clara irreparably for many viewers. When the Doctor treated her a mystery it was hard to just like her as a character – if he keeps her at arm’s lenght, why shouldn’t we? By the time she caught her second wind with Capaldi she was given the job of opposing the Doctor. That made her more interesting but again, harder to like. I’ve personally always liked her but I can easily see why she was a harder pill to swallow than Rose, Martha, Donna, Amy or Bill.

April 6, 2018 @ 9:47 pm

I’m aware of the sexism online regarding Clara – most female characters in every popular series ever in the Western world are subjected to it sooner or later (although some do get it a lot worse than others.) As far as I’m concerned, the heavily emphasised ‘mystery’ of who Clara is in series 7 is the main problem with her. So much is made of her mysteriousness that when we get to the point of The Doctor’s regeneration, it’s a little hard for her to anchor the story. We simply don’t know who she is. I think for a lot of viewers this is never really resolved. Personally, I would love a strongly drawn female companion who takes over The Doctor’s role where necessary – I just don’t think Clara is it.

Luckily there will be a chance to resolve this issue with a female Doctor. Who probably won’t get comments about ‘too-tight’ skirts made about her either…

April 6, 2018 @ 10:31 pm

So your issues with her first eight episodes ruin the other 27? That feels strained.

April 2, 2018 @ 4:42 pm

“Am I a good man?”, asks the Doctor. The word “good” acquires an interesting valence here: the Doctor is equated to a good Dalek, who’s still ruled by hatred – only it’s vector (like the polarity of the neutron flow) is reversed. Being “good” does not preclude you from comitting atrocities. (Like you say, the equivalence is a bit ridiculous, but in my opinion it’s kinda fitting with e.g. The Day of the Doctor.) And you can still be an ass to others; based on this episode, my reading of the Twelfth Doctor at this stage is that he is tired of doing what he does, hence being cranky and insulting, dispensing with basic politeness, but still feels obliged to save the universe. He tells himself that it’s okay, it doesn’t matter how he behaves, as long as he can be called “good”, as long he hates evil and fulfills the quota of good deeds. Still, the question seems to trouble him and maybe seeing himself reflected in Rusty starts him on a path of reflection that will lead him to formulating a new ethos for himself. We’ll see that development later in the series and in the following Capaldi seasons, of course.

“It’s not fair to say that nobody was excited to see Phil Ford named as a writer for Series Eight, but those that were probably overestimated his contributions to The Waters of Mars and didn’t watch The Sarah Jane Adventures” – I laughed at this sentence, because it describes my reaction to the news of Ford (co-)writing an episode with 100% accuracy (and no, I haven’t seen The Sarah Jane Adventures).

April 3, 2018 @ 10:53 am

The very fact that the Doctor starts to ask himself that question is a great indicator of just how lost this Doctor really is. He has lost his way to such a degree that he’s unsure whether he can still funfill his basic function.

April 3, 2018 @ 10:54 am

And that should read “fulfill”, of course. Although “funfill” is an interesting word.

April 3, 2018 @ 4:19 pm

Wasn’t Aristotle all about developing character through repetition? Emulating the virtuous, aiming for the good, working towards eudaimonia, until such behaviour becomes habit and you’ve got a good disposition too.

That fits with your reading, I think — with a new personality and new inclinations, the Doctor has to learn this all again. He has to practise. Thankfully he does have a teacher to emulate (and she literally states outright here that she’s still his teacher).

(If I’ve grossly misunderstood Aristotle here, do correct me. I’ve always been more of a Plato girl.)

April 4, 2018 @ 6:14 am

The Doctor was a big fan of Plato according to the David Whittaker version of “The Daleks”

April 2, 2018 @ 4:53 pm

I found that line near the end ‘the good Dalek’ to almost ruin the episode for me.

Despite that, this is one of the few Dalek’ stories that I like.

It’s not just the aspect of there being a ‘Good Dalek’ There has been good ones before in Doctor Who. It’s more of having a Dalek have a character to sympathize, when they also have their monster moments. Like Dalek’ Sec or the Dalek’ from Dalek.

I like Danny Pink. I wished he became a companion, or even gone on one trip, but he was a good man.

Have any of you find it interesting that Danny had a few minutes in this episode, setting up his character? We see him at the school, diving a bit from life as a solider, and having chemistry with Clara. In a span of a few minutes, all that information.

To me, the ‘am I a good man?’ arc was a breath of fresh air. And something that the show needed to showcase. When series 2 started, and Tennant jumped right into it, it always felt jarring (like a lot of series 2, both good and bad) And because I saw ‘Journey’s end’ and the specials afterwards, that might have colored my view on Ten.

From someone who became a fan of Capadi’s work from his announcement, I enjoyed the breathing room that he had to find himself.

In the story, the Doctor spent over 900 years protecting a small planet from being destoryed by fleet of monsters. At the least, it’s been a few days for the Doctor since he regenerated.

April 2, 2018 @ 4:59 pm

I like Danny Pink, too, and I’m interested to see how Elizabeth interprets him for season 8 almost more than anything else from the season (the post for Kill the Moon being my most anticipated post for this season, as it is for everyone else, probably).

April 3, 2018 @ 11:04 am

I’ve always had a problem with the Doctor being tired after defending Trenzalore for hundreds of years. It certainly makes sense and fits with Capaldi’s later performance but I find it very hard to relate to his experiences there. It’s just such a sci-fi idea, so far away from human concerns – and the fact that all of that character development happens ofscreen only adds to the problem for me. In the span of an hour of television the Eleventh Doctor goes from a character we love to a character we barely recognize. It’s hard to consider this one hour as important as three seasons of character development we actually got to see.

April 4, 2018 @ 7:16 am

Perhaps it’d be easier to understand in terms of how long he’s been doing what he does, his many losses and sacrifices throughout the years: ones that we’ve seen in the series as a whole. Doing good is not easy (the Twelfth Doctor says it explicitly in The Doctor Falls and it’s especially visible to me in the Davies/Gardner era, where every major victory comes at a cost of a major sacrifice: hence why every season finale comes with either a regeneration or a companion departure) and the Doctor has been doing good for a long, long time. Trenzalore is just a culmination of that and it’s quite easy seeing how Twelfth turned out, to retcon the Eleventh as wanting to die, being ready to die at the end of that adventure – but it turns out that he won’t, with a new regeneration cycle he’ll keep going who knows how long. And then, as Twelve, he eventually decides that no, screw that, I’m done.

April 4, 2018 @ 8:46 am

Okay, that helps, thank you.

I think part of my problem with the Eleven/Twelve personality change was the fact that “Time of the Doctor” happened just one episode after “Day of the Doctor” which was all about another big personality change. To see the Doctor go from finally recovering from the trauma of the Time War to being tired, spiky and unpleasant over the course of one story felt very jarring to me at the time. Perhaps I was just expecting a different Twelfth Doctor than the one Moffat had envisioned. Oh well. I warmed up to him eventually!

April 2, 2018 @ 10:12 pm

Just as a friendly pointer: it should be “the star keeps homing in on the part” not “the star keeps honing in on the part.”

April 2, 2018 @ 11:12 pm

Errors of this sort get corrected for the book version, and pointing them out here is both unnecessary and kinda annoying.

April 3, 2018 @ 5:20 am

Bloody hell El, he was just trying to help.

April 3, 2018 @ 2:18 pm

I got a PhD in English. I’ve been around enough grammarians to be well aware that comments consisting of nothing save for a pedantic correction are not in fact efforts to help, but rather smug demonstrations of superiority. If there’s an error that’s actually obscuring meaning, by all means point it out. That’s helpful. If literally your only insight about a 2000 word essay is “you made a typo” then you’re just being an asshole.

April 12, 2018 @ 5:16 am

Spoken like a true neurotypical.

April 12, 2018 @ 7:26 pm

I mean, OP proceeded to launch a massive spam attack while gloating about “triggering” me that resulted in us having to shut down comments for an hour and issue our first ever IP ban against someone, so this may not be the greatest of hills to die on.

I also bristle a bit at being called neurotypical. I strongly suspect I could get a diagnosis of being on the autism spectrum if I wanted such a thing, but I have no interest in being pathologized in that regard, and in the absence of such a diagnosis pointedly decline to identify either as neurotypical or neuroatypical.

April 3, 2018 @ 4:53 am

thank rất nhiều về bài viết của nhà sản xuất

April 3, 2018 @ 12:17 pm

Nah, I reckon in terms of Dalek action, Parting of the Ways has this beat.

Maybe because it was the first thing to fulfil that childhood wish of an army of Daleks, but I also think there is too much focus here on making the Daleks dynamic. There’s so much waggling and explosions as they move in roughly triangular blobs.

In Parting of the Ways they move with an arrogant patience; taking their time, never exterminating before they’re all in position. They’re the inevitability of death.

April 3, 2018 @ 12:18 pm

Interesting, as always. Thanks for a lot of things to think about.

I can’t remember if it was ever explicitly confirmed or denied but there was this persistent rumour that Doctor Who creators were legally bound to include the Daleks at least once per season of the new series if they wanted to keep using them. Regardless of whether that’s true, this rumour/explanation accurately describes how the Daleks are used in the Moffat era: for one-shots and cameos. Series 6 had only one short scene with a Dalek, didn’t it? They’re no longer play a central role in the show like they did in the Davies era.

It’s also interesting to consider your observation (made several times in regards to Classic Who) about how the Daleks validate the Doctor by recognizing him when they meet a given incarnation for the first time. Here at the very beginning we get a moment of false recognition with Rusty who turns out to be asking for a doctor, not the Doctor. But then the real recognition never really comes. The only Dalek the Doctor interacts with in this story is “broken” and doesn’t recognize him at all – which further drives home the parallel between them as they have both lost their basic narrative function. A Dalek that wants to destroy other Daleks. A Doctor who’s unsure if he’s a good man. Two broken characters trying to define themselves by contrasting themselves with the other. Like they did at the very beginning of Doctor Who.

What we get in the end is not the usual “the Doctor is not a Dalek” but a far stranger (albeit not very convincing) “the Doctor is a good Dalek”. When we first heard that line in “Dalek” it indicated that the Ninth Doctor is scarred by the trauma of the Time War and needs to heal before he can truly be the Doctor again (starting with not blowing up the eponymous Dalek in the climax of the episode). Here the line seems to point towards the Twelfth Doctor having forgotten that fighting evil does not automatically equal goodness. Without his trademark kindness (and he’s definitely not kind here, demanding politeness from a scared woman who has just lost her brother and lying to a dying soldier to pursue his own agenda) the Doctor turns into a monster-fighting machine, effective but cold and, frankly, quite terryfing. A “good Dalek” indeed.

It’s interesting that out of the whole Capaldi era it was Rusty the good Dalek who returned in “Twice Upon a Time” to bring that era to a close. In a way it’s very fitting: he represents this Doctor’s lowest point, a version of him that was considered and ultimately discarded in favour of a far warmer, kinder, less authoritarian one. As mediocre as this episode was, it was the beginning of the redemption arc for the Twelfth Doctor.

April 3, 2018 @ 4:03 pm

So… I’m not sure I agree with your reading that the Doctor is morally equated to the Daleks here. I do agree that this would be morally problematic, but I don’t think it’s what the episode is trying to say in its re-purposing (?) of Shearman’s quote. To say that the Doctor is “a good Dalek” isn’t to say that he’s good at being a Dalek, but that he thinks a bit like a Dalek…. but unlike a Dalek, he’s good.

It’s admittedly not the most ambitious message, nor is it that clearly conveyed — but I quite like it regardless. They’re less “moral equivalents” as you put it, and more “psychological equivalents”. Both the Doctor and the Daleks are defined by their absolute and unwavering dedication to a single cause: the Doctor hates the Daleks, and the Daleks hate everything else. I don’t think that’s any sort of moral slight on the Doctor’s character, and it shouldn’t be. He has every right to hate (and fight) the Daleks, and to define himself in opposition to them. But it’s a unique perspective on his psyche following an incarnation who couldn’t sit still and regularly changed his mind about everything and everyone.

If we were expected to condemn the Doctor following this judgement, I think Clara’s assessments of him would have to be reversed. She’d start the episode with certainty and end it with uncertainty (or outright condemnation). But she doesn’t — over the course of the episode she goes from “I don’t know if you’re a good man” to “you try your best, and that’s what counts”. She’s remarkably untroubled by learning that the Doctor is a “good Dalek” — so maybe that’s not such a bad thing to be after all.

This was another interesting read, anyway. You’re quickly becoming the highlight of my Tuesday afternoons. (I’m surprised that there’s no mention of Aristotle here anywhere, though, but there’s always the comments section for that.)

April 3, 2018 @ 8:42 pm

I’d also say that when he asks “Am I a good man?” the part of the question left implicit is not “compared to the Daleks.” It’s more a matter of how he stacks up to the soldiers he was willing to sacrifice to defeat the Daleks. It doesn’t entirely come off, but does give the viewer more to chew on.

April 3, 2018 @ 4:54 pm

Love that caption.