|

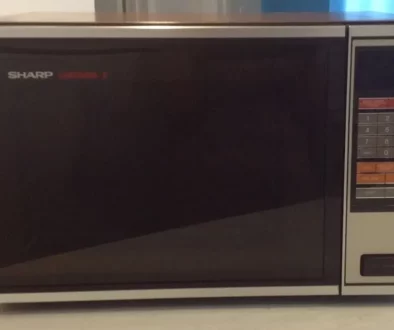

Figure 822: The revelation of obscene

alien graffiti, a plot point shared by

both Moore and Morrison. (Written by

Grant Morrison, art by Colin MacNeil, from

“Fair Exchange” in 2000 AD #514, 1987) |

There is no way to reasonably deny the fact that Morrison’s short pieces for 2000 AD owe a heavy debt to Alan Moore. “Hotel Harry Felix,” features an alien life form that takes the form of thoughts and ideas, a concept Moore had already explored in “Eureka.” His second, “The Alteration,” is a two-pager featuring a man on the run who is caught by monsters and turns into one, only to have it turn out that he was actually a monster who had contracted “humanitis” and was being cured, a joke not entirely dissimilar to Moore’s two-page “Return of the Thing.” His fourth, “Some People Never Listen,” bears more than a passing resemblance to Moore’s “The Bounty Hunters.” His seventh, “Wheels of Fury,” featuring an AI car that turns into a jealous lover, is almost a straight reworking of the Moore/Gibbons “The Dating Game,” in which a city’s central computer becomes a jealous lover. “Fair Exchange” uses the same joke that concludes “D.R. and Quinch Have Fun on Earth” of a comedic misunderstanding in which an alien is presented with something that is secretly rude graffiti in its native language, while the two-part “Fruitcake and Veg” is a more or less straightforward repeat of the basic joke of D.R. & Quinch, including a section where the narrator reflects, “People say to me, ‘Mr. Sweet, what is it that makes yo commit senseless and irresponsible acts of wanton destruction? What made you become the deranged homicidal maniac we’ve come to know and love? Well it’s a fair question. So I always give them a fair answer. I say it’s my upbringing, I tell them society’s to blame… and then I blow ‘em up!” And the similarities continue right up to Morrison’s final Future Shock, “Big Trouble for Blast Barclay,” a Flash Gordon riff that echoes Moore’s “The Regrettable Ruse of Rocket Redglare,” and which even has the same artist, Mike White. All told, out of fifteen short pieces Morrison wrote for 2000 AD, around half have pronounced similarities with Moore’s work.

|

Figure 823: Although aspects of “Fruit and Veg”

owe a clear debt to Moore, the absurdity of the

Vegetable Liberation Front is pure Morrison.

(Written by Grant Morrison, art by Colin MacNeil,

from “Fruit and Veg” in 2000 AD #508, 1987) |

Certainly in light of facts like these it is easy to see why Alan Moore might have eventually concluded that Morrison was serially ripping him off. It is equally easy to construct a variety of defenses. Yes, Morrison uses ideas that resemble Moore’s. But, for instance, in “Fruitcake and Veg,” the Quinchian soliloquy comes in a story that also includes a group of armed revolutionaries who try to liberate vegetables from slavery and a monarchic potato. The story as a whole, in other words, is not a D.R. & Quinch knockoff in any meaningful sense, but rather one that uses one aspect of Moore’s D.R. & Quinch as a component of something different. (Of course, the evil vegetables bear no small resemblance to the plot of The Stars My Degradation…) And indeed, it’s worth recalling the degree to which the second D.R. & Quinch tale incorporated large swaths of the plot of The Utterly Monstrous, Mind-Roasting Summer of O.C. and Stiggs. The truth is that neither Moore nor Morrison have ever been shy about wearing their influences on their sleeves.

It’s also the case that Morrison often does very different things with the ideas than Moore does. This is perhaps clearest with “Big Trouble for Blast Barclay,” his Flash Gordon pastiche. As stated, there are obvious similarities to “The Regrettable Ruse of Rocket Redglare.” But there are also appreciable differences that give the stories genuinely different perspectives. Moore’s story is one of faded glory and nostalgia turned sour. The story is essentially a tragedy, its final twist serving as ironic justice to punish Redglare for succumbing to temptation. “Big Trouble for Blast Barclay,” on the other hand, has Barclay suffer an entirely undeserved fate at the hands of a purely malevolent foe. Redglare’s fate is a severe but intelligible consequence of his actions, whereas Barclay and his allies are brought down when a DHSS Snooper catches Barclay engaging in welfare fraud because he claims supplementary benefit, which requires he be available to work every day, whereas in reality he’s jetting off to the crab nebula. Barclay points out that “they don’t pay you to be a hero of the spaceways,” but to no avail, with a crowd of supporters rapidly turning on him and accusing him and his allies of “livin’ off the backs of the taxpayers” and of being “scroungers.”

|

Figure 824: Where Moore used Flash Gordon to satirize itself, Morrison

uses it as a vehicle to satirize Thatcher’s Britain. (Written by Grant

Morrison, art by Mike White, from “Big Trouble for Blast Barclay” in

2000 AD #516, 1987) |

It’s worth stressing the degree to which this is a fundamentally different approach. Moore adheres to the logic of Flash Gordon stories and pushes it to new places based on stretching its rules to a breaking point. Morrison, however, combines Flash Gordon with an extrinsic logic. The idea that the hero will eventually grow old and fat is not something Flash Gordon itself engages in, but it is still a sensible extension of the basic idea of the character. The idea that the Thatcher-era Department of Health and Social Security might show up and nick the hero for benefits fraud, on the other hand, is not something that is supposed to come up in a Flash Gordon story. Indeed, that’s the entire point – that it’s a completely absurd scenario for a Flash Gordon-style hero to end up in. And this absurdity is at the heart of the story’s unsubtle commentary upon Thatcher’s Britain, highlighting the cruelty of the crowd (who serve as the ones the end revelation – that the DHSS snooper is in fact an alien imposter who has been preparing the way for an invasion of evil alien hamsters – is meant to punish).

|

Figure 825: “Danger: Genius at Work,” while not derivative of Moore, is

also not exactly long on subtlety or nuance. (Written by Grant Morrison,

art by Steve Dillon, in 2000 AD #479, 1986) |

But perhaps the most important thing to point out is that while roughly half of Morrison’s Future Shocks have pronounced similarities to Moore’s, half don’t. Yes, Moore is self-evidently one of Morrison’s major influences, but it is equally self-evident that he is not the only influence. It’s not that all of these Moore-free stories are blindingly original ideas. “Danger: Genius at Work,” for instance, is a crashingly unsubtle dystopia about a world where “everyone looks the same, gets the same wages, lives in the same sort of house,” all in the name of total equality. (Indeed, in the story’s one solid gag, everyone is also given the same name: Terry.) Among the things forcibly equalized is intelligence, and the story follows the brilliant Theophilus Pritt as he is forcibly dumbed down to ordinary intelligence for coming up with too many clever inventions. It’s at once cliche and painfully self-indulgent, coming across as nothing so much as another writer whining about his under-appreciated brilliance.

|

Figure 826: The destruction of alien species in a tragic mismatch of scale,

a plot point Morrison took from Douglas Adams instead of Alan Moore.

(Written by Grant Morrison, art by Jeff Anderson, from “Return to Sender”

in 2000 AD Annual ’87, 1986) |

More successful, while still clearly derivative, is “Return to Sender,” an iteration of an oft-appearing subgenre of strips in which a beleaguered comics writer encounters fantastic obstacles in successfully completing and submitting his work. Morrison’s take on the material is endearingly gonzo, stuffed with an elaborate litany of ideas. They are, to be sure, not all his – two plot points (a race of very small aliens who are casually wiped out by contact with a comparatively giant human object and a human phrase that’s coincidentally a massively offensive insult in an alien tongue) are taken from the same sequence in Douglas Adams’s The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, for instance. But the story is still genuinely entertaining.

|

Figure 827: The humorously apocalyptic denouement of

“Curse Your Lucky Star.” (Written by Grant Morrison, art by

Barry Kitson, in 2000 AD #482, 1986) |

But there are also stories where Morrison excels with genuinely clever and well-executed ideas. “Curse Your Lucky Star,” for instance, is a solid story about a doomed effort to get rid of a man named Jeremy Chance who has freakishly good luck, but always at the expense of other people, resulting in an endless chain of catastrophes around him. It’s decided that the only thing to do is to put Chance into suspended animation and blast him off into space, but this only causes his luck powers to shift him billions of years into the past where he gets caught up in the formation of Halley’s Comet, which promptly smashes into the planet, killing everybody on Earth (except, of course, Jeremy Chance). It’s a classic Future Shock that mines some good gags out of its premise before wrapping it up in a finish that’s at once clever and inevitable.

|

Figure 828: John Hicklenton’s visionary weirdness elevated “The Invisible

Etchings of Salvador Dali” to greatness. (Written by Grant Morrison,

in 2000 AD #515, 1987) |

And then there is “The Invisible Etchings of Salvador Dali.” Of Morrison’s fifteen Future Shocks, it is both the strangest and the most visibly Morrisonesque. The story runs for three pages, with the first two focusing on the adventures of the unnamed narrator as he traverses a world of surrealist horrors to recover the eponymous etchings. Morrison is adept at coming up with compellingly weird images like a rain of narwhals or Albert Einstein with “a wheelbarrow full of clouds,” and artist John Hicklenton turns out to be just as creative, stuffing panels with a motley of bizarre and disturbing images, all realized in a brutal and viscerally grotesque style. The final page makes the unsurprising revelation that the narrator is in fact a mental patient, only to then reveal that the world has been reshaped by a “reality bomb” that has turned the world into exactly the same sort of surrealist landscape that the patient dreams of, and that the people at the hospital are preparing to wake him up in the hopes that he can cope with the world gone mad. Between the sly double twist and Hicklenton’s vividly visionary weirdness the strip numbers among the best of the Future Shocks, and makes it clear that Morrison has a vibrant creative vision of his own.

All the same, it’s undeniably the case that Morrison was following in Moore’s footsteps. Morrison makes no secret of the fact that his return to comics was inspired by Moore’s work on Marvelman and the aesthetic possibilities it offered. And while the British comics industry was not so large that there were a great variety of paths into it, it’s telling that Morrison largely recreated the specific path of Moore’s ascent while writing comics visibly in the same basic mould as Moore’s. But more than it reveals anything about Morrison’s creative faculties this simply reveals that fact that Morrison was a shrewd businessman. He saw that Moore was having more career success than any other writer in the history of the British comics industry and engineered a career that would give him the same success. As Morrison puts it, “to get work with Marvel UK and 2000 AD I suppressed my esoteric and surrealist tendencies and tried to imitate popular styles – in order to secure paying jobs in the comics mainstream. There is a reason those pieces were written in a vaguely Alan Moore-ish style and it’s because I was trying to sell to companies who thought Moore was the sine qua non of the bees knees and those stories were my take on what I figured they were looking for.”

|

Figure 829: Grant Morrison was given his

first ongoing 2000 AD strip, Zenith, far faster

than Moore had been given Skizz. |

But Morrison had more good fortune than just having an obvious figure to model his career on: his arrival on IPC’s radar coincided almost perfectly with Moore’s departure from the company. Which meant, in effect, that the job of being Alan Moore was, as far as 2000 AD was concerned, open. Accordingly, Morrison’s Future Shocks apprenticeship was markedly shorter than Moore’s. Where Moore spent two-and-a-half years and forty short stories earning the privilege of being asked to do a cheap rip-off of a popular sci-fi property, Morrison needed only fifteen shorts over a period of just under a year and a half before he was given an ongoing series. Indeed, in a fitting irony, Morrison was asked to do a superhero strip for 2000 AD, a direct reaction to the success that Moore was having in the US with Watchmen.

Which leaves little to do save moving on to that monolithic entity. It is in many ways difficult to conceptualize a magickal war in the traditional vocabulary of battles and victories, but there can surely be no effort to do so that does not conclude that Watchmen is the largest single conflagration. Certainly it marks the point where the drums of war give way to full-on combat. But the shape of that conflict is impossible to define, a fractal geometry where every act of precise measurement reveals nothing save for more measurements to take. This is, of course, the inevitable nature of a war that rages through what Moore will come to define as Ideaspace. A conventional, material war exists to be fought over defined territory – a physical geography that can be measured and bounded. But in Ideaspace, where any piece of terrain has an infinite number of adjacent points, the idea of a fixed and determined battlefield is wholly useless.

|

Figure 830: Blake transfigures the psychic

landscape of Albion based on his own vision.

(Copy G, Object 1, written 1793, printed 1795) |

This is, of course, the heart of what a magickal war is. When fighting for control over an endlessly shifting terrain, the construction of certainties, however fleeting, are the only weapons that make sense. This is, perhaps, what Moore ultimately meant when, in V for Vendetta, he spoke of ferociously defending that final inch of selfhood against a hostile world. Certainly it is what Blake meant when he proclaimed that he “must create a system or be enslaved by another mans.” And it is no surprise, then, that both Moore and Blake ultimately resorted to the same tactics in their respective Albionic Wars, abandoning all hope of defining the territory in which they fought in favor of radical and complete control over their definitions of themselves, ultimately transfiguring themselves into the very psychic landscape for which they battled.

And for Moore, Watchmen is the radiant blast of nuclear fire in which he is transformed from mere flesh into eternity. From the vantage point of history this seems inevitable, the precision engineering and meticulous craft of Watchmen pointing resolutely towards that outcome as though there was never any other possibility. It does not seem as though the particular world that Watchmen holds in microcosm, detonated within the particular psychic domain within Ideaspace in which it sits, at the particular historical moment at which it landed could ever have had any consequences other than the precise and exact ones that unfolded. It is as though Moore existed for this exact ascension, designed to be the exact piece of territory that he is.

|

Figure 831: Halo goes where people like her and Alan Moore always go:

out. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Ian Gibson, from The Ballad of Halo

Jones Book Three, in 2000 AD #466, 1986) |

And yet in setting this point as the one from which the narrative finally reaches Watchmen a strange truth emerges. Consider the end of Book Three of The Ballad of Halo Jones. After emerging from the Crush to find that the war has abruptly ended, Halo, still reeling from all that she’s seen and done, finds herself in what she knows to be an ill-advised affair with General Luiz Cannibal, her overall commander during the war, who in turn finds himself on trial for warcrimes. In the course of the trial, however, Halo discovers not only that Cannibal is guilty of the war crimes, but that a seemingly innocent action she took back on the Clara Pandy had made her an unwitting accomplice to his crimes – something that is all the more upsetting to her because it took place before she ever chose to involve herself in the war. It is a powerful moment that speaks to the way in which war implicates far more than just its ostensible combatants, a pressing concern in the wake of the Falklands and the sinking of the ARA General Belgrano. And so, after sabotaging Cannibal’s gravity suit just before he goes back out into the Crush one last time, thus dooming him, she steals his shuttle, and goes where she always goes and wants to go: out.

It is a strange irony that for all the inevitability of Watchmen and all its meticulous symbolism, Alan Moore himself clearly had no idea what he was doing. War was in most regards the last thing that Alan Moore wanted to be involved in. He was, after all, nothing more than a con man with a scheme to make himself and his friend Dave a quick buck by making some stuff up about superheroes. And yet he crafted the most devastatingly effective bomb imaginable and dropped it at an almost unimaginably perfect target. The result is that he is at once caught up in the blast, made irrevocably complicit in a decades-long chain of grueling conflicts, and liberated by it. He gets out, achieving both financial and creative independence for the rest of his life, and is trapped forever in the War’s gravity, crushed to nothing save an ugly smear of blood. And so as the War erupts with awful inevitability, the searing light of Watchmen bursts forth, and in the blinding deadly flash a single image becomes terribly and horribly clear: [continued]

July 10, 2015 @ 2:34 am

You tease…

July 10, 2015 @ 6:37 am

A man walking into a street, dropping his glasses and shooting a dog?

July 10, 2015 @ 11:46 am

Would you peg Morrison's recently-announced assumption of the head editorial position at Heavy Metal as being a similar attempt to "become the landscape," as such?

July 10, 2015 @ 11:47 am

Ha. It was actually something of a challenge getting this to connect to what I wanted as the first sentence of Book Two. And I was amused that the end result means that the first sentence of Book Two is actually part of the same sentence that ends Book One.

July 10, 2015 @ 5:48 pm

"But there are also stories where Morrison excels with genuinely clever and well-executed ideas. “Curse Your Lucky Star,” for instance, is a solid story about a doomed effort to get rid of a man named Jeremy Chance who has freakishly good luck, but always at the expense of other people, resulting in an endless chain of catastrophes around him"

This was the premise of a great X-Files episode. I'm not sure if it was written by Vince Gilligan, who quoted Watchmen at the climax of Breaking Bad…

July 10, 2015 @ 11:46 pm

Can I just say I've particularly enjoyed this brief foray into Morrison territory? I've picked up quite a bit of info about Moore from books, articles and DVDs, so while I always enjoy your perspective (con artist – brilliant!) you are going over quite a lot of ground I've seen before. There are some points reading LWiA where I'll think "hang on, hasn't he covered this already?", only to realise that I'm remembering Lance Parkin. Morrison, on the other hand, is pretty much a blank slate to me – I know some of his early DC work (Animal Man, Doom Patrol, The Invisibles), but virtually nothing outside of that other than what I've learned here.

Still, I shall bide my time and enjoy your take on Watchmen…

July 11, 2015 @ 12:50 am

There's going to be more Morrison in Book Two than you might expect.

More broadly, there's very much a Tone Shift about to happen. Book Two goes about things in a very different way. Still one that's unmistakably Last War in Albion, but nevertheless a very different sort of story to what has gone before.

July 11, 2015 @ 12:51 am

I think it's Morrison's greatest self-satire to date.

July 11, 2015 @ 8:31 am

I remember the idea of an individuals luck being detrimental to the health of those around them appearing in Ringworld by Larry Niven

July 12, 2015 @ 4:44 am

It's fascinating to note how the war is still going on, and has even kept developing since this project started. Often just subtly, but sometimes with obvious antagonism. Morrison's Pax Americana, from the DC Multiversity "event" seems the most pertinent in how he is dissecting Watchmen for what he believes works and doesn't. Does that him Stalin, reverse-engineering the Manhattan project?

July 13, 2015 @ 10:38 pm

Brilliant!

July 13, 2015 @ 10:40 pm

What was the Watchmen quote in the Breaking Bad climax?

July 13, 2015 @ 10:41 pm

Looking forwards to the next book and I have enjoyed the forays into Morrison's territory too as I am less well read on him than Moore.

July 13, 2015 @ 10:47 pm

It is odd, but when I think back to reading the Moore Future Shock's section of the War, I experienced a massive wave of nostalgia as I was seeing the stories again for the first time in decades – that was so sweet. But somehow I can't recall in the same way Morrison's Future Shocks, and that surprises me. I do vividly remember Zenith which I loved deeply as a story – it could be the case that I dropped out of reading 2000AD for a while, but I'd have no way of knowing unless I dig out the originals from my parent's attic.

So I am finding the whole war an interesting exercise in memory and nostalgia too, and it is really interesting to come across things I was sure I had read that I haven't.

"But the shape of that conflict is impossible to define, a fractal geometry where every act of precise measurement reveals nothing save for more measurements to take. This is, of course, the inevitable nature of a war that rages through what Moore will come to define as Ideaspace."

This whole paragraph is beautiful.

July 15, 2015 @ 8:44 am

I'm also very much looking forward to Vol. 2 whose serialization will be our companion for the next two years! ("The coverage of Watchmen will be as large as the coverage of everything before it", as https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/2027287602/the-last-war-in-albion-and-other-tales/description says.) And because The Last War will be continued at least to Vol. 6 — the funding of Vol. 7 is almost a certainty, I think — it is already close to a ten-year project. Let's all admire Phil's enthusiasm and stamina 🙂

July 15, 2015 @ 9:00 am

/weeps

July 15, 2015 @ 11:24 pm

Your'e a hero Phil.

July 15, 2015 @ 11:29 pm

I visited my parents yesterday and grabbed out of my large stash in their attic a bunch of comics I'd not seen for years! So I managed to find my original copies of Near Myths, A1, Centrifugal Bumble-Puppy, Swamp Thing, Hellblazer, including tons more and even an interesting interview with Moore post-Watchmen in the Comics Journal and one nice thing by Moore (in a collected edition) with Eddie Campbell called (I think) Tourism for Agoraphobics.

I'm looking forwards to a massive binge-nostalgia read and all inspired by this blog – really looking forwards to the Watchmen section (found that too).