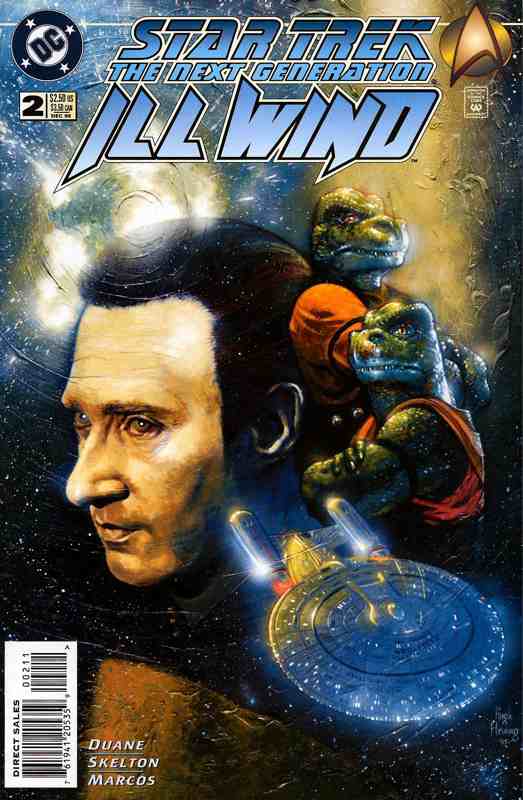

Myriad Universes: Ill Wind Part Two

The racers are on their marks at the starting line. Captain Picard has Data call up the course schematics onscreen. It’s a winding, zigzagging course around the star that will take the racers about three days to traverse, a quick pace for a solar sail vessel. But, as Captain Picard says, “These are the best”. When Commander Riker asks him if he’d rather be “out there”, Jean-Luc replies that he already is. The Enterprise crew wishes all the competitors good luck in turn, but when they get to the Cynosure team, Deanna observes that they’re without their sail technician. Will comments that the Kihin navigator must not have found him “to her taste”, to which Deanna replies “On the contrary…She found him very tasty indeed”. Meanwhile the Thubanir captain is still alive, though Deanna quips that it’s still early yet.

The racers are on their marks at the starting line. Captain Picard has Data call up the course schematics onscreen. It’s a winding, zigzagging course around the star that will take the racers about three days to traverse, a quick pace for a solar sail vessel. But, as Captain Picard says, “These are the best”. When Commander Riker asks him if he’d rather be “out there”, Jean-Luc replies that he already is. The Enterprise crew wishes all the competitors good luck in turn, but when they get to the Cynosure team, Deanna observes that they’re without their sail technician. Will comments that the Kihin navigator must not have found him “to her taste”, to which Deanna replies “On the contrary…She found him very tasty indeed”. Meanwhile the Thubanir captain is still alive, though Deanna quips that it’s still early yet.

After the pre-race formalities, the Alkamin captain informs the Enterprise crew that they’ve seen something unusual on the keel of the Scherdat crew’s yacht. Captain Picard asks the Scherdat if they’ve modified their ship in any way, but the Scherdat captain responds in the negative. Worf scans the ship and finds something that doesn’t fit official speculations, but he can’t get a transporter lock on it, so the Enterprise is forced to movie into the race zone and use a minimal power tractor beam to remove it. They manage to remove the device and get it off the course just in time, as it turns out to be an explosive that promptly detonates, thankfully harmlessly out of range of any of the ships. The Carrighae captain complains about the Enterprise forcing a false start, but Captain Picard cuts him off and he and Deanna cynically note that moving their ship into the race field, thus endangering the lives of the competitors, was precisely what the Carrighae captain had tried to bribe Captain Picard to do in the first place. While the competitors prepare for a restart that will take a hour or two, Captain Picard wants his crew to investigate where this bomb might have come from and how it got on the Scherdat ship. Jean-Luc decides “This sport is definitely not what it used to be”.

Six hours later, the race has successfully restarted. Captain Picard asks Worf and Will how things are going, and they say things are fine except that the Mestral’s tender, which she had previously sent away, has not yet arrived at Capella, where it was meant to undergo servicing. Since that’s only a half-day away, the crew is supicious something might have happened to it, so Captain Picard has Worf inform Starfleet Command while he goes inform the Mestral. The Mestral says she’ll see what she can do, but doesn’t see any reason to withdraw from the race, despite Captain Picard’s growing concern. Following a quick exchange where she accuses him of worrying too much while he accuses her of not worrying enough, Mestral gives an impassioned speech about living a life of choice. She asks the Captain how many “little things” he’s had to give up in service to duty and security, but he responds that we all make sacrifices if it means service to a good cause. The Mestral, however, draws a line between “service” and “slavery” and outright says she’s “an example of one of the few kinds that hasn’t been outlawed”.

As the absolute ruler of two billion people, Captain Picard understandably views this claim with some suspicion. But she argues that as rule is passed through a hereditary system she never asked for this job, she’s given her people and her world almost all of her life and her time and is determined “to keep just a little something” for herself. For her solar sailing, and being one with the elements, is a great equalizer, because nature doesn’t care about status or importance or everyday affairs. And as this is the only thing that keeps her going, she refuses to let anyone or anything take it from her. Captain Picard understands, although he wishes he could say he approves as well, and he and the Mestral must agree to disagree. As they sign off, Data calls the captain with news that the star is behaving somewhat unusually: Although GC 2006 is known for its irregular behaviour, it’s currently radiating light and heat at a rate much greater than usual. Data is quick to point out that this could be perfectly normal behaviour for the star, as it’s never been studied in particularly extensive detail, but Captain Picard wants to be kept updated, as he’d rather shut the race down if it looks like it will start to get too dangerous.

Later, Captain Picard is chatting with Commander Riker in ten-forward, explaining the new crystalline masts that The Mestral seems to hate so much. They are joined by Deanna Troi, who says she’s been feeling inexplicably sleepy (not “tired”, but “sleepy” and Doctor Crusher can’t seem to find out why), and just wants them to know she may not be performing at full capacity. Meanwhile, the Sauch and Lorherrin are up to their old tricks again. The Sauch ship has placed itself between the Lorherrin ship and the Sun, effectively stealing their light. This isn’t illegal but it is, as they used to say, something of a Dick Move. The Lorherrin are pissed, doubly so that it was the Sauch that did this, and respond by jettisoning a mooring cluster behind them, such that it will be on a trajectory to tear the wing of the Sauch craft. The Sauch are unconcerned though, convinced their sails are untearable, as demonstrated by the sail promptly tearing from impact with the debris.

On the Enterprise, Worf notes that the damaged Sauch ship is now on a collision course with, ironically enough, the Lorherrin yacht. He asks if he should activate a tractor beam to grab the drifting craft, but Captain Picard says that “under no circumstances” should they do such a thing. He explains that it’s one thing to remove a bomb before the race begins, but interfering with the natural outcome of the race itself would cause an interplanetary incident. “While I dislike seeing any creature die from its own stupidity,” Captain Picard says, “This sort of thing is just part of the risk”. The Enterprise crew’s hands are forced, however, when the careening ship’s trajectory changes and begins moving to the Mestral’s ship. Captain Picard hails the ship, but the Mestral is already aware of the situation and has moved to react. She must act fast though, as avoiding disaster requires an impossibly deft and complex bit of evasive manoeuvreing, which she manages to pull off. “Maybe a few seconds’ utter terror will teach them to be a little less reckless in the future. Then again, maybe the Moon will fall down,” she says.

The Enterprise crew now has to contact the Sauch and Lorherrin to see if they’re alright, and while nobody’s particularly inclined to worry too much about either of them anymore, they do have a duty to perform. Furthermore, there’s still the matter of the bomb that caused the false start: Captain Picard and Data find it interesting that the closest ship to the Sauch and Lorherrin right before all that unpleasantness was the Carrighae one. On the Mestral’s yacht, the ruler confesses to her consort Rav that she feels terrible she’s become such a burden to Captain Picard, as she admires the strength of his convictions and his masterful ability to command. Rav’s heart breaks for her, because he knows how much she was hurt by having to give up her name and individual life to become Mestral. But, echoing the words of Captain Picard, she says she serves a higher calling, and she must serve as an example of the way she hopes her people will live. He urges her to change the law so that someone else can succeed her sooner, but she refuses, asking how would it look if she changed a law for her own personal interest. It would be a betrayal of every oath she took, including the one to marry him. A betrayal of that level would be a betrayal of herself, her people and of Rav, and that’s truly something she cannot do.

Perhaps the thing that strikes on the most about Ill Wind, even down to its title, is how cynical it is. And I mean *those exact words*. The common statement among Star Trek: The Next Generation defenders (as opposed to Dominion War fans who try to spin “redemptive” readings of Star Trek: The Next Generation) is that it was “idealistic”, “optimistic” and “hopeful”, in contrast to the grimdark edgelord pessimism they see in later science fiction series. This has a grain of truth about it, but the reality, as reality is, tends to be more complicated. Gene Roddenberry certainly wanted it to be idealistic and conflict-free, but this rankled just about every writer who worked on the show because they couldn’t conceptualize of narrative without conflict, because they couldn’t conceptualize of narrative without Aristotelean drama.

As such, there were plenty of Star Trek: The Next Generation stories in the post-Roddenberry years that were cynical in the Dominion War/Battlestar Galactica way (no surprise they were penned by the same people who went on to helm those shows): Just take a look at “The Most Toys”, “Reunion”, “Ethics”, “I, Borg” “The Pegasus” or “Preemptive Strike”. Or, you know, don’t. But while Star Trek: The Next Generation has been no stranger to cynicism, the difference this time with Ill Wind is in the *way* it’s being cynical. The Dominion War/BSG style of cynicism tends to involve a lot of shock-value betrayals, deaths, and fetishistic fascination with “how far” a character can be “pushed” while still remaining “moral” (and indeed calling into question notions of morals and ethics in general). What Diane Duane is doing in Ill Wind is different: A classic Star Trek: The Next Generation trick, the violent rivalries and shocking twists and betrayals are all happening outside of the Enterprise, but unlike the common refrain from critics of this series, the crew doesn’t sail in and wag their fingers either.

Far from it, the Enterprise crew are, thanks to both diegetic and extradiegetic reasons, kept at arm’s length from interfering in any way. All they can do is sit back and watch and do what they can to keep a merely hopeless and unpleasant situation from snowballing into an actual catastrophe. But there’s no judgment passed here either: While we’re obviously meant to sympathize with Captain Picard and the rest of the crew, they can’t even be be bothered to muster up any energy to be righteously indignant anymore, let alone be compelled to try and fix things. The Enterprise seems brokenhearted and sad, but perhaps more than anything else tired. Deanna, the empathic heart of the ship, even straight-up says she’s getting drowsy. This is not their fight, and if everyone out there doesn’t want to listen to what they have to say anymore, then so be it. The long cosmic dark awaits.

Apart from that, we get further development on the character studies that will increasingly become the bulk of Ill Wind. While it was set up last issue, now Captain Picard and the Mestral are explicitly being paralleled as people of duty, honour and loyalty whose service to those ideals has pulled them in different directions. Duane does something clever here, because the narrative roles Captain Picard and the Mestral play here are the same that, in other series, would be filled by love interests. But they’re very explicitly not, a sign Duane understands that Star Trek: The Next Generation‘s maturity precludes the need to throw some stock titillation and shipping bait at its readers every story. And furthermore, the Mestral’s “burden of the crown” speechifying is obviously meant to be taken with a serious grain of salt, honourable and loyal as she may be in other areas (Starfleet doesn’t want Captain Picard to sail either, but he’s OK with it, and he’s not even absolute ruler of two billion people), a tacit setup for the direction her character arc will go in future issues. One last time, the character development goes to the guest stars, but it’s not our responsibility to make them learn their own lessons.

But perhaps that famed optimism is still here. Deanna’s only sleepy, not tired, as she stresses to us. And when Commander Riker asks Captain Picard if he wishes he was “out there with them all”, Jean-Luc says that he is.